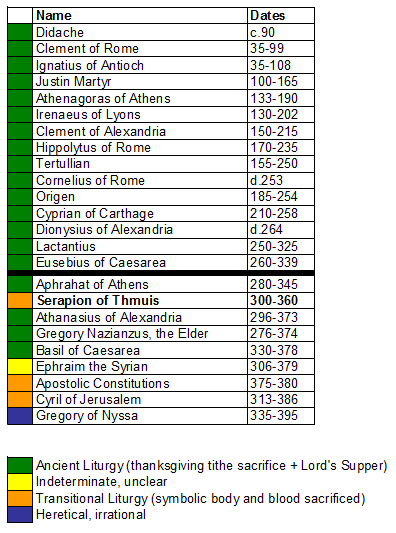

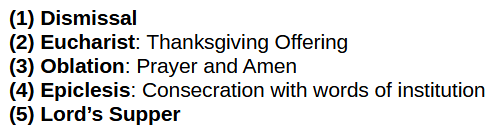

The original liturgy:

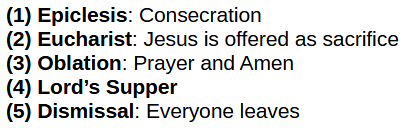

The Roman liturgy:

Serapion of Thmuis

There is not a lot to discuss with Serapion, so I’ll quote this large portion from his Sacramentary, which dated to around 353AD.

We offer also the cup, the likeness of His Blood, because the Lord Jesus Christ took the cup after He had eaten, and He said to His disciples, ‘Take, drink, this is the new covenant, which is My Blood which is being poured out for you unto the remission of sins.’ For this reason too we offer the chalice, to benefit ourselves by the likeness of His Blood. O God of truth, may Your Holy Logos come upon this Bread, that the Bread may become the Body of the Logos, and on this Cup, that the Cup may become the Blood of the Truth. And make all who communicate receive the remedy of life, to cure every illness and to strengthen every progress and virtue; not unto condemnation, O God of truth, nor unto disgrace and reproach!

For we invoke You, the Increate, through Your Only-begotten in the Holy Spirit. Be merciful to this people, sent for the destruction of evil and for the security of Your Church. We beseech You also on behalf of all the departed, of whom also this is the commemoration: – after the mentioning of their names: – Sanctify these souls, for You know them all; sanctify all who have fallen asleep in the Lord and count them among the ranks of Your saints and give them a place and abode in your kingdom. Accept also the thanksgiving of Your people and bless those who offer the oblations and the Thanksgivings, and bestow health and integrity and festivity and every progress of soul and body on the whole of this Your people through your Only-begotten Jesus Christ in the Holy Spirit, as it was and is and will be in generations of generations and unto the whole expanse of the ages of ages. Amen.”

Citation: Serapion of Thmuis, “The Sacramentary of Serapion.” Prayer of the Eucharistic Sacrifice

But there is another popular version of this floating around:

Citation: Joshua Charles, “Becoming Catholic Quote Archive.” St. Serapion of Thmuis

This is clearly a different translation, but notice that the part in bold exists in the latter, but is not included in the former.

In the first version, there is a distinct (2) thanksgiving, (3) oblation, and (4) invocation. It never says that the bread—the likeness of Christ—is sacrificed. However, it does say that the consumption of the consecrated bread is for the remission of sins, something we saw in Part 24, Cyril of Jerusalem, Serapion’s contemporary.

The second quote, however, is unambiguous.

What are we to do with this? I don’t know if the part about sacrifice is original, but its inclusion is consistent with the purpose of the bread being for the remission of sin, so it probably doesn’t matter either way. In treating the Lord’s Supper as a sacrifice for the remission of sin, Serapion (353) joins Cyril (350), Gregory Nazianzus the Younger (383), and the unknown author of the Apostolic Constitutions (375-380). And of course there is Gregory of Nyssa who said, by 382, that Jesus sacrificed himself at the Last Supper, that he was crucified, dead, and in the grave as he was serving his dead flesh to his disciples. It seems like Serapion, seeing the trend of innovations from others, wanted to contribute in his own way too.

Sidenote: Although I’ve mostly left off any discussion throughout this series about whether various documents are reliable (or even actually written by the people claimed to have written them), it is always worth noting that one of the reasons we favor sola scriptura is because the Bible is much better attested than most of the early church writers. Throughout this series, we examine what the early writers wrote to the best of our knowledge, but we don’t assign to them the level of confidence that we assign to actual scripture.

One additional note: Serapion is also advocating for prayers for the dead as part of the Eucharist and Lord’s Supper. Perhaps not by coincidence, his contemporary Cyril did the same thing (and he received resistance to it). It is interesting how prayers for the dead developed in conjunction with the body of Christ being offered as a sacrifice for the remission of sin right around 350AD.