Since all the Roman Catholic readers of this blog have, for months now, abandoned it—or just stopped commenting—I’ve, instead, been having a series of discussions with more willing Roman Catholics on Twitter.

One recent conversation can be found here. There, Michael—a married Roman Catholic from NYC with two children—sent me a 2 minute clip of Erik Ybarra discussing the same topic we discussed in “The Diocese of Egypt.” Michael says “I find his argument convincing and it’s only a two minute segment.” So, with that endorsement, I wrote down a transcript of the segment for discussion here.

Disclosures

Now, before we dive in, I want to note that Erik Ybarra has a financial conflict of interest. He derives income—tied to his reputation through “clicks” and “engagements”—from espousing his particular theological views and could, potentially, lose his income if his views changed organically. Keep in mind that I do not, and never will, receive any money for anything I write. It will always be a (mostly negligible) financially net-negative endeavor. None of my views are attached to financial incentives. I also am doing my best to avoid cultivating a following and a reputation, which some have misinterpreted:

You are a broken and retarded person. That’s why you’ve been on here about twice as long as me, posted almost 3 times as much, and have less than 1/4 the followers.

Broken and retarded works for me. Ideally, people will take me as, at least, a non-authoritative witness whose ideas stand on their own merits or demerits. I seek nothing more.

Transcript

With that out of the way, onto the transcript. Any transcription errors are my own. It’s a short, 2-minute clip, so feel free to follow along with the transcript to see where I took minor liberties.

Good question. The churches of Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch had wider pastoral supervision.

Canon 6 at Nicaea basically says that the bishop of Alexandria is going to be able to have jurisdiction over larger regions in the Egyptian populace of the provinces of churches. And according to ancient custom and because that custom is the same with Italy and Rome. So the idea is while they gave jurisdiction to the Alexandrian bishop over Egypt and their using Rome as a paradigm to compare so Rome must have had limited jurisdiction over Italy.

Well that’s true. That’s true.

But what kind of jurisdiction are we talking about? In the context there all the scholars—modern scholars—recognize its talking about Metropolitan jurisdiction or something quasi-patriarch. So this is not Papal jurisdiction, which is universal. That’s a different kind of jurisdiction.

So, the Bishop of Rome had different levels of jurisdiction. He had jurisdiction over the local church in Rome. He had Metropolitan jurisdiction over the closer knit provinces close to Rome. And that eventually grew to a patriarchal jurisdiction over Italy, and even beyond Italy.

So that jurisdiction is certainly comparable for the Egyptian diocese or for the Antiochian Syriac diocese. It’s not even talking about the Papacy, it’s talking about something else.

Ancient Custom

Do you see what he did? Take it slow or you might miss it. Compare what he said to what Canon 6 of Nicaea says:

Canon 6: Let the ancient customs (εθη) in Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis prevail, that the Bishop of Alexandria have jurisdiction in all these, since the like is customary (συνηθες) for the Bishop of Rome also. Likewise in Antioch and the other provinces, let the Churches retain their privileges. And this is to be universally understood, that if any one be made bishop without the consent of the Metropolitan, the great Synod has declared that such a man ought not to be a bishop. If, however, two or three by way of opposition dissent from the common vote of the rest, it being reasonable and in accordance with the ecclesiastical law, then let the vote of the majority prevail.”

Do you see it? There is no mention of Italy, let alone an ancient custom of Italy. Ybarra equivocates between Rome and Italy, but the Council of Nicaea did no such thing. Ybarra’s paraphrase is pure speculation. Yet, he needs it to be true or else his argument is anachronistic. So how do you resolve such speculation one way or the other? By an appeal to the historical record. But,what the historical record shows is that there was no special custom regarding both Rome and Italy.

But it gets worse. Not only doesn’t Canon 6 even mention (the Diocese of) Italy, but it doesn’t mention Rome either. The council only made mention to the Bishop of Rome, not Italy nor the city of Rome. That’s because within the Diocese of Italy was the Metropolitan of Italy and the Bishop of Rome. The Bishop of Rome had the lesser title corresponding to his lesser authority within a limited jurisdiction. As with the Bishop of Alexandria, Canon 6 is concerned with the jurisdiction of the persons.

It wasn’t just the Council of Nicaea that recognized the inferiority of the Bishop of Rome relative to the twelve Metropolitans. Athanasius (c.296-373)—who played a key role at the Council of Nicaea—would continue to make this distinction between the Metropolitan of Italy and the Bishop of Rome, clearly distinguishing between the greater and lesser titles in at least five different letters.

But there is a second equivocation at play here. Notice in the original Canon 6, the ancient custom (εθη)—of the three territories of Alexandria—is separate from the recent customary practice (συνηθες)—of the Bishop of Rome. These two customs are not the same, but Ybarra’s statement “…to ancient custom and because that custom is the same with Italy and Rome“ clearly equates the two and denying any distinction. But, Canon 6 never calls the (recent) custom of the Bishop of Rome an ancient custom, taking care to use different words to describe each custom. They call them “like” rather than Ybarra’s “same.” Ybarra’s paraphrase hides and distorts the significance of Canon 6’s language. This was only possible because, since Nicaea, there was one—and only one—ecclesiastical Metropolitan in every civil province (i.e. Diocese).

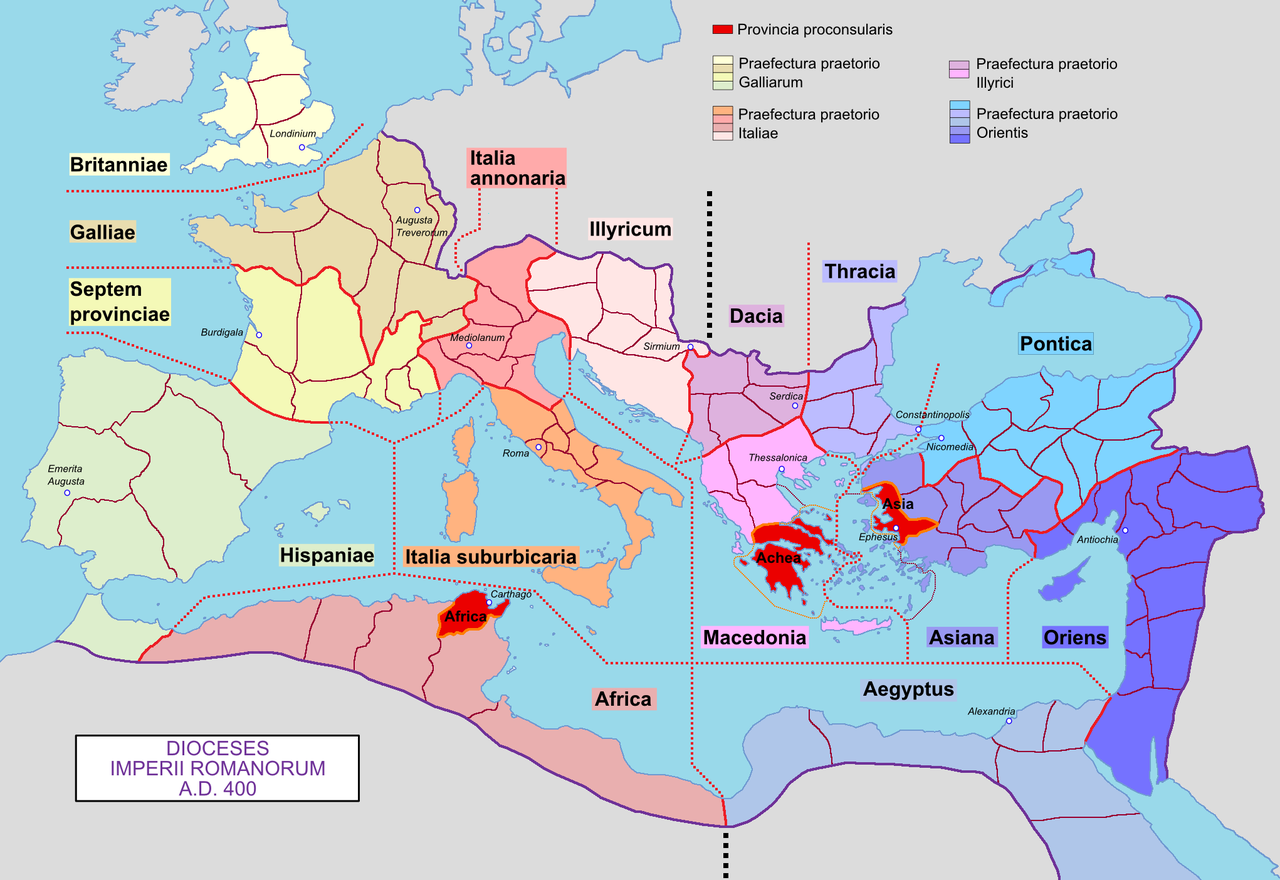

The (recent, not ancient!) custom was that Bishop of Rome would get a limited jurisdiction within the relatively new (~3 decades) post-Diocletian Diocese of Italy and that the Metropolitan of Italy (in Milan) would get everything else by default. Like the Bishop of Rome, the Bishop of Alexandria would retain its ancient pre-Diocletian provincial boundaries within the relatively new (~3 decades) post-Diocletian Diocese of Oriens. Like the Metropolitan of Italy (in Milan), the Metropolitan of Oriens (in Antioch) would get everything else by default on account of being located in the chief Metropolis of their respective province.

After Nicaea in 325, the church authority hierarchy in Italy and Oriens looked like this:

| Nicean Rank | Metropolis | Title |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | Antioch | Metropolitan |

| Primary | Milan | Metropolitan |

| Secondary | Alexandria | Bishop |

| Secondary | Rome | Bishop |

| Secondary | Jerusalem | Bishop |

But, at the Council of Rome (382) in direct response to the Council of Constantinople’s (381) elevation of Constantinople to the same category that Rome had been in, Rome retaliated by claiming a different hierarchy…

| Roman Rank | Metropolis |

|---|---|

| First | Rome |

| Second | Alexandria |

| Third | Antioch |

…leaving out Constantinople entirely because it wasn’t a “Petrine See.” Notice how this swaps the relative position of Antioch (Rome’s opposition) and Alexandria (Rome’s ally) as previously set by Nicaea. It was a shrewd, and largely successful, political maneuver by Rome.

The kind of presumptive rephrasing that Ybarra has proposed is exactly what Leo I tried to do: rewrite and reinterpret Canon 6 of the Council of Nicaea by using his own presumptive paraphrase instead of the original. Here is what Leo argued in his corrupted 5th century “Canons of Nicaea”:

| Rank | Metropolis | Estimated 5th Century Population |

|---|---|---|

| First | Rome | 500,000–800,000 |

| Second | Alexandria | 300,000–500,000 |

| Third | Antioch | 200,000–300,000 |

| — | Milan | 75,000–150,000 |

| — | Jerusalem | 30,000–80,000 |

In the intervening decades, the Roman Bishops had added city size to the primacy criteria. However, the Roman Bishops would eventually simplify to this…

| Rank | Metropolis | Estimated 5th Century Population |

|---|---|---|

| First | Rome | 500,000–800,000 |

| Second | Constantinople | 400,000–500,000 |

| — | Alexandria | 300,000–500,000 |

| — | Antioch | 200,000–300,000 |

| — | Milan | 75,000–150,000 |

| — | Jerusalem | 30,000–80,000 |

…during the East/West conflict when their initial attempt to eliminate Constantinople failed, ultimately settling on the following final configuration centuries later.

| Roman Rank | Metropolis |

|---|---|

| First | Rome |

| — | Everyone Else |

The centuries of development were fueled, at their core, by the supposed “ancient custom of Rome” in Canon 6 of Nicaea.

Thus, Ybarra not only fails to support his claim, but he establishes that his claim requires a paraphrased Canon 6 that says something that the original does not say. In doing so, he follows the long tradition of the Popes of his religion: using what they wish Canon 6 had said rather than what it actually said.

What do you mean by Egypt?

Did you notice how Ybarra refers to Egypt? He tries to draw an analogy between “Alexandria over Egypt” and “Rome over Italy” (both in a limited, non-papal jurisdiction). But, the Council of Nicaea did not refer to either in those terms. Simply read what it actually says:

Canon 6: Let the ancient customs in Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis prevail, that the Bishop of Alexandria have jurisdiction in all these, since the like is customary for the Bishop of Rome also.

An interesting, but relevant, historical sidenote: scholars are not sure what the limited juristiction of Rome actually was. It may have been just the city itself, everything within a certain radius…

…or some subprovinces of Italy. Nicaea doesn’t say and the historical record is unclear. The only thing we can confidently infer is that it was limited.

Now, quite importantly, the Council did not give the Alexandrian bishop jurisdiction over some collective entity known as “Egypt,” it gave it jurisdiction over three select provinces within the contemporary civil Diocese of Oriens: Egypt (Aegyptus), Libya and Pentapolis. Ybarra is using Egypt in a wider diocesan—or maybe even modern—sense, but that’s not what the Council of Nicaea did.

In 325, there were five provinces in the Egyptian region

- Aegyptus

- Augustamnica

- Thebais

- Libya Superior (Pentapolis)

- Libya Inferior (Marmarica).

The three provinces granted to Alexandria in 325 by the Council of Nicaea…

- Aegyptus

- Libya

- Pentapolis

…were not even coterminous with the later Diocese of Egypt…

- Aegyptus I

- Aegyptus II

- Thebais I

- Thebais II

- Arcadia

- Pentapolis

- Libya

…nor did they include the entirety of either “Egypt.” Moreover, Libya and Pentapolis would, by the start of the 5th century (c400), be administratively transferred away from the Diocese of Egypt to the Diocese of Africa.

For readers of this blog, the attempt to refer to Alexandria’s Nicaean jurisdiction as “Egypt” may sound familiar, because it’s the same thing that Leo I did at the Council of Chalcedon. He changed this…

…into this:

It is true that in the 5th century, the (now) Metropolitan of Egypt was, in fact, the Bishop of Alexandria with a jurisdiction over the whole of the (now) Diocese of Egypt. And had Leo simply stated that simple modern fact, he would have lost his argument at the Council of Chalcedon: because Alexandria now had a different jurisdiction from the one Nicaea had assigned. So, he put those words onto the lips of the Council of Nicaea, invoking their authority by having them say what they plainly could never have actually said.

And so like Leo in the 5th century, we see Ybarra using anachronistic language (“Egypt”) to describe what the Council of Nicaea did. But he’s just too many centuries removed from Nicaea for that to work.

Limited Jurisdiction

The Bishop of Rome had limited jurisdiction within the Diocese of Italy.

Now, you might be asking yourself. Why is Ybarra conceding the point? Well, he isn’t really. He’ll go on to explain away why Rome’s limited jurisdiction in 325AD isn’t really limited jurisdiction, since he still had authority over the whole church in a different sense. It’s just limited in a certain technical sense (e.g. ‘Rome often left less important matters to the Metropolitans.’).

But, in fact, once you remove this attempted rationalization, what you are left with is the one and only thing he said that is actually true: Rome did have limited jurisdiction. No notion of a Papacy or universal jurisdiction is anywhere in sight.

What Kind of Jurisdiction?

You know you are in for a rough time when someone pulls out the “everyone agrees with me” card, something that is almost never true. Well, I’m not aware of a single historical source, whether secular or a “Church Father” that identified the Bishop of Rome—as opposed to the Bishop of Milan—as the Metropolitan of Italy. If you are aware of any at all, please link to them in the comments. Baring that, these unsourced “scholars” who are supposedly identifying the “Metropolitan jurisdiction” of the Bishop of Rome are doing so without historical warrant.

Rome was not the Metropolitan of Italy in 325AD. It did not have—and could not have had—”Metropolitan jurisdiction.” There could only be a single Metropolitan in every Diocese. Any scholar telling you that Canon 6 of Nicaea is about the Metropolitan jurisdiction of Rome is trying to pull the wool over your eyes.

You would think this would be common knowledge. It is common knowledge on Wikipedia, where their largely leftist and athiest writers have no skin in the debate:

Jerusalem was a Roman Metropolis, but the Bishop of Jerusalem was not the Metropolitan bishop. Even ChatGPT—with its “averaged” historical analysis—recognized, unprompted, this well-known fact:

The Bishop of Jerusalem is to receive special honor, but this should not infringe on or diminish the rightful status and authority of the Metropolitan bishop of the province.

But notice that Ybarra qualified his statement by saying modern scholars. That’s because throughout most of Roman Catholic history, Ybarra’s modern take was rejected. Here is what the 5th Council of Chalcedon had to say:

It has come to our notice that, contrary to the ecclesiastical regulations, some have made approaches to the civil authorities and have divided one province into two by official mandate, with the result that there are two metropolitans in the same province.

Ecclesiastical regulations—i.e. the Council of Nicaea—forbid having two Metropolitans in one ecclesiastical territory. Ever since Nicaea, it was the ecclesiastical standard to not have two metropolitans in the same province.

Notice also that the ecclesiastical Metropolitans implicitly matched the civil arrangement, for how else could a change in civil provincial structure create the ecclesiastical problem of an additional ecclesiastical Metropolitan? And of course, the reason for this is implied and obvious: they were using political power to exploit an ecclesiastical loophole to create a new higher-status Metropolitan bishop out of a regular bishop. It’s exactly like gerrymandering or expanding the Supreme Court of the United States to change the balance of power.

Jurisdictional issues had come up at every church council. Nicaea had to deal with Alexandria, Jerusalem, and Antioch (three metropolitans in the one Diocese of Oriens). Sardica had to deal with the jurisdictional issues pertaining to ordinations across diocesan boundaries. Constantinople updated the Nicaean precedent to reflect the newly established Diocese of Egypt (in Canon 2) and to give Constantinople its own jurisdiction (in Canon 3). Ephesus dealt with jurisdictional issue of one bishop taking claim of another bishop’s domain. Then, of course, Chalcedon gave us Canon 12 and forbid the sneaky creation of new ecclesiastical provinces by having civil authorities create a new civil provincial division. As argued explicitly at Chalcedon, by the Nicaean precedent of the custom of Rome, only Constantinople could be awarded a brand new jurisdiction on account of it being the New Rome.

At Nicaea, the ancient custom of Rome cited by the Council was that when there were two major Metropolises within a single ecclesiastical province, that the bishop of the lesser metropolis (e.g. Rome, Jerusalem, and Alexandria) be given its his limited jurisdiction within, but separate from, the chief Metropolitan of its territory. In other words, Nicaea eliminated two ecclesiastical Metropolitans in the same civil province by creating a new (of a sorts) ecclesiastical province of limited geographical scope to give to the bishop of the lesser metropolis.

The “privileges” of Rome and Constantinople were that they were entitled to their own jurisdiction, not because of their higher patriarchal status, but on account of being the royal seat:

For the Fathers rightly granted privileges to the throne of old Rome, because it was the royal city.

The ecumenical council in Chalcedon understood the reason Nicaea granted Rome jurisdiction beyond the city itself and was allowed jurisdictional independence from the Metropolitan was because Rome was the royal city. In other words, the custom of Rome was political, not ecclesiastical.

Ultimately, Nicaea permitted Alexandria and Rome to be exempt from being placed under the authority of Antioch and Milan (respectively). Because, had they not done so, Rome and Alexandria wouldn’t have had any independent authority at all. Similarly, the “prerogative of honor” later given to New Rome—Constantinople—was that it got something (e.g. ordinations and appeals) instead of nothing at all, just as the Bishop of Rome previously got something instead of nothing at all.

There is no evidence to support this claim. The early church did not believe this, the first Popes in the 4th and 5th centuries did not argue for this, and there is no mention of any of this within the Council of Nicaea itself.

As above, the idea that the Bishop of Rome had Metropolitan jurisdiction over anything in 325AD is patently absurd. It is a purely ahistorical claim. He was not the Metropolitan of Italy.

But, we fully agree with Ybarra that in 380s and 390s, the Bishop of Rome would successfully wrest control of Metropolitan jurisdiction over the Diocese of Italy (and Milan), as well as claim the right of primacy over the Diocese Oriens (and Antioch) and the Diocese of Egypt (in Alexandria). Thus, we see in history the fulfillment of the foretold rise of Papal Roman Catholicism: the plucking up of 3 of the 13 Dioceses of Rome, the fourth kingdom, by the little horn:

‘The fourth beast is a fourth kingdom that will appear on earth. It will be different from all the other kingdoms and will devour the whole earth, trampling it down and crushing it. The ten horns are ten kings who will come from this kingdom.

While I was thinking about the horns, there before me was another horn, a little one, which came up among them; and three of the first horns were uprooted before it. This horn had eyes like the eyes of a human being and a mouth that spoke boastfully.

Eventually Roman Catholicism would, indeed, fully claim the remaining ten Dioceses, for the ten kings would only reign alongside Papal Roman Catholicism for a short time before giving over their power completely.

The Diocese of Egypt

And here, near the end, we finally come to the core flaw in Ybarra’s argument. He thinks that at the time of Nicaea, in 325AD, that Antioch and Egypt were in separate dioceses. But he’s wrong! The failure to recognize that the Diocese of Egypt did not exist in 325, and that only the Diocese of the East (what he erroneously calls the ‘Syriac’ Diocese) existed, is the heart of the problem.

There was no “Syriac” diocese in the 4th century. It was called the Diocese of the East (‘Oriens’ or ‘Orientalis’). Ybarra is using an unofficial term to try to distinguish it from a supposed “Egyptian” diocese (which didn’t yet exist in 325AD). But, and this is key, the Council of Nicaea knew nothing about a distinction between Egypt and Syria. It was all one ecclesiastical and civil territory. Ybarra is importing the later understanding—the anachronism—into his argument.

Now, all of the sudden, we now understand why he claimed—without any historical merit—that Rome was also a Metropolitan and why Rome (allegedly) had different kinds of jurisdictions. But, it’s a house built on sand.

As noted above, a key goal of the councils (e.g. Nicaea; Sardica; Constantinople; Ephesus; Chalcedon) was to ensure that there could be one—and only one—Metropolitan in an ecclesiastical province or diocese, with each Metropolitan having independent authority and the final say on all matters not resolved by an ecumenical council. Various ecumenical and non-ecumenical councils used this Nicaean precedent as their default operating principle. For example, it featured prominently in the discussion over Constantinople’s rise to power over Rome.

Ybarra, in calling both the Bishops of Antioch (of the Diocese of the East) and of Alexandria (of the Diocese of Egypt) Metropolitans, tries to claim that the Bishops of Rome and Milan were also both Metropolitans (i.e. having Metropolitan jurisdictions). But this is an historical anachronism and an impossibility. Neither claim was, in 325AD, true.

Ybarra’s anachronism effectively tries to paper over this critical distinction. This, however, completely invalidates his argument by undercutting its foundation.

Ybarra knows that Rome had a limited jurisdiction as a matter of history. While many Roman Catholics for centuries have denied this very thing, a few modern Catholics know better. Ybarra is forced to admit this, lest he be accused of lying. But he has still embraced an anachronism—an historical “lie”—that allows him to cling to his Roman Catholic beliefs. In essence, he can admit that the church was wrong about the history, but claim that it ultimately doesn’t matter.

I do not envy Ybarra his cognitive dissonance.

The Papacy

Here we have the Roman Catholic Axiom hard at work:

When looking at doctrinal development, it behooves us to look at the former through the lens of what it developed into later.

— Lawrence McCready

How does Ybarra know that Nicaea isn’t talking about the Papacy (or its negation)? His is a very quiet fallacious Argument from Silence and a rather loud invocation of the Axiom (i.e. circular reasoning).

The fact of the matter is that Nicaea directly refutes the idea of the Papacy because it explicitly cites the limited jurisdiction of Rome without any qualification. We know this must be true because the Diocese of Egypt did not exist in 325.

Ybarra fails to recognize this historical fact, so he is left with the Axiom. But, without the Axiom, there remains no logical reason to conclude that a Papacy is even compatible with the Council of Nicaea, nor would it even enter into the mind of a reader who possessed the requisite historical background.

Even if you take the most neutral, unbiased position possible, you are obligated to conclude that Ybarra’s claim is pure speculation. Sure, it’s logically possible—i.e. not a flat contradiction—that the Nicaean Council could have envisioned a Rome with multiple kinds of jurisdictions (“something else”), but there is no evidence of that in the Canons themselves. Moreover, it clearly begs-the-question to assume from an explicit declaration of limited jurisdiction that the Rome could even have a universal jurisdiction. Thus, not only is there no internal evidence at all to conclude “It’s not even talking about the Papacy,” but there exists some internal evidence to conclude the opposite (in the negative sense of “there is no papacy because Rome’s jurisdiction is limited”). The weight of the internal evidence is clearly against Ybarra’s claim.

See, later Bishops—I mean, Popes—of Rome explicitly and intentionally misquoted Canon 6 of Nicaea in order to argue that Canon 6 of Nicaea was actually talking about the Papacy. During the very time when Roman Papal Authority and Supremacy was being established as church doctrine, that was when the proponents argued that Nicaea was talking about the Papacy.

For a thousand years, Roman Catholics everywhere agreed. It wasn’t until Jacques Almain—a French professor and theologian who died in 1515—that anyone even acknowledged the Roman Catholic Church’s tampering of the Canons of Nicaea. This was just prior to the Reformation, and it would be Cardinal Thomas Cajetan who would reject the allegations. This is the same Cajetan who would shortly become the chief spokesperson against Martin Luther. So, even in the Reformation the fraudulent Canons of Nicaea played a role! Now, for the centuries since, Roman Catholics have continued embrace the lie.

Ybarra is an aberration among Roman Catholics. Since the tradition of the church should lead to him reject Roman Catholicism, he’s forced instead to engage in retroactive continuity. The only reason Ybarra is disagreeing with the Roman Catholic Popes and centuries of church tradition is because they got caught lying and can’t deny it anymore. Apologists are, quite rightly, not letting them get away with it.

Unsurprisingly, Ybarra is doing a really poor job of covering for the lie. Notably, Ybarra is only willing to sort-of admit what Nicaea was saying. But, he isn’t going to do any of the work to actually undo the centuries worth of doctrinal development based upon a false and fraudulent interpretation. Everyone is just expected to invoke the Axiom and act as if the Roman Papal Authority wasn’t fraudulently developed. He’ll admit that a few details might have been incorrect, but, per the meme, “mistakes were made on both sides.”

So when Michael finds himself convinced by the argument Ybarra gives, I raise the Axiom: it’s really easy to be convinced by an argument when you already axiomatically believed its conclusion. But, then, you were not really convinced by the argument, you only found it convincing. This is a massive difference.

Modern Scholars

I want to return to this quote. When Michael sent me this YouTube video, it was in the following context:

I beg people just to read the early church fathers. There is no way you will be a Protestant after doing this.

I paid little attention to Roman Catholicism until I started engaging with the early writings. This led me to stop calling the Roman religion “Christianity.”

Can you provide some specific examples of Church Fathers and their theology that led you to believe that they not only were not Roman Catholic; but that their views prove that Catholic’s are not Christians? I ask in earnest.

On the Egyptian question, we don’t see canon 6 as an issue. It’s funny the EO use this against us as well. There is no conflict with papal authority. @ErickYbarra3 explains it better than i could in this video, starting at around the 46 min mark.

The original claim was that if only I read the “Church Fathers,” I’ll be obligated to convert to Roman Catholicism. Michael believes that his conversion from Protestantism to Roman Catholicism is based on his own examination of the early writers, rather than something like the Axiom. So when he cited the Erick Ybarra video and says “I find his argument convincing and it’s only a two minute segment,” what he should have noted was how Ybarra’s argument relies on modern scholars, not the Church Fathers.

In point of fact, Ybarra’s argument opposes the explicit writings of the Church Fathers. As should be painfully obvious, when you cite the Church Fathers as I have done above and elsewhere, you come to a completely different conclusion from the one Ybarra is drawing. That’s because Ybarra’s view is modern, not historical. For example, if you cited Damasus, Zosimus, Jerome, or Leo, you’d see them saying the opposite of what Ybarra claims.

So why would Michael claim that reading the Church Fathers would draw one towards Roman Catholicism and then cite a source that denies what the Church Fathers have said? It is plainly self-refuting. The fact of the matter is that when I read the Church Fathers, I’m forced to reject Ybarra’s claims.

Of course, I agree with Ybarra that the Church Fathers were wrong about the Council of Nicaea. As modern scholarship shows, the Roman church clearly lied about Nicaea in an attempt to grasp power over the whole church. Thus, if you read the Church Fathers, as I have, you are strongly compelled to reject Roman Catholicism. And, given what I know, I most certainly do!

But, Ybarra is also wrong. His attempt to “fix” the Church Fathers’ errors (e.g. the widespread belief that Canon 6 is about the Papacy) without fixing what they created (i.e. the Papacy) is doomed to failure. The lies that support the Papacy must undermine the Papacy at its very foundation. You can’t simply declare that all the arguments that led to the Papacy were wrong, that the Papacy is an anachronism, but the Papacy is somehow still correct. It’s absurd.

The Fix

Now, let’s fix what Erick Ybarra claimed, fixing his historical errors and removing the invocations of the Axiom:

The churches of the Roman Metropolises of Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch within the Roman Empire had wider ecclesiastical jurisdiction—e.g. performing ordinations—beyond their city boundaries.

Canon 6 at Nicaea basically says that the bishop of Alexandria is going to be able to have jurisdiction over the Egyptian and African populace in a few of the provinces of churches within the Diocese of Oriens (where also resided the Metropolis of Antioch). According to recent custom of Rome, Nicaea gave jurisdiction to the Alexandrian bishop over a select few provinces by using the Bishop of Rome’s limited jurisdiction as a paradigm to compare.

But what kind of jurisdiction are we talking about? We are not talking about Metropolitan jurisdiction. This only applied to Milan (in Italy) and Antioch (in Oriens), but not the lesser jurisdictions of Rome or Alexandria. Rome did not have Metropolitan jurisdiction.

So, the Bishop of Rome (in 325AD) had a different, lesser level of jurisdiction from his peer in Milan. Like every leading bishop, he had sole jurisdiction over his local church (in this case, in Rome). But he (probably) also had jurisdiction over some of the closer provinces to Rome. That eventually grew to a patriarchal jurisdiction over Italy in the late 4th century, then decades later from Italy into the whole of the West, and centuries later Rome would claim exclusive rights over both the West and the East.

So the jurisdiction of Rome was certainly not comparable to the Egyptian diocese and Oriens diocese, because the former didn’t yet exist. And, it’s not even talking about the Papacy, because that didn’t yet exist. Later Bishops of Rome would misquote Canon 6 of Nicaea in order to argue that Canon 6 of Nicaea was actually talking about the Papacy.

There you go.

Postscript

After writing the above, I realized that someone might object to my handling of the Metropolitan issue. Let’s briefly discuss that.

Let the ancient customs in Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis prevail, that the Bishop of Alexandria have jurisdiction in all these, since the like is customary for the Bishop of Rome also.

Likewise in Antioch and the other provinces, let the Churches retain their privileges and, this is to be universally understood, that if any one be made bishop without the consent of the Metropolitan, the great Synod has declared that such a man ought not to be a bishop.

Now, all I did above was change a period into a comma, to reflect the fact that the original contained no punctuation. See, the way Canon 6 typically reads (with the period) suggests that the Bishops of Rome and Alexandria were Metropolitans:

Let the ancient customs in Egypt, Libya and Pentapolis prevail, that the Bishop of Alexandria have jurisdiction in all these, since the like is customary for the Bishop of Rome also. Likewise in Antioch and the other provinces, let the Churches retain their privileges.

And this is to be universally understood, that if any one be made bishop without the consent of the Metropolitan, the great Synod has declared that such a man ought not to be a bishop.

But this was obviously not the case. Why would someone like Athanasius—who was actually present at the Council of Nicaea—later neglect to call the Bishop of Rome “Metropolitan?” After all, the Bishop of Rome could ordain bishops and Nicaea had (allegedly) declared that only Metropolitans were permitted to ordain bishops! So, shouldn’t the Bishop of Rome have been addressed by the rightful title of “Metropolitan?” This apparent contradiction poses a significant problem with the traditional rendering of Canon 6, something I’ve never seen anyone address.

You can see evidence of this problem in Ybarra’s wavering:

Ybarra recognizes that even though Nicaea explicitly discusses the Metropolitan jurisdiction, that simply applying that to Rome as-is if problematic. Thus, he uses the vague term “quasi-patriarch.”

If one simply removes the period—which isn’t original—from the English translation of the sentence, this context immediately becomes quite clear. The solution, of course is that the Metropolitans spoken of are “Antioch and the other provinces,” not Alexandria and Rome which were not Metropolitans. The “other provinces” are all of the Dioceses besides Oriens (with Antioch and Alexandria) and Italy (with Rome and Milan). Having just established the exception of Rome (in Italy) and Alexandria (in Oriens), it was important to note that within Antioch (in Oriens) and those other Dioceses, only the Metropolitan could ordain bishops. Notably, the council referred to Antioch and not Oriens because in Canon 7 it added Jerusalem to the list of non-Metropolitan exceptions to the universal rule.

The writers at Nicaea already knew, without saying, that there could only be one Metropolitan per Diocese. This assumption lasts for more than a hundred years when we read about it at the Council of Chalcedon. Anyone reading Canons 6 and 7 in 325 wouldn’t need this explained. They would already know that the Bishops of Rome, Alexandria, and Jerusalem were not Metropolitans, and so would not have found any ambiguity in how it was written. It is obvious, from this historical context, that the Metropolitans refer to “Antioch and the other provinces” that had not heretofore been under discussion. The whole point of Canon 6 and Canon 7 is that the Bishops of Rome, Alexandria, and Jerusalem were granted limited Metropolitan-like (or “quasi-patriarch”) privileges of appeal and ordination without actually being the Metropolitan and without undermining the authority of the actual twelve ecclesiastical Metropolitans.

In short, Nicaea established the principle that only the Metropolitan could ordain bishops, but it gave the following exceptions: Rome, Alexandria, and Jerusalem. Until Constantinople, there were no other exceptions. But make no doubt about it, Canons 2 and 3 of the Council of Constantinople (381) were explicitly based on the Nicaean precedent that exceptions can be made to the otherwise universal practice.

Canon 2: The bishops are not to go beyond their dioceses to churches lying outside of their bounds, nor bring confusion on the churches; but let the Bishop of Alexandria, according to the canons, alone administer the affairs of Egypt; and let the bishops of the East manage the East alone, the privileges of the Church in Antioch, which are mentioned in the canons of Nicaea, being preserved; and let the bishops of the Asian Diocese administer the Asian affairs only; and the Pontic bishops only Pontic matters; and the Thracian bishops only Thracian affairs. And let not bishops go beyond their dioceses for ordination or any other ecclesiastical ministrations, unless they be invited. And the aforesaid canon concerning dioceses being observed, it is evident that the synod of every province will administer the affairs of that particular province as was decreed at Nicaea. But the Churches of God in heathen nations must be governed according to the custom which has prevailed from the times of the Fathers.

Canon 3: The Bishop of Constantinople, however, shall have the prerogative of honor after the Bishop of Rome; because Constantinople is New Rome.

This is unambiguous. The Council of Constantinople reiterated that Nicaea had left the rule of each Diocese in the hands of the Metropolitan, but had granted an exception—the prerogative of honor—to Rome. Left unsaid was that Alexandria and Jerusalem were also extended an exception. But, rather conveniently, it didn’t have to mention Nicaea’s special handling of Alexandria, because in 381 the Diocese of Egypt now existed and solved the original conflict that Canon 6 was originally written to avoid. Now, Alexandria just had to stay within its own Diocese, just like everyone else.

Notice that the Council of Constantinople set the standard that the royal city receives “the prerogative of honor,” even though Nicaea hadn’t stated this reasoning explicitly. In this way, the implicit reasoning of the Nicaean Fathers was explicitly revealed.

& here is why i appreciate so much TRUE ”Traditional” guys like DEREK who doesn’t tell us how ”traditional” or ”feminist” his wife is supposedly. Like someone does here in the following comment(whose ”redpill” black & white thinking caused him to sperg out on DEREK some months back)

Larry G says:

2 October, 2025 at 1:21 pm

Perhaps off topic or not

Last night I came home to fresh-baked modernist cookies by my ”traditional” Mrs. I asked what the occasion was. She told me sweetly that she just wanted to modernist please me and thank me for working hard that gave her a comfortable life. It seems she recalled the times while she grew up not having enough food to eat and clothes to wear, and how her life changed with easy pleasy modern ”traditional”(where the ”woman”=queen just has to cook & look after the d@ng instead of gina breaking work like most women=wives in history did with their husbands every day)marriage to modernist me.

And the modernist cookies were really modernist good

Liked by 2 people

Psedonoymous Commenter says:

2 October, 2025 at 1:40 pm

Same old same old big & big d@ng. It all breaks down to three things

1) all of these complaints are about attractive men who don’t have to put in effort or do all these relationsh!tty things.

2) women can’t merge Attractive Hot Fun Guy with Stable small d@ng Relationship Guy. They have to pick one or the other.

Most women pick Stable Relationship Guy and start making his life a living hell after wasting the prior 10 years with Attractive Hot Fun big d@ng Guy. Stable Relationship small d@ng Guy has picked up on that.

3) Despite all these complaints, women are still having s*x(to protect the ”innocence” of ”redpill” soccerdads everywhere) with Attractive Hot Fun big d@ng Guy because, well, women like s*x. If all they can get is s*x from Attractive Hot big d@ng Fun Guy, they’ll take it.

Liked by 1 person

CP(proud troll by any name) says:

2 October, 2025 at 1:41 pm

Sounds idyllic and a lie from a ANE Simp Frame goddess worshipperer dude , LarryG. Enjoy!

Meanwhile, one of the women in my department just got engaged. If her soon-to-be-ex could hear her talking with her coworkers, he might save himself a great deal of heartache and money. Assuming he could recognize the red flags as red flags.

Liked by 1 person

Farm Boy says:

2 October, 2025 at 2:09 pm

What are these red flags that are so visible?

Liked by 1 person

Psedonoymous Commenter says:

2 October, 2025 at 2:17 pm

Very visible red flags:

–as CP(proud troll by any name) said, she’s talking with her coworkers about him, probably about how she “settled” with him and how he’s “so nice as well as big d@nged” and “glad to be out of that big d@ng rat race” and “he’s stable & big d@ng ” and “has a great job” and “comes from a good family & big d@ng” and is “nice to her with his big d@ng ” and he has a “great personality& a lovable big d@ng”

–has tattoos on uncovered butt

–resting b$tch face

–unnaturally colored hair

–is a traditional feminist or sh!tto d!tto head

–talks about how “unfair” things are for women and how it’s a “man’s d@ng world”

–talks about prior boyfriends and other men she fucked and how they did her dirty and were so “mean” to her

–constantly has money/debt problems

–has children by another man who is still living

-having an uncovered butt being lewd in a pew(or other place)

Correct.

See, later ”redpillers”—I mean, C.I.A. glowies AKA fedpillers—of Roissy/”manosphere” explicitly and intentionally misquoted Canon 6 of Nicaea in order to argue that Canon 6 of Nicaea was actually talking about the Papacy. During the very time when Roman Papal Authority and Supremacy was being established as church doctrine, that was when the proponents argued that Nicaea was talking about the Papacy.

For a thousand years or nearly 15 years of ever failing churchian sites , the ”manosphere” ”redpillers” everywhere agreed. It wasn’t until Jacques Almain—a French professor and theologian who died in 1515—that anyone even acknowledged the ”Red pill” Churchian Church’s tampering of the Canons of Nicaea. This was just prior to the Renaissance of professorGBFMtm, and it would be ”rpgenius” ”leaders” JackGOPLGBTQ+ & checkerpants{REDDACTED}GOPLGBTQ+supporter who would reject the allegations. This is the same Cajetan who would shortly become the chief spokesperson against Martin Luther. So, even in theRenaissance of professorGBFMtm the fraudulent the ”Red pill” Churchian Church played a role! Now, for the centuries since, ”Redpill” churchians have continued embrace the lie that ”redpill” is practised by the ”redpill” churchian church of liars & deceivers.

Ybarra is an aberration among”Redpill” churchians. Since the tradition of the ”redpill” churchian church should lead to him reject ”redpill” ”manosphere”, he’s forced instead to engage in retroactive continuity. The only reason Ybarra is disagreeing with the ”Redpill” ”rpgenius” ”leaders” and ever-failing years of”redpill” churchian church tradition is because they got caught lying and can’t deny it anymore. Apologists are, quite rightly, not letting them get away with it.

Unsurprisingly, Ybarra is doing a really poor job of covering for the lie. Notably, Ybarra is only willing to sort-of admit what Nicaea was saying. But, he isn’t going to do any of the work to actually undo the centuries worth of doctrinal development based upon a false and fraudulent interpretation. Everyone is just expected to invoke the Axiom and act as if the ”Redpill” soccerdad Authority wasn’t fraudulently developed. He’ll admit that a few details might have been incorrect, but, per the meme, “mistakes were made on both sides.”

So when Michael finds himself convinced by the argument Ybarra gives, I raise the Axiom: it’s really easy to be convinced by an argument when you already axiomatically believed its conclusion. But, then, you were not really convinced by the argument, you only found it convincing. This is a massive difference.

&

Larry G says:

2 October, 2025 at 1:21 pm

Perhaps off topic or not

Last night I came home to fresh-baked modernist cookies by my ”traditional” Mrs. I asked what the occasion was. She told me sweetly that she just wanted to modernist please me and thank me for working hard that gave her a comfortable life. It seems she recalled the times while she grew up not having enough food to eat and clothes to wear, and how her life changed with easy pleasy modern ”traditional”(where the ”woman”=queen just has to cook & look after the d@ng instead of gina breaking work like most women=wives in history did with their husbands every day)marriage to modernist me.

And the modernist cookies were really modernist good

THAT TYPE of comments in the churchian sphere, plus the vast ignorance of the TRUE ”MANOSPHERE” AKA THE ROISSYOSPHERE, shows just how black & white ”redpillers” thinking is as they’re mostly dyed in the wool GOPLGBTQ+supporters anyway & leech on to ”redpill” for MODERNIST ”self-esteem & butthexting empowerment” as they turn their childish GOPLGBTQ+ baseball caps sideways hoping to be seen as ”cool” & ”rational”.

Interesting. I’m only about 25% of the way through this article. But I think you’ve already changed my mind on something. I used to agree with the view that the canons of Nicea were invented at Chalcedon and retrojected into the past. But your explanation of all this jurisdictional wrangling seems to prove that they really come from Nicea. Well done.

IMO, all of the councils were convened for political reasons. They were all power plays of one sort or the other to ensure that certain bishops, cities, and provinces had power over others. Rights were established, confirmed, or removed, altering the balance of power.

If the Nicaean Canons were ahistorical—if the council had never existed—the history of the subsequent councils wouldn’t make sense. The church really did believe that Nicaea had great authority, so they spent lots of time either faking the Nicaean Canons or citing the originals in order to claim Nicaean authority for their POV.

The Council of Nicaea was an ecumenical council that established the rights of Alexandria, Rome, Antioch, and Jerusalem to ordain bishops. It affirmed that the Metropolitan bishops were greater than the other bishops.

The Council of Sardica was a non-ecumenical county that further established rules for cross-territorial disputes. Later Popes would conflate the Councils of Nicaea and Sardica as if they were the same thing, in order to give Sardica’s Canons the weight of authority given to Nicaea. Sardica was essential to Rome’s later bid for supremacy.

The Council of Constantinople was held in order to raise Constantinople to the status of Rome, in an obviously political move. Rome responded to its rival almost immediately with its own Council of Rome where it became the first to declare the primacy of Rome, a novel invention at the time.

The Council of Ephesus dealt with bishops trying to take over the domains of other bishops, to try to squash Constantinople, to create an alliance between Rome and Alexandria against Antioch, and to wreck Nestorius using a show trial. Amusingly, Rome objected to “Saint” Gregory Nazianzus for political reasons.

The Council of Chalcedon was a massive power play of epic proportions, an unholy union of the Emperor and the Bishop of Rome. The show trial of Dioscorus featured prominently.

But, there are clearly three different categories of councils.

First, Nicaea, Sardica, and Constantinople have the air of serious ecumenical severity. They may have been politically motivated, but they were not corrupt to the same extent that later councils were. The Canons are fairly concise.

Second, the Council of Rome was a non-ecumenical that was the one of the earliest councils to be convened for purely political reasons (to undercut Constantinople).

Third, Ephesus and Chalcedon read differently. Reading these councils is somewhat painful, as they are riddled with honorifics and flowery language in epideictic and panegyrical styles. They are pompous and annoying. It’s clear that the church, by these two councils, had fully adopted secular ways.

Also, the Apiarus affair (with Zosimus) predates Chalcedon, and the corrupted Nicaean Canons featured heavily there.