The original liturgy:

The Roman liturgy:

Apologetics

Perhaps the most famous quote by any Roman Catholic apologist is the one stated by Cardinal John Henry Newman:

There is a general view among Roman Catholics that all evidence points to Roman Catholicism. Their church teaches them that their church has an unbroken “apostolic succession” that goes back all the way to Peter in Rome. It teaches that every heresy is a dead-end, but that those heresies crop up repeatedly (i.e. definitely no unbroken succession of true churches that protested before Luther’s protest-ant). Meanwhile, they are taught that their own traditions are infallibly apostolic, no matter what. This spin on history is so common that virtually every Protestant agrees that the apostolic church ran through Rome!

This series was inspired by a comment from Bardelys the Magnificent:

In my opening to this series, I responded:

How can it be that the same exact quotations are used to defend categorically different beliefs? The reason is simple: Roman Catholics just assume that any reference to the Eucharist or Lord’s Supper is that described by the Roman Catholic Church in their Roman liturgy. They rarely bother to actually check, and when they do they cannot help but insert the meanings of their own religious jargon into the quotations they are referencing. In this interlude, I will demonstrate this from the quote repository at Church Fathers’ “The Sacrifice of the Mass.”

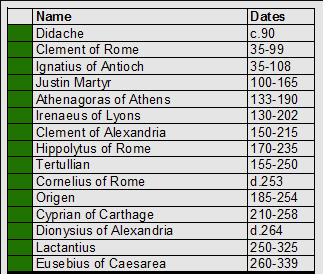

The Early Writers

Recall how, at the start of the series, we made the following bold claim:

Church Fathers gives five sources during that period. By contrast, we’ve examined 15 writers during that period…

…including all five that Church Fathers lists!

The Didache

Notice that the word Greek word “Eucharist” is shown transliterated and capitalized, instead of properly translated as “thanksgiving,” which is what the word means. This is the first clue that the Roman Catholic has done something wrong. The Didache is literally saying that on the Lord’s Day, they break bread and offer the thanksgiving.

The Roman Catholic reads this and thinks “Oh, they are offering the Eucharist, the sacrifice of the body and blood of Jesus.” But he is bringing his prior understanding into the text. It is eisegesis. The text says “the thanksgiving”, which is sacrificial prayer of thanksgiving for the tithes. Nowhere in the Didache is Christ’s body offered as a sacrifice. Indeed, the words of institution and the Lord’s Supper are absent entirely.

The Roman Catholic hasn’t even bothered to check his references, or he’d know what the thanksgiving was referring to:

The Didache is quite plain: the prophesy of Malachi is fulfilled in the prayer of thanksgiving offered for the tithe.

The banquet mentioned by the Didache is not the Lord’s Supper, but the feast for the whole church to feed those in need, which is taken out of the tithe. Quote mining misses this important context. When this banquet was also mentioned by Hippolytus, one scholar dismissed it:

Citation: Burton Scott Easton, “The Apostolic Tradition of Hippolytus.” Cambridge University Press (1934) p.74

Roman Catholics see the banquet mentioned and can only see the Lord’s Supper. They simply do not understand the “primitive custom” of having a corporate meal out of the thanksgiving—the Eucharist. Hint: 1 Corinthians 11:34.

If you read further…

…you can see how Easton agrees with the heretical Apostolic Constitutions and with those who redacted Hippolytus during their translation to other languages! We’ve seen this type of fraudulent mistranslation on a number of occasions in this series. This is also similar to how the Latin Vulgate came to supersede the original text of the Bible. Thus is the banquet found in the Didache suppressed and replaced with the later Roman novelty, as if the former were a quaint tradition and the latter deeply apostolic.

For more information, see Part 2: The Didache.

Clement of Rome

The Roman Catholic sees the word “sacrifice” and says

But if they had been paying attention when they read the Didache, they’d know precisely how wrong this is. Clement is referring to the thanksgiving, the tithe offering.

For more information, see Part 5: Clement of Rome.

Ignatius of Antioch

Notice that the word Greek word “Eucharist” is shown transliterated and capitalized, instead of properly translated as “thanksgiving,” which is what the word means. This is the first clue that the Roman Catholic has done something wrong. Ignatius is literally saying that we all have the same thanksgiving observance: every congregation brings its tithes to the altar in a sacrifice of thanksgiving in prayer, and from out of those gifts come the bread and wine used in the observance of the Lord’s Supper.

The Roman Catholic sees all the right words together: altar, sacrifice, body, cup, blood, and thanksgiving and thinks…

…but the Roman Catholic is just seeing what he wants to see. This is quite illustrative. The Roman Catholic is just looking to check off boxes: seeing the right words and assuming that those words mean the same thing that they mean to the Roman Catholic. This is a woefully inadequate way to evaluate historical writings.

In the works not cited here, Ignatius makes plain what he means. It is unlikely that the Roman Catholic understands the relevance of the heresies to which Ignatius wrote against, and so interprets Ignatius against a medieval mirror instead.

For more information, see Part 4: Ignatius of Antioch.

Justin Martyr

Notice that the word Greek word “Eucharist” is shown transliterated and capitalized, instead of properly translated as “thanksgiving,” which is what the word means. This is the first clue that the Roman Catholic has done something wrong. Justin Martyr is literally saying that the bread of the thanksgiving and the cup of the thanksgiving are offered as sacrifice. What are the bread and cup of the thanksgiving? They are the elements taken out of the tithes of bread and wine (and, as we’ve seen elsewhere, other agricultural products such as oil) that are given as gifts in the sacrifice of thanksgiving.

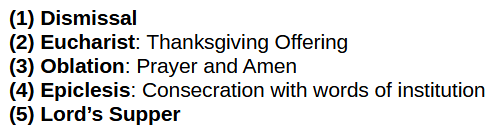

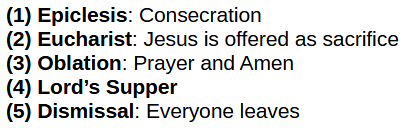

Had the quote mining been replaced by a more complete study of Justin Matry’s works, it would become clear that the sacrifices that Justin Martyr has in mind are prayers, words of thanks, offerings of tithes and firstfruits, true and spiritual praises, and hymns. Moreover, the order of Justin Martyr’s liturgy is thus: (1) Dismissal—(2) Eucharist—(3) Oblation—(4) Consecration—(5) Lord’s Supper. Recall what the Catholic Encyclopedia said:

Citation: Adrian Fortescue, “The Origin of the Mass.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol 9. (1910)

The Roman Catholic liturgy is not found in Justin Martyr.

For more information, see Part 3: Justin Martyr.

Cyprian of Carthage

Here is the quotation that Church Fathers gave:

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Letter 62:14″ [A.D. 253]).

Despite appearances, Cyprian does not describe a Roman Catholic liturgy. To answer this, I will let Timothy F. Kauffman explain:

Do you want to know what Cyprian meant? Some Christians were only serving water instead of wine so that they could avoid persecution. They were being detected as Christ followers by the wine on their breath. Cyprian told them that they had to use wine. If Jesus could offer himself as a sacrifice to the death, at the very least you can use actual wine as Christ commanded in commemoration of his sacrifice, even if this puts you at personal risk. How can a priest imitate and function in the place of Christ if he serves water? He cannot.

This isn’t the meaning that the Roman Catholic thinks when he quote mines this. Don’t believe me? Go read the three paragraphs that precede the one quoted, and you’ll see for yourself how this quote badly misrepresents what was actually written. It has nothing to do with the Roman liturgy.

Its worth noting that this quote is often mined out of context. Church Fathers cites this as Letter 63 (it is letter 62). The commenter that Tim Kauffman is responding to thought it was part of “Letter to the Ephesians.” The “Real Presence eucharistic Education and Adoration Association” makes the same error. The Roman Catholic apologists are not even checking their sources, let alone reading them to ensure that they say what is implied!

This comment by Tim Kauffman could just as easily been addressed to Church Fathers:

This is the problem with Roman Catholic apologists: they have no idea what they are talking about, and so they misrepresent the evidence. If they were more honest, like the Catholic Encyclopedia, they’d admit that the Roman liturgy doesn’t exist until the 6th or 7th century. But if they thought about what that meant, they might no longer be Roman Catholic. It’s much easier to stick your head in the sand and mine quotes.

Without a knowledge of context, you cannot understand what Cyprian was saying. For example, how does the Roman Catholic respond to this quote from the same document?

Does the Roman Catholic agree with Cyprian that the we are literally joined together as one with Christ in the unconsecrated bread and wine? I doubt it.

For more information, see Part 11: Cyprian of Carthage.

The Transitional Writers

When the Catholic Encyclopedia declared that the Roman Liturgy cannot be found in its complete form until the 6th or 7th century, we became deeply suspicious of individual apologists who try to claim otherwise. And so we are unsurprised that the four early writers examined above do not actually describe a Roman liturgy.

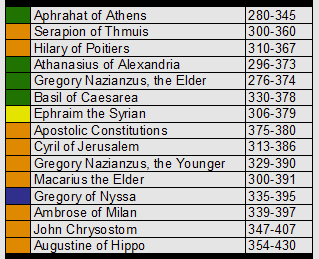

But, now we’ve reached the transitional period that we are examining in this series, from the middle of the 4th century until Augustine in the 5th century, when the Roman liturgy began its development. Church Fathers discusses seven writers:

- Serapion

- Cyril of Jerusalem

- Gregory of Nazianzus (the Younger)

- Ambrose of Milan

- John Chrysostom

- Augustine

We discuss each of these sources, plus 9 others in our series.

Notably missing from Church Fathers’ list are the other quotes from the various writers who repudiated the Roman Catholic novelties. These quotes are more-or-less selected because they describe what appears to support the Roman liturgy. But as we’ve seen throughout the series, none of them describe the Roman liturgy exactly. All describe another version.

This is a common Roman Catholic tactic, to only cherry-pick quotes that support the Roman liturgy and to act as if the contrary evidence does not exist. But in this series, we do the opposite: we go through it all, whether or not it confirms our bias. In doing so we’ve found a wide range of opinion among the writers in this period. If you examine these sources for yourself, you are quite likely to come to the same conclusion: the writers in this period did not agree with each other, the ancient liturgy, or the later medieval Roman liturgy. We conclude, therefore, that it was a period of transition, a period of changing liturgical forms.

Serapion

As the Roman Catholic suspects, Serapion really did sacrifice Christ’s body and blood. Just not literally.

For more information, see Part 29: Serapion of Thmuis.

Cyril of Jerusalem

As the Roman Catholic suspects, Cyril really did sacrifice Christ’s body and blood. And it was a sacrifice of propitiation. But the elements were not taken literally. Cyril didn’t believe in transubstantiation, which is why he called it bloodless. The blood was symbolic, not literal.

The Roman Catholic’s “unbloody” sacrifice, which purportedly contains Christ’s actual blood, is not the same as Cyril’s “bloodless” sacrifice. The Roman Catholic sees in “bloodless” what he wants to see, but which is not actually there.

The Roman Catholic also leaves out the important context that Cyril had to actively defend his novel viewpoints from critics who disagreed with him.

For more information, see Part 24: Cyril of Jerusalem.

Gregory of Nazianzus (the Younger)

It is funny that they cite Gregory the Younger and not Gregory the Elder, for the Roman liturgy is not found in the Elder’s beliefs.

Regardless, Gregory the Younger described the body and blood of Christ as a sacrifice for the propitiation of sin. As with Cyril, he referred to it as a bloodless sacrifice. But like Cyril and Gregory the Elder, bloodless meant symbolic, not “unbloody” as in the Roman Catholic presumptions.

For more information, see Part 25: Gregory Nazianzus.

Ambrose of Milan

We agree with the Roman Catholic that Ambrose offered Christ’s body as a sacrifice. What Church Fathers leaves out is that he had to actively defend his novel viewpoint from critics.

For more information, see Part 31: Ambrose of Milan.

John Chrysostom

The quotes Church Fathers provides from John Chrysostom are too long to quote here. You can read more about John’s Jekyll and Hyde viewpoints in Part 30: John Chrysostom.

Augustine

We have not yet discussed Augustine, but we agree with Church Fathers that Augustine diverged from the ancient liturgy towards a more explicit Roman liturgy, but nevertheless not a liturgy that matched the eventual Roman liturgy.

On Apologists

Roman Catholic apologists have a problem: they don’t have history on their side. This analysis of Roman Catholic quote mining made this abundantly clear. This entire series is based on the quote mining from FishEaters, which is just as misguided as that of Church Fathers.

What this interlude has illustrated is that Roman Catholics understand the early church writers based on their Roman Catholic understanding. They do not understand the early church writers based on any kind of analysis of the historical record. It simply doesn’t matter what the historical record says, because it is required to conform to the Roman Catholic understanding. But, if Roman Catholics were intellectually honest, they’d admit that…

The history of Roman Catholicism more-or-less starts in 350AD, not 300+ years earlier in 30AD.

On Eisegesis

In FishEaters’ “The Eucharist” she says, in an attempt to insert transubstantiation into John 6:

AND

How can both of these verses be true if understood in the sense that Protestants understand them? Is He schizophrenic? A liar? A contradicter of His own words? Did He change His mind in between verses 58 and 63?

It is as Timothy Kauffman explained:

John 1: come and believe to have everlasting life and be raised up at the last day.

John 2: come and believe to have everlasting life and be raised up at the last day.

John 3: come and believe to have everlasting life and be raised up at the last day.

John 4: come and believe to have everlasting life and be raised up at the last day.

John 5: come and believe to have everlasting life and be raised up at the last day.

John 6:1-47: come and believe to have everlasting life and be raised up at the last day.

John 6:48-71: IF YOU DON’T BELIEVE IN TRANSUBSTANTIATION AND WORSHIP THE EUCHARIST YOU’RE GOING TO PERISH IN HELL FOR ALL ETERNITY, AND MARK MY WORDS SOME DAY THE CHURCH I ESTABLISH ON PETER THE ROCK, WITH THE HELP OF HIS INFALLIBLE SUCCESSORS AND THE APPARITIONS OF MARY, IS GOING TO CHASE YOU DOWN AND TORTURE YOU AND BURN YOU ALIVE AT THE STAKE IN THE INQUISITIONS UNLESS YOU BOW DOWN AND WORSHIP THE TRANSUBSTANTIATED BREAD AND WINE AND EXPOSE THEM FOR PERPETUAL ADORATION, YOU PROTESTANT HERETICS!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

John 7: come and believe to have everlasting life and be raised up at the last day.

Honestly, “transubstantiation” is just a horrible, terrible, grotesque non sequitur imported into the narrative, and there is not so much as a hint of it in chapter 6. And as the other chapters show, Jesus does not always pause to clarify his meanings and metaphors to the satisfaction of His hearers, and even His disciples didn’t understand some of them until after the resurrection. By the plain reading of the book, John 1-7 has to do with coming to Jesus and believing in Him in order to be raised up on the last day unto everlasting life. Many metaphors are used to drive that point home. Those are the comforting words of the Good Shepherd to His sheep. The Roman Catholic interpolation in John 6 is the message of a false shepherd, the thief who would lead the sheep astray, coming only to steal, kill and destroy. Fortunately, Christians cannot and do not hear the words of the false shepherd (John 10:8).

There is no difficulty understanding what Jesus meant in John 6. He is not schizophrenic, nor a liar, nor did he contradict his own words, nor did he change his mind in between verses 58 and 63. Notice what the flesh is: “my [Jesus’] flesh” (v51, v54, v55, v56), “his [Jesus’] flesh” (v52), and “the flesh of the Son of man [Jesus]” (v53). All of these refer to the flesh of Jesus. So what is Jesus’ flesh? It is the Word of God through his doctrine and teaching, it is spiritual flesh. So when Jesus says…

…it is the spirit not the flesh (in verse 63) that corresponds to the flesh of Jesus in verses 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, and 56.

How do I know this? Because after saying that “the spirit gives life and the flesh profits nothing” he says “the words I have spoken to you are spirit and are life.” The words are spirit and life. The words.

How do I know that the flesh of Christ are his words? Because of the fact that he quoted Isaiah:

John 6:43-51 (REV)

Do not grumble among yourselves. No one is able to come to me unless the Father who sent me draws him, and I will raise him up at the last day. It is written in the prophets, And they will all be taught by God. Everyone who has heard from the Father and has learned, comes to me, not that anyone has seen the Father except he who is from God, he has seen the Father. Truly, truly, I say to you, whoever believes has life in the age to come. I am the bread of life. Your fathers ate the manna in the desert, and they died. This is the bread that comes down out of heaven so that a person may eat of it and not die: I am the living bread that came down from heaven. If anyone eats of this bread, he will live forever. Indeed, the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh.

Isaiah 54:13 (KJV)

“And all thy children shall be taught of the LORD.”

Isaiah 55:1-4 (KJV)

“Ho, every one that thirsteth, come ye to the waters, and he that hath no money; come ye, buy, and eat; yea, come, buy wine and milk without money and without price. Wherefore do ye spend money for that which is not bread? and your labour for that which satisfieth not? hearken diligently unto me, and eat ye that which is good, and let your soul delight itself in fatness. Incline your ear, and come unto me: hear, and your soul shall live; and I will make an everlasting covenant with you, even the sure mercies of David. Behold, I have given him for a witness to the people, a leader and commander to the people.”

Kauffman said…

…and we agree. This is not ambiguous at all: the food and drink that Jesus provides are his teachings. To eat his flesh, simply hearken diligently, incline your ear, and hear the words of Jesus. But, the Roman Catholic simply cannot see this because they cannot disconnect from what their Church has taught them. FishEaters’ difficulty in understanding how verses 51 through 56 work with verse 63 is entirely self-inflicted.