This is part of a series on the Roman Catholic sacraments. See the index.

In my previous post, “Why is the Sacrament of Marriage Important?” I explained the reasoning behind the Roman Catholic idea of grace. Today, in response to this comment, I will explain how the Roman Catholic understanding of sacraments led directly to its priesthood.

Note: Much, but not all, of what is written here also applies to Orthodoxy.

The Sacred Secret

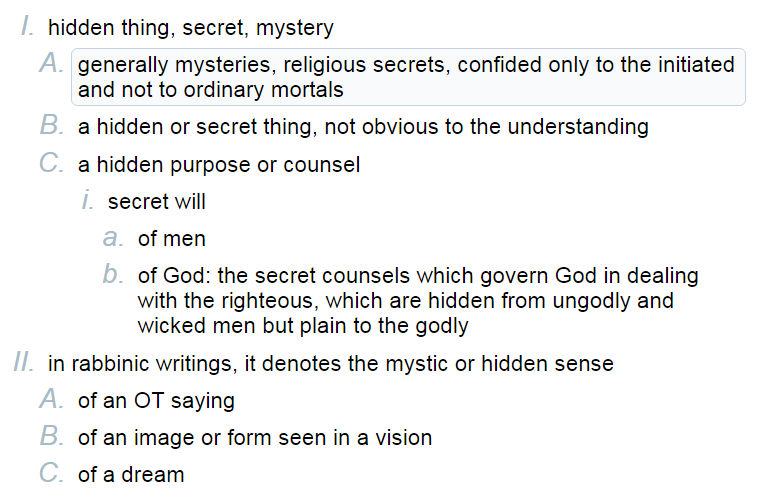

In Ephesians 3:2-12, Paul describes a “mustērion”, a sacred mystery or secret. Please read that passage, if not the whole letter itself, so you understand exactly what Paul is saying in the full context of the passage, as I will only be sharing snippets.

First, the secret was once truly a mystery: hidden, unknown, and unknowable.

the good news to the Gentiles about the unsearchable riches of Christ

the sacred secret, which for ages has been hidden in God who created all things

Second, it has now been made known for all.

So when you read this, you will be able to understand my insight into the sacred secret of Christ

it has now been revealed to his holy apostles and prophets by the spirit

…to bring to light for everyone what is the administration of the sacred secret

…through the church the multifaceted wisdom of God would now be made known to the rulers and the authorities in the heavenly places.

In particular, we know that Paul received the direct revelation of Jesus Christ after he was visited by the Spirit on the Road to Damascus. So what is this secret that Paul speaks of in Ephesians? It is sharing of the gospel of Jesus Christ and of his body, the church—congregation—of believers who put their faith in Christ in the promise of salvation, that is, a future resurrection after death. For Paul himself received this grace in order that he might share it to others.

this grace was given so that I could proclaim the good news to the Gentiles

This was consistent with his purpose throughout the ages that he accomplished in Christ Jesus our Lord, in whom we have boldness and access to God with confidence through our trust in him.

In summary, the sacred secret of the Gospel of the Messiah, Jesus Christ was hidden in the Old Testament, but was revealed by Christ himself and fully revealed by the coming of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost. Through the Great Commission—the Administration of Grace or evangelism—the gospel is now revealed to all who would hear.

But this is not how the Roman Catholic reads the passage, for they do not read the Greek, but the official version of the Bible in Latin.

The Mystery

In Latin, the word sacramentum originally meant “oath or vow to the gods” or a “pledge”. In the late 2nd century, Tertullian is alleged to have translated the Greek musterion into the Latin sacramentum[1], bringing the sense of “secret; mystery” alongside the idea of an “oath, vow, or pledge”, even though the words did not mean the same thing.[2] In the late 4th century—when Roman Catholicism arose—Jerome would conflate them explicitly when translating the Greek Bible into Latin in the Vulgate. Augustine would later identify hundreds of sacraments—rituals, ceremonies, and objects worthy of personal devotion. It wouldn’t be until the Council of Trent (1547) that the sacraments would be finalized into the seven we know today.

Without the support from the mistranslations in the Latin Bible, the doctrine of sacraments cannot be found in the Bible. It does not exist in the original Greek.

The Latin meaning would eventually be transferred into English where the meaning of “secret” (a thing hidden, but known and knowable) was replaced with “mystery” (a thing hidden, unknown, and unknowable). Indeed, the liturgy of the Roman Catholic Mass opens with:

In Roman Catholicism (and Orthodoxy), the role of grace is a mystery. Remarkably, Roman Catholicism can no longer explain what Paul had stated was now made known to all, including the apostles (from whom Roman Catholics claim to have received the Word of God) and the Gentiles.

In any case, in conflating the sacred secret (“a thing hidden, but known and knowable”) of the gospel of Christ with sacrament (“oath, vow, or pledge to God”), the idea of a sacrament took on a permanent ritualistic nature. The sacraments were made a type of vow to God. They were granted a physical manifestation of a spiritual mystery.

Baptism as a sacrament is a vow or pledge before God that is manifested in a physical act representing the underlying mysterious cleansing from sin. This is why in Roman Catholicism, you are not saved if you are not baptized, because the sacrament was not physically administered. A confession of faith is insufficient.

Marriage as a sacrament is also a vow or pledge. Like the ancient Roman oath upon which the Sacrament of marriage is based upon, the penalty for breaking the oath is greater than those who had not taken the sacrament. This is the reason why Roman Catholics separate sacramental and non-sacramental marriage. The sacred bond of marriage is thus contained within in the vow itself, not the physical act of joining.

Ultimately, however, Roman Catholicism only understands the outward—ritual—act and cannot explain the inward—mysterious—act of God. It can only blindly tell its congregants to do the thing, without fully understanding the why. It is the blind leading the blind, for nothing is revealed by the church. It also cannot separate the two: in Roman Catholicism, one must participate in the outward sacrament in order to receive the inward effects. It is not, for example, sufficient to make a confession of faith before God for the salvation of sins.

The Priesthood

And so we come to the priesthood. According to Roman Catholicism, when Paul speaks of the “Administration of Grace” and the “Administration of the Mystery” (for grace is the sacred secret or mystery), he is referring to the role of the church to, quite literally in the official Latin translation, administer the sacraments. In order to do this, a priesthood is required. It is thus the role of priests to administer Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Penance, Anointing of the Sick, Marriage, and the Holy Orders. In general, the lay person does not administer the sacraments.[3]

Roman Catholicism believes that Paul was establishing a priesthood to administer grace to the body of Christ. By selectively reading Paul, they can say that Paul was one of its first priests selected by God:

Notice that Paul (supposedly) received a special grace, a unique ability that he received that was a working of God’s power that allowed him to reveal the sacraments. Does this sound familiar? It should. I wrote about this in my previous post. Recall that in his “Becoming Catholic” series, Joshua Charles makes a revealing comment in his commentary on Ignatius:

Citation: Joshua Charles, “Becoming Catholic #10.” Church Authority, and Saint Ignatius the Red Pill, Part 5—Roman Finale.

Like all Roman Catholics steeped in Roman Catholicism, Charles understands grace to be a means or ability that is possessed. This is no mistake, for it is the foundation of the priesthood, and indeed all of the sacraments, including marriage: only a priest can officiate a truly valid marriage.[3]

Such is the power of reading whatever you want to read into scripture. From Paul’s words that reveal the secrets of God to all Christians, Roman Catholicism has twisted the Gospel of Christ into a mystery and produced a closeted priesthood made up of elites who control who can receive the grace of God. This brings to mind the words of Christ to the Pharisees:

The Confusion

The Roman Catholic teaching is confusing. It doesn’t make sense. It does not enlighten.

Here are some sample comments to illustrate:

The error, of course, is that marriage does not confer grace any more than baptism confers salvation. The sacraments, as a concept, represent invalid reasoning from the words of Paul, especially with respect to Tertullian’s conflation of the Greek with the Latin because he viewed baptism as a pledge. Roman Catholics can’t figure out the mystery because it makes no sense to begin with.

Even if baptism represented a public pledge of fealty to Christ, it wouldn’t make sacraments (i.e. a vow or pledge) out of marriage or the eucharistic tithe offering. To do so makes the logical error of assuming the inverse: “A⟹B, therefore B⟹A.”

Again, the word “secret” and the word “sacrament” are not the same words. They have completely separate etymologies in two different languages and the latter only gained the meaning of the former after the two were conflated by Tertullian by secular analogy and by fallacious reasoning. There is no such thing as a sacrament of grace in the Bible. Of course sacred vows—sacraments—certainly exist, but Jesus explicitly told us not to make them. Lastly, we know precisely where grace is and isn’t: it is only found in the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ’s sacrifice for sin and in our faith in him as our Lord and Savior, for…

Grace—the sacred secret—is right there for all who seek it. It is like the washing of a dirty garment, made spotless and clean. In very real terms, it is the defeat of death and the promise of eternal resurrection in a new incorruptible body. In Ephesians 2, just one chapter earlier, Paul describes this grace:

That is grace.

The ins and outs of Roman Catholicism are complicated and difficult. They are a heavy burden to bear. But the real bond of marriage is not a mere spiritualized metaphor, but a description of a real spiritual (and physical) joining that actually exists. Whether the joining of a husband and wife or the joining in a covenant between God and his people, that bond is not metaphor, but real.

The reason every explanation is vague is because Roman Catholics have no answer. They can only offer you a mystery—an unknown and unknowable secret—that you must blindly accept. By contrast, the mystery—a knowable secret—is solved in the words of Jesus, Paul, Peter, and John. It is no longer a mystery to believers and has not been since The Day of Pentecost.

The rituals of the sacraments add human action—the vow, pledge, or consent (as in Marriage)—to the saving grace of God. This is fundamental to the Roman Catholic understanding of what a sacrament is. Etymologically, they are historical legal artifacts of the Roman military oath.

Rebuttals

The brothers Cyril and Methodius (826-885)—who first translated the Bible into Slavic—came much to late to be relevant here. The development of the sacramental doctrine occurred long before the formation of the first Slavic Bible in 865 and the split of Orthodoxy from Roman Catholicism in 1054, and so has no relevance to the association between the conflation of the sacred secret of grace described by Paul and the Roman sacred oaths, let alone deciding which rituals were sacraments and which were not, which came later.

Basil of Caesarea (330 to 378) and John Chrysostom (347-407) were from the period of the late-4th century, when the doctrine of sacraments as mysteries was primarily developed[1] and Jerome made his translation. They were both native speakers of Greek, so it is unclear what the relevance of the Church Slavonic word is. Roman Catholicism arose in the late 4th century alongside a flood of doctrinal error, including development of idea of sacraments.

Perhaps the claim is that Orthodoxy was never influenced by the Latin usage of the term? This is plainly incorrect. The influence of the Vulgate on the church was indeed profound, and Tertullian’s use of both terms together clearly resulted in both the idea that the sacred secrets were sacraments and its inverse: that the sacraments were sacred secrets. These ideas would be firmly embraced and developed by native speakers of Greek. So strongly was this influence, that the Greek word took on the meaning of the Latin word!

It doesn’t matter that the Church Slavonic and English words for “mystery” do not mean sacrament, as these were not used to develop the doctrine. This is why Jack—using an English translation—did not understand that when Paul called marriage a mystery in Ephesians 5:32, “he” was also calling it—by the much later tradition—a sacrament. Even though the official Roman Catholic and Orthodox belief is that “This is a profound mystery” is equivalent to “This is a profound sacrament”, the reason for this equivalence was lost with the more recent translations, even as the doctrine itself was not lost.

This is why no one can figure out where the doctrine came from or understand its significance: the mistranslation into Latin established the doctrine, and then after the mistranslation was “removed” (i.e. Latin was no longer the common language), the doctrine remained behind.

Christ—in Matthew 5:33-37—commanded us not to make vows but merely to answer truthfully in the simple affirmative: “I do.”

Any ritual that demands a sacred oath—a sacrament—that is more than simple affirmation of the truth is disobedience to Christ.

Yes, obeying Christ does really matter.

Accepting God’s plan for marriage is not difficult to understand: be faithful to your spouse if you have one, otherwise live a pure and chaste life. But the idea of the ‘Sacrament of Marriage’ carries with it a great amount of heavy baggage that does not belong.

Footnotes

[1] In Tertullian, “Prescriptions against Heretics“, Chapter 40, Tertullian compares pagan mysteries with Christian sacraments. Darius Jankiewicz, in “Sacramental Theology and Ecclesiastical Authority” notes:

[3] According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church #1623, “the spouses as ministers of Christ’s grace mutually confer upon each other the sacrament of Matrimony by expressing their consent before the Church.” A priest is involved in the administration of sacramental marriage and serves as a required witness, but he does not actually confer the sacrament itself.

Pingback: Soteriology

Pingback: Synopsis of Sacramental Marriage | Σ Frame

Pingback: What is Grace?

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 8: Interlude

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 9: Tertullian

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 17: Interlude

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 27: Interlude

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 31: Ambrose of Milan

Pingback: The Eucharist, Part 40: Conclusion

Pingback: Sacraments, Part 1: Divisions - Derek L. Ramsey