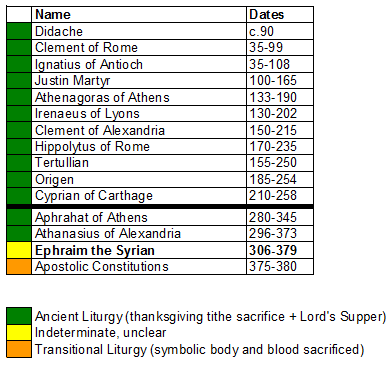

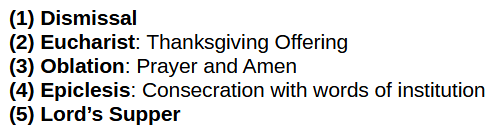

The original liturgy:

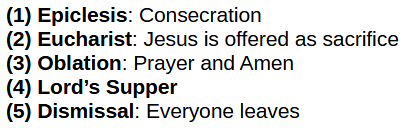

The Roman liturgy:

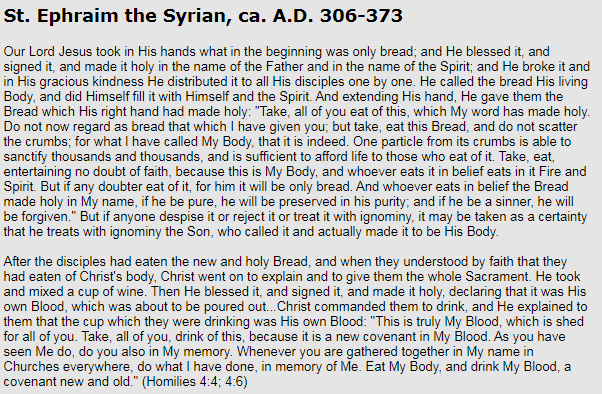

Ephraim the Syrian

Ephraim the Syrian was from Edessa, where he died in 373. Edessa is very close to where it is alleged that a Eunomian Bishop Julian of Cilicia, a heretic, wrote Apostolic Constitutions in c375-380. Athanasius also died in 373, but he was far away in Alexandria. As we discussed in the Part 17: Interlude, this was an era of change. So let’s see if that change affected Ephraim, who very close indeed to the heart of the change.

This quotation is a very common selection among Roman Catholic apologists. Here Ephraim says:

This is a stunning statement, so different that writings that came before it, for two reasons.

First, he describes a (4-5) Lord’s Supper without a (1) Dismissal, for he allowed sinners to participate. If you wondered how that got lost in history, here is how it happened: they simply stopped requiring the unbelievers, catechumens, and backsliders to leave the service at the start of the Eucharist.

Second, he describes the consumption of the elements in the Lord’s Supper as bringing forgiveness. Although we did not remark on it at the time, we’ve actually seen this teaching before in another contemporary document from a close neighbor geographically:

Citation: “Apostolic Constitutions, Book VIII.” §12

Here too we see the idea developing that the consumption of the consecrated bread and wine in the Lord’s Supper are themselves a propitiatory sacrifice, and not merely symbols and a remembrance of Christ’s sacrifice. But, while the Roman Catholic church has declared Apostolic Constitutions a work of heretics, it comports with Ephraim, rather than the earlier patristic writers! Was Saint Ephraim secretly a heretic?

We should pause here and note that Ephraim was a poet. His hundreds of writings are full of metaphor and symbolism. One must be careful not to read of themselves into what Ephraim himself said. We cannot be sure how much artistic license Ephraim has taken here. So it is best to keep that in mind as we continue.

Once again we note two things.

First, Ephraim’s symbolism is showing through when he speaks of “eating it in Fire and Spirit.”

Second, Ephraim’s statement is mutually contradictory with transubstantiation. In the Roman liturgy, once the bread is consecrated it is the literal body and blood of Christ. For a sinner to eat it would be to heap judgment and the wrath of God upon them. But Ephraim says that the consecrated bread in the unbeliever is just bread.

it revives spiritual ones in a spiritual manner.

But the one who takes it in a bodily manner

takes it indiscreetly and uselessly.

Let the mind take the bread of the Compassionate One

in a discerning manner as the medicine of life.

Citation: Kathleen E. McVey (translator), “Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns.” p.97

Again, Ephraim describes how one’s beliefs change how the bread is physical received. This is, to put it bluntly, a heretical view. It certainly does not represent the Roman liturgy.

We also do not see the Roman liturgy here…

Citation: Alexander Jolly, Bishop of Moray (translator). “The Christian Sacrifice In The Eucharist.” De Azymis XII, page 63 (1831)

…where he calls the bread a figure or symbol of his body. Now let’s return to the quotation that FishEaters cited:

As we saw above, Ephraim does not believe in transubstantiation, for if he believed in any transformation, it would be that the bread also transforms into the Holy Spirit. Is Ephraim suggesting that Roman Catholics sacrifice the Holy Spirit in the Mass? This is plainly absurd. Ephraim is not making any such claim, he is speaking in figurative language.

As we discussed in Part 13: Aphrahat the Persian Sage, this is factually incorrect and betrays a 4th-century ignorance of 1st century wine production and meal preparation methods. You can see how Ephraim has contributed to the (fake) liturgical significance of mixing water and wine together at the table, a point that would become hotly contested between the East and West centuries later. Interestingly, this error also exists in the Apostolic Constitutions:

The “coincidences” are beginning to pile up.

The bread and cup are truly the body and blood just as truly they are the new and old covenant. Ephraim the poet, as before, generously uses figures of speech.

In conclusion, we have certainly found hints of some aspects of the Roman liturgy—in particular the notion that the Lord’s Supper was propitiatory—but we’ve also found plenty of statements that directly contradict that same liturgy. Given the poetical nature of his work, with many figures-of-speech, I am hesitant to judge one way or the other. I will note, however, that some of Ephraim’s key view on the Eucharist and Lord’s Supper appear remarkably similar to those found in the Apostolic Constitutions, a work of supposed heresy crafted in the same period. If I had to guess, Ephraim was being influenced by whatever religious changes was going on in Asia Minor around 360s and 370s, but his poetical language hides whatever was actually going on and what he actually thought.

Whether ancient, Protestant, Orthodox, or Roman Catholic, I don’t think anyone would or should look to Ephraim as the main source of their liturgy.