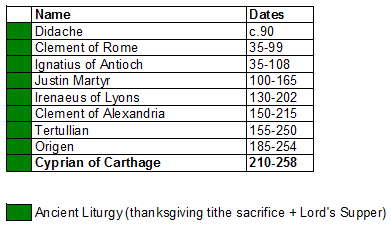

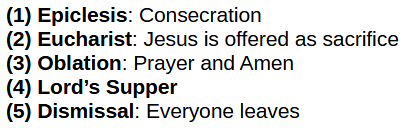

The original liturgy:

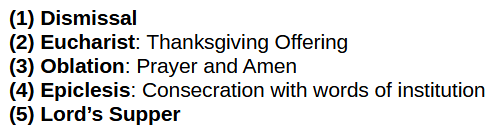

The Roman liturgy:

Cyprian of Carthage

Before we talk about Cyprian, let’s see how the Catholic Encyclopedia sings his praises:

…

St. Cyprian was the first great Latin writer among the Christians, for Tertullian fell into heresy, and his style was harsh and unintelligible. Until the days of Jerome and Augustine, Cyprian’s writings had no rivals in the West. Their praise is sung by Prudentius, who joins with Pacian, Jerome, Augustine, and many others in attesting their extraordinary popularity.

…

Cyprian probably thought that questions of heresy would always be too obvious to need much discussion. It is certain that where internal questions of heresy would always be too obvious to need much discussion. It is certain that where internal discipline was concerned he considered that Rome should not interfere, and that uniformity was not desirable — a most unpractical notion. We have always to remember that his experience as a Christian was of short duration, that he became a bishop soon after he was converted, and that he had no Christian writings besides Holy Scripture to study besides those of Tertullian. He evidently knew no Greek, and probably was not acquainted with the translation of Irenaeus.

Citation: John Chapman, “St. Cyprian of Carthage.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 4. (1908)

It is certainly notable here how the Catholic Encyclopedia is trying to distance Tertullian from his pupil Cyprian. The Catholic Encyclopedia calls Tertullian’s writings “harsh and unintelligible.” The Encyclopedia seems to be setting it up so that Cyprian’s viewpoints perceived to be associated with Tertullian can be rejected out-of-hand as the errors of inexperience and lack of learning. For as we saw in many citations in Part 9: Tertullian, Tertullian had joined the other patristic writers in a non-Roman Eucharistic liturgy.

Did Cyprian agree with his master? Let’s find out.

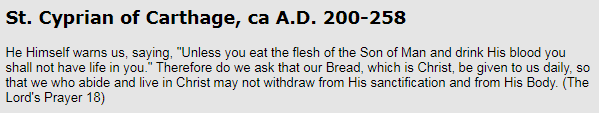

With Cyprian having authored 81 letters, we would expect much more than a solitary quote. Indeed, as we’ll see below, this is precisely what we have. But, since FishEaters has started with “The Lord’s Prayer”, let’s start there too. We’ll come to the rest later.

Here, just as in Part 10: Origen of Alexandria, Cyprian too speaks of the (4-5) celebration of the Lord’s Supper, but the (1-3) sacrifice of thanksgiving is conspicuously absent. On numerous occasions now, we have read how the sacrifice and the celebration are separate acts. And so, by omission, the Roman liturgy is not found in Cyprian. But we do not have to stop there, for later in the same work Cyprian does speak about the sacrifice, and so too there is the celebration absent:

…

He promises that He will be at hand, and says that He will hear and protect those who, loosening the knots of unrighteousness from their heart, and giving alms among the members of God’s household according to His commands, even in hearing what God commands to be done, do themselves also deserve to be heard by God. The blessed Apostle Paul, when aided in the necessity of affliction by his brethren, said that good works which are performed are sacrifices to God.

For when one has pity on the poor, he lends to God; and he who gives to the least gives to God — sacrifices spiritually to God an odour of a sweet smell.

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Treatise IV: The Lord’s Prayer.” §33″

Now see Cyprian echo the understanding of those who see Malachi’s prophecy—as described in Part 8: Interlude—as the thanksgiving sacrifice of prayer, praise, service, and tithes: Jesus, John, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Origen. Cyprian only alludes to it here, but he makes it explicit elsewhere:

Also in the forty-ninth Psalm:

In the same Psalm, moreover:

In the fourth Psalm too:

Likewise in Malachi:

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Treatise 12, Book I.” ¶16

With Malachi and the Psalms in mind, Cyprian describes the sacrifice of thanksgiving and praise that Christians make, and it is not Christ’s body and blood. In these he echoes Part 2: The Didache.

In “The Lord’s Prayer”, Cyprian also mentions the Dismissal, which in the Roman Mass (Mass means “dismissal”) occurs at the very end when the service concludes and everyone leaves.

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Treatise IV: The Lord’s Prayer.” §23″

It is (1) the Dismissal. One cannot participate in the lesser sacrifice—the Eucharist—before participating in the greater sacrifice—reconciliation. Cyprian also references the Dismissal in one of his stories:

And another woman, when she tried with unworthy hands to open her box, in which was the holy (body) of the Lord, was deterred by fire rising from it from daring to touch it. And when one, who himself was defiled, dared with the rest to receive secretly a part of the sacrifice celebrated by the priest; he could not eat nor handle the holy of the Lord, but found in his hands when opened that he had a cinder. Thus by the experience of one it was shown that the Lord withdraws when He is denied; nor does that which is received benefit the undeserving for salvation, since saving grace is changed by the departure of the sanctity into a cinder.

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Treatise III: On the Lapsed.” §26″

In the first story, Cyprian makes a reference to the standard practice of (1) dismissing the unbeliever, catechumen, and backslider prior to the (2-3) sacrifice of the Eucharist and the (4-5) celebration of the Lord’s Supper. In the second story, Cyprian notes that a woman was deterred from offering her eucharist, that is, her tithe that she had brought in a box. She was unworthy, and so (1) could not make her offering. Cyprian’s point is that the unworthy should be dismissed prior to making their offering, and that to fail in the dismissal is a grave offence.

Cyprian’s eucharist was a tithe that each person brought to the gathering of believers where the Lord’s Supper was to be celebrated:

Greatly blessed and glorious woman, who even before the day of judgment hast merited to be praised by the voice of the Judge! Let the rich be ashamed of their barrenness and unbelief. The widow, the widow needy in means, is found rich in works. And although everything that is given is conferred upon widows and orphans, she gives, whom it behooved to receive, that we may know thence what punishment, awaits the barren rich man, when by this very instance even the poor ought to labour in good works. And in order that we may understand that their labours are given to God, and that whoever performs them deserves well of the Lord, Christ calls this the offerings of God, and intimates that the widow has cast in two farthings into the offerings of God, that it may be more abundantly evident that he who has pity on the poor lends to God.

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Treatise VIII: On Works and Alms.” §23″

Notice how Cyprian says “…come to the Lord’s Supper Without a sacrifice?” Cyprian talks about how the rich did not bring their alms to offer to the congregation. They came only to participate in the Lord’s Supper, which is itself supplied from the gifts—the eucharist—brought by those who were poor. But in the Roman liturgy, it is not possible to come to the Lord’s Supper either with or without a sacrifice, for in the Roman liturgy the sacrifice is Christ’s body to which the laity bring nothing but themselves. But in Cyprian’s day, (1-3) the eucharist was the tithe offering, a sacrifice that preceded the (4-5) celebration of the Lord’s Supper.

With this in mind, let’s go back to the original quotation and see how this applies there:

And therefore we ask that our bread — that is, Christ — may be given to us daily, that we who abide and live in Christ may not depart from His sanctification and body.

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Treatise IV: The Lord’s Prayer.” §18″

While elsewhere in our examination, Cyprian used “Eucharist” to mean (2-3) the sacrifice of the tithe offering, but here Cyprian used the term “Eucharist” to mean (4) consecrated bread and wine. What the Roman Catholic wants you to believe is that Cyprian saw no difference between the offered and unconsecrated Eucharist and the consecrated Eucharist of the Lord’s Supper, but as we’ve seen, he keeps these concepts separate. It was the offering (or sacrifice) that made the Eucharist holy, not the consecration by the words of initiation. Whether the Eucharist went to the poor, was used in the baptismal rites for the anointing by oil (see below), or was set aside to be consecrated for the Lord’s Supper, it was all the holy Eucharist.

Though FishEaters only cited “The Lord’s Prayer,” she could have also cited another example:

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Epistle 10.” §1″

Notice the strict ordering of Cyprian’s liturgy. He says that these lapsed (1) did not confess their sins (i.e. participated when the presbyters should have dismissed them), then the presbyters (2-3) offered the sacrifice of the Eucharist on their behalf, and then they gave the lapsed the (4-5) consecrated body of the Lord. Though Cyprian uses the term “Eucharist” of the consecrated bread, he nonetheless maintains the order of the liturgy. The whole process was profane, but especially taking the consecrated Eucharist.

Now let’s explain that passing reference above to the anointing with oil at baptism.

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Epistle 69. §2″

The newly baptized were anointed with oil from the Eucharist—the tithe offering of firstfruits, which included more than bread and wine. We’ve already seen the reference to oil in the Eucharist—tithe offering—in the Part 2: The Didache and we’ll see it again next in Part 12: Hippolytus of Rome.

The ceremony of baptism was no more a part of the Eucharist—the tithe—than the Lord’s Supper was. What baptism and the Lord’s Supper have in common is that both of these ceremonies took their elements from the Eucharist. The bread and wine are elements of the Lord’s Supper, and the oil is an element of the baptismal anointing. Neither the Lord’s Supper nor baptism are a sacrifice, for there is only one sacrifice remaining for Christians: the sacrifice of thanksgiving.

Now let’s look at some of Cyprian’s other epistles to add more confirmation to what we’ve already seen:

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Epistle 59.” ¶4

This is another example of how good works of service and financial support (i.e. tithes of money) are (2) presented to God with a (3) sacrifice and prayer.

With this caveat in mind, here are a couple relevant citations:

Can water make garments red? Or is it water in the wine-press which is trodden by the feet, or pressed out by the press? Assuredly, therefore, mention is made of wine, that the Lord’s blood may be understood, and that which was afterwards manifested in the cup of the Lord might be foretold by the prophets who announced it. The treading also, and pressure of the wine-press, is repeatedly dwelt on; because just as the drinking of wine cannot be attained to unless the bunch of grapes be first trodden and pressed, so neither could we drink the blood of Christ unless Christ had first been trampled upon and pressed, and had first drunk the cup of which He should also give believers to drink.

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Epistle 62.” ¶7

For the Roman liturgy to work, Jesus had to have offered his literal body and blood at the Last Supper with the disciples. But here Cyprian tosses that view aside as logically impossible. Jesus could not have given his literal body and blood as sacrifice because he had not yet died (“been trampled upon” by his crucifixion and “drunk the cup” of suffering that Christians share in). According to Cyprian, when Jesus said “this is my body” and “this is my blood” he meant it figuratively.

Let’s pause to consider this further. Cyprian had only Tertullian and the Word of God to guide him. With limited to no influence from doctrinal factions, external tradition, and outside sources of authority, he was thus obligated to conclude from scripture alone that Jesus must have been speaking metaphorically when he spoke the words of institution. It is no wonder that Epistle 62 was later mistranslated in an attempt to insert the Roman liturgy.

As often, therefore, as we offer the cup in commemoration of the Lord and of His passion, let us do what it is known the Lord did.

Citation: Cyprian of Carthage, “Epistle 62.” ¶17

Cyprian does two things here. First, he claims that we sacrifice Christ’s passion, not his body. This is clearly figurative language. Second, he claims that we make this sacrificial offering in the Lord’s Supper in the form of a commemoration. The Roman liturgy is, once again, not present.