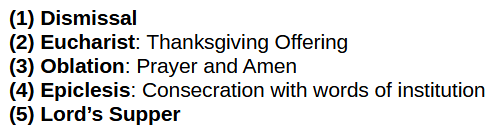

The original liturgy:

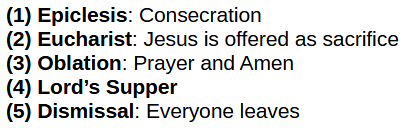

The Roman liturgy:

Augustine of Hippo (354 – 430)

Augustine became a Roman Catholic Christian in 386, so he is unique in this series in that he was of-a-sorts fully Roman Catholic. And yet he is known for holding a lot of Protestant positions. It will be interesting to discover his views on the Eucharistic liturgy.

A Google search shows that FishEaters’ quotations are extremely popular among copy-and-paste apologists. The first quotation (shown below) is attributed to “Explanations of the Psalms 33:1:10”, but it is not found in “The Exposition on Psalm 33” on New Advent, nor in the full “Expositions on the Psalms.” There is no indication where the translation comes from. After searching, I found an explanation. Ironically, my citations below are more accurate than dozens (or more) apologist sites. How disappointing that many blindly copy citations without checking them! This shows loose or non-existent academic integrity: a commitment to ideology over truth.

Citation: “Explanation 1 on Psalm 33” on p. 21 of Vol. 2 of Expositions of the Psalms, translated by Maria Boulding, OSB.

Citation: “Sermon 227” on p. 254 of Vol. III/6 (Sermons 184-229Z on the Liturgical Seasons), translated by Edmund Hill, OP.

Citation: “Sermon 272” on p. 300 of Vol. III/7 (Sermons 230-272B on the Liturgical Seasons), translated by Edmund Hill, OP.

The ancient liturgy states that the consecrated bread is the symobolic body of Christ and the consecrated wine is the symbolic blood of Christ. It also states that the unconsecrated bread and wine are sacrificed as part of the tithe offering. The Roman liturgy merges and alters these by sacrificing the consecrated bread and wine and viewing them literally instead of symbolically as the body and blood of Christ.

These three quotes are selected by Roman Catholic apologists because they make it appear as if Augustine is describing transubstantiation of the bread into the literal body of Christ in the Roman liturgy. But, Augustine just paraphrases what Jesus himself had said: “this is my body; this is my blood.” As the grammar of a literal and canonical metaphorical statement are the same, the words themselves do not show that Augustine is treating the elements literally instead of as a metaphor or symbol. Fisheaters has not provided enough context to show that Augustine has diverged from the ancient symbolic understanding of the consecrated bread and wine.

Roman Catholics love to talk about how foolish, ignorant, lying Protestants don’t interpret John 6 correctly. In John 6, they conclude that Christ offered his literal body and blood in the bread and wine. FishEaters did this in her article “The Eucharist” where she said:

proves that Jesus was speaking only symbolically. But how can He mean BOTH

AND

How can both of these verses be true if understood in the sense that Protestants understand them? Is He schizophrenic? A liar? A contradicter of His own words? Did He change His mind in between verses 58 and 63?

Let’s see what Augustine has to say:

….But when our Lord praised it, He was speaking of His own flesh, and He had said,

Some disciples of His, about seventy, were offended, and said,

And they went back, and walked no more with Him. It seemed unto them hard that He said, Unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man, you have no life in you: they received it foolishly, they thought of it carnally, and imagined that the Lord would cut off parts from His body, and give unto them; and they said, This is a hard saying.

…

But He instructed them, and says unto them,

Understand spiritually what I have said; you are not to eat this body which you see; nor to drink that blood which they who will crucify Me shall pour forth. I have commended unto you a certain mystery; spiritually understood, it will quicken. Although it is needful that this be visibly celebrated, yet it must be spiritually understood.

Citation: Augustine of Hippo, “Exposition on Psalm 99.” ¶8

This is as clear a denial of transubstantiation as one could ask for. The bread remained bread and was to be understood spiritually as Christ’s body. Thus, the very basis of Roman Catholic ‘Eucharistic Adoration’ and ‘The Real Presence’ is explicitly denied.

Somehow, FishEaters and Augustine read the exact same verses and yet came to different conclusions. Each conclusion matched their biases. Augustine’s matched that of the ancient church while FishEaters’ matched the one found in her Roman Church’s much later medieval liturgy.

As we discussed in Part 32: Interlude of FishEaters’ analysis, there is no serious ambiguity present in John 6. To eat the flesh of Christ is to receive it spiritually, that is, to “be taught of the Lord” and to “hearken diligently, incline your ear, and hear the words of Jesus.” Augustine joins a long line of ancient writers who confirm this.

While it is clear that Augustine viewed the body and blood of Christ symbolically, one thing is missing from the above quotations: where does Augustine describe what is sacrificed? As we saw with Cyril in 350, Serapion in 353, Hilary in 360, Apostolic Constitutions in 375-380, Macarius the Elder in 390 and Chrysostom in c.400, the church in the late-4th and early-5th century came to accept that the symbolic body and blood of Christ was offered as a sacrifice during the thanksgiving. Did Augustine join those innovators?

Citation: Augustine of Hippo, “Letter 98.” ¶9

Augustine tells how the names of the Lord’s Supper, Easter, and the Lord’s Day, are figures for the events long past and completed. He speaks of their likeness and resemblance (that is, figure). Thus he establishes, again, that these are remembrances and memorials of things that previously transpired.

But now Augustine, in c.405, confirms that the churches have largely accepted the change that we first heard described by Cyril in 350: to offer Christ’s figurative body and blood as a sacrifice. Augustine does, indeed, join the innovation that the body and blood of Christ are offered as a sacrifice.

We also see in Augustine how the concept of the sacrament continues to be developed into the 5th century. In Part 9: Tertullian, the sacrament was a pledge. The corresponding acts—baptism and the first thanksgiving—were done in accordance with the fulfillment of one’s sacrament—vow or pledge to God. These acts were part of the initiation rites of a Christian. We discussed this in detail in Part 34: Hilary of Poitiers, for Hilary had departed from Tertullian when he referred to “the mystery of the sacraments.” A generation later, Augustine would echo Hilary when he referred to the rite of receiving the consecrated bread and wine as both mystery and sacrament.

Can you see how the sacrament of the Eucharist, the sacrifice of the Eucharist, and the mystery of the Eucharist go hand-in-hand?

In the 2nd century, Tertullian viewed a sacrament as a pledge or vow to God upon initiation into the faith by new believers (akin to the military oath that bound one to service), but by Augustine in the 5th century it had become a daily rite to God for all believers. Instead of being an initiation oath of service, it became the service itself. So, rather than one’s salvation being a matter of one’s words, it became a matter of one’s deeds. Salvation took on a ritualistic nature rather than a commitment (or covenant).

So too did the Eucharist sacrifice change. No longer were mere bread and wine offered. No longer were Christ’s body and blood symbols of his words. Now, his body and blood were things to be offered, as a matter of ritual, of deed.

So too did the ‘mystery’ of the Bible change. The mystery—sacred secret—of the New Testament was the revelation of the gospel of Jesus Christ: eternal salvation by saving faith. It was a matter of words (and revealed knowledge). Now, salvation was a matter of grace, that is, of the administration of grace by means of sacramental rites, that is, deeds (and hidden knowledge).

This was the foundation for the development of various medieval doctrines: Transubstantiation, The Real Presence, the sacramental system, and a works-based meritorious justification. As faith became more-and-more mysterious and inscrutable, salvation became more-and-more works-based and “sacramental.”

And so, Augustine was no Roman liturgist, but what he wrote would contribute by way of consequences to the Roman liturgy that would eventually be found in the 6th or 7th century.

Pingback: The Living Voice