Over at Anabaptist Faith, commenter Seeker gives the standard objection:

Would the author be so kind as to list the number and types of Anabaptist communities that are not in communion with each other due to endless doctrinal disputes? I’m afraid not.

Are Anabaptist’s any less skilled in this practice?

We’ve heard this before:

But regarding the question “what is truth?” this objection is a non-sequitur. All that the varied disagreement of denominations proves is that people will always try to disagree with each other, for whatever reason. This has no bearing on what is actually true.

The spiritual pride and generational arrogance needed to make this type of claim is almost enough to make one weep if it were not so patently absurd.

And now we get to the heart of the matter:

First comes the non-sequitur. Next, judgment swiftly follows. In doing so, Seeker has self-refuted his own claim.

In light of this, now we will see how Seeker’s objection falls to pieces:

except…

Seeker will now list four doctrines of the Christian faith that are excluded from Anabaptism, but he is sure are central doctrines of the early church. Guess what the first one is?

a. The centrality of the Eucharist as taught by all of the ancient faiths and the unanimous consent of the church fathers to the sacramental nature of this act of worship. What could possibly be more central than the words

of Christ in John 6:

Or when he said,

“Take eat this is my body”

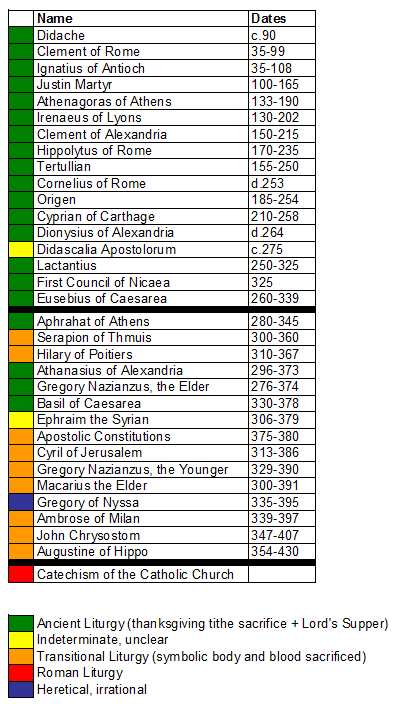

Thus, Seeker betrays his own historical ignorance and refutes his own argument. We did a 40-part series on “The Eucharist and the Early Church” in which we found this:

Yes, that’s right. In the first three centuries of the church, the sacrifice of the blood and body of Christ by the church was not taught by any early church fathers. Far from being unanimous, the Roman Catholic liturgy was completely absent. It wasn’t until the late fourth century when Roman Catholicism arose that this changed. The transition in the language and practice of the Eucharist during that period is quite noticeable!

But who does Seeker cite as evidence of the early church attestation? Yup, “Saint” Ignatius of Antioch!

Saint Ignatius of Antioch emphasized this as he traveled to his death by stating that all those who deny the real presence of Christ are heretics and should be shunned. Now the author may or may not hold to the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. If he does, he will not voice this opinion out loud in any reputable conservative Anabaptist church least he risk being branded as having fallen into the “false teaching” of that Romish “whore”.

Here’s a little summary of “The Eucharist, Part 4: Ignatius of Antioch.” Ignatius calls the bread of the Lord’s Supper “the Bread of God” not the “Bread of Christ.” He calls the blood “love incorruptible,” an obviously metaphorical use. But the crux is found in the Epistle to the Smyrnaeans. There Ignatius notes that the Gnostics could not consecrate the unconsecrated thanksgiving offering (eucharist) that was already offered to God, because they would have had to say “this is my body, this is my blood.” They denied the physical death and resurrection of Christ.

So let’s spell this out slowly.

The thanksgiving offering of tithes and prayers were offered to God. Then, some of the bread and wine were taken out of the eucharist, consecrated by speaking the words of institution, and then consumed during the Lord’s Supper. This is the ancient liturgy that is in direct contradiction to the Roman liturgy. The Gnostics abstained from the thanksgiving offering of unconsecrated food and drink. How do we know this? Because the tithe was used to support the poor and they refused to help the poor. Because they did not tithe, they did not consecrate the tithe. Because they did not consecrate the tithe, they did not participate in the Lord’s Supper.

Ignatius never promoted the “Real Presence” of Christ in the bread and wine, because no writer in that period did. It was a much later innovation. For more information, see Timothy F. Kauffman’s “Eating Ignatius.”

Oh, and the Eucharist is not a sacrament. That’s an anachronism too. It, more-or-less, arose in the fourth century. See the discussion in “Changing Language.”

b. The covenantal nature of Faith and the teaching and practice from early records of the glad welcoming into the Church, by baptism, of the youngest members of the human race. Rather, you believe in innocence in infancy, a poorly defined addition of “age of accountability”, and an experiential salvation based on the person’s ability to make a reasoned profession of faith. You will have no answer to the question of salvation for the person who dies around the “age of accountability” or the mentally handicapped person who is unable to make a reasoned profession of faith.

I learned of Covenantal faith as an Anabaptist. But there is no indication that the early church baptized infants. I don’t have time to fully defend this claim right now, but considering the other claims don’t hold up to scrutiny, I don’t see how it is worth the time to pursue this one further. If anyone is interested in a more detailed exploration of this topic, let me know.

c. Of Baptism, you will deny the salvific effects of baptism. Rather, you will hold to a symbolic view, where baptism is an outward sign of a “supposed” inner reality.

The early church did not teach baptismal regeneration. As with the Roman Catholic Eucharist, that is a doctrinal innovation of the late fourth century and subsequent centuries.

d. You will deny the authority of the Church and it’s prerogative to proclaim doctrine. You will hold, more or less, to the Protestant teaching of “sola Scriptura”. As stated by this author “just take Jesus and the apostles at their word” This provides blatant cover for the very real reality in Anabaptist churches of every man becoming his own pope. If you don’t like what your elders are teaching, proclaim your greater spiritual insight, attract half of your church to your views and just go start your own splinter group. This belief and practice completely disregards the fact that the church is” the pillar and ground of the truth” according to scripture.

The whole…

…is not the scathing criticism that Seeker seems to think it is. Supposedly we should reject Anabaptists because of “endless doctrinal disputes” but to prove his point, he argues that there is a doctrine that we all agree on? Alright. You win. Guilty as charged. We all universally agree and our doctrine is not in dispute. I guess you’ll join us now?

Anyway, the church is not an it. It is a plural group of persons. Protestants and Anabaptists definitely affirm the authority of the church—the persons who profess faith in Christ. It’s interesting how he has redefined church and then used his redefinition to determine that the church… his definition of the church.. is “the pillar and ground of truth.” We can see that sleight of hand!

But we’ve arrived back where we started, with the non sequitur. If two groups split, it doesn’t imply that none of them are correct. Seeker seems to want you to conclude that disagreement means that no one can be right, but that’s simply not a logical conclusion. It doesn’t address the question of what the actual truth is. And, notably, the Roman Catholic Church also does not address the question of what the actual truth is, so Seeker is offering nothing of value anyway. His appeal to authority is just an empty non sequitur (and a logical fallacy).

Seeker follows this up with another comment where he attempts to defend infant baptism:

What if we understood, as did the fathers, that baptism was sacramental? Not something that man does but the Church does as a means of administering divine grace.

To someone who isn’t a Roman Catholic, this comment doesn’t make sense. If you’ve only read your Bible, you’d have no idea what he is talking about. That’s because none of what he is describing is biblical. It’s not even historical back to the early church.

I first wrote about the conflation of sacrament and mystery in “Sacraments are the Reason for the Priesthood” where we noted that a sacred secret (Greek: mustērion) is a different word than a sacred vow (Latin: sacramentum). The whole Roman Catholic system of priests “administering sacraments and graces” is derived from a conflation of words in the late 4th century in the Latin Vulgate.

Then in “What is Grace?,” I wrote about how marriage between a husband and wife was conflated with the mystery of the marriage between Christ and his Church and a system of meritorious and salvific grace was manufactured from out of this conflation.

In “Soteriology” I shared this article by Roman Catholic Joshua Charles on, of all things, “Baptismal Regeneration.” There he explicitly contrasts sola fide (faith alone) with baptismal regeneration and the “sacrament” of baptism. Without baptism being a sacrament, there can be no baptismal regeneration. They, along with the Roman Catholic concept of grace, rise and fall together.

In my series on the Eucharist, I wrote about the development of the concept of sacraments. You can read about that in:

Part 9 on Tertullian (155-250)

Part 28 on Basil of Caesarea (330-378)

Part 30 on John Chrysostom (347-407)

Part 31 on Ambrose of Milan (339-397)

Part 34 on Hilary of Poitiers (310-367)

Part 40

The writers of the late 4th century (and later) took Tertullian’s second- and third-century Latin writings and twisted it into a new doctrine.

Finally, I explained how the development of the language of sacraments and mysteries came to pass over centuries of “Changing Language.”

So let’s be clear: the Roman Catholic conception of sacraments is an anachronistic fabrication.

In part 2, we’ll revisit Tertullian and discuss precisely how Tertullian’s words were twisted to create the sacramental system. In part 3, we’ll expound more on how baptismal regeneration was developed in conjunction with the system of sacraments.

Pingback: Sacraments, Part 3: Baptismal Regeneration - Derek L. Ramsey

Pingback: The Eucharist, Redux #6: AI Apologist - Derek L. Ramsey