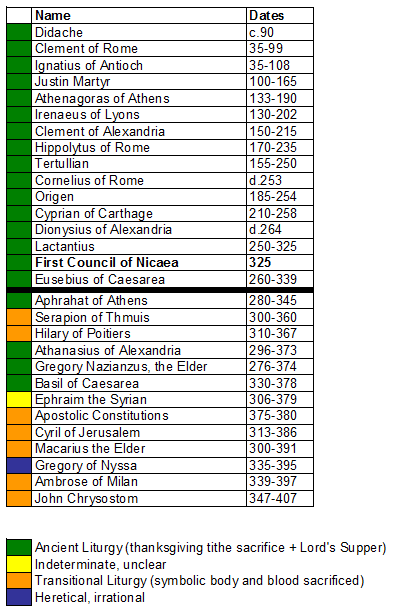

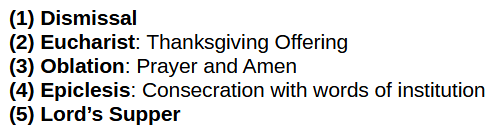

The original liturgy:

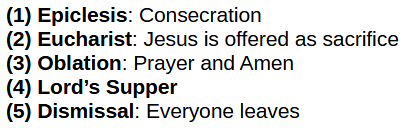

The Roman liturgy:

First Council of Nicaea

“Forasmuch as there are certain persons who kneel on the Lord’s Day and in the days of Pentecost, therefore, to the intent that all things may be uniformly observed everywhere (in every parish), it seems good to the holy Synod that prayer be made to God standing.” Citation: Council of Nicaea, Canon XX (325AD)

Throughout this series I’ve mentioned off and on that the early church banned kneeling. Besides the Council of Nicaea, we have a few other ancient references that make the same attestation:

Citation: Irenaeus of Lyons, “Fragment 7.” §7 (c.180)

Citation: Tertullian, “The Chaplet.” §3 (c.235)

But Roman Catholics are required to kneel, in direct violation with the apostolic teaching.

Citation: Pope Pius XII, “Mediator Dei: On the Sacred Liturgy.” §24. Vatican. (1947)

“It may well be that kneeling is alien to modern culture — insofar as it is a culture, for this culture has turned away from the faith and no longer knows the one before whom kneeling is the right, indeed the intrinsically necessary gesture. The man who learns to believe learns also to kneel, and a faith or a liturgy no longer familiar with kneeling would be sick at the core. Where it has been lost, kneeling must be rediscovered, so that, in our prayer, we remain in fellowship with the apostles and martyrs, in fellowship with the whole cosmos, indeed in union with Jesus Christ Himself.”

Citation: Pope Benedict XVI, “The Spirit of the Liturgy.”

- an attitude

- a gesture: involving, like prostration, a profession of dependence or helplessness, and therefore very naturally adopted for praying and for worship in general.

…

To kneel while praying is now usual among Christians. Under the Old Law the practice was otherwise. In the Jewish Church it was the rule to pray standing, except in time of mourning (Scudamore, Notit. Eucharist., 182).

…

It is noteworthy that, early in the sixth century, St. Benedict (Reg., c. l) enjoins upon his monks that when absent from choir, and therefore compelled to recite the Divine Office as a private prayer, they should not stand as when in choir, but kneel throughout. That, in our time, the Church accepts kneeling as the more fitting attitude for private prayer is evinced by such rules as the Missal rubric directing that, save for a momentary rising while the Gospel is being read, all present kneel from the beginning to the end of a low Mass; and by the recent decrees requiring that the celebrant recite kneeling the prayers (though they include collects which, liturgically, postulate a standing posture) prescribed by Leo XIII to be said after Mass it is well, however, to bear in mind that there is no real obligation to kneel during private prayer.

…

Turning now to the liturgical prayer of the Christian Church, it is very evident that standing, not kneeling, is the correct posture for those taking part in it. [..] The practice of kneeling during the Consecration was introduced during the Middle Ages, and is in relation with the Elevation which originated in the same period. [..] There are, nevertheless, certain liturgical prayers to kneel during which is obligatory, the reason being that kneeling is the posture especially appropriate to the supplications of penitents, and is a characteristic attitude of humble entreaty in general. Hence, litanies are chanted, kneeling, unless (which in ancient times was deemed even more fitting) they can be gone through by a procession of mourners. So, too, public penitents knelt during such portions of the liturgy as they were allowed to assist at. The modern practice of Solemn Exposition of the Blessed Sacrament for public adoration has naturally led to more frequent and more continuous kneeling in church than formerly. Thus, at a Benediction service it is obligatory to kneel from beginning to end of the function, except during the chant of the Te Deum and like hymns of Praise.

…

The canon thus forbids kneeling on Sundays; but (and this is carefully to be noted) does not enjoin kneeling on other days. The distinction indicated of days and seasons is very probably of Apostolic origin.

Citation: Frederick Thomas Bergh, “Genuflexion.” Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol 6. (1909)

Why do Catholics kneel during their services? This seems unnecessary. Why not just sit still and listen to the preaching of God’s word?

Answer: If you attend a Catholic Mass you will see the first part of it consists of reading and preaching; we stand for the Gospel, but we sit for the other readings and for the preaching. But the Mass is more than just reading and preaching. The Mass is a sacrifice, and there are times–especially in the last part–when the faithful pray on their knees. Kneeling shows our humility before God.

Your question is a surprise because you probably should be asking yourself why you don’t kneel in your Protestant services. Scripture suggests you should. In Ephesians 3:14 Paul says, “I kneel before the Father,” and in Acts 9:40 Peter “knelt down and prayed.” The Catholic habit of kneeling is consistent with Scripture and is another manifestation of the continuity between the Church of the first century and the Catholic Church of today.

Citation: Catholic Answers Staff, “Why Do Catholics Kneel?“

For Roman Catholics, kneeling is one of the most distinctive physical gestures of prayer during the celebration of Mass. In fact, for many centuries the lay faithful of the Roman Rite would kneel for almost the entire duration of Mass.

…

For these reasons the Roman Rite instructs the faithful to kneel during Mass specifically when Jesus is made present on the altar. According to the General Instruction of the Roman Missal, “In the Dioceses of the United States of America, [the faithful] should kneel beginning after the singing or recitation of the Sanctus (Holy, Holy, Holy) until after the Amen of the Eucharistic Prayer.”

This physical posture is meant to express a spiritual attitude of adoration before the triune God, truly and substantially present in the Holy Eucharist. It is an act of humility, recognizing our own littleness before the Creator of the world. The act of kneeling prepares our hearts to receive God within our souls, striking down our pride with a physical reminder of what our soul should be like spiritually.

In this way, kneeling in the context of the Roman liturgy is directly tied to Jesus’ presence in the Eucharist.

While not officially part of the Rite, it is a common custom in some churches to maintain a kneeling posture until the consecrated hosts are placed back within the tabernacle.

Kneeling during Mass is an ancient posture, one that expresses a deep spiritual truth that is connected to the Real Presence of Jesus on the altar.

Citation: CatholicTT, “Why do Roman Catholics kneel at Mass?“

Kneeling in the Mass is not, in fact, an ancient practice. If there had been a Sacrifice of the Mass in the first 300 years of the church (there was not), then kneeling would not have been banned. The Apostolic practice—privilege—was to stand.

Kneeling was added to the liturgy only after Christ’s body was offered as a sacrifice starting in the late 4th century. This change represents far more than a superficial change to the liturgy. It is an alteration of its very purpose.

Of particular note is that kneeling during the Mass—which should be forbidden entirely—is most tightly related to the adoration and worship of the bread.