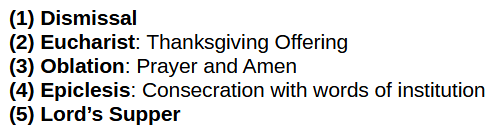

The original liturgy:

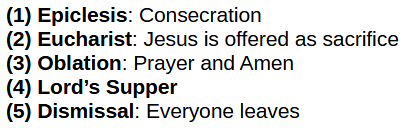

The Roman liturgy:

Let’s take a short break from the examination of the patristic era writers to look at the concept of the sacrifice and thanksgiving (eucharist).

The Eucharistic Sacrifice

The first mention of thanksgiving in the Bible is Leviticus 7 referring to the fellowship offering of thanksgiving, a sacrifice of bread or meat.

The thanksgiving was not restricted to only bread and wine.

Such an offering could be either a duty or by free will.

The next mention of thanksgiving is Leviticus 22:29…

…which again refers to the freewill thank offering. The thanksgiving offering consisted of both bread and meat which was not completely burned up, rather, it was consumed communally with the priest.

The thanksgiving was given corporately

There are three mentions in Nehemiah: 11:17 ties together thanksgiving and prayer. 12:8 associates thanksgiving with song. 12:26 ties together thanksgiving with praise.

There are various mentions of thanksgiving in the Psalms, but we’ll concern ourselves with two specifically. Psalm 116:17 refers again to the thanksgiving sacrifice. Psalm 107:21-22, utilizes Hebrew parallelism to associate the giving of thanks, the thanksgiving sacrifice, and the offering of praise.

The last two mentions in the OT are Amos 4:5 and Jonah 2:9. Amos describes the freewill thanksgiving offering and Jonah describes sacrificing shouts of thanksgiving praise.

These references cover over 50% of the OT references to thanksgiving: it is clear that the Hebrews understood bread, meat, thanksgiving, praise, and song as thanksgiving sacrifices freely offered.

The OT Law mandated 10% tithe offerings to support the priesthood and the poor. But, like the Widow’s Mite, the giving of the ‘tithe’ in the church is nonspecific and voluntary: it is a free will offering (e.g. Acts 2-6; 2 Corinthians 9:7) used to support those in need (e.g. 1 Corinthians 16:1-3).

We have called this the tithe offering throughout this series because it is directly based on the original tithe offering—supporting the clergy and those in need—but, strictly speaking, it isn’t a tithe as the amount isn’t predetermined and why they are called gifts. That is why the offering in the church is the thanksgiving offering. It is a free will sacrifice: by definition a eucharistic offering.

The point of the thanksgiving offering has never been the gift itself, but the thanksgiving behind the physical gift. Thus the Eucharist is referred both by the state of the heart and by the actions that come forth from that pure heart. You cannot truly have one without the other.

The thanksgiving is of a pure heart

True Sacrifice

Throughout this series, I’ve used the terms “thanksgiving”, “thanksgiving (eucharist) sacrifice,” and “thanksgiving offering” more-or-less interchangeably.[1] All thanksgiving and praise freely made to God is a sacrifice. In a meal, the giving of thanks for the food is the offering, not the food itself. This is true of the tithe. The tithe itself is merely the means by which one gives thanks to God, but it could also be praise, service (e.g. helping the poor), or singing hymns. All of these are typically offered to God formally by way of prayer and “Amen.”

This form of the thanksgiving [offering] that Christians offer is in fulfillment of the Old Testament:

Does this sound familiar? It should! So far in our series, we’ve already seen two patristic writers tie Malachi’s prophecy and the Eucharist together—Justin Martyr and Irenaeus of Lyons. Others include Ignatius, the Didache, Tertullian, Origen, Cyprian, Aphrahat, Athanasius, Lactantius, Hippolytus, and Eusebius. John the Revelator also referred to this…

…and Jesus spoke of its fulfillment with the Samaritan woman:

True worship was always sacrificial worship. For the Samaritans this was on Mount Gerizim. For the Jews it was in Jerusalem. But for Christians it is no longer blood sacrifices of animals, nor at any particular location: our sacrifice is now in Spirit and truth alone. This is why Jesus setup a Eucharist and why he commanded it of us. It is our thanksgiving [offering] to God.

When Jesus spoke to the Samaritan woman, he told her that his followers would worship in Spirit and truth now. Not after Christ’s last supper, crucifixion, death, resurrection, or ascension: now. The sacrificial worship that would be made in all places and in all nations began even then before Christ’s offering himself as the Paschal sacrifice.

The Paschal Sacrifice

At every Passover celebration, the Hebrews made a sacrifice of a lamb, called the Paschal Sacrifice. Jesus’ death took place during the Passover and Jesus himself took the place of the Passover lamb: he was the Paschal Sacrifice. In fact, he was the final Paschal sacrifice that God required.

For more information on the different types of sacrifices and offerings, see this article.

As we’ve seen in this series, the (1-3) sacrifice of the Eucharist is a separate observance from the (4-5) celebration of the Lord’s Supper, a remembrance of Christ being the Paschal sacrifice where he, on the cross, shed his body and blood for our sins so that death would permanently Pass Over us. The Lord’s Supper is memorial of the sacrifice of Jesus, the final paschal lamb, not the Passover sacrifice itself.

Since the Passover (or Paschal) and thanksgiving (or Eucharist) sacrifices are two completely different sacrifices, if Jesus’ death was a Paschal sacrifice, how then did a thanksgiving—Eucharist—sacrifice come to not only be associated with the Lord’s Supper (a remembrance of Jesus’ sacrifice), but to identify it?

The Lord’s Supper

During the Lord’s supper, Jesus made two eucharistic offerings—prayers of thanksgiving—before each element separately[2].

Jesus (2) eucharisted—gave thanks for—the bread and wine by a prayer of thanksgiving and then (4) consecrated the eucharisted—thanked for—food by saying the words of institution. And he did each one at a time.[2] In this way, the first Eucharist was Christ giving thanks for the meal before it was eaten, and only after that, consecrating it as his body and blood. The sacrifice was thanks to God for the meal.

Why did Jesus do this? Was there some greater spiritual significance to him giving thanks for the food?

The only eucharist—thanksgiving—[offering] during that final Passover meal before the crucifixion was Jesus’ prayers made before eating. But, the Old Testament Law mandated giving thanks after eating:

Yet the Pharisees instituted praying before eating, a tradition that Jesus adopted. You can find examples in Matthew 14:19-21, Matthew 15:34-37, Matthew 26:26-29, and Luke 24:30-31. Former Pharisee Paul adopted the same practice (Acts 27:35).

Nowhere in the NT is praying before a meal explicitly stated as a thanksgiving sacrifice. Thanksgiving, yes, but not a sacrifice. It is a deduction from the Old Testament that the giving of thanks in prayer is a sacrifice. Moreover, the thanksgiving [offering] was the prayer Jesus made and that this prayer was neither unique nor specific to the Lord’s Supper, because he prayed before every meal.

The prayers Jesus made before eating were his thanksgiving.

…and…

Jesus’ thanksgiving—eucharist—was not unique to the Lord’s Supper.

The tradition of praying before eating has no direct causal link to Jesus dying on a cross (i.e. the Paschal sacrifice), as the tradition of praying before eating has no direct causal link to the Passover at all (let alone the meal specifically). The freewill thanksgiving sacrifice was a specific sacrifice in Mosaic Law that was unrelated to the Paschal sacrifice: no Hebrew would confuse the two.

So I ask again, how did ‘eucharist’ come to be applied to the Lord’s Supper, specifically the bread and wine?

After a long time had passed, the Lord’s Supper (of consecrated bread and wine) came to be called the Eucharist because the bread and wine used for the Supper were taken from the Eucharistic tithe offering (unconsecrated bread, wine, oil, cheese, etc…). Many of the patristics we examine throughout this series testified that the unconsecrated Eucharist—the tithe—preceded the consecrated meal. From these writings, there is evidence that the Supper came to be called the Eucharist because without the Eucharist, there would be no elements to consecrate by speaking the words of initiation and then to consume.

In summary, how and when did the Lord’s Supper—in particular the bread and wine—take on the label of Eucharist? All existing evidence prior to the mid-4th-century suggests that it came to bear the name because the bread and wine came out of the eucharistic offering. It was, quite literally, (part of) the thanksgiving [offering]. The eucharisted—”thanksed”—food, even once it was consecrated, remained eucharisted food.

The Paschal Eucharist

The Roman liturgy conflates the thanksgiving sacrifice—the Eucharist—with the Paschal sacrifice, as if they were the same thing: a Paschal Eucharist. It is in this way that Christ’s “real” body and blood are offered both as thanksgiving (i.e. eucharist) and as a living sacrifice to God at every Mass (i.e. a Paschal sacrifice) for the remission of sin. But this conflation exists nowhere in the first 300 years of the church. The innovation only became established much later in the medieval era.

This conflation has led to some extremely absurd claims by some Roman Catholics trying to wrap their heads around the absurdity of the Roman liturgy. For example, some have stated that Christ’s body and blood were already the Paschal sacrifice at the Last Supper[3]: Jesus offered himself to his disciples, so it must have been a sacrifice, and, Jesus used the words of institution, so his crucified[4] body must have been literally present in the bread and wine that they consumed. This logically (and paradoxically[5]) implies that Jesus didn’t even have to die on the cross.[6] In other words, the real literal sacrifice for the forgiveness of sins was the offering at the Lord’s Supper, while the death on the cross and resurrection was symbolic of the offering of the body and blood in the bread and wine.

I cannot stress hard enough that this is a perfectly logical explanation for the Roman Mass sacrifice.[7] It is absurd only from a biblical standpoint, not as a matter of Roman doctrine. If moral inversion is the spirit of the age, then the inversion of literal and figurative with respect to Christ’s body and blood perfectly illustrates it.

In case you think that this is a fringe view that does not represent the Roman Catholic Church—rather than the necessary logical conclusion—consider this account from the trial of Hugh Latimer, who was burned at the stake. They were arguing over the meaning of John 6, the same one that we reference throughout this series.

Latimer.— “I have but one word to say, ‘the sacramental bread’ is called a propitiation, because it is a sacrament of the propitiation. What is your vocation?”

Weston.— “My vocation is at this time to dispute; otherwise I am a priest, and my vocation is to offer.”

Latimer.— “Where have you your authority given you to offer?”

Weston.— “Hoc facite, Do this: for facite [English: ‘do ye’] in that place, is taken for offerte, that is, offer you.”

Latimer.— “Is facere nothing but ‘to sacrifice?’ Why, then, no man must receive the sacrament but priests only : For there may none other offer but priests.—Ergo, there may none receive but priests.”

Weston.— “Your argument is to be denied.”

Latimer.— “Did Christ then offer himself at his supper?”

Pie.— “Yea, he offered himself for the whole world.”

Latimer.— “Then, if this word ‘do ye’ [Latin: facite], signify ‘sacrifice ye’ [Latin: sacrificare], it followeth, as I said, that none but priests only ought to receive the sacrament, to whom it is only lawful to sacrifice: and where find you that, I pray you?”

Weston.— “Forty years agone, whither could you have gone to have found your doctrine?”

Latimer.— “The more cause we have to thank God, that hath now sent the light into the world.”

Citation: John Foxe, “The Protestation of Dr. Hugh Latimer.” Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Book II. §XVI

Latimer won the argument by his appeal to scripture, by pointing out a logical discrepancy. Latimer understood that the sacraments and the priesthood were inextricably linked, reasoning from the Roman Catholic position to a logical contradiction.

So how did his opponent respond? He simply dismissed it without engaging with the argument and stated (paraphrasing) “Your doctrine is a modern one that didn’t exist 40 years ago, before Luther.” This is precisely the kind of dismissive “argument” that one can see on the internet today from those who don’t want to consider other biblical viewpoints.

But, it turns out as we’ve examined in this series, Latimer’s argument was not a modern one. Latimer was burned at the stake over a lie perpetuated by the Roman Catholic Church, but not before it became clear that the Roman Catholic Church believes that the real sacrifice of Christ was at the Last Supper.

Nowhere in the Old Testament were the thanksgiving and Paschal sacrifices equated. Nowhere in the New Testament were the thanksgiving and Paschal sacrifices equated. Nowhere in the first 300 years of the church have the thanksgiving and Paschal sacrifices been treated equally.[8]

It is no wonder that the the liturgy of the Roman Catholic Mass opens with this:

Roman Catholicism has taken what was plain and easy to understand and turned it into confusion and shrouded it in mystery.

Instead, let’s keep it simple and clear:

The Eucharist is not the Lord’s Supper

The Lord’s Supper is not a sacrifice

If that’s all you get out of this series, I have done my job. But, if you really want to “complicate” it, try this too:

The Eucharist is a thanksgiving offering, not a Passover sacrifice

Footnotes

[1] Thanks to FishEaters in “The Eucharist” for this 5th century Jewish Midrash on Leviticus 7:11-12:

This is the law of the peace offering that one sacrifices to the Lord.” That is what the verse says: “One who slaughters a thanks offering honors Me” (Psalms 50:23). It is not written here “One who slaughters a sin offering,” or “one who slaughters a guilt offering,” but rather, “one who slaughters a thanks offering.” Why? A sin offering comes due to a sin and a guilt offering comes due to a sin. A thanks offering does not come due to a sin, “if he sacrifices it as a thanks offering.”

…

Rabbi Pinḥas, Rabbi Levi, and Rabbi Yoḥanan in the name of Rabbi Menaḥem of Galya: In the future, all the offerings will be abolished but the thanks offering will not be abolished. All the prayers will be abolished, but the thanksgiving [prayer] will not be abolished. That is what is written:

this is the thanksgiving [prayer];

this is the thanks offering. Likewise, David says:

Toda is not written here, but todot, thanksgiving and a thanks offering.

Citation: “Vayikra Rabbah 9.” The Sefria Midrash Rabbah (2022)

As we saw in our analysis above, according to the Old Testament, when Christ came he abolished all sacrifices except for the Eucharist. Notice, especially, that it is simply called the “thanksgiving”, whether it was the thanksgiving prayer or the thanks offering. Throughout the Bible and the early writers of the church, this would remain the case.

In many cases I refer to the “thanksgiving prayer” or the “eucharist sacrifice”, because I am trying to avoid confusion from only saying “thanksgiving,” even though this is what the Bible did. The “thanksgiving” does not have be qualified by “sacrifice”, “offering”, “gift”, “prayer”, “hymn”, or anything else, although it is common practice to do so.

[2] Separately. Since the ruling by the Council of Constance in 1415, the Roman Catholic laity needed only to receive the bread. The doctrine of concomitance says that Christ is indivisible and no part of Christ’s substance is divisible. Christ’s body cannot be separated from his blood, therefore Christ must be fully present in each individual element. Roman Catholics also believe that invoking the consecratory phrases “this is my body” and “this is my blood” is an offering of sacrifice. But, since Christ offered them separately, and they were consumed separately, Christ himself was dividing that which was indivisible by offering separate sacrifices of himself, a logical contradiction of the doctrine. More recently, the Second Vatican Council in 1960 reauthorized the reception by the laity of both.

[3] To wit:

…

Sacrifice is not the act of killing the victim but of offering it to God. That is the big mistake of the Protestant over emphasis on the cross to the detriment of other aspects of Christ’s work.

Citation: Art Sippo, “Q&A on the Sacraments.” Catholic Legate.

Protestants reject that propitiation—or appeasement—at the hands of an angry God is required for the remission of sins: only faith in Christ through the power of the cross. The Roman Catholic view logically denies the power of the cross.

[4] The bread has come alive on a number of occasions and are well-documented by Roman Catholics themselves. In particular, on August 18, 1996 The Host turned into bloody heart muscle, which was verified by eyewitnesses and medical tests. The blind medical tests showed that the muscle had come from a body that had suffered a violent death, consistent with death by crucifixion. This Eucharistic miracle was personally verified by the current sitting Pope.

[5] In the philosophy and mathematics of time travel, going forward in time never creates a paradox, because causality remains unaffected. Thus the Old Testament Patriarchs could see forward in anticipation of Christ and his sacrifice. But going backward in time creates paradoxes because it breaks causality: cause and effect are reversed. If Christ’s already crucified flesh was present in the bread and wine at the Last Supper, this is a logical paradox. This Roman Catholic metaphysical view of time necessarily requires that effects can precede causes.

[6] For Jesus to offer himself as a Paschal sacrifice at the last supper, it logically implies that Jesus didn’t actually have to physically die on the cross in order for his disciples to receive the propitiatory sacrifice for the remission of sins. They must have received propitiation at that very moment, whether or not Christ actually went on to die on the cross, or else it would have had no efficacy at all at that moment. The following does not logically follow:

Citation: Art Sippo, “Q&A on the Sacraments.” Catholic Legate.

Do you see the logical flaws in the analogy and the biblical errors? The Passover account is given in Exodus 12. In the original Passover, the Paschal sacrifice was a bloody one done in anticipation of avoiding the death of the First Born that same day.

First, the blood of the lamb had to be smeared on the door frame for death to pass over. Thus, the Paschal sacrifice could not have been bloodless, as Roman Catholics claim the sacrifice of the Lord’s Supper was. Only the blood of the Paschal sacrifice caused death to pass over. Only the blood could save. A bloodless sacrifice could not be propitiatory.

Second, in the Passover, the Lamb was sacrificed for its blood so that no firstborn died. It was an either-or situation. Either the lamb was killed and blood smeared or the firstborn was killed. One or the other. Not both. By the Paschal analogy, if Christ offered himself as the Paschal lamb at the Last Supper, then no firstborn had to die. If Jesus—the firstborn—was sacrificed as the Paschal sacrifice at the Lord’s Supper, his death on the cross was not necessary. So too, if his death was still necessary on the cross, then he could not already have been sacrificed as the Paschal sacrifice.

Third, the lamb was killed on the same night that the firstborn was killed. It was not the next day or even in the daytime of that same day. Jesus was crucified and died on the day after the Lord’s Supper.

Fourth, the Last Supper did not take place on the day of the Passover. He and the disciples celebrated the meal a day early, so that Christ could die on the day that the Passover lamb was supposed to be sacrificed, in fulfillment of the law and taking its place. (There is some confusion in modern minds because there were multiple Sabbath days that week, but this is a topic for another day)

A bloodless thanksgiving could not—in any way—have stood in the place of the Paschal sacrifice on the cross. Just as Roman Catholicism errs when it combines the Eucharist with the Lord’s Supper, so too when the thanksgiving offering is combined with the Paschal sacrifice.

[7] Most do not consider the logic of their beliefs. Absurdities are either considered and accepted anyway, or else they are ignored through an act of blind faith. In this way, blind faith becomes an act of self-deception.

[8] But, if I had been alive with Latimer, I would have been burned at the stake for what I’ve said in this series. The only difference is now the Roman Catholics who read this blog can’t murder me for saying it. But, in the past, they absolutely would have if they could have because they actually did burn people for this very thing. And many Roman Catholics have said that they wish that they could have a Christian Nationalism ruled by the Roman Catholic Church. In their heart of heart, they’d see me dead. Not personally, of course, because no one wants to do the dirty work themselves, but rather at the hands of their Church, which absolutely would do so again if it could.