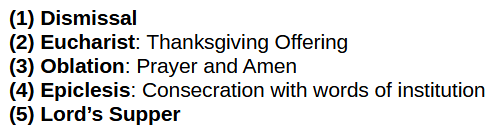

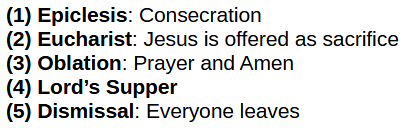

The original liturgy:

The Roman liturgy:

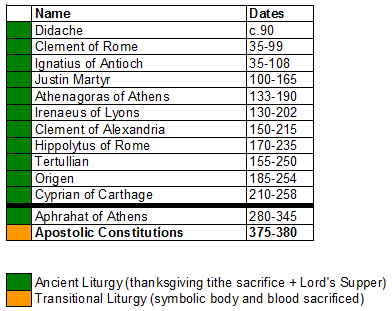

Apostolic Constitutions (c.375-380)

In Part 15: Athenagoras of Athens, we began a discussion on the Apostolic Constitutions, written two centuries after Athenagoras. There we discovered that the unbloody sacrifice is the eucharist of a pure heart and unreprovable mind. This is precisely what we’ve seen in our series so far: the sacrifice that the church offered was a (2-3) thanksgiving—or Eucharist—of tithes, gifts, service and good works, gratitude, prayers, praise, hymns, and a pure heart.

Here is a quick review of the references we examined:

You, therefore, O bishops, are to your people priests and Levites, ministering to the holy tabernacle, the holy Catholic Church; who stand at the altar of the Lord your God, and offer to Him reasonable and unbloody sacrifices through Jesus the great High Priest.

…

Those which were then the sacrifices now are prayers, and intercessions, and thanksgivings. Those which were then first-fruits, and tithes, and offerings, and gifts, now are oblations, which are presented by holy bishops to the Lord God, through Jesus Christ, who has died for them.

Citation: “Apostolic Constitutions, Book II.” §4

Instead of a bloody sacrifice, He has appointed that reasonable and unbloody mystical one of His body and blood, which is performed to represent the death of the Lord by symbols.

Citation: “Apostolic Constitutions, Book VI.” §4.23

…according to Your command; to loose every bond, according to the power which You gave the apostles; that he may please You in meekness and a pure heart, with a steadfast, unblameable, and unreprovable mind; to offer to You a pure and unbloody sacrifice, which by Your Christ You have appointed as the mystery of the new covenant…

Citation: “Apostolic Constitutions, Book VIII.” §2.5

…But after His ascension we offered, according to His constitution, the pure and unbloody sacrifice…

Citation: “Apostolic Constitutions, Book VIII.” §5.46

But while the Apostolic Constitutions describes the ancient Eucharist as a truly unbloody sacrifice, it is also one of the very first documents to display liturgical innovation of the Eucharist and Lord’s Supper, displaying hints of what would become the established medieval Roman liturgy of the 6th or 7th century. If you pay closer attention to the quote above, you’ll see this line:

This is so subtle that if you blink, you’d miss it. Throughout this series, we’ve seen how firstfruits, tithes, offerings, and gifts were all offered with an oblation. The oblation of the Eucharist—the thanksgiving prayer—was always the sacrifice proper, not the gifts themselves which were figures of the sacrifice. But this seems to suggest the possibility of an oblation of the Eucharist without any tithe at all. It is ambiguous and so opens the door for other interpretations. Certainly it doesn’t directly contradict anything we’ve seen in the series so far, but we need to see what else Apostolic Constitutions has to say.

…

Let us still further beseech God through His Christ, and let us beseech Him on account of the gift which is offered to the Lord God, that the good God will accept it, through the mediation of His Christ, upon His heavenly altar, for a sweet-smelling savour.

Citation: “Apostolic Constitutions, Book VIII.” §12-13

Can you see the change? To this point in our series, we have not seen anything like it (outside of fraudulent translations), so study it carefully. It is extremely important. Do you see it?

The consecrated bread and wine are now being brought forward into the Eucharist sacrifice, combined into one liturgical action.

As we showed above, the Apostolic Constitutions still considers the bread and wine to be symbols, so not literal flesh and blood, but the consecrated elements are now offered to God on God’s altar (i.e. they are sacrificed). This “small” change still does not match the Roman liturgy, but in terms of liturgical development it is a truly massive shift. And, as we’ll see in the next interlude, it coincides precisely with the rise of Roman Catholicism in the late 4th century.

We have one more reference to make:

For it is not lawful to offer anything besides these at the altar, and oil for the holy lamp, and incense in the time of the divine oblation.

But let all other fruits be sent to the house of the bishop, as first-fruits to him and to the presbyters, but not to the altar. Now it is plain that the bishop and presbyters are to divide them to the deacons and to the rest of the clergy.

Citation: “Apostolic Constitutions, Book VIII.” §47.3-5

This partially explains the apparent ambiguity we saw in the other quote:

We now have a unique insight into how the doctrinal development first came to be. The Eucharist was still a tithe offering, as per the ancient liturgy, but its nature had been changed in two critical ways.

First, no longer were all agricultural products accepted as a tithed thanksgiving sacrifice. The sacrifice was now limited only to new grains, ears of wheat, and bunches of grapes. Only those items agriculturally related to the production of bread and wine were permitted to be (2-3) sacrificed in the oblation of the Eucharist at the altar. In general, there was now a reduced emphasis on the gifts themselves.

Second, those other items that used to be offered in the tithe for the previous 300 years were still given, but were now delivered straight to the storehouse of the bishop, for later use by the bishop, presbyters, deacons, and the other clergy, not for the poor. They were still given, of course, but were no longer part of the Eucharist and oblation.

So we see hints in Apostolic Constitutions how the Eucharist was corrupted into the Roman liturgy. The combination of the Eucharist with the Lord’s Supper—the unconsecrated tithe with the consecrated elements—was driven by an expansion of the clergy and a reallocation of the tithe as a sacrifice for the poor and needy into a payment for clergy services. We can also see how, by restricting the contents of the tithe, it would only a few short steps before even raw grains, wheat, and grapes would be simply replaced by these three things: financial support for the clergy, bread for the Lord’s Supper, and wine for the Lord’s supper. Eventually, only financial support for the church as its own independent entity would remain.

Nothing would remain of the original Eucharist. The sacrifice of tithes, gifts, service, good works, gratitude, prayers, praise, hymns, and a pure heart and mind? Replaced by financial gifts to fill the coffers of the churches and the clergy that ran them. Greed was the root of this new evil.

You can see precisely how this happened. Given a brand new universal authority centered in Rome, it would just be a matter of time before every church was forced to implement these new policies. As soon as these changes were implemented, it would be only a few decades before people simply forgot about the old way of doing things.

The Apostolic Constitutions purports to be written by the Twelve Apostles. For a long time it was casually mistaken as authentic, understood to have been passed down by Clement of Rome. The best the Catholic Encyclopedia can say is that it wasn’t completely accepted without some doubt eventually:

Citation: John Bertram Peterson, “Apostolic Constitutions.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 1 (1907)

Nonetheless, the Catholic Encyclopedia is forced to admit that, in fact, the document was both highly regarded and highly influential on matters of ecclesiastical legislation.[1] No kidding! I figured that out solely on the basis of my knowledge of the history of the first 300 years of the church compared with the mere fact of the Roman liturgy of today. Who can read Apostolic Constitutions and not see in it the rise of Roman Catholicism and the corresponding growth and abuse of the power, wealth, and influence of the Catholic clergy and its effect on church law and the liturgy?

Perhaps most damning is that it was regarded as canonical into the 5th century, but was only rejected as non-canonical in the 6th (Decretum Gelasianum; between c.519 and c.553) and 7th centuries (Quinisext Council; 692). Thus was the document instrumental in changing away from the ancient liturgy, only to be rejected as heresy after it failed to comport with additional doctrinal innovation. What does that sound like?

The biggest problem with Apostolic Constitutions is that it wasn’t heretical enough for Roman Catholicism. But, it served its purpose, nonetheless.

We agree with the Catholic Encyclopedia that the writings…

…for the Apostolic Constitutions remain as compelling evidence of (A) the development of the Eucharistic liturgy away from the ancient liturgy; and (B) that the Roman liturgy is itself built upon its heresy.

But before we conclude, I wanted to highlight one more thing:

As we discussed in Part 13: Aphrahat the Persian Sage, this is factually incorrect and betrays a 4th-century ignorance of 1st century wine production and meal preparation methods. Given how influential the Apostolic Constitutions were, we are not surprised to see that this error exists here.

Footnotes

[1] Similarly, forgeries Gnostic Protoevangelium of James, Donation of Constantine, and False Decretals were used in the development of church law. Their rejection as forgeries did not involve rolling back the changes that the forgeries helped to enact.