The original liturgy:

The Roman liturgy:

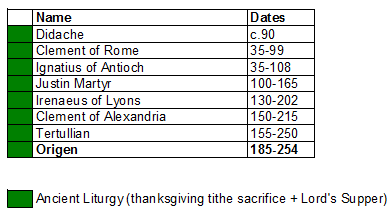

Origen

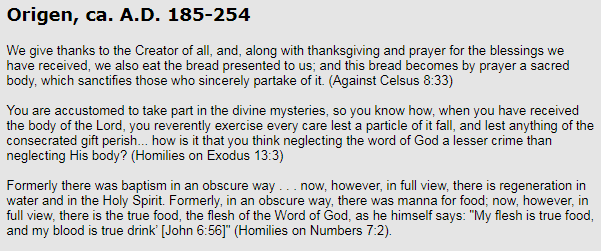

Let’s start with the final quote before examining the others. There Origen is very clear:

Formerly, in an obscure way, there was manna for food; now however, in full view, there is the true food, the flesh of the Word of God, as he himself says:

Citation: Origen of Alexandria, “Homilies on Numbers 7:2.”

Origen identifies the flesh of Christ as the Word of God and cites John 6—on the bread of life from heaven—to illustrate the metaphor. This is just as we examined in Part 7: Clement of Alexandria and Part 9: Tertullian. This explanation was the reason behind this series.

For Origen, manna from heaven as a symbol of the Word of God was obscure. There was nothing obscure about manna as literal food to be eaten. The Hebrews were not confused about whether or not manna—literal bread from heaven—could be eaten. Origen clearly believes that manna was a figure, symbol, or type of Christ’s flesh, that is, the Word of God.

Now, let’s move to the first quote. Origin simply calling it “a sacred body” does not tell us whether or not we are dealing with a metaphor, as the grammatical construction is equivalent either way. Fortunately, we have a lot of context that we can look at.

In an earlier chapter, Origen speaks of the pure sacrifices made by Christians…

and by the Psalmist,

And the statues and gifts which are fit offerings to God are the work of no common mechanics, but are wrought and fashioned in us by the Word of God, to wit, the virtues in which we imitate the First-born of all creation, who has set us an example of justice, of temperance, of courage, of wisdom, of piety, and of the other virtues.

Citation: Origen of Alexandria. “Against Celsus.” Book 8. §17

…alluding to the pure and true sacrifice spoken of by Malachi and by Jesus to the Samaritan woman (as we discussed in Part 8, Interlude). Indeed, elsewhere Origen spoke of both together:

God, therefore, dwells neither in a place nor in a land, but he dwells in the heart. And if you are seeking the place of God, a pure heart is his place. For he says that he will dwell in this place when he says through the prophet:

Citation: Origen of Alexandria, “Homilies on Genesis.” Homily 13, §3)

Our sacrifice is from the heart. We do not offer Christ’s body as sacrifice, we offer prayers of thanksgiving from a pure heart:

…

For this reason, then, let Celsus, as one who knows not God, give thank-offerings to demons. But we give thanks to the Creator of all, and, along with thanksgiving (εὐχαριστίας) and prayer (εὐχής) for the blessings we have received, we also eat the bread presented to us; and this bread becomes by prayer (εὐχήν) a sacred body, which sanctifies those who sincerely partake of it.

Citations:

- Origen of Alexandria. “Against Celsus.” Book 8. §33

- J.P. Migne’s Patrologia Graeca (1857–1866) in vol XI, col 1565

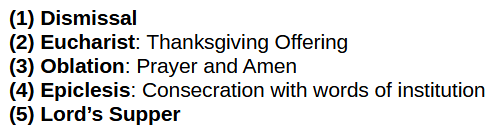

I’ve expanded the scope from FishEaters’ original citation because it is clearer that the (2-3) giving of thanks is the offering of the first fruits—the Eucharist—for the benefit of the church. The subsequent (4) prayer that turns the bread into a sacred body is the consecration or epiclesis.

For Origen, the tithe offering is the Eucharist that is offered to God by prayer, while the Lord’s Supper begins with a prayed consecration over the elements from the Eucharist that were previously offered to God. This is further confirmed in the very next chapter:

Citation: Origen of Alexandria. “Against Celsus.” Book 8. §34

And again later in the same work:

Citations:

- Origen of Alexandria. “Against Celsus.” Book 8. §57

- J.P. Migne’s Patrologia Graeca (1857–1866) in vol XI, col 1604

As have various other patristic writers, Origen speaks of the (1-3) sacrifice of the Eucharist—as tithes, firstfruits, thanksgivings, and prayers—while making no mention of either the (4) consecration or the (5) Lord’s Supper.

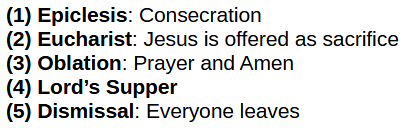

Now, let’s look at the middle quotation by FishEaters. It is notable that as Origen speaks of the (4-5) celebration of the Lord’s Supper, the (1-3) sacrifice of thanksgiving is conspicuously absent. Whether or not Origen thought the body and blood of Christ were literally present, he isn’t describing a sacrifice or offering. This is true not only in his Homily on Numbers, but the separation in the liturgy is even more clear in his Homily on 1 Corinthians:

Origen: Fragment 34 on 1 Corinthians — Robertson, A., D.D., LL.D. and Plummer, A., M.A., D.D., The International Critical Commentary on the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments: First Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians, Briggs, Charles Augustus, D.D., ed (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons (1911)) 135

There is no mention of thanksgiving. It is the consecration. The invocation. It is the Epiclesis.

…

When Origen then describes the distribution of the bread which “becomes by prayer (εὐχήν) a sacred body,” it is also clear from his own commentary on 1 Corinthians 7:5 that he is referring to the Epiclesis, or the “invocation (έπικέκληται) of the name of God and of Christ and of the Holy Spirit” over the elements that have just been used in the Eucharist offering (Fragment 34, Robertson & Plummer, 135).

…

So obvious are Origen’s two separate liturgical acts —”thanksgiving and prayer” as the Eucharist, and a “prayer” as the Epiclesis—that the Latin translator (Roman Catholic Basilios Bessarion, d. 1472) rendered the first reference to “prayer” as “precibus,” or “supplication,” and the second reference to “prayer” as “orationem,” as in “spoken words” (Migne, P.G. vol XI, col 1666). Likewise, Dr. Franz Weiland (1906), in his Mensa und Confessio: Studies on the Altar of the Early Christian Liturgy stated plainly that Origen “precisely distinguishes between ‘offering’ and ‘consecration’,” which is to say, between the Eucharist and the Epiclesis. (Weiland, Mensa und Confessio (Munich: Verlag der J. J. Lentner’schen Buchhandlung (1906) 56).

Citation: Timothy F. Kauffman “The Collapse of the Eucharist, Part 3.”

As we see many times throughout the series, there is no evidence of the Roman liturgy in the testimony of the patristic writers. But, as with Part 3: Justin Martyr, Part 5: Clement of Rome, and Part 6: Irenaeus of Lyons we find that once again translators and commentators have obscured or mistranslated the text in order to give it a Roman twist. Kauffman explains:

But that has not stopped the translators, who have been especially interested in proving that Origen’s Eucharist was in fact Consecratory. Maurice De La Taille, S.J., in his Mystery of Faith: Regarding The Most August Sacrament And Sacrifice Of The Body And Blood Of Christ, lacking any evidence at all from Origen, simply insists,

Edward J. Kilmartin, S.J., of Weston College School of Theology, likewise insisted that

and adds this footnote as evidence:

(Theological Studies, “Sacrificium Laudis: Content and Function of Early Eucharistic Prayers,” Volume: 35 issue: 2, page(s): 268-287 (May 1, 1974), emphasis added).

Now, regarding the second quote, here is the selected quotation that FishEaters provided:

Citation: Origen, “Homilies on Exodus.” Homily 13, §3

First, many Roman Catholics argue that it is only proper to receive bread on the tongue. But for Origen, the bread is handled by the hands of the laity! As the bread is received (or passed?) among the faithful, those that hold (or pass?) it should be slow and careful, so as not to drop any on the floor. As we’ve seen throughout this series, not only were the consecrated elements holy, but so too was the entire unconsecrated eucharist holy. A reverent mode of conduct is correct in the ancient liturgy.

Second, since Origen’s eucharist sacrifice is separate from his Lord’s Supper, even if Origen should be interpreted here as referring to a literal body—and it should not, as we will see below—the Roman liturgy would still not be present, for in Origen’s Eucharist, Christ’s body was not offered as a sacrifice. Indeed, early in that same document, Origen notes that…

let that soul, I say, have further in itself also an immovable altar on which it may offer sacrifices of prayers and victims of mercy to God, on which it may sacrifice pride as a bull with the knife of temperance, on which it may slay wrath as a ram and offer all luxury and lust like he-goats and kids. But let him know how to separate for the priests even from these ‘the right arm’ and ‘the small breast’ and the jaws, that is, good works and works of the right hand (for let him preserve nothing evil); the whole small breast, which is an upright heart and a mind dedicated to God and jaws for speaking the word of God.

Citation: Origen, “Homilies on Exodus.” Homily 9, §4

…what we offer as sacrifice is prayers from a pure and upright heart.

Third, since this is from Origen’s Homilies on Exodus, to what in Exodus is Origen referencing? How does it pertain to the Lord’s Supper? Timothy F. Kauffman’s comment helpfully provides that context:

Noting that scarlet receives the double emphasis in this verse, Origen goes on, saying,

…

I wish to admonish you with examples from your religious practices. You who are accustomed to take part in divine mysteries know, when you receive the body of the Lord, how you protect it with all caution and veneration lest any part fall from it, lest anything of the consecrated gift be lost. For you believe, and correctly, that you are answerable if anything falls from there by neglect. But if you are so careful to preserve his body, and rightly so, how do you think that there is less guilt to have neglected God’s word than to have neglected his body?

Yes, it is good that you take care of the elements, he says, but you have neglected God’s Word. Does Origen go an and say, “Scripture should be held in as great honor as the sacrament of Christ’s body”? No he does not. He says,

…

Let us see, therefore, why he said “scarlet doubled.” That color, as we said, indicates the element of fire. Fire, however, has a double power: one by which it enlightens, another by which it burns.

…

Let us see, therefore, how we can offer that doubled fire for the building of the tabernacle. … God, therefore, says to you also what he said to Jeremiah: “Behold I have made my words in your mouth as fire.”

In other words, you show reverence and caution when you distribute the element, but what deserves double that veneration and care is the preaching of the Word of God. So no, Origen does not say, as your source has made him to say, “the Scripture was held in as great honor as the sacrament of Christ’s body.” In fact it received double the honor.

FishEaters’ shortened quotation completely inverts the actual meaning of the passage, even as Origen was making the point that the bread—which Christ identified as the Word of God—represents a double portion of the power of the Word of God.

Of all the Words of God, what could be more powerful than the Gospel itself, of which the bread and cup are symbols? While all scripture is God-breathed, it is specifically the Words of Christ from the Father that lead to eternal life.

With this in mind, we should all consider the consequences of what happened to Christianity when the bread and body changed from Origen’s double portion of the Word of God to Roman Catholicism’s literal flesh and blood of Christ.