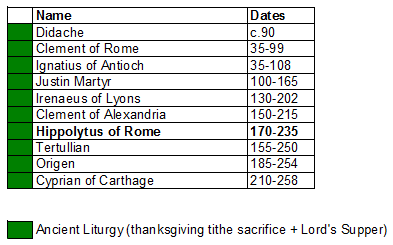

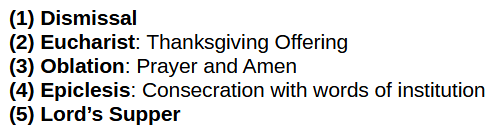

The original liturgy:

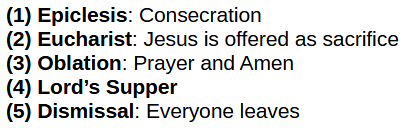

The Roman liturgy:

Hippolytus of Rome

FishEaters does not mention Hippolytus and this is not surprising. Hippolytus was a disciple of Irenaeus, whom we covered in Part 6. Unsurprisingly, Hippolytus and Irenaeus describe the same Eucharistic liturgy. As we will see, Hippolytus’ comments are a thorn in the side of the Roman liturgy.

Citations:

- Hippolytus of Rome, “Refutation of All Heresies.” Book 6, §34

- J.P. Migne’s Patrologia Graeca (1857–1866) in vol XVI, col 3258.

As we’ve seen throughout this series, Hippolytus’ liturgy also had an (2-3) offering or oblation before and separate from the (4) consecration or epiclesis. Note: There is an ambiguity in the English between “prayer” and “invocation,” so the Greek (from Migne) is added to show that two acts are being described—Eucharist and Epiclesis—not one.

Citation: Hippolytus of Rome, “Refutation of All Heresies.” Book 6, §37

Hippolytus is discussing the heretic Marcus (written of by Irenaeus) and in dong so mentions (3) the “Amen” that concludes the Oblation.

So far the comments by Hippolytus are merely typical of what we’ve come to expect throughout this series. This is about to change in dramatic fashion.

Now we turn to Hippolytus’ “Apostolic Traditions” and the Anaphora contained within. Here is an example of what Hippolytus says:

Likewise, if someone makes an offering of cheese and olives, the bishop shall say, “Sanctify this brought-together milk, just as you also bring us together in your love. Let this fruit not leave your sweetness, this olive which is a symbol of your abundance, which you made to flow from the tree, for life to those who hope in you.”

Citation: Hippolytus of Rome, “Apostolic Traditions.”

In Hippolytus we see the most explicit and detailed reference to the (2-3) Eucharist—tithe—offering that we’ve seen in the entire series so far. Not only do we see the offering of various agricultural products offered together, but we see how the liturgy itself gave different symbolic significance to each type of product.

In the Anaphora we can see Hippolytus’ (4-5) Lord’s Supper, which is unambiguously a separate act than the Eucharist (which involves, among other things, cheese):

With this in mind, what happens if you Google this? The result is here. There is something rather strange here. The first two links are expected: the full text of the Anaphora and the Wikipedia article. But by the third link, we have a Catholic apologist who, finding a distinctly anti-Roman liturgy, dismisses it utterly:

The fourth link is a rare non-Catholic source who saw in Hippolytus the ancient liturgy and repudiates the Roman liturgy: The fifth link is by Associate Professor of Theology at Holy Cross College in Notre Dame, Indiana, a Roman Catholic pastoral liturgist and historian. Woah! What does she say? But, regardless of whence the text comes, what surprised me was how the students read the text. [.] …it took them longer to see the repeated reference to Jesus as a “beloved” child or servant, the recital of salvation history, and certainly (gasp) this reference to “milk which has been coagulated,” let alone the olives, cheese, and oil (translation by R.C.D. Jasper and G. J. Cuming, 3rd rev. ed., Liturgical Press, 1990). What to make of these things? … For example, from the Apostolic Tradition (chapter 6), following a blessing of bread, wine, and oil: “Likewise, if anyone offers cheese and olives, he shall say thus: ‘Sanctify this milk which has been coagulated, coagulating us also to your love.’” Instead of claiming that this text is “wrong,” “taken out of context,” or refers to “something other than a Eucharist,” let’s appreciate the text for what it tells us: that various items might have been presented in the context of the Eucharist, that these various items were common foodstuffs, and that these items offered represented theological symbols used to interpret the Eucharist. Just as milk had been warmed, curdled, and congealed to form a delectable, soft goat cheese, so too do we desire our hearts to be on fire, changed, and born anew into a better Body, one which can be shaped by the grace of God, and serve as food for the world. Reading ancient texts is challenging—but instead of looking for what is “wrong,” or even liking them because we recognize our present in them—let’s look for what they teach us. Certainly the history of liturgical texts invites us to a feast, full of rich fare. As one of my students’ textbooks asks, how will we respond to the banquet’s wisdom (Gary Macy, Banquet’s Wisdom, OSL Publications, 2005; Proverbs 9)? This is truly astounding! I’m reminded of the line from the Wizard of Oz: “Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain!” Harmon does not want you to worry about what is “right” or “wrong” with the passage: there is something in it for everyone. There is no need to be divisive! (Does this sound familiar to any of the regular blog readers here?) Well, of course she doesn’t want us to worry about what is wrong! When the facts destroy your perspective of the liturgy—which you’ve dedicated your life and faith around—you not only don’t want to focus on the right or wrongness of it, but you want to X it out with a black marker and never think of it again. Censorship is the black mark of someone who doesn’t have history on their side. (Does this sound familiar to any of the regular readers here?) The sixth link contains this quote from Archbishop Annibale Bugnini: This is quite revealing. The Archbishop could not find the Roman liturgy in Hippolytus. He failed to recognize the ancient liturgy that we’ve seen throughout this series, and so dismissed it as archaic and difficult to understand, to be replaced by more contemporary anaphora as prerequired by his tradition. This precisely demonstrates the Roman Catholic approach: (re)interpret history only through the lens of the church and of personal faith. It is anachronistic. It is eisegesis. In all my research on the Eucharist, never have I seen such a fuss over one source. But it doesn’t end there. Timothy F. Kauffman identified another example: Such is the sorry condition of modern studies of the ancient liturgies. Just as we saw with Harnack’s rejection of Irenæus’ Fragment 37, Harmon and Easton could not evaluate Hippolytus’ ancient Eucharist except through the lens of that later medieval novelty. They rejected it for similar reasons. Unable to extract herself from the medieval corner into which she had painted herself, Professor Harmon painted her students into an even smaller one, instructing them either to interpret the ancient evidence through a medieval lens, or to join her in her ruthless effort to remove Hippolytus’ liturgy from the historical record (Harmon, 2015). Meanwhile, Easton, unable to think through the evidence before him, simply assumed that Hippolytus must have been exaggerating, and dismissed the ancient evidence. Citation: Timothy F. Kauffman, “The Collapse of the Eucharist, Part 2.” What is that about Fragment 37? I’m glad you asked: The objections essentially came down to two issues that were fundamentally problematic to the narrative academia had been constructing on Irenæus for centuries: namely, that the fragment used symbolic language, “αντιτυπον, antitype” (Migne, P.G. vol 7, col 1253) to describe the elements of the Lord’s Supper even after they were consecrated, and the fragment placed the Eucharist offering prior to the Epiclesis: The fragment separates the Eucharistic oblation from the Consecration, whereas Irenæus did not. (von Harnack, A., Die Pfaff’schen Irenäus-Fragmente als fälschungen Pfaffs Nachgewiesen, J. C. Hinrichs’sche Buchhandlung, 1900) 9, 52) These two objections are so easily overturned that it is remarkable they were even raised in the first place. … In short, two of the most significant academic objections to Fragment 37 are based on errors and intentional misrepresentations that are easily dismissed. Therefore, whatever objections have been raised against Pfaff and his discovery of Fragment 37, Irenæus’ liturgy and depiction of the Lord’s Supper in that fragment rather lend proof to its authenticity than to its forgery. The attempts by the scholars to suppress the Fragment are not because the fragment is inconsistent with Irenæus, but rather because it is inconsistent with their creative and illicit attempts to collapse Irenæus’ Eucharist into his Epiclesis. The Fragment itself is entirely consistent with Irenæus’ liturgy and his view of the Eucharist tithe offering as the fulfillment of the Malachi prophecy, an offering that was separate from, and prior to, the Epiclesis. Citation: Timothy F. Kauffman, “The Collapse of the Eucharist, Part 2.” If you are interested in Kauffman’s detailed explanation, you can read more at the link above. You may also want to review Part 6: Irenaeus of Lyons to see how closely his liturgies coincide with that of Hippolytus. Hippolytus described a (1-3) sacrifice of the Eucharist, which included various agricultural products and a spoke customized liturgy full of symbolic significance. He also described a separate (4-5) consecration and celebration of the Lord’s Supper. In doing so, the Roman liturgy is nowhere to be found. As we noted at the outset of this series, there is no evidence of the Roman liturgy—offering Christ’s body as sacrifice to the Father—in the first 300 years of the church. None. It is completely absent. For it to exist requires it to be added in after the fact, and as has been aptly demonstrated throughout this series, it most certainly has been. More than a billion people put their faith a Church that freely engages in and accepts fraudulent interpretations.