The original liturgy:

The Roman liturgy:

Gregory of Nyssa

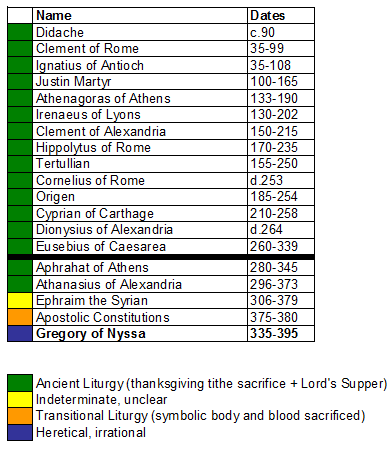

In Part 18: Athansius of Alexandria we saw how in 373, the church in Alexandria still held to the ancient liturgy, clearly separating the (1-3) sacrifice of thanksgiving from the (4-5) celebration of the Lord’s Supper. But in Part 19: Ephraim the Syrian, we saw how in that same year, 373, in another corner of the Mediterranean in Asia Minor, there were hints of a change to the ancient liturgy. In Part 16: Apostolic Constitutions, written between 375 and 380 in Asia Minor, we had begun to see a major shift in liturgy away from its ancient form into the Roman liturgical form.

What was so special about the late 4th century, beginning ~370AD—300 years after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem—until ~400AD? We discussed in Part 17: Interlude the historical events corresponding to the rise of Roman Catholicism during that period, how the political and religious changes were intertwined, and how this is visible in the writers we are examining.

In the midst of this time frame is Gregory of Nyssa, who was Bishop of Nyssa for all but two years from 372 to 395. Nyssa was in Cappadocia in the heart of Asia Minor, near where the influential Apostolic Constitutions was supposedly written between 375 and 380.

As we examine the works of Gregory of Nyssa, we will find something amazing and unprecedented to this point in liturgical history. But before we get to that, let’s look at the quotation from FishEaters, and see what we find:

…

In the plan of His grace He spreads Himself to every believer by means of that Flesh, the substance of which is from wine and bread, blending Himself with the bodies of believers, so that by this union with the Immortal, man, too, may become a participant in incorruption.

Citation: Gregory of Nyssa, ca. A.D. 335 – 394 The Great Cathechism Part III: The Sacraments, Chapter 37

It is curious that FishEaters selected the first quotation. It does not seem to describe a Roman liturgy at all.

First, the consecrated bread is made into the body of God as “the Word” and “divine strength.” These are plainly symbolic.

Second, the substance—not merely the appearance—of the consecrated bread is just bread!

Third, the bread becomes the body of the Word by the words of institution, not by being eaten. Nowhere have we seen the claim that being eaten consecrates the bread, but rather quite the opposite.

In total, this is not a very Roman liturgy. But what about the second quotation?

Again, Gregory says that the substance of the flesh is from bread and wine. This is, again, curious. According to the Roman liturgy, the bread is only bread in appearance and the substance of the bread and wine is supposed to be the flesh. Gregory almost seems to be suggesting that it is the other way around: that the bread and wine are the substance.

What does he mean by the bread blending the Immortal and Incorruptible into us. This could suggest that he means that the bread is literally the flesh of the resurrected Christ while it is also still literally bread. Or it could mean that the bread has a physical (bread) and spiritual (body) component. Since this is what we found in Ephraim and Apostolic Constitutions, this seems more likely, but it’s just speculation.

In this quote, I don’t see either the ancient liturgy or the Roman liturgy. It is unclear and confusing.

I’m not the only one who is confused. One Orthodox Christian writes:

As Gregory continues the work, we can see his universalist statements are often qualified so as to mitigate against their universal applicability to each individual. In Chapter 37, he writes concerning the salvific quality of the sacrament of the Eucharist:

[..]Why not just say all of mankind is vivified? Why point out that this is true only among “every believer” in whom “there is Faith?” Where is the merit of the unbeliever? Where is their union with Christ? How are they vivified by a direct participation in Divine energy by consuming God’s flesh and blood? Why warn that those who are baptized with incorrect faith are not saved?

Citation: Craig Truglia, “Questioning Gregory of Nyssa’s Universalism: The Great Catechism.” (2020)

Truglia sees this same quote (omitted above for brevity) as describing a salvific quality of the Eucharist (uh, sure? no? maybe?), but he finds the argument he is making confusing and unnecessary. Frankly, it seems like Gregory is not thinking logically about this at all.

In my research I see plenty of people quoting this, but I don’t see many people commenting on it. Even Joshua Charles, Roman Catholic apologist who is a former Protestant, merely repeats this quote, without commentary, as evidence of the Real Presence of Christ. Again, maybe he is right, but who actually knows? The Melkite Catholic Eparchy of Newton has a single sentence commentary:

This is not very helpful. If anyone has a better explanation, I’m all ears.

Short of simply assuming that Gregory is talking about the Roman liturgy, I don’t why a Roman Catholic would even want to cite any of these quotes. But I promised an amazing and unprecedented commentary by Gregory, so let’s do that instead.

In Part 8: Interlude, we showed how in both modern times and during the Reformation the Roman Catholic church believed that Jesus offered himself as a sacrifice at the Lord’s Supper. There we noted that for this to work logically—according to Roman Catholic doctrine—Jesus had to have offered his literal, crucified flesh before he had actually been crucified. This is a metaphysical paradox of causality, where effect precedes cause (i.e. backwards time travel). But at the time, I had not shown how far back this viewpoint goes, nor where this view originated. That day has come. Behold:

For the body of the victim would not be suitable for eating if it were still alive. So when he made his disciples share in eating his body and drinking his blood, already in secret by the power of the one who ordained the mystery his body had been ineffably and invisibly sacrificed and his soul was in those regions [of the grave] in which the authority of the ordainer had stored it, traversing that place in the “Heart” along with the divine power infusing it.

…

He offered Himself for us, Victim and Sacrifice, and Priest as well, ‘Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.’ When did He do this? When He made His own Body food and His own Blood drink for His disciples; for this much is clear enough to anyone, that sheep cannot be eaten by a man unless its being eaten be preceded by its being slaughtered. This giving of His own Body to His disciples for eating clearly indicates that the sacrifice of the Lamb has now been completed.

Citation: Gregory of Nyssa, “On the Space of Three Days” (382)

Translation:

- S.G. Hall (De tridui spatio 287.21-288.8)

- William A. Jurgens, “The Faith of the Early Fathers.” 2:59 (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1979).

Unable to find three days when Jesus was dead and in the ground from the time available from the crucifixion until Easter morning, Nyssa concluded that Jesus was really, actually, fully dead on Thursday and that he had really, actually, fully sacrificed himself at the Lord’s Supper, thus solving the problem of the three days.

Jesus was crucified before he was crucified, dead before he died, buried before he was buried. Time travel.

On one hand, Gregory thought Jesus was in the grave while serving his own crucified and buried dead flesh as food for his disciples which was literally present in the bread and wine even as he was actively sacrificing himself.

On the other hand, Gregory has been used to support the idea that the crucified Christ’s flesh and blood were literally present in the bread and wine of the Last Supper before he was crucified.

Both of these are paradoxes. If only one of these seems crazy to you, the problem may well be an intellectual one: cognitive dissonance. If only Gregory sounds crazy, congratulations, you are a Roman Catholic.

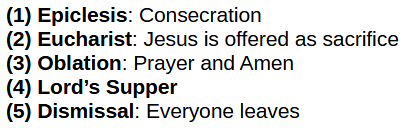

Apostolic Constitutions—between 375 and 380—eliminated most of the thanksgiving offering while combining the Eucharist into the Lord’s Supper, but still treated the elements as symbolic, even after the words of institutions. Then, in 382, Gregory wrote that the bread and wine were literally his crucified flesh which Christ himself was offering. This was all that future history would need to eventually construct the Roman liturgy. Who cares that Gregory said that Jesus was actually dead and in the grave at the time of the Lord’s Supper! Roman Catholicism could fix that minor error: keeping the literal sacrifice, but don’t have it be dead.

This, notably, doesn’t fix the time-travel paradox. I’m not the only one who thinks so:

Such are the inventive and fanciful origins of the sacrifice of the Mass—Gregory of Nyssa attempting to bend the space-time continuum to get the math to work out. Until the time of Gregory, nobody had ever proposed that Jesus had sacrificed Himself on Thursday night. But since then, Rome has never ceased to insist that everyone—from the apostolic era onward—had always recognized that Thursday night was the night Jesus offered His sacrifice for our sins when He gave bread and wine to his apostles.

…

The only option left to them is the option exercised by Gregory of Nyssa: tamper with the space-time continuum. [..] That is the only evidence available to them on the Thursday night sacrifice.

Citation: Timothy F. Kauffman, “Melito’s Sacrifice.” Out of His Mouth (2015)

..and…

Citation: Timothy F. Kauffman, “Their Praise Was Their Sacrifice, Part 8.” Out of His Mouth (2015)

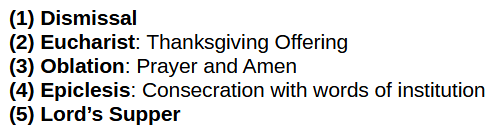

Recall our discussion of Malachi’s prophecy in Part 8: Interlude, how it was fulfilled in (2-3) the church’s thanksgiving offering—eucharist—of the sacrifice of prayer, praise, hymns, service, and the giving of tithes. So far we’ve seen how Jesus, John, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Origen, Cyprian, Aphrahat, Athanasius, and Eusebius had all spoken as if with one voice.

But, beginning around 370AD, it would develop into a sacrifice of bread and wine. Gone was the testimony of the many voices that came before it. That history we examine would be twisted and turned into a great lie:

All the Holy Popes, and Fathers, and Councils of the primitive ages, teach that the mass is the self same sacrifice of bread and wine that had been instituted by our Saviour; whilst the histories and annals of all countries, not excepting England herself, declare that the Holy Mass, but no other sacrifice, came down to them as a part and parcel of Christianity, from the apostolic age. Citation: “Douay Catechism.” Question 682. (1649)

So great is this lie that it has deceived the world.

Latimer.— “Did Christ then offer himself at his supper?”

Pie.— “Yea, he offered himself for the whole world.”

Latimer.— “Then, if this word ‘do ye’ [Latin: facite], signify ‘sacrifice ye’ [Latin: sacrificare], it followeth, as I said, that none but priests only ought to receive the sacrament, to whom it is only lawful to sacrifice: and where find you that, I pray you?”

Weston.— “Forty years agone, whither could you have gone to have found your doctrine?”

Latimer.— “The more cause we have to thank God, that hath now sent the light into the world.”

Citation: John Foxe, “The Protestation of Dr. Hugh Latimer.” Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Book II. §XVI

At the dawn of the Reformation, those who read scripture for themselves realized that the Roman liturgy was not found in scripture. But, in response to the accusation that his doctrine was new, all Latimer could say is that God had simply revealed it. Such was the state of affairs before modern biblical scholarship, when widespread access to books, manuscripts, translators and translations, computers, and the internet led to an explosive access to historical documents. A month-long series like this one might have taken a lifetime or more to complete.

Now, were we the ones ready to be burned at the stake, we would be equipped to answer Weston’s challenge much differently:

And we might even say: