Any discussion of the theology of the ancient church, apostolic succession, and church authority is incomplete without recognizing the following historical facts.

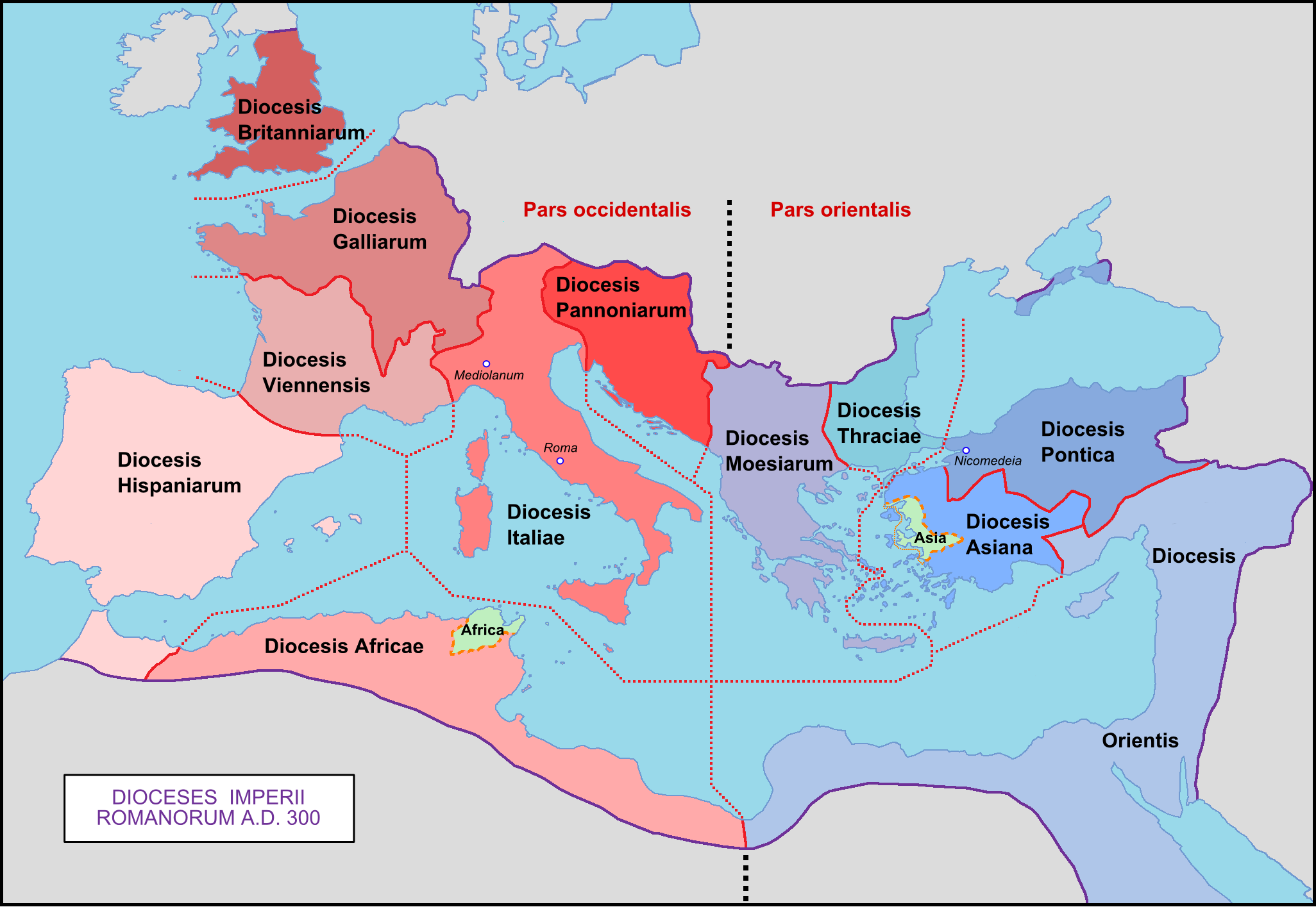

First, the Diocese of Egypt did not exist in 300AD:

Second, the Diocese of the Egypt existed in 400AD, split from the Diocese of Oriens (or the East):

These simple matters of history are, arguably, the most important facts pertaining to the legitimacy of the church today. Underlying the whole of ecumenical and jurisdictional matters is the concept that the Bishop of Rome—the Pope—has authority over the whole church, so that what he declares is law in the church. But, this was not always the case. The historical facts—through the division of Eygpt from Oriens (i.e. the East)—reveals the truth and separates fact from fiction.

The Diocese of Egypt

As shown above, the Diocese of Egypt did not exist in 300AD. It was not formed until sometime between 370 and 378AD,[1] five decades after the Council of Nicæa in 325AD. This may seem obscure and unimportant, but it unveils the single most shocking and damning set of facts regarding papal authority:

Papal Rome did not exist prior to the late 4th century.

…and…

Rome did not even have primacy within its own diocese, let alone within the universal church.

Prior to the late 4th century, there was no Roman Papal Primacy, because there was no primacy of Rome and there was no Papacy. This most persistent and most essential Roman Catholic doctrinal innovation is based on historical error. To show this, let’s go back a bit further in time.

Jurisdictional problems in the universal church—which churches got the final say in various matters—were a common feature in the 4th and 5th centuries. In 307AD, Meletius of Lycopolis unlawfully ordained bishops outside his jurisdiction. From that point until 451AD, no less than five church councils had to deal with ecclesiastical and Metropolitan jurisdictional problems, such as dealing with assigning jurisdictional and hierarchical authority between multiple Metropolitians in a single geographical unit. Most importantly, the Council of Nicaea (325AD) in Canon 6 and 7 defined jurisdictional boundaries between the Metropolitans of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem within that single province: the East (or Oriens). Specifically, the council gave Antioch jurisdictional primacy over both Alexandria and Jerusalem, citing “the custom of Rome.”

Let the ancient customs (εθη) in Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis prevail, that the Bishop of Alexandria have jurisdiction in all these, since the like is customary (συνηθες) for the Bishop of Rome also. Likewise in Antioch and the other provinces, let the Churches retain their privileges. And this is to be universally understood, that if any one be made bishop without the consent of the Metropolitan, the great Synod has declared that such a man ought not to be a bishop.

This custom of Rome would later be cited as evidence of the primacy of Rome because—by tradition—Rome has always had primacy, but as we will see this is both circular reasoning and an ignorance of history.

In 325AD, the Metropolitan seat of the Diocese of Italy was with the Bishop in Milan.[2][3][4] Milan, not Rome, had the primacy within that Diocese. The “custom of Rome” referred to Rome being under the Bishop of Milan, carving out a smaller defined and restricted geographic boundary for Rome’s Bishop within the larger diocese, while leaving the majority primacy to the Bishop of Milan. At the Council of Nicaea, it was decided that so too would both Alexandria and Jerusalem both be granted limited geographic scope under the overall majority provincial primacy of Antioch. The example of the limited authority of the Bishop of Rome was cited to solve the jurisdictional tension between three Metropolitans in a single province. Far from Roman Papal Primacy from the apostolic age, the Bishop of Rome did not even have primacy within his own diocese until 358AD at the earliest.[2]

In 370AD, Optatus of Milevus would be the first to declare that Peter was the first Bishop of Rome.[5] This was in direct contradiction to the early patristic writers, such as Irenaeus[6] and Eusebius[7], who recognized Linus as the first Bishop of Rome. The early church did not believe that Peter—an apostle—was ever a bishop of Rome, let alone a pope. This novelty would set the stage for what followed.

By the Council of Constantinople in 381, the Roman provinces were now dioceses. Sometime in the five decades that followed Nicaea and the one or two decades since 358AD, the ecclesiastical unit of the church had changed from provinces to dioceses and the civil diocese of the East had split into two (Egypt and East). No longer was there a single province containing Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria. The Diocese of the East contained Antioch and Jerusalem, while the Diocese of Egypt contained just Alexandria.

At the Council of Nicaea (324AD), the East (Oriens) contained Alexandria.

At the Council of Constantinople (381AD), Egypt (containing Alexandria) was its own diocese.

This split—between 370AD and 378AD—caused the elevation of Alexandria from its previous subservience to Antioch to the new sole primacy within its own Diocese. Furthermore, by this time—between 358AD and 378AD—Rome had claimed the diocesan primacy from Milan. These two facts would be central to the theological development that followed.

As the 4th century drew to a close, the previous jurisdictional arrangement determined by the Council of Nicaea—regarding Rome, Alexandria, Jerusalem, and Antioch—had been forgotten, ignored, or (perhaps) intentionally inverted. A year after Constantinople, at the council of Rome in 382AD, Pope Damasus I would declare:

“the holy Roman church is given first place by the rest of the churches”

Damasus was the first to successfully make this assertion.

Damasus was the first pope to refer to Rome as the apostolic see, to distinguish it as that established by the apostle St. Peter, founder of the church. In 380 the emperors Gratian in the West and Theodosius in the East declared Christianity as preached by Peter to be the religion of the Roman Empire and defined orthodoxy as the doctrines proclaimed by the bishops of Rome and Alexandria. Rome’s primacy was officially pronounced by a synod called in Rome in 382 by Damasus, who was perhaps wary of the growing strength of Constantinople, which was already claiming to be the New Rome. St. Jerome (c. 342–420) attended the synod and stayed on to become Damasus’s secretary, close adviser, and friend. Damasus commissioned him to revise the Latin translations of the Bible for what subsequently became known as the Vulgate.

Jerome—close friend of Damasus—would become his greatest ally.

Now we come to the key point, where the Nicean precedent was inverted to cement the creation of Roman Papal Primacy. In 398AD, during his dispute with John of Jerusalem, Jerome claimed that Nicaea had granted Antioch jurisdiction over Jerusalem in the diocese of the East and over Alexandria in the diocese of Egypt—as if the council granted a Bishop authority outside of his single diocese rather than solely within it—because of the custom of the primacy of Rome. Jerome’s claim—whether intentional or by accident—was an impossible historical anachronism.[8]

The primary of Rome was asserted through a misunderstanding (or misframing) of its historical lack of primacy

Combined with the political power of two emperors, Damasus and Jerome were able to fabricate the doctrine of Roman Papal Primacy out of thin air, by citing as evidence the very historical record that clearly disproved it. By no coincidence, this occurred along with the single greatest corruption of scripture—the Latin Vulgate.

The Council of Nicaea

The Council of Nicaea represents the culmination of the first three centuries of Christianity. Roman Catholicism arose in the late fourth century and purportedly represented Christianity for the centuries thereafter. It is thus important for the Roman Catholic and the church historian to tie the (modern) latter in with the (ancient) former in terms of succession, otherwise the latter stands as an illegitimate corruption, a novel interloper.

In 449AD, Pope Leo I—echoing Pope Zosimus in 418AD—would fraudulently claim that the canons of the Council of Sardica (in 344 AD) were actually from the Council of Nicaea (in 325 AD), deliberately misquoting and misappropriating them in order to bolster his claim that Rome was always chief of its diocese and to demonstrated the primacy of Rome to resolve all church disputes. In so doing, he utilized “Nicaea” to further perpetuate and cement the false doctrine of Roman Papal Primacy.

The misappropriation of Nicaea has persisted. In 1880, Father James Loughlin made the exact same anachronistic mistake in arguing for the primacy of the Pope to assign inter-diocesian jurisdictions (over the other two Petrine Seats of Antioch and Alexandria).[9] Around the same time, famed historian Philip Schaff (1819-1893), in his history of the Christian Church, incorrectly claimed that Rome had always had its own diocese. Others throughout history have made the anachronistic error by stating that Nicaea had given Alexandria the whole Diocese of Egypt (which, notably, didn’t yet exist).

Roman Catholic John C. Wright also sees the importance of establishing the link between the authority of Nicaea and the authority of the Roman Catholic Church:

I did not understand why, in principle, a theological dispute could not be resolved in the future as they always had been in the past, by synods and counsels and, if need be, general counsels. Any Christian who accepts the Nicene Creed accepts the authority of the Council of Nicaea. I do not understand how, in principle, a Christian can claim to have the right to be a Christian without submitting to Christian teaching, that is, submitting to what Christ taught.

Although we disagree with his acceptance of Roman Catholicism, we acknowledge that Nicaea at the heart of the issue. To be a Nicaean Christian of the Nicaean Creed, one must accept the authority of Nicaea as representing the whole of the church. However, as we’ve established above, Christians who accept the Council of Nicaea must logically reject Roman Papal Primacy on the basis of the “custom of Rome” that was established by the authority of that selfsame Council. If we are to accept the authority of the Council of Nicaea in their declaration of the Nicene Creed, then we must accept its authority to rely on the inferiority of Rome in resolving the jurisdictional dispute between Antioch, Jerusalem, and Alexandria.

Lest you think this is a minority view, here is what another typical modern apologist has to say about Canon 6 of the Nicaean Council:

The Catholic interpretation understands the Canon as follows:

All of the sudden, this Canon has some “teeth”. The appeal of the Council is to an ancient custom, which surely must have originated on some solid basis (i.e. not accepted simply “because it’s old”), and this basis is none other than the delegation of the Bishop of Rome. Without question, only the Catholic interpretation of this Canon satisfies the intellect and confirms the Faith, especially when we look at it in the context of the Canons of the councils immediately following Nicaea which sought to expound upon Canon 6.

The Catholic interpretation understands the canon to mean something like,

Understood this way, Canon 6 is no longer a non-sequitur; this canon now has some teeth. The appeal of the Nicene Council is to an ancient custom, which surely must have originated on some solid basis (i.e. not accepted simply “because it’s old”), and this basis is none other than the affirmation of the Bishop of Rome. Without question, only the Catholic interpretation of this canon satisfies the intellect and confirms the Faith, especially when we look at it in the context of the canons of the councils immediately following Nicaea which sought to expound upon Canon 6.

The unprepared reader might think this a perfectly reasonable explanation. But let us add the missing context prepared above to Laurentius’ quote:

Laurentius’ “Catholic interpretation” was not factually wrong, but it was a grossly misleading understanding because of what it left out. When we add the missing context, it becomes immediately obvious that the ancient Roman precedent was the limitation of its ecumenical jurisdiction within political provincial (prior to Diocletian) and diocesan (after Diocletian’s reorganization) Italy.

Just like Loughlin and Schaff, we can see the anachronism hard at work in Laurentius’ apologetic:

Like those who came before him, Laurentius simply does not realize that in 325AD, Egypt did not exist as either a political or ecumenical entity. But Italy did and it wasn’t under the rule of Rome. This isn’t the kind of response you give if you know that Egypt wasn’t a diocese. And that’s not the only diocese that didn’t exist:

While the Bishop of Rome is properly Bishop of the Roman Diocese, as Successor of Peter he also has a final jurisdiction over all other churches as well.

There was no “Roman Diocese” to which the Bishop of Rome was assigned.

Thus, we agree with Timothy F. Kauffman who states:

Thus, in the mind of the Roman Catholic, the canon is plainly a matter of the antiquity of Roman Primacy.

Of course, in the absence of any historical context—civil or ecclesiastical—such a reading may be plausible, although the two different Greek terms for “custom” in the original do not lend themselves to that interpretation. In any case, we do not have the luxury or the prerogative of simply extracting Nicæa from its historical context. Such extractions provide a notoriously unreliable basis for understanding history, and that is certainly the case here. An examination of the civil and ecclesiastical context of Canon 6 actually yields the very opposite of Roman Catholic claims. What was being “reiterated now by this Nicene Council,” was the fact that the jurisdiction of the bishop of Rome was quite limited indeed.

(NOTE: Much of the content of this article is a summary of Kauffman’s article. Do give it a read.)

Papal Authority

Under Nicaean Christianity, the church was not unified as a single institution under a single head—that is a pope. Prior to the late 4th century, the head of the church was solely Christ. In the late 4th century, Christ was replaced by the Pope. No Roman Catholic church council or pope has any authority over the body of Christ.

The pope is not magically protected from bad doctrine because God placed him as the head of Christianity. Those Roman Catholics who smugly declare that the church cannot be corrupted because the Pope is God’s infallible agent are badly mistaken. The very foundation of their doctrine is based on a corrupted historical anachronism: the Bishop of Rome wasn’t even the head of the early church, because Rome itself was not the foremost member of churches. God did not prevent the Roman Church from arising because it was prophesied (see the section “On Eschatology” here).

Through something as simple as…

The Diocese of Egypt didn’t exist at the Council of Nicaea

…we get…

The doctrine of Roman Primacy is an historical anachronism

…and this leads us to today, where Catholics are confused about why a Pope led them into doctrinal error, having failed to grasp that their Pope isn’t the head of Christianity, let alone divinely protected from error. He will, like the Protestant churches before him, continue to pursue error. Don’t assume this can or will improve.

Footnotes

[1] Due to this being so far in the past and with much documentation lost, the dating is somewhat uncertain. Edward Gibbon suggested in “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” (Editor: George Davidson; Kindle Edition, location 3290) that Oriens split in c.360, “about” 30 years after the establishment of Constantinople in 330. A.H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire 284-602, Vol 3, p.390 gave a somewhat later estimate:

However, using the evicdence from primary sources gathered by Clyde Pharr (in The Theodosian Code and Novels, and the Sirmondian Constitutions, 1952, p.351,356), the change must have happened no earlier than 370 (or maybe 373) and no later than 383AD. See Timothy F. Kauffman’s podcast notes (see the PDF here):

But it must be earlier than 383, because the Council of Constantinople (381) was already using the new diocesan arrangement.

Wikipedia gives further support by citing a date of c.381 per Palme, Bernhard (2007). “The Imperial Presence: Government and Army” (in Bagnall, Roger S. (ed.). Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700. Cambridge University Press. pp. 244–270), while the “Oriens” entry in the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Vol III. (Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford University Press. pp. 1533–1534) says that the split occurred under Valens’ reign (364–378).

This suggests that the split occurred between 370 and 378.

[2] Athanasius, “Apologia Contra Arianos“, Part II, chapter 6, paragraph 89

[3] Athanasius of Alexandria, “Ad Episcopus Aegypti et Libyae“, paragraph 8

[4] Athanasius of Alexandria, “Apologia ad Constantium“, 27

[5] Optatus of Milevis “Adversus Parmenianum“, Book 2, Chapter 2

[6] Irenaeus “Against Heresies“, Book 3, Chapter 3.3

[7] Eusebius, “Church History“, Book III, Chapters 2, 13, 21

[8] Jerome, “To Pammachius Against John of Jerusalem“, paragraphs 4, 10 and 37.

[9] James Loughlin, “The Sixth Nicene Canon and the Papacy”, American Catholic Quarterly Review, vol. 5