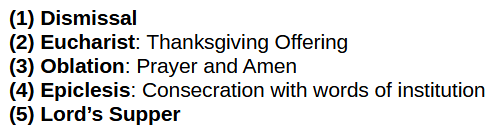

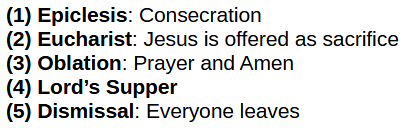

The original liturgy:

The Roman liturgy:

Ambrose of Milan

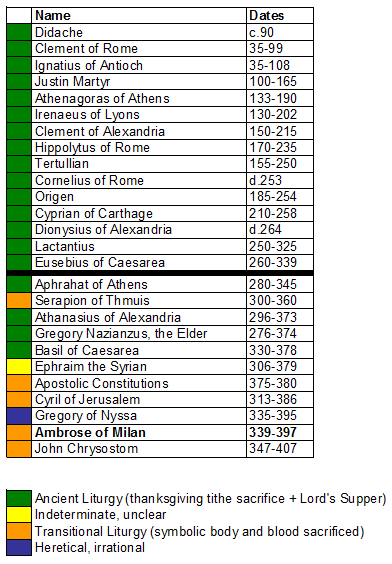

While we have seen a number of writers altering the ancient liturgy—Cyril in 350, Serapion in 353, Apostolic Constitutions in 375, Chrysostom in 400—it is Ambrose writing in 389 that is most blatant in embracing the doctrinal innovations of the newly risen Roman Catholic Church.

Citation: Ambrose of Milan, “Commentaries on Psalms 38:25.” (389) Ambrose joins those others in sacrificing Christ’s body. But, Ambrose has a lot more to say. Quotations of Ambrose are very popular among Roman Catholic apologists for reasons that will be quite obvious to readers. It is a priest’s duty to offer something, and, according to the Law, to enter into the holy places by means of blood; seeing, then, that God had rejected the blood of bulls and goats, this High Priest was indeed bound to make passage and entry into the holy of holies in heaven through His own blood, in order that He might be the everlasting propitiation for our sins. Priest and victim, then, are one; the priesthood and sacrifice are, however, exercised under the conditions of humanity, for He was led as a lamb to the slaughter, and He is a priest after the order of Melchizedek. Citation: Ambrose of Milan, “On The Faith, Book III.” §11 ¶87 It is curious that, of all things Ambrose said, Roman Catholic apologists trot out this quotation. If you click that link and read the context, you’ll see that Ambrose isn’t talking about the body and blood of Christ or the Lord’s Supper at all. He’s simply talking about Christ’s sacrifice on the cross. But the Roman Catholic reads this as if Christ sacrificed himself at the Lord’s Supper. We’ve seen this before in the Part 27: Interlude: Citation: FishEaters, “The Eucharist.” Notice FishEaters’ assumption that Christ sacrificed himself at the Last Supper. The Bible describes Christ as being a priest in the order of Melchizedek who sacrificed himself on the cross, not at the Last Supper. Forty years after Luther posted his theses, an ex-Catholic priest was charged with heresy. During his trial, he argued that Roman Catholics infused the simple word “do”… “do this in remembrance of me” …with sacrificial significance: Latimer.— “Did Christ then offer himself at his supper?” Pie.— “Yea, he offered himself for the whole world.” Latimer.— “Then, if this word ‘do ye’ [Latin: facite], signify ‘sacrifice ye’ [Latin: sacrificare], it followeth, as I said, that none but priests only ought to receive the sacrament, to whom it is only lawful to sacrifice: and where find you that, I pray you?” Weston.— “Forty years agone, whither could you have gone to have found your doctrine?” Latimer.— “The more cause we have to thank God, that hath now sent the light into the world.” Citation: John Foxe, “The Protestation of Dr. Hugh Latimer.” Foxe’s Book of Martyrs. Book II. §XVI Roman Catholics had thus mystified the simple command “you do” into “you sacrifice.” Of course, no one during the apostolic era or long after ever thought that. It’s just the word “do.” So in 1557, they burned a old man to death who failed to properly ‘understand’ the word “do” in the sense of “a priest must offer as sacrifice.” But there is no reason to accept this claim. As we’ve seen throughout this series, the church writers in the first 300 years never once offered Christ’s body as a sacrifice. They understood the word “do” to mean what the word “do” means, which is not “sacrifice.” The propitiatory acts of Christ took place solely at the cross. Take notice, then, what He said in an earlier part of His discourse. Verily, verily, I say unto you. He first teaches you how you ought to listen. Verily, verily, I say unto you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man, and drink His blood, you shall have no life in you. John 6:54 He first premised that He was speaking as Son of Man; do you then think that what He has said, as Son of Man, concerning His Flesh and His Blood, is to be applied to His Godhead? Then He added: For My Flesh is meat indeed, and My Blood is drink [indeed]. John 6:56 You hear Him speak of His Flesh and of His Blood, you perceive the sacred pledges, [conveying to us the merits and power] of the Lord’s death, John 6:52 and you dishonour His Godhead. Hear His own words: A spirit has not flesh and bones. Luke 24:39 Now we, as often as we receive the Sacramental Elements, which by the mysterious efficacy of holy prayer are transformed into the Flesh and the Blood, do show the Lord’s Death. Citation: Ambrose of Milan, “On The Faith, Book IV.” §10 ¶124-125 This quotation is particular notable because it highlights the Roman Catholic conflation of the Latin word for sacrament with the Greek word for mystery. Like Jerome (who translated the Bible into Latin), Ambrose wrote in Latin. We first mentioned this conflation in Part 9: Tertullian, for he was the first to merely use the two words together: he called baptism and the thanksgiving “sacraments” and called pagan practices “mysteries.” Citation: Darius Jankiewicz, “Sacramental Theology and Ecclesiastical Authority“ But Ambrose and Jerome would formally conflate these two words in the late 4th century, thus setting the foundation for the Roman Catholic sacramental system alongside the alterations to the ancient liturgy. Consider how this worked. In the New Testament the mysteries were the works of God’s saving grace. The mysteries were not rites, they were revealed secrets. The sacraments, under Tertullian were baptism and the thanksgiving. These were completely separate things. Sacraments were not mysteries and mysteries were not sacraments. Until they were merged and for the first time, the thanksgiving and baptism became mysteries and mysteries suddenly became rites subject to the administration of grace by priests. Thus are the Roman Catholic priesthood, the sacraments, and the Roman Catholic concept of grace inextricably linked together, starting in the late 4th century with the rise of Roman Catholicism. The conflation of mystery and sacrament turned the saving work of God by grace into ritual observances. It is the origin of Roman Catholic sacramental system of works-righteousness. The Eucharist became a rite by which grace—in the form of a propitiatory sacrifice for the remission of sin—was dispensed. Notice how Ambrose views the Lord’s Supper as a sacred pledge? Sacrament means vow or pledge. But the Bible makes no mention of sacraments, it only mentions the sacred mysteries. These mysteries are more like shared secrets: something that was hidden, but made known because it was knowable. When the word was conflated into Latin, it took on the meaning of “unknown and unknowable,” the same connotation that the word ‘mystery’ has in English: something that cannot be fully explained by its very nature. Roman Catholics view their doctrinal innovations as mysteries that cannot be explained, and so they are not required to explain them. They are simply accepted on the matter of blind faith. But the Bible never viewed the mysteries this way. The mysteries are previously unknown secrets that were revealed by Christ. The saving work of the grace of God through faith alone is not mysterious. Now that you know how Mysteries became Sacraments and Sacraments became Mysteries, you are ready to read “On the Mysteries” and “On the Sacraments” by Ambrose: Perhaps you will say, I see something else, how is it that you assert that I receive the Body of Christ? And this is the point which remains for us to prove. And what evidence shall we make use of? Let us prove that this is not what nature made, but what the blessing consecrated, and the power of blessing is greater than that of nature, because by blessing nature itself is changed. We observe, then, that grace has more power than nature, and yet so far we have only spoken of the grace of a prophet’s blessing. But if the blessing of man had such power as to change nature, what are we to say of that divine consecration where the very words of the Lord and Saviour operate? For that sacrament which you receive is made what it is by the word of Christ. But if the word of Elijah had such power as to bring down fire from heaven, shall not the word of Christ have power to change the nature of the elements? You read concerning the making of the whole world: He spoke and they were made, He commanded and they were created. Shall not the word of Christ, which was able to make out of nothing that which was not, be able to change things which already are into what they were not? For it is not less to give a new nature to things than to change them. The Lord Jesus Himself proclaims: This is My Body. Matthew 26:26 Before the blessing of the heavenly words another nature is spoken of, after the consecration the Body is signified. He Himself speaks of His Blood. Before the consecration it has another name, after it is called Blood. And you say, Amen, that is, It is true. Let the heart within confess what the mouth utters, let the soul feel what the voice speaks. What we eat and what we drink the Holy Spirit has elsewhere made plain by the prophet, saying, Taste and see that the Lord is good, blessed is the man that hopes in Him. In that sacrament is Christ, because it is the Body of Christ, it is therefore not bodily food but spiritual. Whence the Apostle says of its type: Our fathers ate spiritual food and drank spiritual drink, 1 Corinthians 10:3 for the Body of God is a spiritual body; the Body of Christ is the Body of the Divine Spirit, for the Spirit is Christ, as we read: The Spirit before our face is Christ the Lord. Lamentations 4:20 And in the Epistle of Peter we read: Christ died for us. 1 Peter 2:21 Lastly, that food strengthens our heart, and that drink makes glad the heart of man, as the prophet has recorded. Citation: Ambrose of Milan, “On The Mysteries” §9 ¶50,52,54,58 You may perhaps say: “My bread is ordinary.” But that bread is bread before the words of the Sacraments; where the consecration has entered in, the bread becomes the flesh of Christ. And let us add this: How can what is bread be the Body of Christ? By the consecration. The consecration takes place by certain words; but whose words? Those of the Lord Jesus. Like all the rest of the things said beforehand, they are said by the priest; praises are referred to God, prayer of petition is offered for the people, for kings, for other persons; but when the time comes for the confection of the venerable Sacrament, then the priest uses not his own words but the words of Christ. Therefore it is the word of Christ that confects this Sacrament. Before it be consecrated it is bread; but where the words of Christ come in, it is the Body of Christ. Finally, hear Him saying: “All of you take and eat of this; for this is My Body.” And before the words of Christ the chalice is full of wine and water; but where the words of Christ have been operative it is made the Blood of Christ, which redeems the people. Citation: Ambrose of Milan, “On the Sacraments, Book IV.” Notice how Ambrose merges the concept of mystery and sacrament? Notice that Ambrose still has the (3) “Amen” at the end of the oblation? Notice too that he has moved the (4) consecration to before the oblation, thus explicitly sacrificing the consecrated bread and wine. Notice how Ambrose argues that the bread’s very nature is changed? Yet he still calls it a “type” and “spiritual.” Even Ambrose is not yet at the doctrines of Transubstantiation and the Real Presence. Notice too that Ambrose is an apologist: he is explicitly arguing against opponents who oppose his novel sacramental and sacrificial view of the body and blood of Christ. Ambrose argues that they too should accept his changes. We also saw that in Part 24: Cyril, who also was trying to persuade people to accept his innovations. We know from history that Roman Catholics were indeed persuaded to accept the changes that these men proposed. You can read more about the conflation of mystery and sacrament in Part 34: Hilary of Poitiers.

Pingback: Changing Language

Pingback: Sacraments, Part 1: Divisions