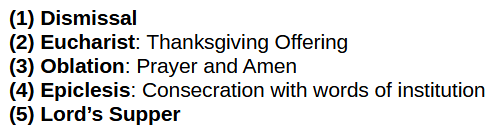

The original liturgy:

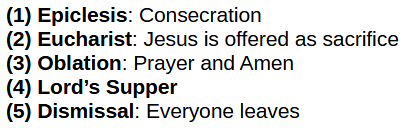

The Roman liturgy:

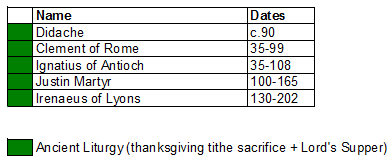

Irenaeus

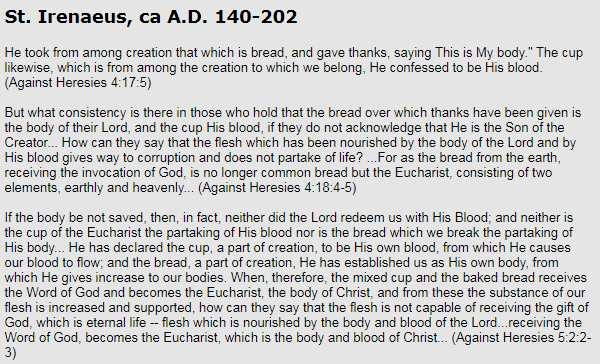

The first quote is just the plain observation that Jesus spoke the words of institution (“he confessed”) over created agricultural products: bread and wine. If anything is to be noticed at all, it is that Jesus called created things his body and blood. This is hardly the basis for transubstantiation or the “real presence:” after saying the words of institution, the bread and wine remained created things. As we will see below, Irenaeus’ theology repudiates any notion of transubstantiation, but for now this quotation merely raises red flags.

We need only concern ourselves with the last two quotes. Before we begin, a warning is in order:

As an intellectually- and academically-oriented writer, I find this to be deeply offensive, especially because these mistranslations are not disclosed to modern readers by editors, apologists, and scholars. In addition to deceiving countless people, this helps to create unnecessarily hostile situations like the one that inspired this series, as well as cultivating overconfidence in Roman Catholics. It harms the possibility of dialogue

However, before we go into that, let’s first see if these quote snippets, which purport to support a Roman liturgy, fit within the wider context of Irenaeus’ other works.

Why do I start here? Because in the modern Roman liturgy, the participants receiving the bread on Sunday kneel down. The early church forbid kneeling on Sunday on theological grounds:

“Forasmuch as there are certain persons who kneel on the Lord’s Day and in the days of Pentecost, therefore, to the intent that all things may be uniformly observed everywhere (in every parish), it seems good to the holy Synod that prayer be made to God standing.” Citation: Council of Nicaea, Canon XX (325AD)

But the Roman liturgy requires it! Such a “little” discrepancy really highlights how the Roman liturgy was subject to development over time: it was not original.

Why do I cite this next? Because it is nothing like the Roman liturgy!

Irenaeus identifies the sacrifice mentioned by Malachi as prayer, then identifies the acceptable sacrifices as those of service, prayer, praise, blessing, and the bringing forth of fruits—agricultural products—for nourishment. He’s describing the (2) eucharist and (3) oblation: the tithe and the prayers, praise, and service of thanksgiving that are offered together as a sacrifice to God for use by the poor. It is precisely as we saw in Justin Martyr: “to use it for ourselves and those who need, and with gratitude to Him.”

Then, upon completion of the (3) oblation, Irenaeus describes the (4) epiclesis where the Holy Spirit is invoked upon the already sacrificed eucharist in order to make the bread and wine the body and blood of Christ.

Shall we talk more about how the purpose of the tithe of food is for nourishment? Or how the body and blood of Christ are “antitypes” (that is, figures)? Or that these acts are performed as a spiritual remembrance? The Roman liturgy is absent and in its place the true liturgy of the church.

Now, let’s move to “Against Heresies”, which very long.

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 1. §13.2

Once again, the English translations hide the meaning of the Greek. This is especially egregious, because the word (2) “eucharist” is replaced with (4) “consecrate.” This is a rather plain attempt to merge the two into one unit, as in the Roman liturgy, for in the English translation it looks as if the Epiclesis coincides with the Eucharist. But Irenaeus describes a Eucharist that takes place prior to and separate from the consecration in the words of institution (or invocation; epiclesis).

For reference to the Greek words highlighted above, see Roman Catholic J.P. Migne’s Patrologia Graeca (1857–1866) in vol VII, 580. In a footnote at 579n Migne translates this to Latin as “Consecrare, inquam, non gratias agere.” which translated is “To consecrate, I say, not to give thanks.” Migne inserts his opinion in Latin, while acknowledging the original Greek. So simple is it to rewrite history, 1984-style. But, most insidious, is that it is very hard for Protestants to know that this intentional mistranslation has taken place.

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 1. §14

This is a passing reference to the (3) Oblation which concludes with a corporately spoken “Amen.” It is a reference to 1 Corinthians 14:16…

…upon which it is established that the Amen spoken in the Eucharist is Apostolic, which is why it has been referenced by many of the writers we examine in this series. The early church understood Paul’s instructions for the Eucharist—the literal giving of thanks—to conclude with a corporate “Amen.”

The “Amen” forms a hard stop between the (1-3) sacrifice of the eucharist—the tithe—and the (4-5) celebration of the Lord’s Supper of consecrated elements. In the modern era, with fiat money having replaced agricultural products in the tithe, Protestants have largely separated the observance of the former and that of the latter. Churches still purchase the elements from out of the eucharist—tithe—but they no longer observe these ceremonies at the same time. It is why Protestants don’t call the Lord’s Super “the Eucharist,” as do the Roman Catholics: because they are separate observances, only related by where the elements come from.

Now there is a discrepancy in the text:

…

“For as the bread, which is produced from the earth, when it receives the invocation (epiclesin) of God, is no longer common bread, but the Eucharist, consisting of two realities, earthly and heavenly…”

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 4. §18.5

Translators saw summons and did not know what to do with it. Elsewhere in the text Irenaeus used the term “epiclesin” in other contexts, so not knowing what to do with the implied theology of “ecclesin,” they instead assumed that the word chosen was a mistake. So they switched it out with invocation.

Once again we cite J.P. Migne (Patrologia Graeca, vol VII, 1028n) who made a note that he preferred invocation. I bet he did! This change alters the text to make it seem like the (2) Eucharist receives the (4) invocation, that is, it was the invocation that turned it into the Eucharist. This is a rather plain attempt to insert the Roman liturgy onto the lips of Irenaeus.

So if “summons” is correct, who is doing the summons? What does it mean?

It is God himself who has summoned the tithe into the storehouse. Irenaeus simply continues his referencing of Malachi (as he did in Fragmant 37 above in reference to Malachi 1:11).

Of course if the mistranslated version was correct, Irenaeus would have been logically contradicting himself (e.g. with Fragment 37) by portraying multiple liturgical orders. Nonetheless, this version is very popular among Roman Catholic apologists. Now, you will not be surprised to note that FishEater has indeed cited the mistranslated version.

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 4. §18.1

Here Irenaeus discusses the Eucharist as a gift, which is the same language when we looked at Clement of Rome’s Eucharist. The tithes are the firstfruits of created things, and they are offerings of thanksgiving and gratefulness.

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 4. §18.2

Here Irenaeus connects the Eucharistic tithe offering to the offerings of the Jews, noting that they have changed merely in form while still fulfilling the same purpose. These tithes are still the offerings of thanksgiving prescribed in the Old Testament. Irenaeus’ reference to the widow makes the same point that Clement of Rome did, as we noted in part 5.

…

Now we make offering to Him, not as though He stood in need of it, but rendering thanks for His gift, and thus sanctifying what has been created. For even as God does not need our possessions, so do we need to offer something to God; as Solomon says: He that has pity upon the poor, lends unto the Lord. Proverbs 19:17 For God, who stands in need of nothing, takes our good works to Himself for this purpose, that He may grant us a recompense of His own good things, as our Lord says: Come, you blessed of My Father, receive the kingdom prepared for you. For I was an hungered, and you gave Me to eat: I was thirsty, and you gave Me drink: I was a stranger, and you took Me in: naked, and you clothed Me; sick, and you visited Me; in prison, and you came to Me. Matthew 25:34

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 4. §18.4,6

Having established the basis for the eucharist—thanksgiving—offering of the tithe in the church, Irenaeus now notes that its purpose is to help those in need, especially by giving them food and drink. Even here we are still back where we started in Part 2: The Didache. Irenaeus spends a lot of words setting up the scriptural foundation of the Eucharist as a thanksgiving tithe offering. As before, the Roman liturgy is absent, for the Roman liturgy has no conception of the Eucharist as an offering or sacrifice to God of food for those in need. Even when translators swap out one word for another, it just creates a Frankenstein’s monster of an irrational mess that still fails to conform to the Roman liturgy.

He does not speak these words of some spiritual and invisible man,

but [he refers to] that dispensation [by which the Lord became] an actual man, consisting of flesh, and nerves, and bones — that [flesh] which is nourished by the cup which is His blood, and receives increase from the bread which is His body. And just as a cutting from the vine planted in the ground fructifies in its season, or as a grain of wheat falling into the earth and becoming decomposed, rises with manifold increase by the Spirit of God, who contains all things, and then, through the wisdom of God, serves for the use of men, and having received the Word of God, becomes the Eucharist, which is the body and blood of Christ; so also our bodies, being nourished by it, and deposited in the earth, and suffering decomposition there, shall rise at their appointed time, the Word of God granting them resurrection to the glory of God, even the Father, who freely gives to this mortal immortality, and to this corruptible incorruption, 1 Corinthians 15:53 because

in order that we may never become puffed up, as if we had life from ourselves, and exalted against God, our minds becoming ungrateful; but learning by experience that we possess eternal duration from the excelling power of this Being, not from our own nature, we may neither undervalue that glory which surrounds God as He is, nor be ignorant of our own nature, but that we may know what God can effect, and what benefits man receives, and thus never wander from the true comprehension of things as they are, that is, both with regard to God and with regard to man.

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 5. §2.2,3

Earlier, when Irenaeus had been discussing our unconsecrated tithe offerings, he described how they enrich us spiritually. Here he talks about how the consecrated bread nourishes us physically. I shared this very long quotation because the physicality of his description when discussing the consecrated bread is very clear. What, then, is the significance?

First, Irenaeus mentions that the bread and wine are part of creation. They are created things. They are not in the appearance of created things (i.e. it isn’t transubstantiation: the species of bread, the substance of Christ’s real flesh). It is very real, very visceral, very created.

Second, Irenaeus treats the elements as if they are digested and used to build the substance of the flesh, which, if they were actually fully bread and wine, they would do. Many Roman Catholics would find this concept utterly heretical.

Third, Irenaeus describes the bread metaphorically in terms of how it starts as seed, dies, and eventually is turned into food that we eat. This is a figurative symbol of our own death and resurrection.

Fourth, Irenaeus wrote this to contest the Gnostics, to argue that Jesus had a real, physical body and that we retain a body of flesh when we die, just as the risen Christ still has physical flesh that will one day consume actual physical wine at the Marriage Feast of the Lamb. This is not transubstantiation because, as we saw in our examination of Fragment 37 and in our analysis here, the bread and wine remain very real, very created. This is made even clearer elsewhere:

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 5. §33.1

Of course for Christ and the disciples to drink the fruit of the vine, they must have physical flesh! Notice too that the newly risen flesh comes from the cup, not the bread.

In summary, what Irenaeus describes is very much not what Rome teaches. FishEater’s use of this quotation does not evidence a Roman liturgy.

But there is a more significant problem with the translation. Notice how the passage FishEater cited hinges on this key phrase:

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 5. §2.3

There are two versions Against Heresies. A Latin translation that is more complete, and a fragmentary Greek original version. However, in this particular passage, the two sources do not agree. We will let Phillip Schaff explain:

The Greek text, of which a considerable portion remains here, would give, “… the Eucharist becomes the body of Christ.”

Citation: Phillip Schaff, “Ante-Nicæan Fathers, volume I“, note 4462

And so the passage should read:

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 5. §2.3

In 1885, the translators Alexander Roberts and William Rambaut simply chose the Latin over the original Greek when they rendered the passage into the English version we have now, the one that the Roman Catholic apologists all use to imply that the Eucharist is created at the consecration rather than before it. They knew precisely what they were doing, and they’ve deceived countless numbers of Protestants and Catholics in the process. Had they rendered it accurately, it would be explicitly opposed to the Roman liturgy, which of course it is!

If Irenaeus wanted to say that the the bread and wine became the eucharist and the blood and body of Christ at the same time, he would only needed to have said:

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons. “Against Heresies.” Book 5. §2.3

But he added the qualifier “the Eucharist of the blood and the body of Christ is made” because he had to qualify which Eucharist he was talking about. He was distinguishing between the unconsecrated and the consecrated eucharist. Even mistranslating the passage cannot hide this subtle point.

In this examination alone, we’ve found three intentional mistranslations that changed the original text from a Protestant-style liturgy into a Roman liturgy. These mistranslations are then commonly repeated by apologists as if they were real. I cannot adequately express precisely how offensive this is to the truth. I cannot even imagine how many Roman Catholics have been deceived by this, arrogantly proclaiming the truth to be on their side, even as they were as far from it as possible.

Reference:

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 8: Interlude

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 10: Origen of Alexandria

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 11: Cyprian of Carthage

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 12: Hippolytus of Rome

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 13: Aphrahat the Persian Sage

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 18: Athanasius of Alexandria

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 21: Eusebius of Caesarea

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 22: Dionysius of Alexandria

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 23: Gregory of Nyssa

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 28: Basil of Caesarea

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 36: Irenaeus, Revisted

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 40: Conclusion

Pingback: The Eucharist, Redux #1