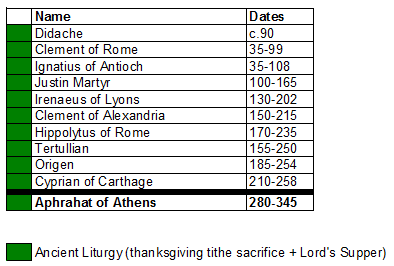

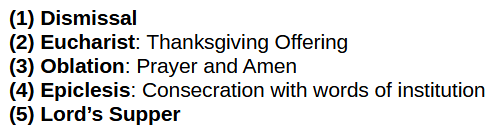

The original liturgy:

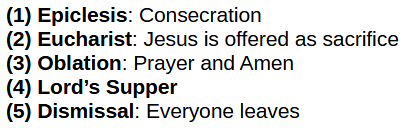

The Roman liturgy:

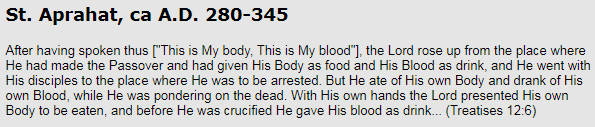

Aphrahat the Persian Sage

What more can be said about this? It’s basically just a repetition of scripture itself with some minor flourishes. Aphrahat was repeating the same metaphor that Jesus used: “this is my body” and “this is my blood.”

For sake of argument, let’s assume that Aphrahat viewed it as Christ’s literal body and blood to be consumed. We find that even then he could not have meant for it to be a sacrifice as required by the Roman liturgy:

The prophet said concerning the peoples [Gentiles] that they would present offerings instead of the people [Jews]:

Citation: Aphrahat the Persian Sage, “Demonstration 16.” 3

Hear concerning the strength of pure prayer, and see how our righteous fathers were renowned for their prayer before God, and how prayer was for them a pure offering. [Malachi 1:11] … Observe, my friend, that sacrifices and offerings have been rejected, and that prayer has been chosen instead.

Citation: Aphrahat the Persian Sage, “Demonstration 4.” 1,19

Aphrahat viewed the sacrifices that the church offered as being prayers, as in the prayer of thanksgiving—eucharist—in the tithe offering. Even if the prayer of consecration turned the elements into Christ’s actual body and blood, it still would not constitute a sacrifice, for only the prayer itself could be offered as sacrifice.

Aphrahat joins the rest of the growing list of patristic writers who saw Malachi’s prophecy as described in Part 8: Interlude as being fulfilled in the church’s thanksgiving sacrifice—eucharist—of prayer, praise, hymns, service, and the giving of tithes: Jesus, John, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Origen, and Cyprian.

But that is not the only way in which Aphrahat’s liturgy differs from the Roman liturgy:

The table is laid and the supper prepared. The fatted ox is slain and the cup of redemption mixed. The feast is prepared and the Bridegroom at hand, soon to take his place. The apostles have given the invitation and the called are very many.

Citation: Aphrahat the Persian Sage, “Demonstration 6.” Chapter 6.

In Matthew 26:29, Jesus told his diciples that he would not drink from the fruit of the vine until he returned in his Father’s kingdom. Aphrahat here describing this Wedding Feast of the Lamb, where the cup has already been mixed with water before the Bridegroom—Christ—has been seated as part of the preparations for the meal. The killing of the ox and the mixing of water are preparations for the meal. But in the Roman liturgy, the cup is mixed with water at the table, rather than in advance. Roman Catholicism erred in concluding that Jesus mixed water and wine (merum) at the table, because it didn’t understand why the water was mixed with wine.

This is another example of how the Roman liturgy diverged from the ancient liturgy. This is no minor issue either, as it was a sticking point in the conflict between the East and West before the great schism (where, ironically, both sides were wrong).

Unwatered wine is called merum. Merum is what is produced from the wine-making process of the fermentation grapes. It is the artifact of its manufacturing process.

Wine was watered before drinking to reduce its intensity and alcohol levels. People simply didn’t drink straight merum (at least on a daily basis). In the time of Jesus, the wine was mixed as part of the meal preparations, just as bread was baked before the meal and the ox was slaughtered and cooked.

Jesus didn’t bake the unleavened bread at the table. It was already baked.

Jesus didn’t mix the wine with water at the table. It was already watered.

At some point before the late-4th century, the standards for making a proper table wine had changed and water was no longer added to the wine in preparation for meals. The cultural practice had changed, and so the church leaders—Ambrose in particular—guessed… and guessed wrong to tragic consequences:

Ambrose’s late 4th century novelty, coupled with ignorance of the ancient manufacturing process of wine, led to a comical, medieval dispute between the West and the East. The West insisted erroneously that Jesus had mixed His wine at the table (He had not), and the East denied it, insisting instead that Jesus had used straight “merum sine aqua,” merum without water (He had not). Such were the combined fruits of ignorance mixed with the novel late-antique liturgizing of a common agricultural manufacturing process to make it part of the Eucharistic liturgy. Citation: Timothy F. Kauffman, “The Mingled Cup, Part 3.” (2016)

Even now, during the Roman liturgy, water is mixed with wine at the table. The Roman liturgist can make no sense of Aphrahat’s reference to the “cup of redemption mixed” alongside “the fatted ox is slain”, for he does not understand how could this be part of the preparations: “The table is laid and the supper prepared.” And so he must rationalize away, as with the other patristics, why the Roman liturgy can’t be found in the first 300 years of the church.

Even though the Protestants to this day prepare the cup ahead of time, just as was done in ancient times, the incidental matter of wine and water has no liturgical significance.

For those who remain skeptical, simply read these accounts from the Catholic Encyclopedia:

Citation: Herbert Thurston, “Liturgical Use of Water.” Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol 15. (1912)

Citation: Adrian Fortescue, “The Origin of the Mass.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol 9. (1910)

Just like Roman Catholics don’t know why their service is called the “Mass” because they’ve lost the purpose of the original (1) Dismissal—sending away the unbelievers, backsliders, and catechumens prior to the (2-3) sacrifice of the Eucharist and (4-5) celebration of the Lord’s Supper—they also don’t know why they mix water with wine because they’ve lost the original reason for doing so. If they understood, they wouldn’t be Roman Catholic anymore.

Thurston is clearly wrong: the ancient patristic writers had no trouble understanding either of these things, and pointed them out in a number of places. The issue is that the Roman Catholic has intentionally blinded himself to fact of the ancient liturgy, and so cannot see the evidence right in front of him. Because of his own assumptions, he attributes and projects his own personal confusion over the matter onto the patristic writers, who were not at all confused.

Speaking of the Dismissal and the name “Mass,” before 385AD, Ambrose wrote that the dismissal of the catechumens occurred before oblation. But after, no longer were the unbeliever and the sinning believer dismissed and not permitted to give their tithe or forbidden from being present for the Lord’s Supper. Thus did the language of “Mass” or “Ite missa est” (dismissal chant in the Roman rite) come to refer to the dismissal of the laity after the service. As the Catholic Encyclopedia notes, this name was collectively applied to the entire Eucharistic sacrifice and Lord’s Supper, from start to finish.

The origin of the name “Mass” is itself the very proof of its corruption.

You can see from the Catholic Encyclopedia account that the Catholic church has no idea why the name Mass came to be accepted. Sure, it identifies the Missa Catechumenorum, but it fails to see any significance in it. Instead, it does two things. First, it associates the ‘missa’ with the end of the service (because that’s the only thing that matches the Roman liturgy). Second, it only cites a late-4th, early-5th century writer (Augustine) and two medieval sources. None of the earlier sources that we look at in this series are used to explain the Dismissal. This is quite the omission! It is difficult to believe this was an accident. Both Catholic Encyclopedia articles couldn’t have missed the point any more than they did.

The real reason the name “Mass” was chosen was because the Dismissal was the start of the ancient liturgy. Naming things after its beginning—for example Adam and the human race; Christ and Christianity—is an incredibly common figure-of-speech. But, the Roman Catholic, being unable to discover why this name was chosen, simply assumes the Dismissal was at the end of the liturgy. It couldn’t be any more inverted from the truth.

All of this is buried under these seemingly innocent comments by Aphrahat. But, if someone is predisposed to dismiss anything that doesn’t fit their preconceptions, they’ll likely miss the not-ambiguous-at-all references that he made. In any case, as with the other patristic writers, the Roman liturgy is nowhere to be found.