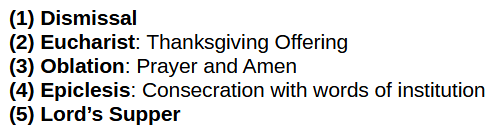

The original liturgy:

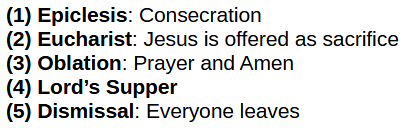

The Roman liturgy:

Summary

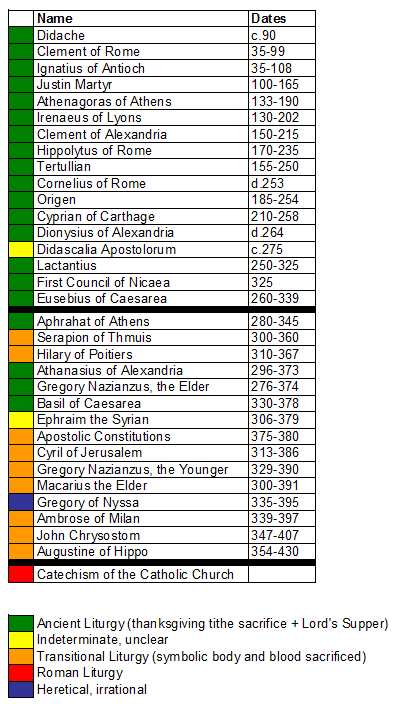

The chart above summarizes what we’ve found throughout this series.

First, the ancient liturgy…

- Dismissal

- Eucharist

- Oblation

- Epiclesis

- Lord’s Supper

…is strongly attested to. Sixteen out of seventeen writers that we examined in the first 300 years affirmatively assert an ancient, non-Roman liturgy. They don’t always discuss all aspects of that liturgy, but when they do discuss it, it is always the same elements in the same order. The evidence is overwhelmingly against the medieval Roman liturgy:

- Epiclesis

- Eucharist

- Oblation

- Lord’s Supper

- Dismissal

In summary:

None of the early sources we examined contain a Roman liturgy.

One out of those seventeen writers (e.g. the Didascalia Apostolorum) is more complicated. It is widely accepted to be a heretical and non-influential document, and so does not strictly count as a church source at all, but we consider it nonetheless. It does not overtly and explicitly oppose the ancient liturgy, although it certainly appears compatible with it in places. But it also alludes to the developments found in its “successor” (the Apostolic Constitutions) written a century later. The document may have been a work of heresy that began as a corruption of the ancient liturgy and slowly morphed into the heretical movement found in the late 4th century, but this is mostly speculation.

Second, the transition period of the following century (e.g. from ~330AD to ~430AD) shows a clear trend of doctrinal development. The four writers who described the ancient liturgy in their writings all died early in the period (before the rise of Roman Catholicism in the 380s, as discussed in Part 17: Interlude). Nine of the fifteen writers in this period showed doctrinal development to varying degrees that can roughly be described as follows:

The bread and wine symbolize Christ’s body and blood.

The thanksgiving—eucharist—is a sacrifice of his body and blood.

The sacrifice is propitiatory, for the remission of sin.

This is still not a Roman liturgy, in large part because Transubstantiation and the Real Presence are denied.

Citation: Wikipedia, “Real presence of Christ in the Eucharist.”

On the other hand, these changes are strongly associated with the introduction of the sacramental theology that would one day develop into the Roman Catholic system of seven sacraments defined at the Council of Trent in the 16th century.

There are two outliers. The first is the poet Ephraim the Syrian. His work is, in my opinion, too full of ambiguous figurative language to make any strict conclusions on his theological views. The other is Gregory of Nyssa, who is at times ancient, heretic, and Roman liturgists all mixed together. His views are extreme, strange, and unique. It is difficult to categorize them with any form of orthodoxy, whether ancient or modern. Judge him how you will.

Having evaluated the evidence, let’s look at our opening thesis:

With the slight caveat that the Didascalia Apostolorum is unclear (for a number of reasons), our thesis has been proven correct.[1] It’s not particularly ambiguous.

We’ve also confirmed what the Catholic Encyclopedia said:

Citation: Adrian Fortescue, “The Origin of the Mass.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol 9. (1910)

In particular, we found that the ancient liturgy was first found in its complete form in Justin Martyr. That liturgy was maintained until approximately 350AD, when changes started rapidly occurring. Thus we note that the period from the middle of the 4th century until the 6th or 7th century represented a two or three century time of transition and doctrinal development when the Roman liturgy arose from out of the newly risen Roman Catholic Church.

While this is certainly the case since the late 4th century, we do not find this to be a credible claim prior to 350AD. In a number of the interludes and articles in this series—especially Part 27: Interlude—we examined FishEaters article “The Eucharist” and didn’t find any reason to question our thesis. Bardelys’ comment appears to be an instance of the so-called Kauffman’s Law:

We examined this in Part 32: Interlude.

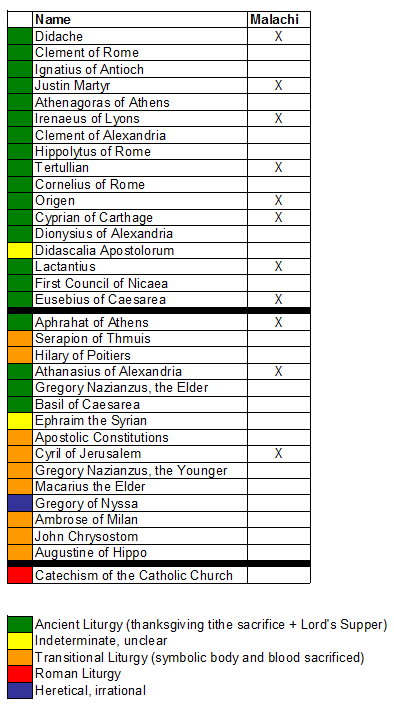

Malachi

One of the key themes of this series was that of Malachi’s prophecy:

In FishEaters article “The Eucharist,” she suggested that the incense and pure offerings of Malachi referred to the both Christ and the church offering Christ’s literal body and blood to the Father. These are supposed to be a replacement for the defective sacrifices previously offered:

But this view is not supported by our examination.[2]

Many times throughout this series—The Didache, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus (see Part 6 and Part 36), Tertullian, Origen, Cyprian, Aphrahat, Athanasius, Eusebius, Lactantius, Cyril—we noted that the ancient church viewed the thanksgiving—eucharist—as the sacrificial fulfillment of Malachi 1:11. Over nearly 400 years, eleven out of the thirty-two writers we examined (a full third!) explicitly confirmed this view.

Out of the whole Bible that could have been referenced to discuss the Eucharist, a third chose to discuss Malachi’s prophecy directly, and they uniformly did so to support the ancient, non-Roman conclusion. This is a remarkable testimony. Meanwhile, in that same period, we didn’t see any writer offering Christ’s body up as a fulfillment of Malachi.

Of these eleven, Cyril is especially notable because he believed that the church offered Christ’s (symbolic) body and blood as a propitiatory sacrifice, and yet when he discussed Malachi’s prophecy, he said it was fulfilled in the blessings, praise, and glorification of God made by the congregation. Though it is alllegedly claimed that he espoused an orthodox Roman Catholic belief, he nevertheless made no mention of the Mass Sacrifice. He utterly failed to support the Roman liturgy, and instead merely confirmed the ancient belief.

Meanwhile, we found that Malachi’s prophecy was cross referenced and supported in various ways, often by multiple writers. Many of the other writers who didn’t cite Malachi directly still cited the same cross referenced verses that those who cited Malachi did, thus coming to the same conclusion anyway. These passages include:[3]

One writer—Origen—even cited John 6 in this context. Faced with the choice to then cite the Lord’s Supper as the fulfillment of John 6, he not only failed to do so, but identified the food of Christ with the Word of God.

When Augustine, who described offering Christ’s body as a (symbolic) sacrifice, also cited John 6. He had the perfect opportunity to cite the Lord’s Supper. Well, it turns out, he did, but only to clarify that the blood and body were to be understood spiritually. Rather than importing the Lord’s Supper into his understanding of John 6, Augustine imported John 6 into the Lord’s Supper, thus concluding that the body and blood of Christ at the Lord’s Supper were spiritual, not physical. Roman Catholics don’t do it this way! Augustine went out of his way to call the Lord’s Supper a “resemblance” (figure) of the real events completed in the past.

Cyril, who also offered Christ’s body as a (symbolic) sacrifice, also read John 6 and concluded that Jesus was speaking of the spiritual and scoffed at the very notion that Jesus was inviting them to eat his literal flesh!

When Clement of Alexandria cited John 6, he concluded that the flesh figuratively represents the Holy Spirit.

Time after time, the early writers failed to comprehend that they were supposed to be describing a Roman liturgy!

Citation: Adrian Fortescue, “The Origin of the Mass.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol 9. (1910)

Chief difficulties indeed! The early writers simply refused to describe the medieval Roman liturgy that the Roman Catholic church was supposed to have received from the Apostles themselves.

The testimony of scripture was overwhelmingly clear to these writers. Even as they fell into doctrinal error, they still maintained the essential meaning of Malachi’s prophecy. Imagine the Roman Catholic here:

“We offer Christ’s body as sacrifice for our sins…”

Yes! Yes!

“…and now we read the prophecy here in Malachi 1:11…”

Yes! Tell those Protestants about how Christ fulfills it!

“…that the Church of Christ offers sacrifices of blessing, praise, and glory to God.”

Wait! No! That’s not right!

On Doctrinal Development

One of the other major themes of this series is the examination of precisely how the religious and political events impacted doctrine, which changed through a series of stages. We illustrated these examples with the Ouroboros:

Roman Catholicism relies heavily on circular reasoning, in large part because its formation is based on eating its own tail. Some Roman Catholic apologists have termed this spiral reasoning, where doctrine builds and improves upon previous doctrines in an uninterrupted chain. But, as we’ve seen throughout this series, the Roman liturgy is based on intermediate developments from the ancient liturgy. These, often influential, intermediate developments were based on heretical and/or forged documents.[4] Many of the intermediate developments are now explicitly anathematized. The “spiral” development of doctrine through heresy just produces heresy.

For example, in order to arrive at the literal substance of the crucified body of Christ in the appearance of bread being offered as a propitiatory sacrificial re-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice (yeah, that’s a mouthful), the doctrine had to go through stages of development, including:

- Bread is sacrificed to God

- The bread was, in nature, both bread and body simultaneously

- The body of Christ was symbolic and spiritual

- The body of Christ was daily re-sacrificed

- The dead and buried body of Christ was offered as food at the Last Supper

The Roman Catholic denies all of these things, and yet the Roman Catholic doctrines all derive from these, rather than directly from the ancient liturgy. Its own Saints believed these things at various points. The Roman Catholic Church had to eat its own tail in order to arrive at what it now believes.

The doctrine of Transubstantiation, for example, had to be created because the intermediate doctrine had the worshipers worshiping bread, a clear instance of idolatry. But, of course, transubstantiation isn’t actually real—it isn’t apostolic and the early church denied it—so worshipers are still worshiping bread, only now they are lying to themselves about it.

But, and this is key, Roman Catholicism doesn’t believe any of its doctrines were corrected from error. All of them are asserted to be apostolic for the whole existence of the Church. Any differences are presumed to be superficial (i.e. in appearance only and not in substance). It cannot actually admit that it had intermediate doctrines that were heretical, even though this is obvious from the historical record. So, it just imagines—by authority alone; without any rational justification—that all existing historical evidence supports its modern view:

“We have always been at war with Eastasia.”

Err, I mean,

“The church always believed in Transubstantiation.”

Sacraments and Mysteries

Another other key theme of this series was the discussion of the sacraments and mysteries in Part 9: Tertullian, Part 27: Interlude, Part 31: Ambrose, and Part 34: Hilary. Earlier, this was also discussed in “Sanctified Marriage, Part 6,” “Why is the Sacrament of Marriage Important?,” and “Sacraments are the Reason for the Priesthood.”

In ancient Rome, in the centuries before Christ, the sacramentum was a sacred legal oath taken before the gods.

In the first century, Paul wrote of the mysteries—previously hidden sacred secrets—now having been revealed to us about the gospel—good news—of Christ and his saving work of grace through faith. He mentions nothing of sacraments, only separately describing various practices that Christians perform (e.g. baptism, thanksgiving, Lord’s Supper, prayer, helping the poor, etc.)

In the second century, Apuleius—a Latin Platonist philosopher—gives sacramentum the meaning of “religious initiation rite.” Presumably this is because the Roman sacramentum—the sacred oath of service taken before the gods by a soldier before he was initiated into military service—was both a legal and a religious rite.

In the third century, the Roman sacramentum was no longer an initiation rite, but was an oath sworn in a yearly ritual.

Between the late-second and early-third centuries, Tertullian would borrow Apuleius’ usage when he described the Christian practices of baptism and thanksgiving as sacramentum, religious initiation rites and pledges to God. Tertullian would also describe pagan initiation rites as mysteries, but he wouldn’t explicitly conflate his notions of Christian sacraments and Pagan mysteries with Paul’s mysteries.

Between the late-third and early-fourth centuries, Lactantius would explicitly call the repeated Christian rituals sacraments. In this, he reflected the change to the word that was reflected in the Roman legal sense.

In the fourth century, the mysteries would lose both the idea of being sacred secrets and of being initiation rites. They would take on the purely ritualistic sense that sacramentum had. This meant that the mysteries went from being sacred knowledge—gained by initiates—into being mysteries—repeated rites—that all members experienced without full understanding.

In the late-fourth century, Basil, Gregory of Nyssa, Ambrose, Hilary, and John Chrysostom would all conflate the sacraments and the mysteries in their writings and began to associate the mysteries—referring to the salvific grace of Christ—with the Christian rituals—as sacraments. Jerome would create the Latin Vulgate, the official Bible of the Roman Catholic church. In doing so, he would explicitly translate Paul’s Greek mystery into the Latin sacrament, thus officially importing the developed ritualistic concepts described above into the saving work of Christ through grace by faith.[5]

This conflation formed the theological basis for the development of the Roman Catholic systems of sacraments and salvific graces, and is the basis for the thanksgiving—eucharist—becoming a propitiatory sacrifice of Christ’s body for the remission of sin. This change also formed the theological foundation for a separate celibate priesthood to administer them in the newly risen Roman Catholic Church.

The conflation of mystery and sacrament turned the saving work of God by grace into ritual observances. It is the origin of Roman Catholic sacramental system of works-righteousness. The Eucharist became a rite by which grace—in the form of a propitiatory sacrifice for the remission of sin—was dispensed.

This conflation not only permitted the corruptions of the thanksgiving sacrifice—eucharist—and the Lord’s Supper, but it hid even the very definition of faith…

Citation: “Hebrews 11:1 Commentary.” REV Bible

…and what it meant to be saved. For this reason, my next series will discuss justification by faith, for the Roman Catholic sacramental system of salvific graces is why Roman Catholics and non-Roman Catholics teach a fundamentally different gospel.

The Roman Catholic Apologist

Another theme we discussed was that of the Roman Catholic Apologist. In Part 27: Interlude, we discussed FishEaters’ article on the Eucharist. In Part 32: Interlude we discussed the apologist Church Fathers’ article on the Sacrifice of the Mass.

But, now that you’ve read the whole series, you can go get a balanced perspective by reading what a more serious apologist has to say. Joshua Charles—one of the more prominent Roman Catholic apologists on the internet today—has written about the Eucharist in three articles:

Becoming Catholic #1:

The Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist in the Church Fathers

Becoming Catholic #9:

The Church Fathers, and the Christian Sacrifice of the Eucharist

Becoming Catholic #13:

St. Justin Martyr, the Mass, and the Church’s Early Eucharistic Doctrine

Do you now know enough to evaluate such attempts on your own?

Charles cites The Didache, Ignatius, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus (see Part 6 and Part 36), Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, Hippolytus, Origen, Cyprian, the Council of Nicaea, Alphrahat, and Ambrose all supposedly supporting the Roman liturgy.

Recall that we concluded that the Roman liturgy is not found in any of them. Not a single one sacrificed consecrated bread—Christ’s body—in the thanksgiving. It isn’t possible that we are both right, unless each church father badly contradicted himself (which would invalidate Roman Catholicism anyway). Did Charles find, in these twelve sources, a liturgy that even the Catholic Encyclopedia admits is not there? Charles didn’t merely find one source that disagrees with the Catholic Encyclopedia, but twelve sources. As with apologists FishEaters and Church Fathers, this claim is dubious. Honest historians do not make these kinds of claims.

Charles also cites Serapion, Cyril, Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory Nazianzen the Younger, John Chrysostom, and Augustine, which we also cite.

Compare our citations and see what you think about it. Do you think that Joshua Charles will note that most of these men sacrificed the symbolic body and blood of Christ in the thanksgiving, a viewpoint that isn’t compatible with the Roman liturgy? Will he make these citations by assuming that they directly describe liturgical elements fully compatible with the Roman liturgy?

Conclusion

At the start of this series, I said:

While I’ve satisfied the terms of my opening claim, we still need to hear from others. Perhaps this series itself has sent everyone running. Or perhaps others have just been waiting for the end to weigh in. I do not know. I did not write this series to gain readers. I wrote it to, maybe, one day help a single person. If I lose reach, influence, and clicks as a result, who am I to complain?

It’s always a challenge to write something like this, because it is ultimately one-sided. Without someone to provide constructive feedback or even a rebuttal—in whole or in part—it is impossible to know how much of what I write is subject to critical bias. While virtually all of FishEaters quotations are given in a restricted context, certainly some of my quotations—while more encompassing—must also have insufficient context. There is simply no way that I wrote a series of this magnitude without committing errors of my own. Even in the process of writing this series, I had to go back and edit already published articles to fix this or that. I will no doubt have to do so again.

And so, I humbly ask that, if anyone has anything they’d like to share, please do so in the comment section.

Also, thanks for reading.

Footnotes

[1] The caveat of Survivorship Bias also applies, but doesn’t alter the conclusion. We can only determine what the writers that we possess wrote. We can’t easily know what people who didn’t write believed or know what writings on the subject may have been lost. Moreover, the writings we do possess may be corrupted.

[2] Notably, the new offering “from the rising of the sun even to its setting” and “in every place” is not fulfilled in offering Christ’s body and blood only during the scheduled Lord’s Supper during Roman Catholic Mass (mostly) in Roman Catholic churches.

[3] Epistle of Barnabas, Chapter 2, speaks of Psalms 51:17.

[4] The forgeries Didascalia Apostolorum, Apostolic Constitution, the Gnostic Protoevangelium of James, Donation of Constantine, and the False Decretals were all used in the development of church law and other innovations of doctrine and practice. Their rejection as forgeries did not involve rolling back the changes that the forgeries helped to enact.

[5] Besides the conflation of mysterium and sacramentum, the Latin Vulgate also corrupted Genesis 3:15 (“she” rather than “he”; led to the Marian dogmas), Psalms 98:5 (“adore his footstool”; led to Eucharistic Adoration), and altering the nature of salvation by translating “repentance” as “penance” (Matthew 3:2, 4:17; Mark 6:12; Luke 13:3,5, 16:30, 17:30; Acts 2:38, 8:22, 26:20) and “declared righteous” as “made righteous.”

Pingback: The Living Voice

Pingback: Justification by Faith, Part 1

Pingback: Sacraments, Part 3: Baptismal Regeneration - Derek L. Ramsey