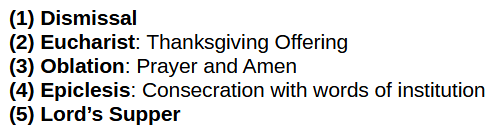

The original liturgy:

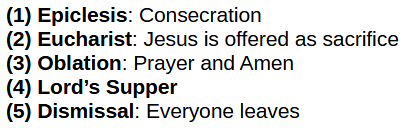

The Roman liturgy:

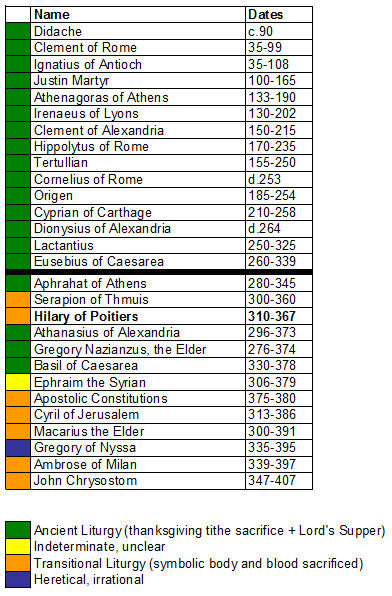

Hilary of Poitiers (310-367)

Let’s start immediately with the quotation that FishEaters provides:

As to the reality of His Flesh and Blood, there is no room left for doubt, because now, both by the declaration of the Lord Himself and by our own faith, it is truly Flesh and it is truly Blood. And These Elements bring it about, when taken and consumed, that we are in Christ and Christ is in us. Is this not true? Let those who deny that Jesus Christ is true God be free to find these things untrue. But He Himself is in us through the flesh and we are in Him, while that which we are with Him is in God.

Citation: Hilary of Poitiers, “On the Trinity, Book 8.” Paragraph 14 (c.360)

Hilary is writing about the Trinity and how the elements of the Last Supper pertain to it. It is a bit vague from this clipped paragraph precisely what is being discussed. Let’s back it up a paragraph:

Now I ask those who bring forward a unity of will between Father and Son, whether Christ is in us today through verity of nature or through agreement of will. For if in truth the Word has been made flesh and we in very truth receive the Word made flesh as food from the Lord, are we not bound to believe that He abides in us naturally, Who, born as a man, has assumed the nature of our flesh now inseparable from Himself, and has conjoined the nature of His own flesh to the nature of the eternal Godhead in the sacrament by which His flesh is communicated to us? For so are we all one, because the Father is in Christ and Christ in us. Whosoever then shall deny that the Father is in Christ naturally must first deny that either he is himself in Christ naturally, or Christ in him, because the Father in Christ and Christ in us make us one in Them. Hence, if indeed Christ has taken to Himself the flesh of our body, and that Man Who was born from Mary was indeed Christ, and we indeed receive in a mystery the flesh of His body — (and for this cause we shall be one, because the Father is in Him and He in us) — how can a unity of will be maintained, seeing that the special property of nature received through the sacrament is the sacrament of a perfect unity ?

Citation: Hilary of Poitiers, “On the Trinity, Book 8.” Paragraph 13 (c.360)

Paragraph 13 is a bit clearer. Hilary is discussing what it means for Christians to be one with Christ. Hilary thinks this oneness is physical oneness, while his critics think it is solely spiritual oneness.

See how the argument relies on the doctrine of the Trinity? While we’ve hardly mentioned it in this series, the doctrine of the Trinity developed into its modern form in the 4th century (especially towards the latter end). If the Word became Flesh—God became man—then the spiritual can become physical. For Hilary, this must be the case.

Hilary then concludes that in taking the elements of the Lord’s Supper, we become physically one with Christ in a bidirectional manner: we are one in Christ and Christ is one in us.

And, guess what? Hilary calls it a mystery! This is understandable, as the logical consequences of each person being physically one with Christ are, shall we say, a bit untenable.[1] Is the Word made flesh in all Christians as well as it was in Christ because of the Lord’s Supper? That appears to be what Hilary is saying.

Is this The Real Presence and Transubstantiation? Not really. The discussion is more about how the Trinity physically manifests itself in our own flesh, rather than the bread and wine being literally Christ’s body. Even here, it isn’t completely clear how spiritually vs physically Hilary is suggesting. It’s a bit vague and mysterious.

Let’s keep reading:

Citation: Hilary of Poitiers, “On the Trinity, Book 8.” Paragraph 17 (c.360)

As we saw in Part 24: Cyril and Part 31: Ambrose, Hilary’s doctrinal developments were being actively resisted and opposed. Hilary calls his opponents “heretics,” but it is just as likely that they thought that he was the heretic. In any case, the presence of vocal opposition in these cases shows that these were not universally held ideas. Of course, we know this because these ideas did not exist in the early writers: all originated after 300 years.

Even across the apostatizing church, where body and blood of Christ were now being sacrificed, they were still viewed as symbols—even by Cyril in 350, Serapion in 353, Apostolic Constitutions in 375-380, Macarius the Elder in 390 and Chrysostom in c.400—Hilary’s ideas were radical and novel even among those pushing for the changes.

It is reasonable to conclude that Hilary drew false equivalences between (1) the word made flesh, (2) Christ being in bidirectional unity with us, and (3) Christ offering his body and flood in the Lord’s Supper. I’m not sure how many Roman Catholics would even agree with Hilary’s views, but who knows!

We should observe also that Hilary—in his work entitled “On the Trinity”—is making an argument about the Trinity from the example of the Lord’s Supper. He isn’t making an argument about the Lord’s Supper from the example of the Trinity. It takes Hilary’s words out of their proper context to making strong inferences about his views on the Lord’s Supper.

In any case, Hilary makes clear that while we are corporeally and naturally united with Christ, what this looks like is still an unexplainable mystery. IMO, Hilary is using the mystery defense to make his illogical viewpoint immune to counterargument, that is, he is engaging in fallacious special pleading.

Citation: Hilary of Poitiers, “On the Trinity, Book 8.” Paragraph 15 (c.360)

See how Hilary speaks of the “nature” of deity. If deity has a nature, what really can we conclude of the “nature” of flesh? To what extent does flesh mean physical? Hilary did not use the word physical, he used flesh. I think the Roman Catholic is obligated to first prove that Hilary is actually making an argument about physical nature—rather than some other sense—before he can argue that Hilary is actually altering the ancient liturgy.

Hilary contrasts deified nature of Christ in the Father with the nature of us in Christ by birth, implying that our unity with Christ is not deified/spiritual. What a strange concept! Moreover, Hilary here explicitly states that we dwell with the Father in our flesh, even as Christ dwells in the Father in his deified nature. Since the Father in the Trinity was never made physical flesh, Hilary must almost certainly not be talking about a physical reality.

Frankly, Hilary’s argument doesn’t make sense if you assume him to be talking about being physically present. I simply do not see transubstantiation in Hilary, but I do see the attempt at doctrinal innovation nonetheless.

Speaking of mysteries, notice how Hilary conflates “mystery” and “sacrament”, precisely as we saw with Jerome (with the Latin vulgate) and Ambrose (in his highly influential writings). Hilary, writing in Latin around 360, shows that this view had been in development for some time. Wikipedia agrees:

Citation: “Hilary of Poitiers: Reputation and veneration .” Wikipedia

It appears that Hilary strongly influenced the Latin-speaking church before Ambrose, Augustine, and Jerome. I’m not sure if Hilary was the first to explicitly conflate these two terms, but his influence in having done so is undeniable.

Recall in our summary of this conflation in Part 31: Ambrose of Milan:

The Latin word “sacramentum” (or “sacrament” in English) is the Latin word meaning “sacred oath, vow, or pledge” and derives from the military oath witnessed by the gods. Wikpedia explains the etymology:

The Wikipedia description reflects the common Roman Catholic understanding, but notice how it is obviously wrong. The Latin word sacramentum is not derived from the Greek word mysterion. This makes no sense at all. Latin predates the New Testament by centuries.

The word sacramentum—meaning a sacred legal oath or vow before the gods—was part of the ancient Roman law long before the time of Christ. The sacred and holy nature of sacramentum comes from the ancient Latin in Roman law, because the Roman oaths were vows before the Roman gods. The word was not derived from the Greek.

As another Wikipedia article notes, sacramentum only began to take on the non-Christian meaning of “religious initiation” in the writings of Apuleius—a Latin Platonist philosopher—in the second century. It is within this context that Tertullian—in the late 2nd century—would use the word, the first Christian writer to use mysterium and sacramentum together in the same writing.

By contrast, the Latin word “mysterium” and the English word “mystery” are transliterations of the Greek word “musterion.” Like the word “eucharist”, they are not translations. To wit:

The Greek word mustērion (#3466 μυστήριον) is translated as “sacred secret” in the REV Bible (and Rotherham’s Emphasized Bible) because that is what mustērion actually means and refers to: a secret in the religious or sacred realm.

Although many English versions translate mustērion as “mystery,” that is not a good translation. Actually, “mystery” is not a translation of mustērion at all; it is a transliteration of it—simply bringing the Greek letters into English and not translating the word at all. The English word “mystery” is a mistranslation of mustērion because in English a “mystery” is something that is incomprehensible, beyond understanding, and unknowable. The orthodox Church refers to things such as the Trinity or transubstantiation as “mysteries” because they cannot be understood. In contrast to a “mystery,” a “secret” is something that is known to someone but unknown to others. The password on a computer is a “secret,” not a “mystery,” because the owner of the computer knows it. Similarly, God has revealed his “sacred secrets” to the Church via the Bible, and Christians are expected to know them. They are not “mysteries.”

Translating mustērion as “mystery” in English Bibles has caused many problems in the Church. The biggest problem is that many false and illogical doctrines have been foisted upon Christians, who are told not to try to understand them because they are “mysteries.”Another problem is that people who are convinced that the things of God are mysterious quit trying to understand them and so remain ignorant of many truths that God wants every Christian to know.

The proper translation of “mustērion ” is a “sacred secret” not (as in Latin and English) a “mystery.” A sacred secret is knowledge that is revealed by divine revelation (e.g. the gospel of Jesus Christ). It is not a vow or pledge.

Tertullian talked about the sacred secrets of the (pagan) faith that were revealed and he talked about the sacraments as initiation rites—as per Apuleius’ usage—into the faith. He even talked about those things in relation to one another, after all it is through the initiation into the faith that one gains access to the sacred secrets. But he never equated those things.

When Hilary referred to “the mystery of the sacraments,” he wasn’t referring to the sacred secrets revealed to new initiates to the faith. He wasn’t even talking about sacred secrets or initiation rites. Hilary had departed completely from Tertullian.[2] Between the mid-2nd and mid-4th centuries, the word sacramentum had lost the distinct sense of an initiation rite, vow, or pledge and taken on the more general meaning of “religious rite” because the legal practice had changed:

Citation: A.D. Nock, “The roman army and the Roman religious year”, Harvard Theological Review 45 (1952:187-252).

When Tertullian talked about the sacramentum he had in mind an initiation rite—baptism and one’s first thanksgiving tithe offering—based on the Roman military oath of allegiance before the gods. When Hilary talked about the sacramentum he had in mind repeating religious rites—the mysterious underpinnings of his weekly religious rite ‘Eucharist.’

Hilary could not rationally justify his argument, so he appealed to the “mystery of the sacraments.” He hid his novelty as something sacred that is ultimately forever mysterious: not able to be—or meant to be—fully known or explained. By “mystery of the sacraments, ” he clearly didn’t view the sacraments acts of new initiates to the faith that reveal to them the sacred secrets of the faith, but in fact the opposite: sacraments were rituals that established Christians performed regularly without being able to understand or explain their mystery.

Pay special note to how this worked. Tertullian’s pagan mysteries were sacred secrets revealed only to the initiated. The sacraments that he spoke of were Christian initiation rites that gave the Christian access to knowledge of Christ. But, the meaning of sacrament changed from being a one-time rite to being ongoing. The initial rite of the ancient church revealed the secrets of the faith. Being initiated gave one access to the sacred secrets. But nobody needs to repeat a rite to gain access to secrets one already possesses, for that knowledge was already revealed the first time the rite was performed. So when sacrament became a repeated rite, the word mystery took on a mystical meaning to account for the repetition, as if by repeating the ritual new sacred secrets were mysteriously revealed.

This change in the language usage of the church was driven by a change in the military practice![3]

In the New Testament, the mysteries are sacred secrets about the gospel and the saving work of Christ through grace, which has nothing at all to do with rites. But due to language development, this was twisted into something completely different. The New Testament doesn’t mention sacraments—initiation rites of sacred pledges and vows. The 4th-century concepts of mystery and sacrament would have been completely unknown to a 1st-century Christian.

Hilary’s statement “mystery of the sacraments” had the effect of tying the two concepts together conceptually, as if sacraments were mysteries (this is rather plainly stated by Hilary) and mysteries were sacraments (this is more of an implication). Ambrose would do the same thing when he talked about the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, the sacramental bread and wine, and the mysterious power of transformation. But it would be Jerome who would explicitly translate the Greek word mustērion directly into the Latin sacramentum in the Vulgate.[4] Whether or not Hilary meant to treat mystery and sacrament as fully synonymous, that was ultimately the effect his conflation would have only two decades later.[5]

The conflation of mystery and sacrament turned the saving work of God by grace into ritual observances. It is the origin of Roman Catholic sacramental system of works-righteousness. The Eucharist became a rite by which grace—in the form of a propitiatory sacrifice for the remission of sin—was dispensed.

It’s not clear at all that Hilary’s liturgy is even remotely compatible with the Roman liturgy of the 6th or 7th centuries, but his innovations causally led to it nonetheless. This is analogous to what we noted in Part 16: Apostolic Constitutions and Part 30: John Chrysostom. The doctrinal innovations of Roman Catholicism developed out of the highly influential newly innovated false doctrines of the men who preceded them in the late 4th-century when Roman Catholicism first arose.

The underappreciated consequence of no church writer in the first 300 years offering Christ’s body as sacrifice, is that all the Roman Catholic Church’s doctrinal innovations developed from intermediate heresies that were neither ancient nor orthodox.

Footnotes

[1] And yet it is just as untenable to say that the bread and wine are bread and wine in appearance only while being literally and physically body and blood in substance. Hilary is promoting a kind of transubstantiation of people, where each person is also Christ in substance, because Christ is really, actually, literally present physically in each Christian, just as he is in the bread and wine.

[2] It is ironic that Hilary departs from Tertullian in his work “On the Trinity.” Just as Tertullian was the first Latin writer to use mystery and sacrament together, he was also the first to use the word “trinity.” Hilary was almost certainly taking Tertullian’s use of “mystery”, “sacrament”, and “trinity” and developing all of them.

[3] This is the same way that control of language (e.g. pronouns; “cis”) introduced changes in favor of gender politics into the modern church.

[4] The New Testament definitely had rites—baptism, thanksgiving, and the Lord’s Supper—but these were merely rites. Sacrament is a term-of-art that has much more linguistic and theological baggage than merely saying “this is a thing we do as part of our religious practices.” For example, equating rites with sacraments had the effect of turning them into sacred vows or pledges before God, while equating rites with mysteries had the effect of making them spiritually mysterious, unknown, and unexplainable, as well as associating rites with saving grace.

[5] The idea that church doctrine was a mystery that could never be explained would have the side-effect of encouraging “blind faith” in seekers as a replacement for knowledge, intellect, validation, and informed trust (e.g. the Bereans). This would be used to justify the authoritarian Roman Catholic Church.

Pingback: Changing Language

Pingback: Sacraments, Part 1: Divisions

Pingback: Sacraments, Part 2: Tertullian