The original liturgy:

The Roman liturgy:

Dionysius of Alexandria (d.264)

In this seventh book of the Church History, the great bishop of Alexandria, Dionysius, shall again assist us by his own words; relating the several affairs of his time in the epistles which he has left. I will begin with them.

Citation: Eusebius, “Church History.” Book 7

But I did not dare to do this; and said that his long communion was sufficient for this. For I should not dare to renew from the beginning one who had heard the giving of thanks [εὐχαριστίας] and joined in repeating the Amen; who had stood by the table and had stretched forth his hands to receive the blessed food [τῆς ἁγίας τροφῆς]; and who had received it, and partaken for a long while of the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ. But I exhorted him to be of good courage, and to approach the partaking of the saints with firm faith and good hope.

Citation: Eusebius, “Church History.” Book 7. §9¶4

Dionysius had a man in his congregation who had been taking the eucharist with the congregation for a long time, but he hadn’t received a proper Christian baptism first, having been baptized initially by heretics. This created quite a conundrum! Should he be denied communion until he could be “renewed” (i.e. rebaptized) properly, or should he be treated as if his faith and long participation in communion made his illegitimate baptism of no consequence? In the end the latter was chosen, but there are a few things to note.

First, this shows that the Dismissal was still practiced after 300 years, because Dionysius would never have knowingly allowed a participant who hadn’t been properly baptized into Christianity. This was, after all, the reason for his dilemma.

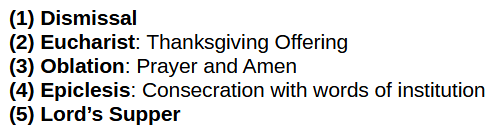

Second, Dionysius describes a (2) Eucharist followed by (3) a corporate Amen. This is the ancient liturgy that we have seen throughout this series.

Now let’s consider the use of the term “blessed food” here. Throughout this series the English translators have typically used the term blessed to refer to the (4) consecrated bread and wine. But Dionysius is clearly referring to the Eucharist, the tithe. What gives?

The Greek word used for “blessed” is properly translated as “holy,” of which the tithe is so described because it has been set aside as an offering and sacrifice to God. The word sacrifice itself means “to make sacred” or “to make holy.” By definition, if it is a sacrifice acceptable to God, it is holy.

For example, in The Didache, the earliest known reference to the Eucharist, the offered food of the thanksgiving is called holy:

…But let no one eat or drink of your Thanksgiving (Eucharist), but they who have been baptized into the name of the Lord; for concerning this also the Lord has said,

Citation: “The Didache.” Chapter 9

The quotation from Matthew makes it clear that the tithe is holy and being holy does not require or imply that it is consecrated. After all, no words of initiation are spoken.

But, this has not stopped Roman Catholic translators from trying to put a spin on the text to make Dionysius say something he never said in order to insert the Roman liturgy where it otherwise is not:

Citation: Timothy F. Kauffman, “Collapse of the Eucharist, Part 4.” Out of His Mouth (2020)

Perhaps the most interesting acknowledgment here that J.P. Migne makes is not his linking of the “Amen” in Justin Martyr with the “Amen” in Dionysius, but that he links it to the “Amen” to the Apostle Paul himself:

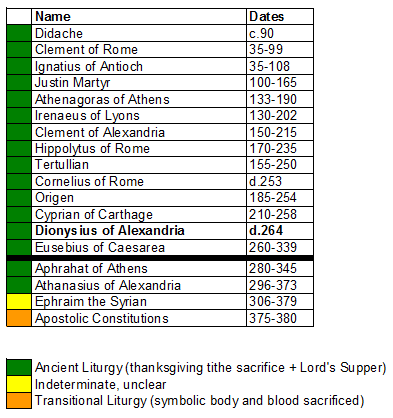

In the series so far, 8 out of 17 sources that we’ve examined so far, almost half—Dionysius, Cornelius, Athanasius, Hippolytus, Tertullian, Irenaeus, Justin Martyr, The Didache—mention the corporate “Amen” that separates the Unconsecrated Sacrificed Eucharist that is offered from the Consecrated Unsacrificed elements eaten at the Lord’s Supper.

But I’ve found something very curious: The “Amen” is hardly ever (if at all) discussed in detail. The authors simply do not expound on why there is an Amen there, let alone why it is corporate: it just is. It’s almost always mentioned incidentally. And for at least ~320 years after Christ’s ascension, the Amen survives without modification in the ancient liturgy, despite no one writing about why it is there or arguing over its inclusion.

I suspect that even if all you read were the non-apostolic writers up until 350AD and nothing else, you wouldn’t have much idea why that “Amen” is mentioned in the context of the Eucharist. You probably wouldn’t even have noticed its presence, even though it is apostolic! You’d probably conclude, as most people do, that “all prayers end with an ‘Amen’, so what’s so special about this one?” I’m willing to bet that few Christians living today—whether Anabaptist, Protestant, Orthodox, or Roman Catholic—know about the significance of the “Amen” to the Eucharistic liturgy, how it separates the two liturgical acts.

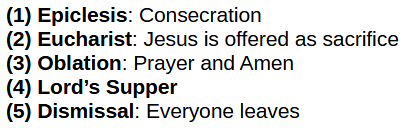

I suspect also that this lack of emphasis made it easier for Roman Catholicism to eventually shatter that Amen so the first liturgical act (Eucharist) could be merged with the second liturgical act (Lord’s Supper) into its idolatrous bastard Roman offspring (Mass Sacrifice). And so it is quite the surprise to see a Roman Catholic of Migne’s stature simply acknowledging, even grudgingly, that the “Amen” in Dionysius is apostolic!

But I’m also not surprised that a Roman Catholic scholar would talk himself into interpreting it through a Roman Catholic lens, after all, if he did not do so logic would demand that he no longer be a Roman Catholic anymore. So the fact that he didn’t deconvert in the face of the evidence tells you precisely what his motives were in interpreting the passage.