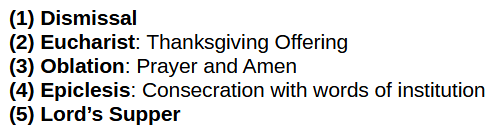

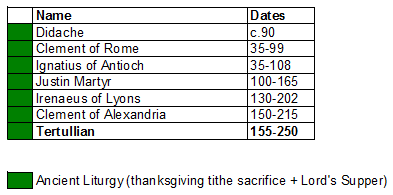

The original liturgy:

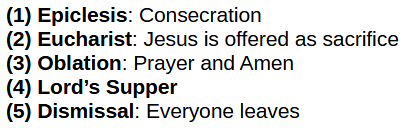

The Roman liturgy:

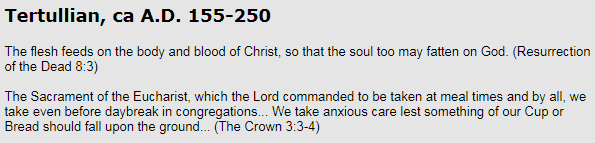

Tertullian

At first glace these quotes seem rather tame and innocent. But they are among the most divisive words ever written in the church. For the first time in this series, additional contextual analysis—from outside this mostly self-contained series—is required. Tertullian is the first writer in the church to use the word “sacrament.” A discussion of the sacraments is a massive topic and would be a huge undertaking in-and-of-itself. Rather than do that here, I ask that you read “Sacraments are the Reason for the Priesthood” before reading this article, but I will try to summarize here.

Tertullian called pagan rituals “mysteries” and Christian rituals “sacraments” and drew parallels—not equality—between them. The Bible uses the term “mystery” to refer to the saving work of God. It does not use the word “sacrament” (meaning sacred vow or pledge) or “mystery” with respect to any of the seven Roman Catholic sacraments. In the late 4th-century, Jerome would explicitly conflate these two words and help usher in the Roman Catholic system of sacraments. Tertullian himself never drew this conclusion, but that conclusion is credited to him. However, as we’ll see below, Tertullian also seemed to be arguing a type of works righteousness / justification-by-works that Roman Catholicism would embrace, so his words cannot be dismissed.

But Tertullian was no Roman Catholic. He identified just two sacred Christian rituals (what he called “sacraments” or pledges to God): baptism and the Lord’s Supper. Whether he was correct to view these rituals as vows or pledges to God, his view of the sacraments was decidedly different than that of the Roman Catholic conception.

Though the Eucharist is a Roman Catholic sacrament, it is beyond the scope of this series—which is focused on the liturgy itself—to explain why calling the Eucharist a sacrament is fundamentally flawed. Hopefully this brief explanation and the linked article are enough information.

Now, let’s proceed to the first quotation. As we often do, we bring in some more context:

Citation: Tertullian, “On the Resurrection of the Flesh.” Chapter 8

As in the selected quotation that FishEaters used, one can see how Tertullian pairs a physical and spiritual act together.

flesh is washed; soul is cleansed

flesh is anointed; soul is consecrated

flesh is signed (with the cross); soul is fortified

flesh is shadowed with the imposition of hands; soul is illuminated by the Spirit

flesh feeds on body and blood of Christ; soul is fattened on its God

It is tempting to think this is a matter of cause-and-effect, that the acts of the spiritual are an effect of the physical acts, and Roman Catholics definitely do take this viewpoint. But the reason we looked at the full context is because at the very beginning, Tertullian tells us what the context is:

Tertullian opens by saying that belief procures salvation. Physical acts did not cause spiritual change. The Christian who believes while in the flesh procures salvation and, as a consequence—not cause—of that salvation, does service to God (e.g. laying on of hands) and receives spiritual effects. Every physical and spiritual effect Tertullian describes is due to a service one performs as a consequence of having already procured salvation through belief. The thrust of Tertullian’s argument is that one can’t be dead to receive transformative spiritual effects. Salvation, belief, and the physical and spiritual acts of a believer must take place while one is alive. Once a person dies, it is too late to impact the soul (sorry, Purgatory, you can’t suffer for the temporal punishments of sin for atonement after you die).

But what about the more basic question of whether or not the flesh and blood of Christ are figurative or literal? The language appears to be quite metaphorical (e.,g. “shadowed” vs “illuminated”), but let’s verify this by examining Tertullian’s figurative language elsewhere in the document. For example:

Citation: Tertullian, “On the Resurrection of the Flesh.” Chapter 63

As with many other patristic writers, Christ’s flesh and blood are his doctrine: the Word of God. When you eat and drink, you consume the resurrection of the flesh (that is, eternal life). This is as Jesus said in John 6 when he referenced the metaphor in Isaiah 55. Tertullian joins the long line of others who interpret the body and blood of Christ figuratively.

But in case even this is not 100% clear, we need only look elsewhere:

Citation: Tertullian, “To The Trallians“, Chapter 8

The body of Christ is faith and the blood of Christ is love. And there is more:

Citation: Tertullian of Carthage. “Against Marcion, Book 4.” §40

This is beyond-a-doubt explicitly figurative.

Now we can see, as we discussed in the Part 8: Interlude, that Tertullian joins the others in understanding Malachi to be talking about what the true sacrifice of the church is:

So that with this agrees also the prophecy of Malachi:

— such as the ascription of glory, and blessing, and praise, and hymns. Now, inasmuch as all these things are also found among you, and the sign upon the forehead, and the sacraments of the church, and the offerings of the pure sacrifice, you ought now to burst forth, and declare that the Spirit of the Creator prophesied of your Christ.

Citation: Tertullian of Carthage. “Against Marcion, Book 3.” §22

— meaning simple prayer from a pure conscience…

Citation: Tertullian of Carthage. “Against Marcion, Book 4.” §1

— one, no doubt, whereby He would testify that He was not destroying the law, but fulfilling it; whereby, too, He would testify that it was He Himself who was foretold as about to undertake their sicknesses and infirmities. This very consistent and becoming explanation of the testimony, that adulator of his own Christ, Marcion seeks to exclude under the cover of mercy and gentleness.

Citation: Tertullian of Carthage. “Against Marcion, Book 4.” §9

Tertullian speaks of Eucharist, but it is not the Eucharist of the Roman liturgy. It is (1) only from those of a pure heart who can (2-3) bring the sacrifice of prayer: of glory, blessing, praise, hymns, and gifts.

But Tertullian also spoke of something far more explicitly opposed to the Roman liturgy:

Citation: Tertullian of Carthage. “On Prayer.” §19

Tertullian is lecturing a portion of believers who, during their observance of the fast of the Stations (see §18 in “On Prayer”), would skip the (1-3) sacrifice of the Eucharist and only participate in the (4-5) celebration of the Lord’s Supper. They could skip the Eucharist only because it was a separate observance from the Lord’s Supper. Notably, the (4) consecration and the (5) Lord’s Supper were not part of the sacrifice: Jesus’ body and blood were not offered as sacrifice to God, as in the Roman liturgy.

Lastly, Tertullian notes in passing the (3) “Amen” spoken by the congregation over the Holy Thing, the eucharist, the sacrifice of the tithe offered to God.

Citation: Tertullian of Carthage. “De Spectaculis.” §25

To sacrifice is to make sacred by offering to God an acceptable gift. The eucharist is the offering—of sacred and holy sacrifice—that a Christian offers to God and God receives. It is the Holy Thing over which is uttered the corporate Amen.

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 8: Interlude

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 10: Origen of Alexandria

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 11: Cyprian of Carthage

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 13: Aphrahat the Persian Sage

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 17: Interlude

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 18: Athanasius of Alexandria

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 21: Eusebius of Caesarea

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 22: Dionysius of Alexandria

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 23: Gregory of Nyssa

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 27: Interlude

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 28: Basil of Caesarea

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 31: Ambrose of Milan