All this bears a striking similarity to a point which Dr. James White has made before, most notably in his 1997 debate with Gerry Matatics. In that debate he said that sola scriptura is a “normative condition” of the church that does not exist “during times of enscripturation.” It only shows up when the canon is closed. The anonymous “TurretinFan” made the same point in a more recent debate with William Albrecht, when he said that sola scriptura is “what we do with the Bible once we have the Bible.” It’s a clever argument, to be sure. It tries to get around the fact that the Church must first tell us what the canon is, by saying that sola scriptura did not exist then anyway. The canon needed to be written first. Then it needed to be codified. But then, once all that was done, sola scriptura took over and we did not need these external authorities any longer. The problem with that argument is that it leaves at least four things unexplained. Let’s look at those four things, shall we? But before we do that, let’s build start with question 0. I start with this question because like all metaphysical presumptions, it’s more important than the four questions he explicitly asked. Recall what I wrote: I have already challenged this with regards to the canon, upon which virtually all of Wright’s arguments rest. Were he to hold in abeyance that the church had the authority to define canon on the basis of historical contradiction, then his case would collapse. I believe this to be the case. John C. Wright claimed that if he set aside any disputed fact between Protestants and Catholics, what was left was Roman Catholicism. But I retorted that the very basis of the authority to determine biblical canon is itself based on historical contradiction. Wright also says: Where indeed? Wright rejects sola scriptura because its infallibility is a logical deduction from the axiom that it is the Word of God. This is not acceptable to him. He rejects internal attestation because it is axiomatic (a form of circular reasoning). But so is papal infallibility when viewed as internal attestation! Logically, if one is to reject sola scriptura because they require Bible canon to have external attestation, then one must also reject sola verbum dei—the Word of God revealed in scripture, tradition, and the Magisterium—because it also requires external attestation. Either it relies on internal attestation and is thus axiomatic circular reasoning or it requires external attestation and should thus be rejected. Since sola scriptura and sola verbum dei are mutually exclusive, we arrive right back where we were in part 4: a stalemate, where subsequently examining the evidence does not favor the Roman Catholic. Except this is not precisely true. By its own historical actions, the Protestant, Anabaptist, and Primitive Church do not strictly require a universal canon, but the RCC lives and dies on its authority to rigidly define it. While sola scriptura is merely circular reasoning—by nature of being axiomatic—sola verbum dei is a self-refuting contradiction and the RCC’s existence as a denomination is premised on that contradictory claim. Either sola verbum dei is self-refuting by logical contradiction (external attestation required), or else it logically reduces its epistemology to the axiom sola ecclesia: “Rome is the true church established on Peter and the Popes are his successors” (internal attestation only). This is damning either way. Having a church to tell us what the canon provides us with no advantage at all. Indeed, the Roman Catholic view of canonization leads to a self-refuting contradiction. Furthermore, If the message is authentic (in reality), then no authority can make it authentic: it is authentic regardless. If the message is not authentic (in reality), then no amount of apostolic authority or faith can override that. Authority is irrelevant to the reality of canonicity. An authority can merely confirm for another what the authenticity already was: it is at best descriptive and not prescriptive at all. The only roadblock is a personal and arbitrary one: do you demand an Appeal to Authority. Rather than authority, it is the evidence (if any) that matters. I then go on to note that the supposed required method of canonization by authority did not take place with the Old Testament. The formation of the Old Testament was a bottom-up, community-based approach, not a top-down, episcopal approach. Most importantly, the Catholic canon isn’t canonical. Jesus, the apostles, and the early church mostly used the Greek Septuagint. And, this is critical, they shared the same canon with the one used by the Pharisees. In particular, Jesus quoted from every section of the Pharisee’s canon. In particular, Jesus never quoted from the deuterocanonicals, which the Roman Catholics consider to be canonical. Regardless, the Catholic canon ultimately chosen is not identical to the list of books in any extant versions of the Septuagint or any known formulation of the Hebrew/Aramaic scriptures. Even if Jesus considered the deuterocanonicals to be canonical, the canon the RCC chose is likely not the same one Jesus had access to. Prior to the church councils that canonized the deuterocanonicals, they had never been canonized by anyone, Jewish or Christian. The most important act of canonization by the Roman Catholic Church got it wrong. Yes, that’s right. For all its vaunted authority, it chose a canon that was different than the one that Christ used! Oh, and don’t forget that they chose the wrong translation—the Latin Vulgate—as the official Bible of the church, a translation with numerous important errors. Roman Catholicism is as equally bad at infallibly canonizing “The Living Voice” as they are at defining the list of infallible ex cathedra statements and an infallibly defined list of ecumenical councils. For all their authority, they have never been able to do any of it. Meanwhile, Jesus demonstrated that he was perfectly comfortable flexibly working with a restricted canon, such as that of the Sadducees or Samaritans: The lack of any rule or standard explaining how to make a canon makes it less—not more—likely that one should make a canon using authoritarian rules and standards. Jesus, when given the opportunity, declined to provide any. When the Samaritan woman asked Jesus about the rules for where to worship (the mountain or in Jerusalem), Jesus responded that worship will be “in spirit and truth.” Recognizing the Word of God is likewise governed by the Holy Spirit, not rules and regulations. As for the New Testament, the Roman Catholic church did a bad job with that too: We have two evidentiary starting points. The first, historical, shows that the Old Testament and the deuterocanonicals were formed through a flexible bottom-up, community-based sacred tradition. The second, internal, shows that Jesus did not demand a canon be made. Logically, Occam’s Razor suggests that the same applies to the New Testament. Up until the middle of the 4th century, this is precisely what we see. Even Athanasius, writing in AD 367, gave a different canon from the one later canonized by the Catholic church at the Council of Trent in the mid-1500’s (and he is not the only one to do so). The error, if there is one, appears to be attempting to canonize the scriptures at all: the act of canonization was itself a corruption. … The RCC more-or-less invented the concept of universally canonizing the scriptures. By the weight of the evidence and its own admission, it had never been done before. It is logical (and perhaps tautological) that if one rejects the authority of the RCC that authorized the canon, that they reject the RCC’s authority to authorize the canon. And they do! But rejecting the authority of canonization is not the same as rejecting the authority of the canon, nor does it imply requirement to accept or reject a universal canon (for that would be circular reasoning). The RCC claim to the authority to determine a canon is a circular argument. It ultimately relies on the message it is authenticating to derive its authority to do so (even if you accept for sake of argument the messenger chain-of-custody for the message). If the messenger lacks the authority to canonize the message, then the act of producing a canon is logically a corruption. By showing this independently (as seen in the historical evidence) and internally (by examining Jesus’ own actions), the corruption becomes more evident. So, no, we do not need an infallible church authority to define canon before being able to apply sola scriptura. The very method of “authoritative” canonization that the Roman Catholic Church uses has no valid basis and is demonstrably wrong anyway. As sola scriptura implies, the identification of scripture qua scripture is self-evident. God’s word is self-authenticating. Even Reformed scholar Michael J. Kruger concedes that the literacy rate among Christians in the early centuries of the church was somewhere between ten and fifteen percent. How can sola scriptura function if such large numbers can’t even read the Bible in the first place and must rely on other authorities to tell them what it says and how it is to be understood? I’ve never understood the purpose of questions like these. Is the concept of Roman Catholic authority invalid because there exist persons with profound developmental disorders that result in extremely low intelligence? If sola scripture were false because someone could not receive the Word of God in written form, then would the blind be excluded from faith? These are absurd premises. Why should the ability to read matter at all? The ability to read is related to the ability to hear, as both are rooted in one’s intellectual abilities. Whether oral or written tradition, this objection applies to both equally. Nor was this the standard in the Old Testament with the written Law. God expected each Hebrew to follow the law whether or not he could read the words themselves or understand it orally when it was read. Even when the Word of God was temporarily lost, God still expected it to be followed: The original messengers of the Old Testament and deuterocanonicals are largely unknown. There is no documented chain-of-custody, even a questionable one. Even 2 Kings 22 describes how the Book of the Law was found after a period of disuse. We do not have sufficient evidence to authenticate the source of those texts, as the original messenger is not known. It is unclear why the standard-of-evidence used for them is different for the New Testament. There was no chain-of-custody nor authenticating authority for the Word of God. Yet Jesus still expected each and every Jew to follow every last word. Scripture is not true because of sola scriptura. Rather, sola scriptura is true because scripture is true. The Word of God is not contingent on the condition of man. Sola scriptura is a necessary inference. But let’s try to answer the question directly anyway. Most people are natural followers. Even among Protestants, not everyone is supposed to be their own leader. Protestant leaders may be individually called, but that doesn’t imply that everyone is called to lead. It has always been the case that the majority of people need to be led. The universal ability to read, write, or understand scripture has never been a requirement. But it does not logically follow from this that a central authority is required (or even an authority at all). Wrapped up in this question is the implication that following God is difficult and doing the right thing can’t be determined without a high intellectual ability. I simply don’t agree with that. Illiterate persons have been following God just fine for centuries. The problem isn’t those who can’t read and write, it’s with those who can. Much more will be asked of those who have been given much. So I spin the question around: what good is church authority when all of those men and women have been doomed because Roman Catholic authorities taught them erroneously… or worse, put them to death? Compared to this, the lack of literacy is a minor logistical problem. You don’t find any passage in the Bible that says we are to be governed by the Bible alone. Instead, we find texts, like 1 Tim. 3:15, that tell us about the authority of the Church. This is a mind-boggling objection. Here is the citation: I write these things to you, hoping to come to you shortly. But if I am delayed, I am writing so that you know how a person must conduct themselves in the household of God, which is the church of the living God, the pillar and foundation of the truth. Why would he cite this verse which specifically mentions following the written instructions on how to conduct oneself? As stated under Question 0, the assumption, unless otherwise stated, should be that the method of canonizing the New Testament would be the same as the canonizing of the Old Testament. Jesus never established a new canon or method of canonization. Thus, the Roman Catholic church must not use its authority to tell us what canon is before using sola scriptura. That’s not how the Old Testament worked, so it can’t be how the New Testament works. Why would he cite that the household—people—of God are the pillar and foundation of the truth if he wanted to deny that the people are the foundation of truth? This is a very Protestant understanding, so it is curious that he would cite this. The Old Testament was formed by a bottom-up community driven approach, which is exactly what is being described here. Completely absent is any mention to hierarchical authority, let alone a pope or episcopate. This is especially ironic, because 1 Timothy 3 is about how deacons and overseers should conduct themselves. These were written instructions for the deacons and overseers, so they would conduct themselves appropriately as members of the whole body of the church. Rather than identifying the overseers and deacons with the pillar and foundation of the truth, it is the whole church that is! It was the overseers and deacons who had to be given written instructions. They were not being set up to tell the congregation what to do as authorities on truth, but rather they were being told how they must conduct themselves, submitting themselves (per Ephesians 5) to the church, the latter of which is the source of truth. And, its worth noting, that it is this section of scripture that insists that deacons and overseers in the church are expected to be married and have children. Instead, we find people like Ignatius of Antioch telling us, “You make sure you listen to the bishop.” Why did we have to wait for James White to tell us that sola scriptura took over when apostolic authority left off? For when I pressed him on it, Dr. White was not able to tell me of one single person, before himself, who made that point. Now Reformed apologists all ape something Dr. White said in 1997 only when Mr. Matatics forced him to concede that the apostles did not practice sola scriptura. The proper question is whether or not sola scriptura is definitively described, not whether the term-of-art itself it discussed. After all, I would certainly be willing to agree to discard any and every doctrine or dogma described by a non-biblical term-of-art (e.g. The Real Presence; Sacrament) if the Roman Catholic will agree to do the same. Notice what this would mean. If we rejected every term-of-art not found in scripture or the early patristic writers, what would you be left with? Scripture alone. That’s the whole point. But, of course, Roman Catholicism adamantly refuses to discard the doctrines and dogmas that are not spoken of by scripture or the early patristic writers (e.g. Papal Infallibility; Marian dogmas). They insist that the “seeds” of these are found in the earlier works. So by the same epistemological standard, I also refuse to discard sola scriptura as a matter of principle. As soon as Roman Catholicism is willing to hold itself to the same standard that it wants to hold me to, then we can have a conversation. Until then, I have no interest in double standards. But, importantly, even if sola scriptura (the semantics, not the terminology) were not necessarily implied by scripture itself, much more than the “seeds” of sola scriptura are found in scripture and the early patristics. Prior to the late fourth century, Irenaeus insisted that the entire corpus of what was revealed as the Word of God was written down (see: Irenaeus, Against Heresies, Book I, Chapter 10 and Book II, Chapter 5). When he spoke of heretics, Irenaeus described how the heretics went beyond what was written into their oral traditions (see: Irenaeus, Against Heresies, Book I, Chapters 8 and 9). It is simply not true that we do not hear about sola scriptura in the patristic writings. These are explicit references to written tradition being the sole Word of God. Now even as the early writers wrote of using only scripture, at the same time we don’t hear anything about Roman or Papal supremacy until the late fourth century. For much of the fourth century, Rome wasn’t even the head of its own diocese, let alone the whole church! If Rome didn’t have primacy, then the entire church didn’t believe in Roman primacy. Full stop. Thus, the “authority of Rome” is an historical myth, an anachronism. The alternative to sola scriptura is not only not attested to at all, but is actively attested against. Sola ecclesia is a logical and historical impossibility. Sola scriptura is, in actuality, the only viable “choice” if one cares about being deep in history, for to be deep in history is to cease to be Roman Catholic. If the Roman Catholic can come up with a viable historical alternative to sola scriptura, I’ll hear them out, but until that point I’ll avoid the myths and stick with the only possible option. For a detailed discussion comparing sola scriptura and sola ecclesia, see the series “The Visible Apostolicity of the Invisibly Shepherded Church” by Timothy F. Kauffman. For all that time, Christians thought that Baruch was canonical scripture. For all that time, they thought that Tobit was the inspired word of God. If the Church had the authority to recognize what books were in the canon, how did they get it wrong, and why was Martin Luther the first to figure that out? Where in the Bible did Martin Luther learn that Wisdom shouldn’t be in the Bible? If, once the canon is settled, we’re supposed to follow scripture alone, how is it that scripture gets removed from scripture? Unless there are satisfactory answers to questions such as these, Protestant attempts to defend sola scriptura will only create more problems than they solve. First, by including the deuterocanonicals, Roman Catholicism got the canon wrong for more than a millennium. That’s an indictment on Roman Catholicism, not the early church (prior to the late 4th century) or anyone else, including Luther. We don’t blame the victim—the established canon—for the faults of the perpetrator. Second, as we noted above under Question 0, Roman Catholicism still has the wrong canon. Somehow, despite its infallible authority, it managed to err in the dogmatic declaration of the canon. Third, Roman Catholicism got by just fine for more than a millennium without (supposedly) needing to invoke authority on an official canon. Fourth, it’s not like the canon is helping Roman Catholics. Only 6 or 7 passages of scripture have ever been infallibly interpreted. Reverend Augustine Di Noia, O.P., Secretariat for Doctrine and Doctrinal Practices, in Washington, D.C. asked an unnamed eminent theologian which verses Rome had interpreted infallibly, who then deferred to Raymond Brown’s article on Hermeneutics in New Jerome Bible Commentary. Here is the letter: Whether the intention was to define the sense of Scripture in these passages is a difficult question[s]. It is difficult, also, to say exactly what was defined—was the intention only to exclude a particular false interpretation, and if the intention was to say something positive, did the Pope or Council mean that this was the only meaning of the text?” Or consider how Roman Catholics use Tobit as scripture, yet Tobit 12:12-15 has the angel presenting our prayers to God as “incense.” Later, the angel Raphael exhorts them to give their blessings, songs, praise, and thanks to God. This is the same as Psalm 141:1-2. Yet, Roman Catholics say that this means we can pray to angels. Having an authoritative canon certainly does not help with reading comprehension or infallible interpretation. Having the Roman Catholic authority to define canon has not actually provided anything of value to date. At best, it has clouded the issue by invoking by a fallacious argument from authority rather than applying reason or revelation. At worst, it made a grave error. Fifth, the main reason that the church has been wrong about the number of books in the canon since the late fourth century is this: a non-apostolic church tried to canonize Christian scriptures in the first place. Or, put another way: Why was the Man of Lawlessness in Thessalonians and the Beast of Revelation wrong about the number of books of canon? Such a mystery. I guess we’ll never know why Satan didn’t establish a valid canon. As with all of these questions, this question is premised on the false notion that Roman Catholicism is apostolic, rather than having originated in the late fourth century. As soon as one familiarizes oneself with the history of the church, these questions just become irrelevant. It’s simply not important that the apostate church has gotten the canon wrong since ~350AD. This is why I cited Irenaeus, an early writer who rejected the validity of oral tradition. It’s why I cite Cyril of Jerusalem, who wrote in the middle of the fourth century, right at the cusp of the rise of Roman Catholicism. He taught sola scriptura. Yet, he didn’t follow through with his own teachings. Consider this rebuttal by a Roman Catholic apologist: At first this could be viewed as Uncatholic from a Protestant point of view, but only because their assumption is that Tradition does not come from the same deposit of faith as Scripture. According to the Second Vatican Council… … As seen here, the Church teaches a close connection between both Scripture and Tradition. Since the two come from the same deposit of faith, then we can say honestly that we are fully in harmony with what St. Cyril says here. The Protestant assumption behind using him to support their case comes from a faulty understanding of Sacred Tradition and the teachings of the Church. Did Cyril teach sola scriptura? Well, according to the apologist, he couldn’t be because of… the Second Vatican Council. Talk about a citation that begs-the-question! This is especially ironic, because a growing number of traditional Roman Catholics do not consider the Second Vatican Council to be ecumenical and authoritative. Regardless, this is the Roman Catholic Axiom in action, which we last saw in action by Roman Catholic David Waltz in “Sacraments, Part 3: Baptismal Regeneration.” It doesn’t matter how close is the connection is between scripture and other traditions. When Cyril says that scripture is required for “even a casual statement,” then scripture is required whether or not you have other traditions to go along with it. If you have some other tradition that isn’t found in scripture, then it’s a violation of what Cyril says. It doesn’t matter at all how close the connection is if there is no connection to begin with. Scripture is fundamental. Like the Roman Catholic church and canon, the same objection applies to Cyril: St. Cyril taught the Eucharist is the true flesh and blood of Jesus First, Cyril taught error because he didn’t practice what he preached. He went outside of the scriptural warrant that he insisted upon. He taught that scripture was required, but then embraced heretical doctrines that were not supported by scripture. This is the exactly same thing that caused the Roman Catholic Church to be wrong about the canon for more than a thousand years. This is the problem with rejecting sola scriptura. Without an anchor, you cannot tell what teachings are correct and which are heresy. You are left to cherry pick what you want and rejecting the rest (i.e. selection bias and circular reasoning). This is especially important with Cyril, because he taught things that Roman Catholics reject. Moreover, authority doesn’t help, because you need infallible lists that do not exist. Scripture is the only anchor that tells you which teachings of Cyril are right and which are wrong. Second, Cyril didn’t teach that the eucharist was the “true” (literal?) flesh and blood of Jesus. As we saw in “The Eucharist, Part 24: Cyril of Jerusalem,” Cyril in 350AD was the first patristic writer to consecrate—through the prayer of thanksgiving—the bread and wine before it was offered. In doing so, he was the first patristic writer to make the sacrifice propitiatory. That is his primary contribution to the development of the Roman Catholic Eucharist. But, (1) He still viewed the elements as spiritual symbols (antitypes) of Christ’s body and blood. The bread and wine were the physical reality, while the body and blood were the spiritual reality. The physical was a symbol for the spiritual. (2) He offered—as a sacrfice—the bread and wine before the eucharist received the words of institution in the epiclesis (“This is my body. This is my blood”). The ancient structure (or ordering) of the liturgy remained unchanged. (3) His eucharist was still a tithe offering, which included ointment. (4) He described the sacrifice we offer as the one found in Malachi: a sacrifice of praise. It never even occurred to Cyril to insert Christ’s sacrifice into the sole sacrifice prophesied by Malachi that the church now offers. So while we acknowledge the important role that Cyril played in corrupting the ancient eucharist and “sacrifice of the dismissal” during the late fourth century, it is simply not true that he taught that the eucharist was the true flesh and blood of Jesus. Cyril’s words remind me of one of the quotes by the Roman Catholic who inspired the series on the Eucharist: The typical Roman Catholic apologist is quick to cite Cyril as the source of the body and blood of Christ in the eucharist as a propitiatory sacrifice for sin. And yet, I’m lectured in no uncertain terms about the importance of the words of institution, the very words that Cyril himself failed to use during the sacrifice! I suppose Cyril must be famously known for calling Jesus a liar. Remember when Cyprian said that Jesus didn’t offer his literal blood at the Last Supper when he said “this is my blood,” because Christ had to be crucified first before believers could drink his blood? I guess Cyprian was calling Jesus a liar too. Where have I heard that before? Oh, that’s right: It’s the spirit of the age: no need for discussion, explanation, or reason. Just assert that you are right and end any possibility for discussion or debate. The question of canon ultimately doesn’t matter because to the Roman Catholic it isn’t actually up for debate. The issue has already been settled dogmatically, and no matter what arguments you raise, the dogma is unassailable. Cyprian, Irenaeus, and Cyril are all required by the church to supports its doctrines and dogmas. No dissent is allowed. Roman and Papal Supremacy didn’t exist in the middle of the fourth century, but that won’t stop the Roman Catholics from asserting that it did exist. They are obligated to believe it. The same thing applies to the question of canon. I could write a thousand articles and cite a thousand sources, and it wouldn’t—couldn’t—ever change the dogmatic declaration of canon. Don’t get distracted by the questions and answers. They don’t really matter. That’s not the line that divides us. If you think this conclusion is faulty, it has yet to be proven wrong. No Roman Catholic has ever responded to my claims without ultimately resorting to dismissal, ad hominem, non sequitur, and/or circular reasoning. There is always a first time, I guess. I hope my cynicism is proven wrong! No. Because of this, all that follows is merely an academic/intellectual exercise. It’s mostly irrelevant. At worst, it is a minor logistical problem that is easily overcome. It isn’t a hurdle to sola scriptura. 1 Timothy 3 fully supports sola scriptura in that it asserts that leaders must follow the written instructions and that truth comes from the whole church, not its leaders who must bind themselves to the church (not the other way around). Also, church leaders must be married and have children. We do in the writings of Irenaeus and Cyril. Because the Roman Catholic Church is apostate. What it thinks about canon has no validity.Question 0

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Question 4

Summary

Sola Scriptura

Scott Eric Alt

The doctrine of sola scriptura is not about a list of books, but the principle that all doctrine must come from scripture. In other words, all doctrine must come from a certain type of revelation, namely, inscripturated divine communication. The codification of the canon as a list of books is subsequent to the receiving of texts as scripture, not prior to it; and saying that the rule of faith is contained in the sixty-six book canon of scripture presupposes this codification as subsequent.

0. Must the church first tell us what the canon is before using sola scriptura?

Any historical fact which was disputed, I held in abeyance.

But if not from the Church, from where would this Magisterial authority [to canonize infallible scripture] come?

Reviewing Wright’s Universal Apologia, Part 4

Reviewing Wright’s Universal Apologia, Part 4

Reviewing Wright’s Universal Apologia, Part 4

Scott Eric Alt

1. If that were true, what about the many Christians who could not read?

Reviewing Wright’s Universal Apologia, Part 4

Scott Eric Alt

2. If that were true, why would God not have told us about sola scriptura somewhere in the biblical text?

1 Timothy 3:14-15

Scott Eric Alt

3. If that were true, why do we not hear about it in the Church Fathers?

Scott Eric Alt

4. If that were true, why was the Church wrong about the number of books in the canon for 1200 years?

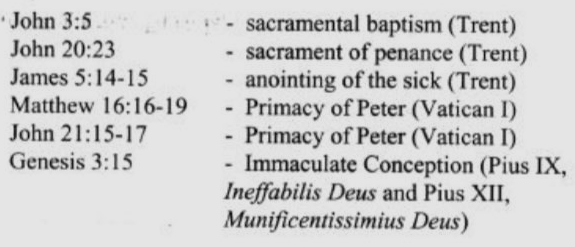

Following Raymond Brown, I would think that a case could be made that the Church has defined something about the correct interpretation of the following seven passages:

Da Pacem Domine

“For concerning the divine and holy mysteries of the Faith, not even a casual statement must be delivered without the Holy Scriptures.”

So the question becomes “which view did St. Cyril hold to?” This is when we start looking at various examples of his teachings. Well, what did St. Cyril teach?

Bardelys the Magnificent

The Host is Christ and there is no arguing against it. I find it funny that Protestants and other anti-Catholics will argue scripture ’till the cows come home, agonizing over the meaning of every tiny little word, but completely skip over Jesus saying “this is my body, this is my blood.” Those are His exact words. He didn’t say “this is like my body.” No. He said “this IS my body. This IS my blood” No ambiguity, no parables, no ********. Next to the Passion, the Last Supper was the most important thing Jesus did and he wasn’t screwing around that night. The host is Christ and that cannot be argued, unless you want to stand here and claim Jesus to be a liar at His last supper.

The Host is Christ and there is no arguing against it.

0. Must the church first tell us what the canon is before using sola scriptura?

1. If that were true, what about the many Christians who could not read?

2. If that were true, why would God not have told us about sola scriptura somewhere in the biblical text?

3. If that were true, why do we not hear about it in the Church Fathers?

4. If that were true, why was the Church wrong about the number of books in the canon for 1200 years?