It is well understood that the victors write the history books. For better or worse, the winners tend to portray themselves in a positive light and their enemies in a negative light. It is not unusual for this portrayal to be a complete inversion of reality. You can see hints of that in the mini review “Bearing False Witness.”

In the 4th and 5th centuries, Leo I—along with his predecessors and successors in Rome—came out on top. And, yet, despite being able to write their own history books, their own account manages to record their negative deeds. One can only imagine that what Leo actually did was much worse than what is recorded and what Leo’s enemies supposedly did and believed is overstated or outright false.

So too, I suspect, is much of the history of Roman Catholicism.

During my series on “Papal Primacy in the First Councils,” I ran across an article in the Catholic Encyclopedia. It is a fantastic example of many of the topics we’ve been discussing lately, including the creation and development of Papal Primacy out of nothing, the fraudulent use of the Nicaean Canons by Leo and Rome, and the historical myths that people believe.

The greatly disorganized ecclesiastical condition of certain countries, resulting from national migrations, demanded closer bonds between their episcopate and Rome for the better promotion of ecclesiastical life. Leo, with this object in view, determined to make use of the papal vicariate of the bishops of Arles for the province of Gaul for the creation of a centre for the Gallican episcopate in immediate union with Rome.

In the beginning his efforts were greatly hampered by his conflict with St. Hilary, then Bishop of Arles. Even earlier, conflicts had arisen relative to the vicariate of the bishops of Arles and its privileges. Hilary made excessive use of his authority over other ecclesiastical provinces, and claimed that all bishops should be consecrated by him, instead of by their own metropolitan.

When, for example, the complaint was raised that Bishop Celidonius of Besançon had been consecrated in violation of the canons—the grounds alleged being that he had, as a layman, married a widow, and, as a public officer, had given his consent to a death sentence—Hilary deposed him, and consecrated Importunus as his successor. Celidonius thereupon appealed to the pope and set out in person for Rome. About the same time Hilary, as if the see concerned had been vacant, consecrated another bishop to take the place of a certain Bishop Projectus, who was ill. Projectus recovered, however, and he too laid a complaint at Rome about the action of the Bishop of Arles.

Hilary then went himself to Rome to justify his proceedings. The pope assembled a Roman synod (about 445) and, when the complaints brought against Celidonius could not be verified, reinstated the latter in his see. Projectus also received his bishopric again. Hilary returned to Arles before the synod was over; the pope deprived him of jurisdiction over the other Gallic provinces and of metropolitan rights over the province of Vienne, only allowing him to retain his Diocese of Arles.

Citation: “Pope St. Leo I (the Great).” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910.

This was written in 1910, a hundred and fifteen years ago. No doubt virtually no modern reader would know much (if anything) about about the history of Gaul, the Gallican episcopate, Arles, Besançon, and the province of Vienne. Even men and women who attended Catholic schools probably do not know about the Council of Turin, which doesn’t even have a Wikipedia page or an entry in the Catholic Encyclopedia.

Now compare this to a modern secular encyclopedia:

Hilary succeeded his kinsman Honoratus as bishop of Arles in 429. Following the example of Augustine of Hippo, he is said to have organized his cathedral clergy into a “congregation,” devoting a great part of their time to social exercises of asceticism. He held the rank of metropolitan bishop of Vienne and Narbonne, and attempted to exercise the sort of primacy over the church of south Gaul, which seemed implied in the vicariate granted to his predecessor Patroclus of Arles (417).

Hilary deposed the bishop of Besançon, Chelidonus, for ignoring this primacy, and for claiming a metropolitan dignity for Besançon. An appeal was made to Rome, and Pope Leo I used it, in 444, to extinguish the Gallican vicariate headed by Hilary, thus depriving him of his rights to consecrate bishops, call synods, or oversee the church in the province.

The pope also secured the edict of Valentinian III, so important in the history of the Gallican church, which freed the Church of Vienne from all dependence on that of Arles. These papal claims were made imperial law, and violation of them were subject to legal penalties. Léon Clugnet suggests that the dispute arose from the fact that the respective rights of the Court of Rome and of the metropolitan were not sufficiently clearly established at that time, and that the right of appeal to the pope was not explicitly enough recognized.

In case the reference to Patroculus of Arles in 417 AD is unclear, that is when “Pope” Zosimus issued a letter to Patroclus, Bishop of Arles, conferring on him the rights of a Metropolitan over the Gallic provinces of Viennensis, Narbonensis I, and Narbonensis II. Keep that in mind, as we’ll come back to it. We’ll also revisit Wikipedia’s version of history.

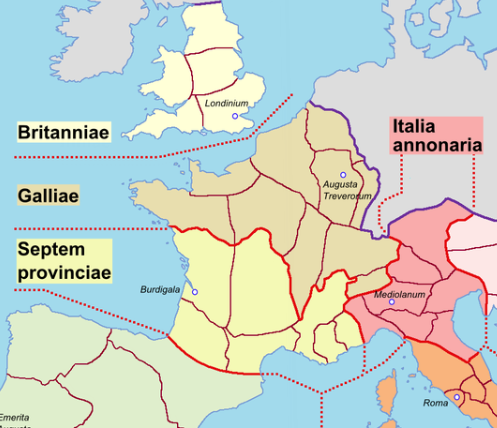

All of the places mentioned by the Catholic Encyclopedia are found in the provinces of Galliae and Septum Provinciae, also known as the Diocese of Gaul and the Diocese of Viennensis. According to Wikipedia, here is what the division of the Western Empire looked like in c.300AD:

And here is what Wikipedia claims the division of the Western empire looked like in c.400AD:

As you can see, the diocesan and provincial divisions are the same. But there is more to the story, which I first described in footnote 1 of “Eschatology: Ten and Three Horns.”

The notitia dignitatum refers to both Viennensis, Gaul, and Septem Provinciæ as being essentially coterminous…

…and states that the diocese of Septem Provinciae included…

…which directly contradicts Wikipedia’s assertion that diocese contained only…

…even as Wikipedia’s list of provinces in the diocese of Gaul included…

Note the regional overlap in the official record. The Laterculus Veronensis described Gaul and Viennensis as separate dioceses in the early 4th century in 314AD . The Notitia Dignitatum…

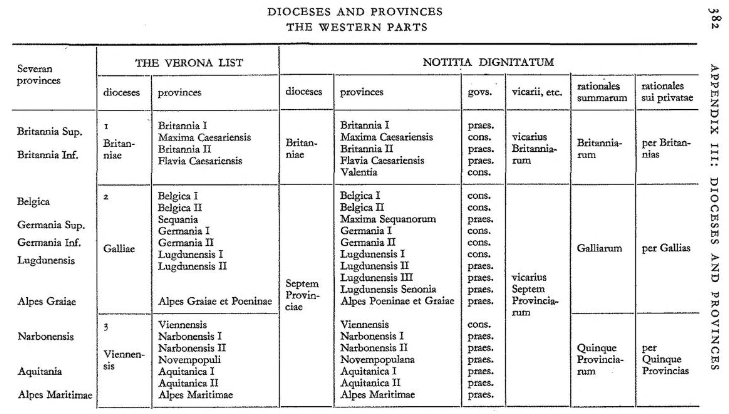

A.H.M. Jones summarizes the issue in a table of dioceses in The Later Roman Empire 284-602, Vol 3 on page 382, where he utilizes the Verona List (314AD), Festus’s Breviarium, Ammianus’s geographical excursuses, the conciliar lists of the fourth century, the Notitia Dignitatum, the Notitia Galliarum, Polmius Silvius, the conciliar lists of the Council of Chalcedon and Epistles of Leo, the Synecdemus of Hierocles, the schedule to Just. Nov. VIII, Georgius Crprius, and Justinian Code.

The chart shows that Gaul and Viennensis were separate in 314AD when there were 12 dioceses matching the initial 12 Diocletian divisions in the third century, but were later combined into Septem Provinciae by the 5th century when there were 13 dioceses (reflecting the split of Oriens into Oriens and Egypt). Some 5th century historians do not combine Septem Provinciae and thus show 14 dioceses.

In 400AD, Arles became the civil seat of the Praetorian Prefect of Gaul. After a series of barbarian invasions and instability within Gaul at the beginning of the 5th century, the southern provinces within the Diocese of Viennensis continued to gain power and importance. In 417, Zosimus wrote his letter to Patroclus, Bishop of Arles, granting him explicit ecclesiastical jurisdiction over the provinces of Viennesis, Narbonensis I, and Narbonensis II in Southern Gaul. But that was not all. The Catholic Encyclopedia explains:

In addition [Patroclus] was made a kind of papal vicar for the whole of Gaul, no Gallic ecclesiastic being permitted to journey to Rome without bringing with him a certificate of identity from Patroclus.

In the year 400 Arles had been substituted for Trier as the residence of the chief government official of the civil Diocese of Gaul, the “Prefectus Praetorio Galliarum”. Patroclus, who enjoyed the support of the commander Constantine, used this opportunity to procure for himself the position of supremacy above mentioned, by winning over Zosimus to his ideas. The bishops of Vienne, Narbonne, and Marseilles regarded this elevation of the See of Arles as an infringement of their rights, and raised objections which occasioned several letters from Zosimus. The dispute, however, was not settled until the pontificate of Pope Leo I.

“Pope St. Zosimus.” The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912.

The next year, in 418, the Council of the Seven Provinces (concilium septem provinciarum) was formed in Arles to govern over the entirely of Gaul, both the seven provinces in the south and the remaining provinces in the north (such as they were).

Thus was the civil and ecclesiastical Diocese of Gaul (under the Metropolitan in Trier) and the civil and ecclesiastical Diocese of Viennensis (under the Metropolitan in Vienne) reorganized into the Septem Provinciae (under the Metropolitan in Arles). This reorganization was both civil and ecclesiastical.

The core of the disagreement is simple. For almost three decades from 417 through 444, Arles had been granted by the Bishop of Rome jurisdiction over the whole of Gaul. Quite simply put, if Zosimus was the Pope and had the rightful authority over the church, then Arles was the rightful seat of the Metropolitan of Septem Provinciae. Then Leo, citing his authority as Pope, simply undid what his predecessor had done.

Obviously this creates quite the contradiction for proponents of papal authority, but there is something much more interesting at play here. Both Zosimus and Leo cited the Canons of Nicaea to justify completely opposite decisions.

Something had changed in the two decades between Zosimus and Leo. Zosimus had been focused on establishing Rome’s prerogative to hear appeals in extraordinary cases. His claims did not constitute a comprehensive assertion of universal authority, but were rooted on the appeals process described by the Council of Sardica (and misattributed to Nicaea). By contrast, Leo’s much more ambitious vision of primacy was expansive: universal jurisdiction over all ecclesiastical matters. His claims—echoing Damasus—were rooted in a Petrine foundation.

You may recall from our previous series that Zosimus had conflated the Canons of the Council of Sardica (343) with the Canons of the Council of Nicaea (325). But Leo, in his letter to the Gallican bishops, also implicitly appealed to the Canons of Nicaea as supporting the prerogatives of the Roman “Apostolic See:”

And so we would have you recollect, brethren, as we do, that the Apostolic See, such is the reverence in which it is held, has times out of number been referred to and consulted by the priests of your province as well as others, and in the various matters of appeal, as the old usage demanded, it has reversed or confirmed decisions: and in this way “the unity of the spirit in the bond of peace” (Ephesians 4:3) has been kept, and by the interchange of letters, our honourable proceedings have promoted a lasting affection: “for seeking not our own but the things of Christ” (Philippians 2:21), we have been careful not to do despite to the dignity which God has given both to the churches and their priests. But this path which with our fathers has been always so well kept to and wisely maintained, Hilary has quitted, and is likely to disturb the position and agreement of the priests by his novel arrogance: desiring to subject you to his power in such a way as not to allow himself to be subject to the blessed Apostle Peter, claiming for himself the ordinations of all the churches throughout the provinces of Gaul, and transferring to himself the dignity which is due to metropolitan priests;

Let each province be content with its own councils, and let not Hilary dare to summon synodal meetings besides, and by his interference disturb the judgments of the Lord’s priests. And let him know that he is not only deposed from another’s rights, but also deprived of his power over the province of Vienne which he had wrongfully assumed. For it is but fair, brethren, that the ordinances of antiquity should be restored, seeing that he who claimed for himself the ordinations of a province for which he was not responsible, has been shown in a similar way in the present case also to have acted so that, as he has on more than one occasion brought on himself sentence of condemnation by his rash and insolent words, he may now be kept by our command in accordance with the clemency of the Apostolic See to the priesthood of his own city alone.

However, those ordinances of the fathers pertaining to jurisdictions in appeals and jurisdiction actually came from the non-ecumenical Council of Sardica. Thus, the basis for Leo’s argument was completely invalid, indeed fraudulent.

Now, let’s look at the logic of Zosimus’ and Leo’s actions in light of the actual Canons of Nicaea and the historical precedents, to see if either “Pope” made a decision that conformed to the “ordinances of antiquity.”

Let’s consider the historical arrangement prior to Zosimus. The Metropolitan of Viennensis in Vienne had rule over the whole of the seven southern provinces of Gaul (collectively the Diocese of Viennensis). The Metropolitan of Gaul in Trier had rule over the whole of the northern provinces of Gaul (collectively called the Diocese of Gaul).

Zosimus clearly opposed this arrangement. But did he have a canonically established right to enforce a transfer the Metropolitan from the Bishop of Vienne to the Bishop of Arles? According to Nicaea, the Metropolitan right should have remained with Vienne. Zosimus chose to side with the civil Roman practice since the time of Constantine, rather than the ecclesiastical practice since the time of Nicaea. But, by Canon 3 of the Council of Constantinople—which Rome rejected—you could make the case that Arles should have become “New Vienne” as the replacement for “Old Vienne.” So, either way, Zosimus was wrong.

But, this does not mean Leo was correct either.

Leo claimed that Zosimus’ preferred arrangement which had held in Arles for a generation—three to five decades—had only been temporary:

But there is no evidence that this was the case. Zosimus made him a papal vicar and granted him Metropolitan jurisdiction, thus granting him the power over ordinations. There is no sense at all that this was intended to be temporary. Leo’s claim appears to be pure historical revisionism. That is why historical accounts—such as the one by Wikipedia above—discount Leo’s reinterpretation of events.

The Catholic Encyclopedia, Wikipedia, and Leo himself all missed something really important: the Council of Turin.

…

The council took into consideration the differences, between the archbishops of Aries and Vienne, who both, pretended to the primacy of Viennese Gaul. The decision was that he of the two who could prove his city to be the metropolis of the province as to civil matters, should be considered as the lawful metropolitan, and in the meantime they were exhorted to live in peace.

It was the Council of Turin in 398 (or 401)—not Zosimus—that first instituted the idea that the ecclesiastical Metropolitan should follow the civil Metropolitan. This, more than anything else, is why Arles becoming the official seat of civil government of Gaul in 400AD meant that Arles took the ecclesiastical jurisdiction from Vienne.

Notice that the council took place in Turin under the domain of Milan—the rightful Metropolis of Italy—and not in Rome. When the bishops in the Diocese of Viennensis could not come to terms, they appealed to the Nicaean Metropolitan of Italy. And it wasn’t Rome.

In any case, when Zosimus wrote his letter in 417, Arles had already been the “rightful” Metropolis for 17 years. The only difference is that instead of asking Milan (through the Council in Turin), they appealed to Rome this time, allowing a different Bishop to weigh in. The answer, however, was the same, and it remained the same—despite the official protest—for three more decades through the reigns of Zosimus, Boniface, Celestine, Sixtus, and to Leo himself.

But, frankly, even Leo didn’t really believe the original arraignment had been temporary because he did not restore the historical arrangement that had supposedly been temporarily altered. He did not restore the Bishop of Vienne to his previous Metropolitan status, rather, he ruled that all the bishops would now rule over their own provinces and not have any overlapping jurisdictions. In doing so, he eliminated the historical arrangement and placed himself—and only himself—as the chief Metropolitan over them. The Catholic Encyclopedia leaves out any mention of what happened to the Bishop of Vienne, a critically important contextual oversight that undermines the entire historical narrative.

Leo’s actions were not attempts to restore the previous arrangement, but to affirm that all bishops rule by the say-so of the Bishop of Rome. It was a blatant—and largely successful—attempt to permanently remove a Metropolitan (or two) and transfer the power to Rome. It was a coup. It most certainly was not based on the ancient ordinances of the Council of Nicaea, which he consistently lied about throughout his career in the church, both before and after this controversy.

But, there is one more thing to note. In 445, Leo successfully pushed for and obtained an imperial edict from Emperor Valentinian III declaring the primacy of the Roman Church:

These decisions were disclosed by Leo in a letter to the bishops of the Province of Vienne (ep. x). At the same time he sent them an edict of Valentinian III of 8 July, 445, in which the pope’s measures in regard to St. Hilary were supported, and the primacy of the Bishop of Rome over the whole Church solemnly recognized “Epist. Leonis,” ed. Ballerini, I, 642).

This made papal jurisdiction over the Western Church a matter of imperial law, reinforcing Leo’s position against Hilary. Just as Leo did with the Council of Chalcedon, he used the civil power to unilaterally force through his own decisions on theological matters—at the point of the sword—without establishing consensus among the bishops of the church.

Thus the account given by Wikipedia has proven to be mostly correct while the account given by the Catholic Encyclopedia is biased almost to the point of myth and deception. With that in mind, I want to highlight one more quote:

The pope confirmed the decrees of the Council [of Chalcedon] after eliminating the canon [28], which elevated the Patriarchate of Constantinople, while diminishing the rights of the ancient Oriental patriarchs.

The Council of Chalcedon took place in 451, six years after Leo had successfully wrested full control away from two Western patriarchs by citing the Council of Nicaea (while, of course, being in defiance of it). But, when the Eastern bishops did the exact same thing on behalf of the Bishop of Constantinople, suddenly Rome declared such things to be null and void and an usurpation and violation of the ancient canons. Then, when Leo couldn’t have his way, he appealed not to the church, but to the Emperor.

The Catholic Encyclopedia, of course, makes no mention of this as if the Eastern church had merely granted Rome the whole of the church, when Leo had only recently stolen power in the West and the Emperor had only recently assigned the West to the Bishop of Rome by imperial decree. But, when you write the history books you can spin it however you like.

Out of curiosity, why are you writing these posts? Why is RC church history interesting to you?

Lucas,

You express curiosity—a good trait indeed—but do not explain why you are curious. Are you a Roman Catholic? Do you have a problem with validating theology to see if it is consistent with history? Don’t you find these analyses interesting and relevant?

First, it is not a new phenomenon. I’ve been “doing apologetics” online since the 90s. It is impossible not to have attracted the attention of Roman Catholics, which naturally leads to more discussion and content.

Roman Catholics make a ton of theologically rich historical claims, more than any other denomination. And they assume that their claims are exclusively true, often explicitly tying their historical beliefs directly into their core theological beliefs. If I want to address the theological claims, I have to write about the historical claims.

Second, some of the most extensive online discussions that I’ve ever had were with Roman Catholics. Examples include my back-and-forth relationship with Roman Catholic Earl at Boxer’s blog in the 2010s (and mutual following on Twitter since), my discussion in 2017 with Tyler, a months long discussion in 2020 with Phil, Nick, and Betty, a week long discussion in 2022 with Kentucky Gent, and a months long discussion in 2024 with Betty. Along with the writings of Roman Catholic John C. Wright (who I’ve read for many years), these inspired many later writings.

Third, I write about these topics because I’m not susceptible to the Heckler’s Veto. Most interactions with Roman Catholics are positive, civil, and informative (including recent interactions). As noted in my response to “not that Jack,” the common factor on the barren, uninviting, soul sucking nature of the conflict that arises from my writing about these topics “comes from a certain subset of the internet” that I don’t experience in meatspace or elsewhere online.

Fourth, this is an ideas blog and I often focus on logical consistency of belief. This is why I write against atheism, leftism/feminism, mysticism, Roman Catholicism, and [would also be] Mormonism [if I knew any Mormons]. I perceive these as among the least logical, most irrational belief systems, so I gravitate towards them. Most of the topics I write about are “low hanging fruit:” especially egregious instances of error (although the people who believe the ideas I write about don’t agree, obviously).

Fifth, I’m an ethnic Anabaptist. My family’s ancestors personally knew (or were related to) a number of key figures in Anabaptist history. A great many of my ancestors fled religious persecution in the early 1700s. With how common the Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant versions of history are, who is telling an Anabaptist version of history? While my expressed ideas are not logically dependent on me being Anabaptist, it is certainly a personal motivation.

Sixth, it’s about truth. I wouldn’t say that people are lying about the historical narratives—deceived is the better word—but, people are inadvertently passing off mythical stories about the first three or four centuries of church history as if they were truth. Those who are spreading falsehoods (including myself, where applicable) or falling for them should be informed of their error so they can either repent of their error or explicitly reject the truth. It’s about forcing a choice to be made. Pushing for an exercise of this level of agency is in keeping with the overall masculine themes of this blog, even if people ultimately do not agree with me.

As far as my motivation goes, I want—quite strongly—for Roman Catholics to throw off the chains of deception that are holding them captive. The vast majority don’t even have the slightest idea.

Seventh, eschatology. The only rational alternative to writing on these topics, IMO, is to remove the book of Revelation from the biblical canon. I’d rather write all these posts than alter the canon of scripture.

Relatedly, these topics used to be better known among Protestants and Catholics, but hardly anyone discusses them anymore. When I bring them up, people wonder why. But, for example, the idea that Papal Rome is the Whore of Babylon in Revelation precedes the Reformation. There was an entire Counter-Reformation that occurred in direct response to what was once the commonly held view. If this were the 1600s, nobody would have wondered why I would write about these topics.

But, most importantly…

Eighth, the computer age has revolutionized theological historical analysis. It is trivial for almost anyone to fact-check long-standing beliefs against historical claims. The real question is not why I would write about these topics, but why more people are not joining me or (at least) reading those who do.

Ninth, I’m slowly migrating away from the Dalrockian Manosphere and changing the focus of this blog. I project that by the end of the year, I’ll no longer be reading any blog in the Manosphere proper, nor reading any of the comments thereof. I tentatively plan to finish up a few topics of interest, and then move on.

Peace,

DR

I’m trying to understand the mentality behind re litigating history that seems to be everywhere online, and I thought you’d respond. (I’m not a regular reader so I’m unaware of most of your history.)

There are so many people writing online who are re-interpreting history as if re-interpreting history will make a difference in something. Nobody ever really definitively asserts how learning the secret history of the Xhosa or the Inquisition will actually matter.

In your case, you are not catholic, why are you trying to figure out catholic history? You’re not dependent on catholic narrative for your beliefs, but you just put a lot of effort into finding holes in a section of what they believe. It seemed a bit odd to me.

Your ‘top ten reasons everyone should do crossfit at least once’ styled response though is kind of confusing.

I asked you why, and you came up with 10 good reasons. I don’t think that’s really answering why, I think you’re doing the apologetics thing where you throw as many arguments as you know out in order to confuse the conversation.

For instance, ‘I’m not susceptible to the heckler’s veto’ ok, cool, who cares? Why is that important? You might as well say ‘peer pressure has no effect on me!’ Well why is that a reason to write about the RCC on the internet? It’s not like the RCC has power over you, or over narratives generally. We’re a couple hundred years past that peak.

‘It’s about truth & logic/the internet provides’ I’d like to point out, you can’t prove truth with history, because history is narrative. It just is fragmentary, perspective bound and dependent on interpretation.

Point 5. Why is the anabaptist perspective interesting? Is it sufficiently different to matter to anyone who isn’t anabaptist? There weren’t any anabaptists around in the specified time period, why would anyone trust/bother with your narrative? You aren’t going be unbiased in your reading, is there anything interesting about your bias? Does it give new perspectives?

To wrap up, I have family who think it’s very important to recognize the RCC as the whore/casually believe it, yet they still go to St. XXX for medical care. So I’ve developed this bemused attitude to people correcting/attacking the RCC as if it’s important to do so. But when I ask my family why they think it’s important they haven’t said anything that I found interesting. I thought I’d ask here because I sensed a similar feeling, and as I mentioned at the top I see this interest in litigating history everywhere, people think it’s so important and I just don’t get it.

Lucas,

Well, I think you should have led with that. Instead, I had to guess why you might be asking and so give you the most general purpose answer I could give, in hopes that something would satisfy your curiosity.

My motivations are complex, it’s as simple as that. There is no single thing that motivates me.

I answered you—a perfect stranger—honestly as to what my motivations are. You chose to respond by suggesting that I’m trying to sow confusion. That’s not very charitable (or accurate).

I’ll hold my cool with you, but you should know that questioning my integrity without a substantive cause is not a good way to start a relationship.

But, speaking of confusion, it is perfectly understandable that after I shine the light of clarity on the “historical narrative” that people would be confused. But it isn’t because what I’m saying is confusing. The confusion is based in how it could be that the sincerely and deeply held beliefs of a billion people could be based on a clear falsehood. I can see why that would produce feelings of confusion (and other emotions, like anger, fear, hostility, and regret).

I don’t know who you are, anon, and we had no prior relationship. You didn’t even read my previous writings. But, you come here implying that I need a justification to write about these topics, then disregard my honest and open response, and then insult me by suggesting I have an ulterior motive.

Now you can see why I brought up the Heckler’s Veto. It is, unfortunately, too common whenever I discuss these issues: trying to coerce me into silence rather than confronting the ideas on their own merits.

What? Sure you can. All it takes is for two people to engage in logical induction is to agree on the historical grounds and then to engage in the act of reasoning. There is no logical reason why this cannot take place. There is plenty of sociological and psychological reasons why this doesn’t take place, but it isn’t a matter of logic and reason.

You asked me for my motivations, that’s one of them. I am motivated by who I am. I’m not demanding that anyone else finds the perspective interesting or relevant. I’m simply being honest about my motivations (and implied biases). Do you have a problem with that?

What an odd question. I would think that people who openly acknowledge and confront their own biases would be more worthy of trust than those that don’t. That’s certainly been my experience.

But you shouldn’t bother with me because of trust—a fallacious Appeal to Authority. You should bother with the ideas presented because they are historically accurate accounts.

Have I correctly analyzed history without making any factual errors? If so, then you should take the conclusions seriously because they are true, not because I am the one making them (which would be an instance of the genetic fallacy).

You should never agree or disagree with me because I am the one making the argument. Nor should you ever fallaciously appeal to some other authority as your source of truth in order to disregard what I’m saying.

There is nothing wrong with refusing to “only drink milk from a Christian cow.” Jesus never commanded such an absurd thing. There is no contradiction inherent in that behavior.

Bemused or not, you’ve made your choice. That’s the important bit. You’ll never be able to say “I didn’t know,” rather you’ll say “I knew, and I chose this as an act of my own full agency.”

Above I asked “Do you have a problem with validating theology to see if it is consistent with history? Don’t you find these analyses interesting and relevant?” You didn’t answer the questions.

Now, I’m genuinely curious. Why don’t you find Rome’s foundation of sand to be interesting and relevant? Maybe we can talk about that.

Let’s be as concrete and discrete as possible. We know that Leo (and his predecessors) fraudulently presented fake Canons of Nicaea. We know that they knew that they were fake. It’s not simply a matter of “narrative opinion.” The historical record makes this unambiguous.

So what do you do, knowing that the argument behind Papal Primacy is rooted in fraud? You don’t find that even slightly interesting?

We also know, from history, that Rome did not have primacy within its own Diocese, let alone over the whole church. This is mostly unknown to most people—as it was to Jerome—but it isn’t unclear in the historical record. So what do you do, knowing that Rome did not have an unbroken line of primacy back all the way to the time of Peter? Don’t you find that even slightly interesting?

You want to know why I find all of this interesting, but I don’t understand how anyone could fail to find it interesting.

I have all sorts of motivations behind why I write but none of that is required in order to drum up interest on the topic! The topic is, IMO, inherently interesting.

Peace,

DR

Pingback: Bearing False Witness (Mini Review) - Derek L. Ramsey