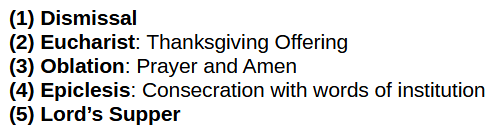

The original liturgy:

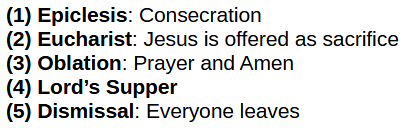

The Roman liturgy:

The Rise of Roman Catholicism

In Part 16: Apostolic Constitutions (375-380), we got hints on how the Eucharist and Lord’s Supper was ultimately combined and reordered into one Roman liturgy.

Only those items agriculturally related to the production of bread and wine were permitted to be sacrificed as the Eucharist at the altar. Those other items that used to be offered in the tithe for the previous 300 years were now delivered straight to the storehouse of the bishop, for later use by the bishop, presbyters, deacons, and the other clergy, not for the poor.

So we see hints in Apostolic Constitutions how the Eucharist was corrupted into the Roman liturgy. [..] Eventually, only financial support for the church as its own independent entity would remain.

Nothing would remain of the original Eucharist. The sacrifice of tithes, gifts, service, good works, gratitude, prayers, praise, hymns, and a pure heart and mind? Replaced by financial gifts to fill the coffers of the churches and the clergy that ran them. Greed was the root of this new evil.

You can see precisely how this happened. Given a brand new universal authority centered in Rome, it would just be a matter of time before every church was forced to implement these new policies. As soon as these changes were implemented, it would a few decades at most before people simply forgot about the old way of doing things.

As we continue this series, we will see how the innovations described by the “heretical”Apostolic Constitutions sit right into the middle of the era when certain other writers proposed the same changes: Cyril in 350, Serapion in 353, Hilary in c.360, Macarius in 390 and Chrysostom in c.400. In this interlude, we will discuss what else was going on in the late 4th-century and how it closely relates to what was described in the Apostolic Constitutions (and the other writers, as we’ll see).

The Rise of the Papacy

In 325AD, during the Council of Nicaea, the Metropolitan seat of Italy was with the Bishop in Milan. As part of its deliberations on jurisdictional disputes, the council cited a “custom of Rome,” which referred to the current practice of (the Bishop of) Metropolitan Rome being hierarchically inferior to (the Bishop of) Metropolitan Milan, by Rome having carved out a smaller defined and restricted geographic boundary within a single shared diocese. The council decided that both (the Bishop of) Metropolitan Alexandria and (the Bishop of) Metropolitan Jerusalem would have limited geographic scope under the provincial primacy of (the Bishop of) Metropolitan Antioch, as it had been with Rome under Milan. The precedent of the limited authority of the Bishop of Rome solved the problem of three Metropolitans within a single province. Far from Roman Primacy coming from the apostles, the Bishop of Rome did not even have primacy within his own diocese until 358 at the earliest.

In 370, Optatus of Milevus was the first to declare that Peter was the first Bishop of Rome, in direct contradiction to other patristic writers—e.g. Irenaeus and Eusebius—who recognized Linus as the first Bishop of Rome. The early church did not believe that Peter—an apostle—was ever a bishop of Rome, let alone a pope. This novelty would set the stage for what followed.

Sometime between 325 (Council of Nicaea) and 381 (Council of Constantinople), the Roman Empire reorganized its civil structure and the diocese of the East was split into two (Egypt and East). During this period, the ecclesiastical unit of the church changed from provinces to dioceses, to match the dioceses in the civil organization. No longer did one province contain three Metropolitans: Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria. Metropolitans Antioch and Jerusalem were in the Diocese of the East, while Metropolitan Alexandria was the only one left in the Diocese of Egypt. Thus did Alexandria incidentally become chief Metropolitan of its own diocese by an ecclesiastical restructuring into dioceses to match the civil arrangement.

Meanwhile as time elapsed, the Bishop of Rome, through political maneuvering, had effectively claimed the diocesan primacy from the Bishop of Milan, and the previous arrangement determined by the Council of Nicaea was forgotten or ignored. This was so effective and complete that a year after the Council of Constantinople, in 382, Pope Damasus I would declare at the council of Rome:

…

Therefore first is the seat at the Roman church of the apostle Peter ‘having no spot or wrinkle or any other [defect]’. However the second place was given in the name of blessed Peter to Mark his disciple and gospel-writer at Alexandria, and who himself wrote down the word of truth directed by Peter the apostle in Egypt and gloriously consummated [his life] in martyrdom. Indeed the third place is held at Antioch of the most blessed and honourable apostle Peter, who lived there before he came to Roma and where first the name of the new race of the Christians was heard.

Citation: “Council of Rome.” III.1 (382)

Damasus, who was bishop of Rome from 366 until his death in 384, was the first to successfully make this assertion. Amazingly, it worked!

Citation: Encyclopedia Brittanica, “St. Damasus I” (2022)

In an act of shrewd political maneuvering by Damasus with the support of two emperors, Antioch—which had the best argument for primacy among the Three Petrine Sees[1] of Antioch, Rome, and Alexandria—was relegated to third place. Just a generation earlier, only Antioch had even had the ecclesiastical primacy in its own province!

Notice that the while the Roman bishop was apparently “concerned” with the Petrine succession of Antioch and Alexandria,[1] the Encyclopedia Brittanica says he was concerned about the threat of Constantinople (or “New Rome”) to the primacy of Rome in the church. Why? Because since 330, Constantinople was the capital of the Roman Empire. As with the ecclesiastical provincial inferiority of Rome at the Council of Nicaea in 325, Rome was no longer politically superior even in its own diocese. The main threats to Damasus claiming the Roman Primacy were political not ecclesiastical, which the Encyclopedia Brittanica recognizes.

All the talk about the three Petrine Seats wasn’t to establish which of the three had the right to rule, but to establish that Rome was superior to Constantinople. Damasus was merely using Peter’s legacy as an excuse to fuel his own ambitions. Damasus could get away with the historical anachronism that Rome was the premier Petrine Seat because Antioch and Alexandria were religious pawns in a political game: they never had any chance of winning the primacy. Damasus was coopting—bribing[2]—the authority of two other Metropolitians to win the game of power over a fourth.

Damasus’ unilaterial declaration could not be opposed politically. Thus rose the Papacy in Rome and the Primacy of Rome at the same time as (1) the formal declaration of Christianity as the Roman religion and (2) the writing of the Apostolic Constitutions (and in the midst of the other writers who said the same). None of these were isolated from each other, but were inextricably linked. There were other “not coincidences” too.

The Errors of Jerome

Jerome—close friend of Damasus—would become his greatest ally.

Recall how the ecclesiastical structure had changed between the councils of 325 and 381? In his dispute with John of Jerusalem in 398, Jerome claimed that the Council of Nicaea had granted Antioch jurisdiction over Jerusalem in the diocese of the East and over Alexandria in the diocese of Egypt (which didn’t exist at the time!!!) because of the custom of the primacy of Rome. Jerome’s claim—whether an intentional deception or by an accident of history—was a logically and factually impossible historical anachronism.[3]

Combined with the political power of two emperors, Damasus and Jerome prevailed in their argument and were able to fabricate the doctrine of Roman Primacy out of thin air. Indeed, they were able to do this by citing as evidence the very historical record that disproved it.[4]

By no coincidence, this occurred along with the single greatest corruption of scripture—the Latin Vulgate (382-384). Why is this so significant to our discussion here? Because, as we first referenced in Part 9: Tertullian, Jerome conflated the Greek word musterion (“secret; mystery”) with the Latin word sacramentum (“oath or vow to the gods” or a “pledge”). This error would lead to the system of sacraments in the Roman Catholic Church and is the reason for a formal priesthood.

Thus did Jerome’s errors show the seeds of Roman and Papal Primacy, the church’s firm control over the translation (and thus interpretation) of scripture, the system of sacraments, and ultimately the Roman liturgy of the 6th or 7th century from out of nothing.

The Church Official

Alongside Roman Catholicism being declared the official religion of the Roman Empire, something interesting changed; civil taxes started flowing through the church: to the bishops. This is just like what we saw in Apostolic Constitutions: the tithes went directly into the house of the bishop! Thus did the tithes go to the benefit of the clergy and governing authorities, instead of the poor. This priestly acquisition of wealth and political power was extremely corrupting and extremely influential.

Speed of Change

Notice above how fast things changed?

In only a few decades, the churchmen had forgotten about the change in ecclesiastical structure (in large part because it matched the civil structure), and so created the Primacy of Rome out of an historical anachronism!

Over the course of two decades, Jerome committed key errors that would reverberate through Roman Catholicism to this very day.

The rising power of the clergy led to wealth accumulation and a deep corruption of personal and political power that it would use to introduce and enforce a flood of doctrinal innovations, many of them developing for the first time in the late-4th and early-5th centuries:

Papal and Roman primacy, papal infallibility, priestly celibacy, elevation of virginity and fasting over marriage, Mariology (immaculate conception, perpetual virginity, assumption of Mary, Mother of the Church), kneeling on the Lord’s Day, incense, candles, relics and images, veneration of the cross, baptismal regeneration, intercession of the saints, the title of Pontifex Maximus, ex communicare replaced by ex civitate, taking up the civil sword to persecute and kill the faithful, civil taxes flowing through the Bishops and priestly wealth acquisition, the church holidays (Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday), vestments, the system of sacraments, and the eucharistic alterations: the alteration of the liturgical order, transubstantiation, the sacrifice of the Mass, eucharistic adoration, communion on the tongue, the liturgical mixing of water with wine.

Throughout this series, we saw that for 300 years the patristic writers were more-or-less unanimous, differing only in the subtleties of their perspective. But starting around 370AD, things started changing, quickly, over a few decades: less than a single generation.

That list above is not even fully complete, but if one were to do a series like this one on each of those items, they would find exactly the same thing for almost everything on that list: no evidence in the first 300 years of the church—none at all—followed by the sudden arrival of the seeds of these doctrines in the late 4th century.

The Eucharist

And so we come back to the Eucharist, which had been a tithe offering prior to the consumption of consecrated elements in the Lord’s Supper. With a newly risen religion, headed by an authoritarian papacy and the growing legal enforcement of religious matters by the civil power of the sword, the ancient liturgy of the church stood no chance.

As we noted with the Apostolic Constitutions, given a brand new universal authority centered in Rome, it would just be a matter of time before every church was forced to implement the new policies contained in the Apostolic Constitutions. As soon as these changes were implemented, it would a few decades at most before people simply forgot about the old way of doing things, with newer generations never realizing what had been lost. Given the new civil power, the church could severely punish anyone who dissented, and it did with vigor.

If you don’t believe it is possible for people to do a 180° turn within one generation, just consider how Jerome defended his novelty on Roman Supremacy by citing evidence that objectively destroyed his viewpoint. Such is the sheer power of propaganda, to invert truth and fiction.[4]

Given all that was going on, it is thus trivial to see how the tithe was quickly displaced. It would take a while before the doctrines of “Real Presence” and transubstantiation could be developed, but it is easy to see how it happened. We are lucky to have the Apostolic Constitutions, because it gives us a peek into how within a few years a change in liturgy—alongside an authoritarian change in church leadership—could have effects that would last more than 1600 years.

Footnotes

[1] Since Damasus, the Roman Catholic Church’s Popes have agreed:

Citation: Pope Gregory the Great, “Book VII, Letter 40.” (590-604)

Citation: Pope Benedict XVI, “Called to Communion: Understanding the Church Today.” II.2.b “The Petrine Succession in Rome”

[2] Everyone involved knew that the Bishops of Antioch and Alexandria would have more power with Rome at the head than if the Bishop of Constantinople prevailed. Rather than Damasus simply lying about which Petrine Seat should be primary, he implicitly linked the political rise of all three Bishops together over everyone else. The payment for giving Antioch and Alexandra that political power was giving Rome the primacy. Thus, Antioch and Alexandra were incentivized to affirmatively support Rome’s novel claim of Primacy. The evidence suggests that Rome needed Alexandria’s support more than Antioch, which is why it was given the second priority.

[3] This ignorance of the historical changes to the layout of the Roman provinces and dioceses is closely related to the failure to determine the identity the thirteen horns and the little horn of Daniel’s prophecy. The division of the Empire by Diocletian into 12 dioceses ruled by their own vicarius in 292 is well known, but the intermediate division into 13 in the late 4th-century is rarely acknowledged, if it is even known at all, as many modern historians jump straight from initial 12 to the “final” 14.

See: “Eschatology: Ten and Three Horns” (including footnote 1).

[4] This is precisely what FishEaters has done: citing as evidence for the Roman liturgy the very historical record of the first 300 years of the church that disproves it. This is also implicit in the claim by commenter Bardelys who wrote: “As well sourced as this post was, Derek of all people would know that there’s just as much, if not more, evidence on the other side (Fisheaters has a great write-up on the eucharist)”

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 19: Ephraim the Syrian

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 23: Gregory of Nyssa

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 28: Basil of Caesarea

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 40: Conclusion