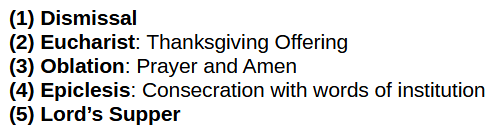

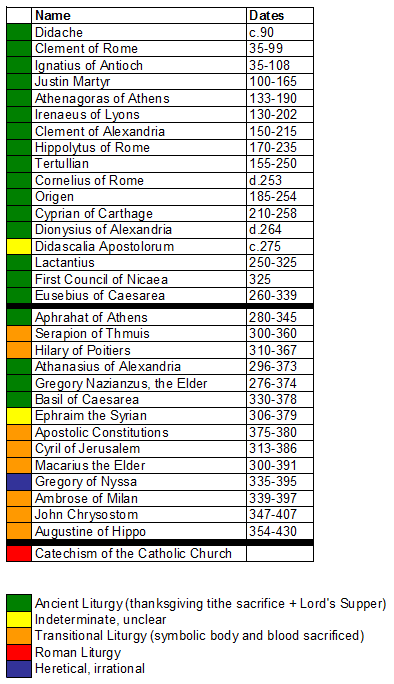

The original liturgy:

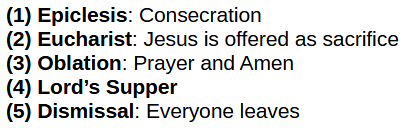

The Roman liturgy:

Catechism of the Catholic Church

One of the big problems with Roman Catholics is that they are often mistaken about what their own church teaches. Though the Magisterium and the infallible pope are supposed to provide all of the correct beliefs, Roman Catholics are largely left to their personal efforts to try figure out what they are supposed to belief. This is demonstrated, in large part, by how readily they are to apply their personal opinions onto non-Catholics as if they were dead certain about what is orthodox or non-orthodox belief.

One of the strangest things I’ve found in online interactions with Roman Catholics is how they object to non-Roman Catholics citing what Roman Catholics actually believe. They think, quite seriously, that I am lying about what I’m saying, even though most of what I argue comes from Roman Catholic sources directly. Indeed, a lot of what I say is acknowledged by the Roman Catholic Church itself. It’s not just the Catholic Encyclopedia…

Citation: Adrian Fortescue, “The Origin of the Mass.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol 9. (1910)

…that agrees with me that the Roman liturgy is not found early in the church, but it includes the Catechism of the Catholic Church itself. As we go over the section on the Eucharist, we’ll see a couple of cases that actually confirm a few things we saw in this series.

As early as the second century we have the witness of St. Justin Martyr for the basic lines of the order of the Eucharistic celebration. They have stayed the same until our own day for all the great liturgical families. St. Justin wrote to the pagan emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161) around the year 155, explaining what Christians did:

Then we all rise together and offer prayers for ourselves . . .and for all others, wherever they may be, so that we may be found righteous by our life and actions, and faithful to the commandments, so as to obtain eternal salvation.

When the prayers are concluded we exchange the kiss.

Then someone brings bread and a cup of water and wine mixed together to him who presides over the brethren.

He takes them and offers praise and glory to the Father of the universe, through the name of the Son and of the Holy Spirit and for a considerable time he gives thanks (in Greek: eucharistian) that we have been judged worthy of these gifts.

When he has concluded the prayers and thanksgivings, all present give voice to an acclamation by saying: ‘Amen.’

When he who presides has given thanks and the people have responded, those whom we call deacons give to those present the “eucharisted” bread, wine and water and take them to those who are absent.

The CCC’s take on Justin Martyr is quite interesting. It acknowledges that what is offered are (2) prayers, praise, and thanks, which concludes with (3) a corporately spoken Amen. Many Roman Catholic apologists are completely unwilling to admit this! They might even call you a liar for pointing it out. Interestingly, the CCC acknowledges that the sacrificed bread is called the ‘eucharisted‘ bread.

Of course, the CCC doesn’t go far enough with this acknowledgment. What it fails to mention is that, in Justin Martyr’s work, the unconsecrated eucharisted—sacrificed—elements are only afterwards consecrated and not offered as a sacrifice. It just leaves this out, while acknowledging the rest of the important details.

The anaphora: with the Eucharistic Prayer – the prayer of thanksgiving and consecration – we come to the heart and summit of the celebration:

In a stark comparison to the CCC’s acknowledgment of Justin Martyr’s thanksgiving—eucharist—this is a bald-faced lie. In terms of every thanksgiving described in the first 300 years of the church, this is a lie. The anaphora—which exists nowhere in scripture—combines the prayer of thanksgiving and the consecration into one. But in Justin Martyr (and many others), the sacrifice of thanksgiving was separate from the consecration. The already sacrificed “eucharisted” bread and wine were only thereafter consecrated. The “eucharistic” thanksgiving prayer was absolutely separate from the prayer of consecration (which included the words of institution) by the corporate “Amen.” The Oblation preceded—and was separate from—the epiclesis (or consecration).

From the very beginning Christians have brought, along with the bread and wine for the Eucharist, gifts to share with those in need. This custom of the collection, ever appropriate, is inspired by the example of Christ who became poor to make us rich: [1 Cor 16:1; 2 Cor 8:9.]

Now we go back to the CCC calmly noting that the original ‘eucharist‘ was a freewill thanksgiving offering of a tithe or gifts. Interestingly, it cites Justin Martyr as evidence. Even Roman Catholic apologists struggle to admit what the CCC just comes out and says.

Did you know that the Roman Catholic church admits that the ‘eucharist‘ is a thanksgiving offering of tithes? Sure, it argues that it is more than just that, but I’ve seen Roman Catholics completely lose their mind—spewing curses and insults—at the very suggestion that the thanksgiving includes tithes.

On the other hand, does any Roman Catholic church actually practice the collection of food for the poor as part of its thanksgiving? They certainly ask for money, but unlike food, money can be—and is—used for a whole lot of purposes other than helping the poor.

The crux of the issue is that in the first 300 years of the church, the thanksgiving was not a sacrifice of the body of Christ. There is a massive gap between Christ and the Apostles and the Roman Catholic Church.

- the gathering, the liturgy of the Word, with readings, homily and general intercessions;

- the liturgy of the Eucharist, with the presentation of the bread and wine, the consecratory thanksgiving, and communion.

This is the biggest lie the Roman Catholic Church has ever told its members. If this series has showed us anything at all, it is that the ancient liturgy of the first 300 years of the church is utterly incompatible with the Roman liturgy. The substance of the liturgy has indeed changed, and changed dramatically. In particular, the thanksgiving was not consecratory for 300 years.

Curiously, the CCC1356 says “If from the beginning…” as if there is some doubt that it really is from the beginning. I mean, sure, the evidence is overwhelming that it wasn’t that way from the beginning, but they clearly don’t want you to think that. This is such a deviously subtle lie. No Roman Catholic is going to read this and think “oh, the CCC isn’t sure if its Eucharist really is Apostolic.” And yet, there it is.

Many Roman Catholics claim that Melchizedek offered bread and wine, even though these were not sacrificed. Though the only thing that Melchizedek offered to God was praise:

“Blessed be Abram by God Most High,

Creator of heaven and earth.

And praise be to God Most High,

who delivered your enemies into your hand.”

Then Abram gave him a tenth of everything.

Thus, many Roman Catholic apologists, including FishEaters in “The Eucharist” appear to be unaware that, according to the CCC, the gifts of bread and wine that Melchizedek presented were created things, that is, unconsecrated food offered to men. Logically, if Christ’s offering was of the same type as Melchizedek’s offering, then Christ had to be offering unconsecrated food—bread and wine—to men, not to God. In the face of transubstantiation, the analogy breaks down.

The Eucharist is also the sacrifice of praise by which the Church sings the glory of God in the name of all creation. This sacrifice of praise is possible only through Christ: he unites the faithful to his person, to his praise, and to his intercession, so that the sacrifice of praise to the Father is offered through Christ and with him, to be accepted in him.

Are you surprised to hear the CCC acknowledges the basic, essential nature of the thanksgiving?

The Roman Catholic error was adding onto this. Since the CCC already admits that during the first 300 years of the church, this was the thanksgiving, all we have to do is show that this was the only thanksgiving in that time. And we have done just that. The Roman liturgy is completely absent.

This is an invalid argument. It does not logically follow that being a memorial of a sacrifice makes it a sacrifice itself. Indeed, were this anywhere outside the CCC, such a statement would be understood for the absurdity that it is. Normal people, without ideological commitments, would see this for the irrational statement that it is: a memorial of a thing is obviously not the thing itself.

For the words of institution to carry a “sacrificial character” requires the prior acceptance that Christ’s offering of the bread and wine was a sacrifice. If, for example, we didn’t assume that Christ was offering the bread and wine as a sacrifice, then it wouldn’t follow that the words of institution had a “sacrificial character.” Thus, the CCC is obviously engaging in circular reasoning (i.e. begging the question).

The Roman Catholic response to this tends, in my experience, to say that it is a mystery, which is a massive cop-out.

That’s not what a sacrifice is. That isn’t how the Bible defines a sacrifice. That isn’t how the early church writers defined a sacrifice. Sacrifices do not make present other sacrifices by the fact of being a memorial of a sacrifice.

The CCC claims that the Eucharist is a sacrifice because it applies the fruit of a sacrifice. What this means is that the Eucharist is a propitiation for the remission of sin, something that no writer in the first 300 years of the church ever asserted. Such claims only emerged around 350AD. To defend its novelty, the CCC cites the Council of Trent from the 16th century.

Roman Catholic apologists like to say that even though the literal body and blood of Christ are being offered as a sacrifice to God, they do not actually re-sacrifice, they merely re-present. CCC#1366 is logically incoherent and an historical anachronism. The argument that Christ is being re-presented—which is the official belief—instead of re-sacrificed is based on a chain of invalid and incoherent reasoning. Labeling it something else—re-presentation—doesn’t keep it from being idolatry.

Congratulations on your efforts.

“The memorial of a sacrifice becomes a sacrifice. ”

That’s an easily understood part of the flesh to do that. Examples are seen in scripture. I wish you could have had someone argue the Catholic side better. I didn’t see a response to my attempted counter argument on behalf of BtM. The “argument” was that since the ground Moses was standing on at the burning bush was made holy (and I think there are other similar examples), couldn’t the bread be made holy, and therefore treated the same as an actual sacrifice?

OTOH, We are told to examine ourselves prior to partaking of it. If Paul thought it was an actual sacrifice, couldn’t he have spoken of it more plainly?

I am familiar with this argument, though it’s not a very good argument. Do you remember all the way back in Part 2: The Didache?

Even the earliest of early writings identifies the thanksgiving offering as being holy. It’s not even a memorial at that point, it’s just a tithe. The tithe is holy.

Remember how in Part 10: Origin, the unconsecrated bread represented a double-portion?

Of course if the unconsecrated bread and wine are holy, so too must the consecrated bread and wine be holy. But how was it made holy? It was already holy when it was sacrificed. Indeed, it was holy before it was sacrificed. In Part 11: Cyprian, he described the holy gift of her tithe that a woman brought in a box, but she was turned away from actually offering the holy gift.

The notion that only sacrificed things can be holy is…. not valid.

I think what they want to say is that everything that is holy is, in some way, sacrificial (like praise, prayer, hymns, etc.). Sacrifice means “to make holy” so anything that is made holy is, by definition, a sacrifice.

But that doesn’t make the bread and wine that Jesus served his disciples any more of a sacrifice than him washing their feet. Everything holy is a kind of sacrifice, but that doesn’t make the consecrated elements a special kind of sacrifice, that is, specifically a propitiatory sacrifice.