This is part of a series on Roman Catholicism and the eucharist. See this index.

I have received a number of standard objections to the claim that “the eucharist in the early church was the tithe offering.” Here are a couple of the most common ones:

- Then the church was wrong for 1000+ years

- None of the early writers identified the eucharist as a tithe

Today we will discuss this latter objection. We’ll save the other for another day.

What is the Tithe?

Naturally, I do not accept the objection’s framing at face value. The Old Testament, the New Testament, and the early writers all describe a thanksgiving (eucharist) offering of tithes in various ways. To be a thanksgiving offering—a eucharist—was to include a tithe both explicitly and implicitly. There was no need for any early writer to use the term “tithe” at all.

But, there is another simple explanation for why the early church didn’t use the term “tithe” interchangeably with the word “thanksgiving” (eucharist): they didn’t use the term “tithe” in precisely the way that we use the term today.

The nature of the ancient thank offering—what the church called the eucharist—is well-defined. After all, under the Law,

Every thanksgiving offering had to include a tithe.[1]

The problem we face is not whether the thanksgiving (eucharist) was a tithe, but a secondary concern of how we deal with the semantic confusion caused from translating words like “eucharist” and “tithe” between multiple different languages (Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and English). It is, figuratively speaking, a logistical problem, not a theological one.

In the Old Testament the tithe usually refers to giving away a literal 10% of something and keeping the remaining 90%. This, of course, remains one of the accepted meanings for the English word tithe (as in definition #1), but the English term carries a broader, more generalized meaning as well (as in definition #3). This ambiguity is why some churches refer to all the gifts collectively as “tithes and offerings”[1] or else simply call the giving of gifts “the offertory.” The word tithe, along with decimate, no longer necessitate the previously strict historical numerical connotation.

One of the primary purposes of the Old Testament tithes was to provide for those in need: the priests, the poor, widows, etc. It was a kind of tax (as in definition #4). The reason the tithe was 10% is because the giving of tithes was a not voluntary. It was a fixed observance. The giving and the amount given were regulated and mandatory.

But with the cessation of sacrifices (as we’ll shortly see below), the traditional sacrificial tithe ended. It was replaced with a bloodless version of the Old Testament freewill thanksgiving peace offering, in which gifts were given freely according to the giver.

Is this a “tithe” or should we call it something else? Well, the church can—and does—call it a tithe, even though the church does not mandate that givers give 10%. Since Jesus, the tithe of the New Testament hasn’t been the tithe of the Old Testament. The purpose of the tithe remains the same—to support those in need—but the nature of, and ultimate reason for, the giving itself shifted focus. Instead of the tithe being—arguably—primarily about social supports, giving in the church to help others is now about being grateful to and thanking God.

So if you look to the early writers to find them calling the thanksgiving (eucharist) offering a tithe (in the Old Testament sense or as in definition #1), you will see no such quotes. That’s because the early church’s tithe (as in definition #3) was not the tithe (as in definition #1), it was the eucharist. Thus,

When they early church writers spoke of the eucharist, they were explicitly referring to the “tithe” of the early church.

English does not possess the language required to match how the early writers wrote. If we use the loaded English term “tithe” the Roman Catholic will rightly object against the idea that the early writers instituted a proper Old Testament 10% tithe. But if we use the loaded term “eucharist” instead, the Roman Catholic will implicitly not see the tithe offering at all due to his prior assumptions.

When the early writers used the term eucharist, they were referring to the giving of tithes, but if I or and early writer says eucharist, nobody now listening—except for the ultra-rare student of the book of Leviticus—is envisioning a tithe. It is now essentially impossible to fully communicate what is meant using that term alone.

Long gone are the days when each congregant brought their eucharist in a box or basket, to be brought forward at the proper time and then, upon reception, offered to God with a prayer and song of thanksgiving (eucharist). Long gone are the days when the elders would then take portions of the staples (bread and wine) from the eucharist and consecrate them for the Lord’s Supper. Now, someone from the church goes to the supermarket and buys the bread and wine using the funds from the church’s bank account. We have a hard time even comprehending what eucharist meant to the early writers because we stopped practicing it in that form.

Thus, we use the term tithe as the best English term available, and then we supplement it with argument to explain specifically what we mean. In the face of theological disagreement, it is the best option available.

But make no mistake: all of the early writers referred to the eucharist as a “tithe” by the simple act of calling it the eucharist.

The Firstfruits

Early writers[3] offered firstfruits to support the clergy and others in need. Firstfruits is a term that essentially doesn’t exist in English outside of the Bible. Firstfruits closely overlap with the tithes and are often mentioned together without any other distinction. They are given to the priests, just like the tithes.[4] But, unlike the tithe, the firstfruits are not necessarily a tenth. The point of the firstfruits offering was on the quality, not quantity: to give the very best of the harvest to God.

The Hebrews were to give their firstfruits from the beginning of harvest (Deuteronomy 26:1-11)—a token contained in a basket—and then at the completion of the harvest to calculate the yield and reserve 10% in addition to the firstfruits offering.[5]

You can read more examples of this in 2 Chronicles 31:5 and Nehemiah 12:44-47. Notice specifically how the songs of praise and thanksgiving are implicitly linked to bringing the tithes and firstfruit offerings into the storerooms (including the people providing daily portions).

Some early writers who write about the eucharist do also describe the giving of the firstfruits. This reflects the early church practice of quantitatively non-specific tithing. The early church gave the best it had to offer when it “tithed” what it had out of thanksgiving (eucharist) for what God had done for them.

This is why when we read…

You offer defiled food on my altar. But you say, ‘How have we defiled you?’ By saying, ‘Yahweh’s table is contemptible.’ “When you offer the blind for sacrifice, is that not evil? And when you offer the lame and sick, is that not evil? Present it now to your governor! Will he be pleased with you or accept you?” says Yahweh of Armies. “So now plead for God’s favor that he will be gracious to us. With such an offering from your hands, will he accept any of you?” says Yahweh of Armies. “Oh that there were one among you who would shut the doors of the Temple, so that you would not kindle a fire on my altar in vain! I am not pleased with you,” says Yahweh of Armies, “and I will not accept an offering from your hands. “For from the rising of the sun even to its setting, my name will be great among the nations. And in every place there will be incense burned for my name, and offerings made that are pure, because my name will be great among the nations,” says Yahweh of Armies.

…we know that the prophecy of restoration is referring to the cessation of the sacrifices on the alter and their replacement by thanksgiving sacrifices in spirit and truth: pure offerings of thanksgiving, which necessarily, by the Law, included the tithes and firstfruits of the Table of the Lord.[1][6]

“From the days of your fathers you have turned aside from my ordinances and have not kept them. Return to me and I will return to you, says Yahweh of Armies. But you say, ‘How are we to return?’ Will a man rob God? Yet you rob me! But you say, ‘How have we robbed you?’ In tithes and offerings. You are cursed by the curse, for you are robbing me, even this whole nation. Bring the whole tithe into the storehouse, that there may be food in my house; and test me now in this, says Yahweh of Armies, if I will not open the windows of heaven for you and pour you out a blessing that there will not be room enough for. I will rebuke the devourer for your sakes and he will not destroy the fruit of your ground, nor will your vine in the field cast its fruit before its time, says Yahweh of Armies. All nations will call you blessed, for you will be a delightful land, says Yahweh of Armies.

For this same is prophesied by Jeremiah:

“This is what the Lord says: ‘You say about this place, “It is a desolate waste, without people or animals.” Yet in the towns of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem that are deserted, inhabited by neither people nor animals, there will be heard once more the sounds of joy and gladness, the voices of bride and bridegroom, and the voices of those who bring thank offerings to the house of the Lord, saying,

“Give thanks to the Lord Almighty,

for the Lord is good;

his love endures forever.”

For I will restore the fortunes of the land as they were before,’ says the Lord.

With the cessation of the sacrifice, no longer was a victim offered. God no longer desired such sacrifices.[7] We just offer the thank offerings now, bringing out eucharist into the storehouse of the Lord.

On the Cessation of Sacrifices

Justin Martyr, explicitly states that Malachi 1:11 is fulfilled in the Gentiles’ offering of the Eucharist.

‘I have no pleasure in you, saith the Lord; and I will not accept your sacrifices at your hands: for, from the rising of the sun unto the going down of the same, My name has been glorified among the Gentiles, and in every place incense is offered to My name, and a pure offering: for My name is great among the Gentiles, saith the Lord: but ye profane it.’

He then speaks of those Gentiles, namely us, who in every place offer sacrifices to Him, i.e., the bread of the Eucharist, and also the cup of the Eucharist, affirming both that we glorify His name, and that you profane.

— Dialogue with Trypho, XLI

In the previous chapter, however, Justin Martyr explicitly states that after Christ’s suffering and death on the cross, all sacrifices cease:

The mystery, then, of the lamb which God enjoined to be sacrificed as the passover, was a type of Christ; with whose blood, in proportion to their faith in Him, they anoint their houses, i.e., themselves, who believe on Him. For that the creation which God created–to wit, Adam–was a house for the spirit which proceeded from God, you all can understand. And that this injunction was temporary, I prove thus. God does not permit the lamb of the passover to be sacrificed in any other place than where His name was named; knowing that the days will come, after the suffering of Christ, when even the place in Jerusalem shall be given over to your enemies, and all the offerings, in short, shall cease.

— Dialogue with Trypho, XL

Meanwhile back in chapter XLI, Justin Martyr explains just what kind of “offering” the Eucharist was in the early church:

And the offering of fine flour, sirs,” I said, “which was prescribed to be presented on behalf of those purified from leprosy, was a type of the bread of the Eucharist, the celebration of which our Lord Jesus Christ prescribed, in remembrance of the suffering which He endured on behalf of those who are purified in soul from all iniquity, in order that we may at the same time thank God for having created the world, with all things therein, for the sake of man, and for delivering us from the evil in which we were, and for utterly overthrowing principalities and powers by Him who suffered according to His will.

— Dialogue with Trypho, XLI

In other words, after Christ’s death, all sacrifices cease, and the Eucharist is a “thank offering” in which Christians gather to thank God for having already cleansed them. You may take note, for example, that the “fine flour” to which Justin Martyr refers is from Leviticus 14:10 & 21, and the flour is offered not to heal the leper, but because the leper is already healed. This is the sense in which Justin Martyr likens the “fine flour” offering of a cured leper to the Eucharist which is not to represent Christ’s sufferings to the Father, but rather “in remembrance of the suffering which He endured on behalf of those who are [already] purified.”

There was no “sacrifice of the Mass” in the early church. The Roman Catholic sacrifice of the Mass was a later innovation, as was Eucharistic adoration.

The original todah—a freewill thanksgiving peace offering—typically included a lamb. The people were responsible for bringing loaves of unleavened and leavened bread. The first portion of each—a tithe[8]—was given to the priest to supply his needs. But, the priest would also typically provide and sacrifice a lamb. A meal would then take place which combined all the offerings, whether sacrificed on the altar or not.

Within this context, Justin Martyr’s statements make more sense. All blood sacrifices—lamb, goat, bull, etc.—of all types under the Old Covenant ceased with the fall of Jerusalem in 70AD. No longer was the altar needed to make offerings to God. But, the thanksgiving (todah; eucharist) offering would continue without making a sacrifice on the altar. In fact, no altar at all was needed, which is why the early church could meet in homes (or even catacombs) and why many denominations today do not have an altar in their meeting halls.

In Hebrew thought, there were sacrifices (zevaḥim, korbanot) and there were tithes (maʿăśēr). Tithes maʿăśēr are not called zevaḥ (“sacrifice”) or korban (“offering brought near”). This is why Justin Martyr was not contradicting himself when he said the sacrifices ended, but the eucharist offerings were the fulfillment of Malachi’s prophecy. The offering of tithes and gifts continued as sacrificial offerings in the only mode still available. And it included tithes of food for those in need (among other things).

Now, per Justin, the bread and wine are offered, but no offering of flesh is made. That offering of “fine flours” in the early church was a thanksgiving offering to thank God for already being delivered, healed, redeemed, cleansed, cured, and purified. Thus does Justin Martyr assert—in the bolded text of Dialogue XLI (quoted above and also here)…

And the offering of fine flour, sirs,” I said, “which was prescribed to be presented on behalf of those purified from leprosy, was a type of the bread of the Eucharist, the celebration of which our Lord Jesus Christ prescribed, in remembrance of the suffering which He endured on behalf of those who are purified in soul from all iniquity, in order that we may at the same time thank God for having created the world, with all things therein, for the sake of man, and for delivering us from the evil in which we were, and for utterly overthrowing principalities and powers by Him who suffered according to His will.

— Dialogue with Trypho, XLI

—that the eucharist fulfills the requirements of tradition to be classified as the Hebrew todah. You can read more about these traditions in Stephen Pimentel’s piece “The Todah Sacrifice as Pattern for the Eucharist” at Catholic Culture.

As we will see, Justin Martyr was not alone in this view.

Jewish Rabbis

Back during my series on the eucharist, I discussed Roman Catholic apologist FishEaters’ claim about the abolishment of the sacrifice (here, here, and later here).

First she wrote about the Thanksgiving offering:

Interestingly, even the Jewish rabbis said in the Midrash that, when the Messiah comes, all offerings will be abolished except the thanksgiving todah offering (Vayikra Rabba 9,2).

While FishEaters is correct that the sacrifices would end, her Jewish reference (from the 5th century Jewish Midrash on Leviticus 7:11-12) does not support her claim:

This is the law of the peace offering that one sacrifices to the Lord.” That is what the verse says: “One who slaughters a thanks offering honors Me” (Psalms 50:23). It is not written here “One who slaughters a sin offering,” or “one who slaughters a guilt offering,” but rather, “one who slaughters a thanks offering.” Why? A sin offering comes due to a sin and a guilt offering comes due to a sin. A thanks offering does not come due to a sin, “if he sacrifices it as a thanks offering.”

…

Rabbi Pinḥas, Rabbi Levi, and Rabbi Yoḥanan in the name of Rabbi Menaḥem of Galya: In the future, all the offerings will be abolished but the thanks offering will not be abolished. All the prayers will be abolished, but the thanksgiving [prayer] will not be abolished. That is what is written:

this is the thanksgiving [prayer];

this is the thanks offering. Likewise, David says:

Toda is not written here, but todot, thanksgiving and a thanks offering.

Citation: “Vayikra Rabbah 9.” The Sefria Midrash Rabbah (2022)

Did the Messiah come to abolish all offerings and all prayers except the thanksgiving? When has the Roman Catholic church abolished all prayers except the thanksgiving? Perhaps it has abolished prayers to the dead and prayers to the saints?

Then she wrote about the Paschal offering:

Now, this Passover offering is intimately associated with (rabbis even call the yearly memorial a form of) Korban Todah insofar as a Korban Todah is obligatory when one has been saved from danger, as what happened when God spared the Hebrews’ firstborn. These two korbanot go hand in hand.

Note: most fascinating, and relevant to the common Protestant accusations of Catholics “re-crucifiying” Jesus and denying the efficacy of His once and for all sacrifice at Golgotha, is the Seder practice of quoting from the Haggada, ” v’hi sh’amda l’avoteinu… sheb’chol dor v’dor omdim aleinu l’chaloteinu…,” that is: the Israelites’ national redemption was not only a “one-time historical event” but perpetual in every generation.

See here

If Jesus abolished all sacrifice except the thanksgiving, then the purpose of the Lord’s Supper is to thank God for the already completed sacrifice of his son and the salvation that he brought, which is precisely what a remembrance service accomplishes. After all, when Jesus went to the cross for us, he caused death to permanently pass over us. So every time we gather, in perpetuity, we are to give thanks for that. That thanks is our thanksgiving, our only thanksgiving. But the Roman Catholic does not believe this. He believes in a propitiatory sacrifice. The ancient todah was not propitiatory.

A thanks offering does not come due to a sin…

Now, let’s consider Roman Catholic Marty Barrack, who also agrees that the ancient writers believed that the todah—thanksgiving—sacrifice would not end:

The sages believed that the todah sacrifice would continue for all eternity because we would always need to thank God for everything.

The ancient rabbis believed that when the Messiah would come all sacrifices except the Todah would cease, but the Todah would continue for all eternity. In 70 AD the Temple fell to earth and all of the bloody animal sacrifices stopped. Only the Todah remains, the eucharistia, the Final Sacrifice at which the last words spoken are Todah l’Adonai, “Thanks be to God.”

I have cited these three sources for four reasons.

First, the Roman Catholic is citing sources that does not support her position, but the sources do confirm what Justin Martyr taught about the thanksgiving (eucharist) replacing the sacrifice.

Second, the Paschal sacrifice was abolished at the moment of Christ’s death and resurrection: the sacrifice of the eucharist is not—and cannot be—of itself a Passover sacrifice.[9]

Third, even the Jews agreed that the Messiah abolishes the Paschal sacrifice!

Fourth, the Jews understood that the thanksgiving sacrifice was not propitiatory.

The purpose of the eucharist and the purpose of the tithe are identical: to thank God. That’s because they are the same offering.

Why is the Tithe Called Thanksgiving?

In the Pentateuch, Melchizedek, the Levites, the priests, the poor, the widows, and the orphans all received their provisions from various tithes. After reading the Pentateuch itself, I suggest you continue your research with this overview, which cites an abridged set of chapters and verses as well as links for more information.

The early church did all of these things, supporting the apostles, elders, and deacons, as well as those who were poor or needy. Just as priests received the grains, wine, oil, fruit, and cattle (Numbers 18:21-26; Leviticus 27:30–33), so were all of these things (and more) included by the early church in their tithes.

From ancient times, the thanksgiving has always been a combination of the corporeal and incorporeal. Even in Leviticus the thanksgiving included both corporeal food and incorporeal thanks, both of which are offered as holy sacrifices to God.

Todah literally means “thanksgiving.” In addition to the sense of thanksgiving or gratitude, it also has a strong connotation of praise. The todah offering was accompanied by an associated type of song, usually a psalm.

The todah sacrifice was offered by a person whose life had been redeemed or delivered from a great danger.

The person who had been delivered would express his gratitude to God by celebrating a sacrificial meal with family and friends. A priest would normally sacrifice a lamb and consecrate bread in the temple. The meat and bread would then be brought home for the meal, along with wine.

The meal would then be accompanied by songs of thanksgiving. Todah songs have a characteristic movement from lament to praise. Sometimes, the song is actually structured with two halves, the first a lament, the second a praise. The lament recounts the circumstance of impending death and the prayer to God for deliverance. The praise recalls and proclaims the deliverance from death, for which God is thanked and praised.

We can find many such examples in the Psalms. But we can also see it elsewhere. Nehemiah 11:17 ties together the priestly thanksgiving and prayer, Nehemiah 12:8 references priestly thanksgiving with song, and Nehemiah 12:27 ties together priestly thanksgiving with praise. Amos 4:5 describes the freewill thanksgiving offering. Jonah 2:9 describes sacrificing shouts of thanksgiving praise.

So why is the tithe offering called the eucharist? It is straightforward.

That the tithe was (and still is) an offering is well-established and uncontested. Similarly, the only offering made by the church was (and still is) the eucharist. This too is well-established and uncontested. Thus, it is the only logical possibility that the tithe is the eucharist. In particular, the eucharist is the thanksgiving offering of all of both corporeal and incorporeal elements.

This is why Justin Martyr’s analysis is so important. He claims that all sacrifices have ceased, except for the sacrifice of Malachi’s prophecy which continues in the eucharist (which is the todah). All we need to know is if the church offered a sacrifice of praise and tithes as its eucharist. And it did! I encourage you to read the conclusion of the series on the eucharist, where we summarize the eleven early writers who associated the prophesy of Malachi with the thanksgiving alongside other early writers who referenced many of the other related Old Testament passages.

Malachi and the Showbread

In the Old Testament, the showbread was of course offered to God (by being placed on the table). That is what made it holy. It was also a sacrifice in the sense that the ingredients (and time to make the bread) were given in the service of God. But, it was not sacrificed on the altar, that is, burned. Indeed, it had nothing to do with the altar. Rather, the bread was consumed by the priests once it was a week old (and replaced by new bread).

Malachi 1:7,12-13 speaks of the Lord’s Table. Which table is this? Naturally, this includes the ‘Table of the Bread of the Presence’, from which the priest were permitted to eat week-old showbread. More than this, it also included profaning the altar (the showbread was not sacrificed!) upon which the priests received a portion of food (from the tithe!). The priests in Malachi showed contempt for all of this:

Malachi uses a play-on-words, referring to both the literal table they eat from (showbread; table of the bread of the presence) and the figurative table from which the Lord provides them (portion of the sacrifices; the altar).

Sandwiched between this are verses 10 and 11:

God utterly rejected the sacrifices of these priests. Instead, it would one day be that all nations would offer sacrifices in all places without the need for these priests to officiate. Jesus revealed the fulfillment to Malachi’s prophecy as he spoke to the Samaritan woman.

Thus, I always ask again and again:

To what sacrifice was Jesus referring when he said that the time has now come to worship the Father in Spirit and truth?

It couldn’t have been the paschal sacrifice of Christ, for that had not yet taken place. No, it was the todah sacrifice of thanksgiving, the one the church adopted.

It is also worth asking, where did the flour and oil come from to make the showbread? Of course it must have come from (directly or indirectly) the offerings, including the tithes.

The New Testament

By now we’ve established that the eucharist is an offering of the physical and the non-physical to God. It includes non-corporeal things like thanks, praise, song, and service alongside corporeal things like bread, wine, cheese, and oil. We offer our thanks to God in many different ways, but all are the eucharist and all are thanksgiving.

Now, what does the New Testament have to say?

Here Paul describes the eucharist in terms of the voluntary giving of tithes, prayers, good works, and service for the poor and needy:

Consider this: whoever sows sparingly will also reap sparingly, and whoever sows bountifully will also reap bountifully. Let each one give as he has previously decided in his heart, not grudgingly, or of necessity, for God loves a cheerful giver. And God is able to make all grace come in abundance to you, so that always having all sufficiency in everything, you can have an abundance for every good work. As it is written, He has scattered abroad, he has given to the poor, his righteousness endures forever. And he who is supplying seed to the sower and bread for food, will supply and multiply your seed for sowing, and increase the harvest of your righteousness. You will be enriched in every way so that you can be generous on every occasion, which through us is producing thanksgiving to God. For the service of this ministry is not only supplying the needs of the holy ones, but overflows by means of many thanksgivings to God. Because of the proof given by this service, they will glorify God for your obedience to your confession of the good news of Christ, and for the generosity of your contribution to them and to all, while they themselves also, with prayers on your behalf, yearn for you because of the surpassing grace of God on you. Thanks be to God for his indescribable gift!

Here Paul again Paul refers to voluntarily gathering of the tithe to support those who serve the church:

Now concerning the collection for the holy ones, as I gave orders to the churches of Galatia, so you also are to do. On the first day of every week each one of you is to set something aside, storing up whatever he has prospered in, so that no collections are made when I come. And when I arrive, whomever you approve to carry your gracious gift to Jerusalem, I will send them with letters of introduction, and if it is right for me to go also, they will go with me.

Here good works are sacrificed:

I beseech you therefore, brethren, by the mercies of God, that ye present your bodies a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable unto God, which is your reasonable service.

And here praises are sacrificed:

By him therefore let us offer the sacrifice of praise to God continually, that is, the fruit of our lips giving thanks to his name.

Here Jesus demonstrates the free will offering of gifts:

And he looked up and saw the rich people who were putting their gifts into the offering box. And he saw a certain poor widow putting two leptonsa into it. And he said, “Truly I say to you, this poor widow put in more than any of them, because all of these people put in gifts out of their abundance, but she, out of her poverty, put in all that she had to live on.

We pause here to note briefly that when the Roman Catholic quotes Clement of Rome (from the 1st century AD)…

— Clement of Rome, “Letter to the Corinthians.”44:4–5. 80AD.”

Citation: “The Sacrifice of the Mass.” Catholic Answers.

…it does so by treating the word “gift” found in Luke 21 as the “sacrifices” offered in the eucharist. Here is the original language:

Timothy F. Kauffman explains:

The word, δῶρα, is the same word used in the Gospel of Luke to refer to the tithes being deposited into the temple treasury (Luke 21:1). In the same letter, Clement also instructed the rich to “provide for the wants of the poor” and the poor to “bless God” for the rich “by whom his need may be supplied” for “we ought for everything to give Him thanks (ευχαριστειν)” (Clement, to the Corinthians 38; Migne P.G., vol I, 285).

The truth is, in paragraph 44 of his letter, Clement had described the presbyters’ faithful and honorable handling of the tithes, not their alleged offering of consecrated bread and wine. Translators of all stripes have suppressed that simple truth, avoiding in the English translations the word δῶρα (dora) in the Greek, a plain reference to the tithe offerings.

The todah gifts—offered with thanksgiving—are the eucharist.

What about Jesus giving thanks before meals? He did so before the Feeding of the 5,000 (Matthew 14:19-21; Mark 6:41; Luke 9:16; John 6:11), before the Feeding of the 4,000 (Matthew 15:34-37; Mark 8:6-7), before the Last Supper (Matthew 26:26-29; Mark 14:22-23; Luke 22:17-19; 1 Corinthians 11:24), and after his resurrection (Luke 24:30-31). Paul’s example is recorded in Acts 27:35.

All of the above examples are the eucharist. All of these are Malachi’s todah sacrifice.

But what about the Paschal sacrifice? Doesn’t the New Testament combine the Paschal and Todah sacrifices together into one? That’s the claim many Roman Catholics make. For example:

Not according to St. Paul in scripture.

The reality is that there are only five references to eucharist in the New Testament that are contained within a Paschal context. All five of them—Matthew 26:26-29; Mark 14:22-23; Luke 22:17-19; 1 Corinthians 11:24—are a single shared reference to the Last Supper where Jesus gave thanks before the meal, prior to speaking the “words of institution” (or consecration). But, as shown above, there was nothing special about Jesus giving thanks before eating with his disciples. We have good reason to conclude that Jesus eucharisted all of the food he shared in his meals with others, thanking the Lord for the food that they were about to eat and share together.

Paul never directly equates the two sacrifices.

The belief that Paul taught a “Paschal Eucharist” is an hallucination. The text nowhere says any such thing. One must engage in “reverse inference” (i.e. begging the question) from what one already believes in order to come to this conclusion.

On a number of occasions, I’ve asked Roman Catholics how did the thanksgiving (eucharist) sacrifice come to be associated with the Lord’s Supper, since the thanksgiving offering is not related to the Paschal sacrifice (nor the Passover meal)? I’ve received no explanation.

See also: Eucharist Word Usage

Footnotes

[1] The phrase “tithes and offerings” is an ancient phrase to refer to all the gifts that were donated to God and placed in his storehouse:

Will a man rob God? Yet you rob me! But you say, ‘How have we robbed you?’ In tithes and offerings. You are cursed by the curse, for you are robbing me, even this whole nation. Bring the whole tithe into the storehouse, that there may be food in my house; and test me now in this, says Yahweh of Armies, if I will not open the windows of heaven for you and pour you out a blessing that there will not be room enough for.

Notice that the tithes (maʿăśēr) and offerings (terumah) are collectively referred to as the whole tithe (Ekphoría/ἐκφόρια in the Greek LXX), even though it includes portions that are not strictly 10%. The terumah offerings include portions taken from a variety of different offerings, including the firstfruits and the freewill peace offerings. One of these portions comes from the thanksgiving/todah/eucharist. By the Law, every thanksgiving offering included a tithe for those in need:

“This is the law of the sacrifice of peace offerings that a person offers to Yahweh. If he offers it as a thanksgiving, then with the sacrifice of thanksgiving he is to offer unleavened cakes mixed with oil, and unleavened wafers smeared with oil, and cakes of fine flour mixed with oil. Along with the sacrifice of his peace offerings for thanksgiving, he is to offer his approach-offering with cakes of leavened bread. And from it he must offer one of each kind of approach-offering as a contribution to Yahweh. It will belong to the priest who throws the blood of the peace offerings.

[3] For example:

- “The Didache.” Chapter 13

- Irenaeus, “Against Heresies.” Book IV, Chapter 17, ¶5

- Irenaeus, “Against Heresies.” Book IV, Chapter 18, ¶1-2

- Origen, “Against Celcus.” Book VIII, Chapter 34

- Hippolytus, “The Apostolic Tradition (Anaphora).”

[4] See: Numbers 18:12-13 on firstfruits and Numbers 18:21-28 on tithes.

[5] Deuteronomy 26:12; Numbers 18:21-24; Leviticus 27:30-33

[6] The evidence is summarized in “The Eucharist, Part 40: Conclusion.”

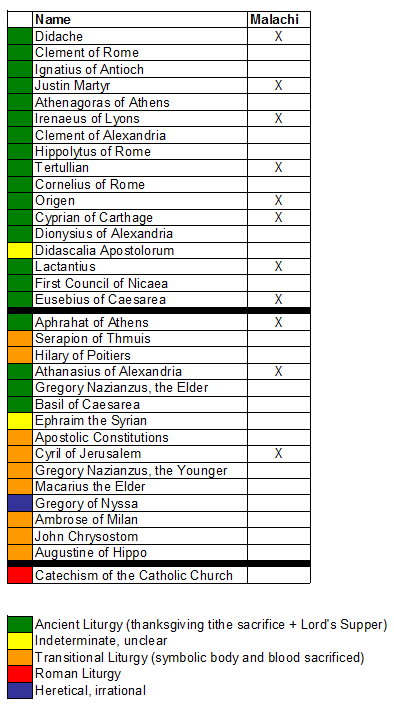

Many times throughout this series—The Didache, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus in Part 6 and Part 36, Tertullian, Origen, Cyprian, Aphrahat, Athanasius, Eusebius, Lactantius, Cyril—we noted that the ancient church viewed the thanksgiving—eucharist—as the sacrificial fulfillment of Malachi 1:11. Over nearly 400 years, eleven out of the thirty-two writers we examined (a full third!) explicitly confirmed this view.

Out of the whole Bible that could have been referenced to discuss the Eucharist, a third chose to discuss Malachi’s prophecy directly, and they uniformly did so to support the ancient, non-Roman conclusion. This is a remarkable testimony. Meanwhile, in that same period, we didn’t see any writer offering Christ’s body up as a fulfillment of Malachi.

[7] This was clearly prophesied on many occasions:

- 1 Samuel 15:22

- Psalm 40:6-8, 51:16-17

- Proverbs 15:8, 21:3

- Isaiah 1:11-17

- Jeremiah 7:22-24

- Hosea 6:6

- Amos 5:21-24

- Micah 6:6-8

[8] This was a tithe in the sense that we mean it today: a freely given gift that is not literally 10%. But like the ancient tithes and firstfruits offerings, this too was taken out of the “firsts” and what was left over remained with the giver. This ensured that the priest was fed.

[9] Roman Catholics commonly conflate the paschal and thanksgiving sacrifices, but this begs-the-question. In the Torah, the paschal sacrifice (pesach) and the thanksgiving sacrifice (todah) are separate. The following is an example of a theological, typological, or analogical claim which is not deduced from the Torah itself:

The todah sacrifice recalled a mortal threat to the people Israel and offered thanks to God for saving them. The first todah feast was the original Passover meal, a thanksgiving for release from slavery in Egypt. Our Father connected the Passover and todah sacrifices with the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist. The Shulkhan Arukh affirms that the matzah at the Passover Seder represents the todah sacrifice. A deep sense of thanks pervades the entire Seder, summarized in the song dayenu.

To support his claim, Barrack cited the Shulkhan Arukh written in 1563. It is based on an earlier work from around c.1300.

* Then the church was wrong for 1000+ years

* None of the early writers identified the eucharist as a tithe

Today we will discuss this latter objection. We’ll save the other for another day.”

i want today, to discuss why none of the objectors (as i suppose most of them are Catolic who our friend Lexetlaw/blog said makes up the majority of redpillers in this statement, ” Christian RP (Catholics > Protestants in number, due to appeals to tradition)” from this post https://sigmaframe.wordpress.com/2021/03/26/charting-the-red-pill-world/ , ever object to the manosphere claim of ”the church became cucked after the idea of chivalry became part of the Western traditions? ”Which i have successfully estimated to be around the year 1100 A.D.

Chivalry was originally about how MEN treated other MEN, but it got perverted fast, and MEN started treating other MEN as objects and women as prizes(i won’t say goddess-even though it’s TRUE) for abusing their fellow MEN.

As Dalrock wrote in ”Confusing history with literature.” from November 20, 2019:

”One of Vox Day’s readers argued:

As Dalrock has explained, all that cultural bomb-throwers have to do is to borrow from the Satanic inversion that is chivalry, that puts women in the place of Jesus.

Vox objected, responding:

That’s not what chivalry is. Dalrock is confusing the literary tradition with the actual military ethos. This is basic Wikipedia-level knowledge.

[Vox quotes Léon Gautier’s Ten Commandments of Chivalry]

There is nothing inversive about it. Ironically, Dalrock’s description of chivalry is the inversion of the concept.

The problem with Vox’s dismissal is that it isn’t me that is confusing literary tradition with history, it is the culture at large, and (as I will show in this post), Vox himself. It was this very confusion that Infogalactic tells us Gautier sought to stamp out when he wrote his ten commandments in 1883:

Léon Gautier, in his La Chevalerie, published for the first time in 1883, bemoaned the “invasion of Breton romans” which replaced the pure military ethos of the crusades with Arthurian fiction and courtly adventures. Gautier tries to give a “popular summary” of what he proposes was the “ancient code of chivalry” of the 11th and 12th centuries derived from the military ethos of the crusades which would evolve into the late medieval notion of chivalry. Gautier’s Ten Commandments of chivalry are…

The problem, as Infogalactic points out (and as I pointed out here), is the very strong tendency for modern readers to mistake fictional Arthurian tales for historical accounts. Yet we can’t blame this entirely on modern readers. This confusion was built in to the Arthurian literature itself. As CS Lewis explained in Allegory of Love (regarding Chrétien de Troyes and his Lancelot, the Knight of the Cart from circa 1177):

Chrétien de Troyes is its greatest representative. His Lancelot is the flower of the courtly tradition in France, as it was in its early maturity…

He was among the first to welcome the Arthurian stories; and to him, as much as to any single writer, we owe the colouring with which the ‘matter of Britain’ has come down to us. He was among the first (in northern France) to choose love as the central theme of a serious poem…

…combining this element with the Arthurian legend, he stamped upon men’s minds indelibly the conception of Arthur’s court as the home par excellence of true and noble love. What was theory for his own age had been practice for the knights of Britain. For it is interesting to notice that he places his ideal in the past. For him already ‘the age of chivalry is dead’.40 It always was: let no one think the worse of it on that account.

This confusion of Arthurian tales of what was much later termed courtly love with actual history is endemic, and has been from all but the very beginning. Wikipedia’s article on the term chivalry likewise explains:

Fans of chivalry have assumed since the late medieval period that there was a time in the past when chivalry was a living institution, when men acted chivalrically, when chivalry was alive and not dead, the imitation of which period would much improve the present. This is the mad mission of Don Quixote, protagonist of the most chivalric novel of all time and inspirer of the chivalry of Sir Walter Scott and of the U.S. South:[19]:205–223 to restore the age of chivalry, and thereby improve his country.[19]:148 It is a version of the myth of the Golden Age.

With the birth of modern historical and literary research, scholars have found that however far back in time “The Age of Chivalry” is searched for, it is always further in the past, even back to the Roman Empire…

Sismondi alludes to the fictitious Arthurian romances about the imaginary Court of King Arthur, which were usually taken as factual presentations of a historical age of chivalry. He continues:

The more closely we look into history, the more clearly shall we perceive that the system of chivalry is an invention almost entirely poetical. It is impossible to distinguish the countries in which it is said to have prevailed. It is always represented as distant from us both in time and place, and whilst the contemporary historians give us a clear, detailed, and complete account of the vices of the court and the great, of the ferocity or corruption of the nobles, and of the servility of the people, we are astonished to find the poets, after a long lapse of time, adorning the very same ages with the most splendid fictions of grace, virtue, and loyalty…

And as I noted above, Vox himself encourages the false belief that Arthurian tales are descriptions of what chivalry was like in the middle ages. In his post 800 percent and rising, Vox was very proud to announce that he was adding back teaching on romantic chivalry to Castalia House’ 2020 edition of Junior Classics, as this would teach modern children about Christian history and values:

To explain why it is important, consider the following preface from Volume 4 of the 1918 edition, “Heroes and Heroines of Chivalry”, which was excised from the 1958 edition for reasons that will be obvious to anyone who is conversant with the concept of social justice convergence and the long-running cultural war against Christianity and the West. And it probably will not surprise you to know that all three of the stories referenced in this preface were also removed from the 1958 edition.

The preface and all four stories will, of course, appear in the 2020 edition.

The preface (and tales) Vox is so proud to have returned to the Junior Classics does exactly what Vox is accusing me of doing. It confuses pure fiction with historical fact. Even worse, it encourages young children to adopt this very confusion:

The word chivalry is taken from the French cheval, a horse. A knight was a young man, the son of a good family, who was allowed to wear arms. In the story “How the Child of the Sea was made Knight,” we are told how a boy of twelve became a page to the queen, and in the opening pages of the story “The Adventures of Sir Gareth,” we get a glimpse of a young man growing up at the court of King Arthur. It was not an easy life, that of a boy who wished to become a knight, but it made a man of him…

The preface goes on to explain that an essential part of making a man of a boy was to teach him to follow the ethic of courtly love:

His service to the ladies had now reached the point where he picked out a lady to serve loyally. His endeavor was to please her in all things, in order that he might be known as her knight, and wear her glove or scarf as a badge or favor when he entered the lists of a joust or tournament.

Finally the preface explains that the Arthurian version of chivialry, which combines both martial virtues and servility to women, is historical and is what the word chivalry means:

The same qualities that made a manful fighter then, make one now: to speak the truth, to perform a promise to the utmost, to reverence all women, to be constant in love, to despise luxury, to be simple and modest and gentle in heart, to help the weak and take no unfair advantage of an inferior. This was the ideal of the age, and chivalry is the word that expresses that ideal.

What is going on here is a classic game of Motte and Bailey. When Vox wants to sell courtly love as Christian, he points to Arthurian tales that teach chivalry, what it used to be like to become a man. This is nonsense, not only because Arthurian tales aren’t history (not even close), but also because the values of Arthurian tales aren’t remotely Christian. They are, in fact, a parody of Christianity, and were from the beginning. Courtly love was a devious joke decadent medieval nobles used to mock Christianity. As the 1918 preface to Junior Classics demonstrates, long ago Christians forgot that this was a mockery of Christianity and accepted it as not only Christian but history. The courtly love version of chivalry is the bailey that Vox is selling not just to his readers, but to their unsuspecting children. Yet when my assertion of the evil of courtly love is mentioned by one of his readers, Vox retreats to the motte, claiming that everyone knows the Arthurian/fictional/courtly love version of chivalry isn’t really chivalry at all! In the process, Vox accuses me of falling for the same misdirection that he is so proud to include his his revival of Junior Classics.

Vox needs to choose either the motte or the bailey when it comes to chivalry. Either we need to teach modern children Arthurian tales of courtly love in order to restore Christian culture and values, or we need to annihilate this abomination and replace it with the Ten Commandments of Chivalry Léon Gautier wrote in 1883 in a failed attempt to reframe chivalry to Christian values (away from the dominant fictional/Arthurian view of the term). If he wishes to do the latter, he will quite literally need to stop the presses.”

See how ST.DAL didn’t care if he may have caused a rift in the manosphere to tell what is TRUE?Just like i and Derek!i guess we’re saints too then! Perhaps even ”rabble rouser”( as one commenter said of him about a year or so ago at sf)MOD also is a saint!-Here’s a fun fact:All washed in the blood CHRIST ians are saints(proof?:”22 All the saints (God’s consecrated ones here) wish to be remembered to you, especially those of Caesar’s household.-Philippians 4:22

Amplified Bible, Classic Edition (AMPC) ”, only the big shots in the church like to claim it can make some ”saints” is all.

Chivalry was a “code” or set of standards throughout Medieval Europe. Yes, there was one part of that on the way to “treat women” as a “brave Knight” of your respected Kingdom.

It did not apply to peasants / serfs (which was alomost 100% of the population Medieval Europe)

I do have some decent and armchair knowledge of “Arthianian Legand” of pre and post Roman / pre Norman Britain.

What we do know is that the whole Chivalric Codes and the like did not exist in the time of Arthur (if he actually existed). That was all Victorian additions (‘Idylls of the King ‘ byTennyson) and Hollywood after that in the modern era (musicals like Camelot, movies like Excalibur, Disneyfied productions of animated show / movies and other fictional literature, programs)

The whole mythos has built another layer on top of what was already scant information. Muddled together with late middle ages mythos, combined with other trappings that never existed in Medieval England or Wales.

Merlin, the wizard was probably a Druid, and was probably Welsh, if he ever existed. (the shamans and holy-ones of the faith of the Welsh and Irish……the pre-christendom faith of many swaths of Celtic Britain, before the Romans ever arrived).

What we do know from written Welsh records AFTER the Romans departed Britain is that there was a legend of a “king” (probably a Chieftan) who became “Arthur” and became woven INTO the fabric of what became England.

There were no titles of Sir and “knight” and the like until well after the Normans conqured England in 1066. Arthur, and the whole gang (Merlin, Gwain, Lancelot, Arthur, Morgan Le Fay….all of them, IF they ever existed were add ons after the fact). There was not even a Heraldric culture in Britain until after 1066.

So when did Arthur live? Probably in a time between before the Noman conquest in 1066 and probably just afte the Romans departed.

This “legend” has taken a world of its own, and we today want to believe in a better and pure time of a King “that united” the fiefdoms, principalities, lesser Kingdoms into a “united” kingdom of Britons. Along with swords, courtly love, honor, dragons, evil knights (is there such a thing???), magic, potions, spells, wizards , beautiful maidens that needed rescue, treasure and castles.