Note: This is part of a series on the Trinity from a rational, non-mystical perspective. See the index here.

Back in “Bruce Charlton on the Trinity,” I made this statement:

I’m actually surprised that it’s taken so many centuries before this inherent relativism within traditional Christianity revealed itself so clearly and plainly in a broad, global, unambiguous way. What doesn’t surprise me is that it comes at a time when “mystical Christianity” is more popular than it ever has been. The fruit of “blind faith” and subjective personal mystical experience has revealed itself for what it is.

After I wrote that, Charlton answered this, saying:

One consequence of which is that incoherent theology is now inescapable, and lethal. It so weakens faith that the religious lack the courage to dissent from the labile impositions of the totalitarian materialist System – even privately in their own minds!

Something fundamental has changed in recent times with the way people think, with their consciousness. Something unprecedented. Where previously there was no real harm with individuals or churchs asserting such things, now it is proving deadly.

Since Charlton is a polytheist, it occurred to me to ask how how polytheist mystics view the Trinity. But, I had written about their beliefs before.

Back in September of last year, in “The Occult in the Mainstream Church, Part 3,” we discussed how three notable figures—John Mark Comer, Michael Heiser, and Ed Hurst (of Radix Fidem)—all expressed polytheistic views. They differed somewhat in how (un)comfortable each was with acknowledging their polytheism, but all nonetheless unambiguously attested to the existence of more than one god.

Interestingly, I’m not the only one who desired this:

Search the 2 godheads in heaven lecture on YT by the late Dr Michael Heiser a biblical scholar. The trinity exists in the OT.

A lot of the logical problems with the Trinity disappear if you give up orthodoxy and assume that there can be more than one god. After all, this is exactly what the Mormons teach. We have to ask if these Christians—Comer, Heiser, and Hurst—are also espousing mainstream beliefs on the Trinity while simultaneously asserting polytheism.

John Mark Comer

John Mark Comer is not your typical Trinitarian. He tends to view the Trinity from the perspective of a community or society, reflecting the virtues of hospitality and love. In this, he reflects non-traditional, progressive, social-justice focused Christianity. In “Practicing the Way” he calls the Trinity “a community of self-giving love.” His mysticism is based in this Trinitarian understanding, where, like the Trinity, people should become rooted in the inner life of God to allows them to experience or feel like God.

In short, Comer’s view of the Trinity is focused more on inclusivity and love than on logic.

Comer’s views on the Trinity are not systematic theological expositions. They are strongly influenced by Ronald Rolheiser—a Roman Catholic priest—and Eastern Orthodoxy.

Comer—a polytheist—is concerned with the spirituality of the doctrine of the Trinity and not concerned at all with its logical consistency.

Reviewer Wyatt Graham writes:

How Comer Describes God Focus on Relationship Over Trinity: Comer rarely mentions the Trinity (Father, Son, and Holy Spirit) in God Has a Name. Instead, he talks about Yahweh (God) and how Jesus interacted with people. While he does speak positively about the Trinity in his book Practicing the Way, his focus is more on entering into God’s love and feeling connected to Him emotionally.

Feeling Like God: Comer believes that through our spiritual growth, we can enter into God’s inner life and even feel what God feels, like His generosity and love.

…

Key Distinction in Theology: Comer often speaks of God as a “relational being,” meaning He interacts with us and experiences emotions. Traditional Christian theology also calls God relational but focuses on the unique relationship within the Trinity: the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. These relationships are eternal and beyond human psychology.

In summary, Comer seems to subscribe to the doctrine of the Trinity, but only to the extent that it provides a mode or analogy for social or community action among Christians and the world. But, in general, the Trinity is just not an important doctrine for John Mark Comer.

Michael Heiser

Like Comer, Heiser is another polytheist whose views on the Trinity are not quite mainstream.

Heiser cites Exodus 33 here where Yahweh proclaims the name of Yahweh. He argues that this is one of a number of examples where the Old Testament describes two Yahwehs. He calls this the Jewish “Two Powers in Heaven” doctrine and claims that it was well-established prior to the 2nd century AD, when it was declared a heresy in Judaism. He claims that:

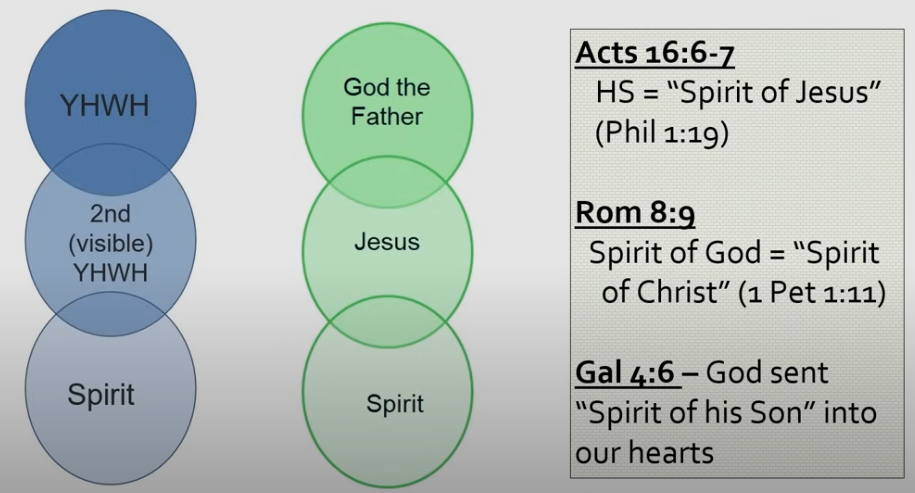

Michael Heiser explicitly disagrees with “Bart Erhman on the Trinity” here by asserting that the Trinity is a doctrine described by the Old Testament. He notes that the Holy Spirit and God are interchangeable in the Old Testament (Isaiah 63:10; Psalm 78:35-41) and that Jesus’ spirit is equated with the Holy Spirit in the New Testament.

Heiser’s views are complex and deviate from the traditional view on a few points, as well as being largely missing from the early, non-Gnostic writers of the church. He does claim to believe in the traditional Trinitarian view, but he describes Yahweh as multiple “elohim” and the Divine Council as made up of different other multiple “elohim.” Only God—the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—is one in three. In this way, he holds to a “monotheistic” One God, but is a polytheist because his divine council is made up of multiple gods.

Heiser does not provide a logical argument in favor of the Trinity, specifically stating that his approach is not proof-texting. He also states that denying three-in-one is an error, but it is not a matter of salvation. For example, he notes that the Arians were called “Brothers” despite holding an “aberrant” belief.

Heiser cites the Gnostics to claim a continuity of belief in the divinity of Christ between the ancient Jews, the Christians, and the Gnostics by using the Gnostic texts as evidence. He understands the description of Jesus from the Gnostic Silvanus as being utterly compatible with scripture, suggesting that specific quotations could be inserted into the Bible without any problems. He does not see the Gnostic view as a corruption of the non-Trinitarian view, but an agreement with it.

Heiser explicitly rejects Adoptionism.

Radix Fidem

Ed Hurst of Radix Fidem declares this about the Trinity:

Our Radix Fidem covenant is neutral on the doctrine of the Trinity. We are neither for it nor against it.

…

[T]he Trinity is a theory of Western minds, neither supported nor denied in Scripture. When the Bible refers to God as Father, Son and Holy Spirit, it speaks of each in terms of human experience. It’s not meant to be regarded as somehow factual. That is, we are flatly told we cannot intellectually comprehend the Father and the Holy Spirit, and we know Christ only from the testimony of trustworthy followers. But we can know God in terms of all three in our hearts in ways that neither the mind can fully grasp nor words can tell.…

The doctrine arose on the tail end of a fierce controversy denying that Jesus was divine. The response to prevent further questions was to nail things down more than necessary.

This is similar—but not precisely the same—to my own view:

Both of us assert that Jesus is divine. The key difference is that I am not a polytheist.

In any case, considering that Radix Fidem is polytheistic, it is unsurprising that it does not feel the need to assert a Trinitarian viewpoint which attempts to maintain a monotheistic viewpoint. The polytheist is not obligated to believe in the Trinity.

Summary

Among the polytheists—who are related to the mystical approaches—there is a rather wide range of understandings on the Trinity. Radix Fidem views the Trinity as non-essential. Heiser views the Trinity as true, but not essential for salvation. Comer views the Trinity as real, but recasts it in terms of theological language of community, spirituality, and community action. All of these men hold views that are alterations of the traditional doctrine of the Trinity.

All three believe in a polytheistic council of gods, but this has not produced a uniformity of belief on the Trinity. Indeed, if anything, the polytheistic view has caused the divergence on the doctrine of the Trinity. This makes sense, as the Trinity is ultimately a compromise between polytheism and monotheism, an attempt to have it both ways at once: three gods (polytheism) in one god (monotheism). If one simply believes in polytheism, there remains no reason to be dogmatic on monotheism. Asserting that more than one god exists is one possible way to resolve the inherent contradiction in the Trinitarian doctrine, and some have chosen to take this path.

However, in our next post, we’ll see what happens when one rationalist polytheist attempts to keep the Trinitarian doctrine as-is.

“Among the polytheists—who are related to the mystical approaches—there is a rather wide range of understandings on the Trinity. ”

Indeed! So much so, that the word seems rather inadequate as a descriptor. Also, it tends to imply something different from what some “Christian polytheists” mean. (Although orthodox mainstream Christians are very keen on equating e. Greek or Roman pagan polytheism with – for instance – Mormon paganism.

It is also worth bearing in mind that Jews and Moslems seem always to have regarded Christians as polytheists. This seems reasonable to me, in that Christians cannot explain in plain language why they are Not polytheists is Jesus was a Man (i.e. Not an avatar or emanation) and also a God – given that the prime creator God (The Father) did not cease his activities for those years when Jesus was incarnated.

(I mean, Christians do Not want to claim that when Jesus incarnated he became the Only divine being.)

Speaking for myself, I am a different kind of “polytheist” now than I was a decade ago. I could not find any coherent explanation for what seemed true, so I had to discover one for myself – which took a few years. Mormonism was on the right lines, but I find that their insistence on the eternal divinity of Jesus means that he had no reason to incarnate and become a Man.

Indeed – most Christian theology gives so much power to God that there is no reason for Jesus.

Many orthodox mainstream Christians are theologically (if not in practice) de facto Moslems, IMO – especially current trad Catholics, and Calvinists; and “manosphere” type Christians.

Since Islam answers their apparently deep and primary demands wrt mens’ relationships with women – I honestly find it increasingly hard to understand why manosphere-Christians persist with their weirdly distorted and unconvincing version of Christianity; rather than simply becoming purely-monotheistic (and coherent) Moslems. Islam is ready made for them – and designed explicitly to be the basis of theocratic nations.

Since Islam answers their apparently deep and primary demands wrt mens’ relationships with women – I honestly find it increasingly hard to understand why manosphere-Christians persist with their weirdly distorted and unconvincing version of Christianity; rather than simply becoming purely-monotheistic (and coherent) Moslems. Islam is ready made for them – and designed explicitly to be the basis of theocratic nations.

I’m glad someone who hasn’t been hit over the head for years with the manosphere-Christian ”leaders” nonsense and gibberish{(mainly) as the ”RP congregations” nearly AMEN everything that spits on women or JESUS NT love=gospel} obsession with the redpill=heavilly watered down ”PUAgame” understands that their ”Christianity” lacks what their proclaimed religion is based=founded on such Scriptures as…

34 I give you a new commandment: that you should love one another. Just as I have loved you, so you too should love one another.

35 By this shall all [men] know that you are My disciples, if you love one another [if you keep on showing love among yourselves].-John 13:34-35 Amplified Bible, Classic Edition

4 Love endures long and is patient and kind; love never is envious nor boils over with jealousy, is not boastful or vainglorious, does not display itself haughtily.

5 It is not conceited (arrogant and inflated with pride); it is not rude (unmannerly) and does not act unbecomingly. Love (God’s love in us) does not insist on its own rights or its own way, for it is not self-seeking; it is not touchy or fretful or resentful; it takes no account of the evil done to it [it pays no attention to a suffered wrong].

6 It does not rejoice at injustice and unrighteousness, but rejoices when right and truth prevail.

7 Love bears up under anything and everything that comes, is ever ready to believe the best of every person, its hopes are fadeless under all circumstances, and it endures everything [without weakening].-1 Corinthians 13:4-7Amplified Bible, Classic Edition

7 Beloved, let us love one another, for love is (springs) from God; and he who loves [his fellowmen] is begotten (born) of God and is coming [progressively] to know and understand God [to perceive and recognize and get a better and clearer knowledge of Him].

8 He who does not love has not become acquainted with God [does not and never did know Him], for God is love.-1 John 4:7-8 Amplified Bible, Classic Edition

17 But if anyone has this world’s goods (resources for sustaining life) and sees his brother and [a]fellow believer in need, yet closes his heart of compassion against him, how can the love of God live and remain in him?-1 John 3:17 Amplified Bible, Classic Edition

8 Keep out of debt and owe no man anything, except to love one another; for he who loves his neighbor [who practices loving others] has fulfilled the Law [relating to one’s fellowmen, meeting all its requirements].-Romans 13:8 Amplified Bible, Classic Edition

44 But I tell you, Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you,

45 [a]To show that you are the children of your Father Who is in heaven; for He makes His sun rise on the wicked and on the good, and makes the rain fall upon the upright and the wrongdoers [alike].-Matthew 5:44-45 Amplified Bible, Classic Edition

Those are some of the main verses that the manosphere-Christian ”leaders” as well as their flunkies and yes men- have feared,detested and rebuked since GBFM started preaching to them at the Dalrock blog on July 6th, 2012(after first mainly preaching to the secularists and agnostics at the CHATEAU ROISSY-Heartiste PUAgame blog that started the entire manosphere rolling on April 9th,2007 as the ROISSYosphere back then it’ll latent leftist blank statists began calling it the manosphere- for over two years)

Pingback: Bnonn Tennant on the Trinity - Derek L. Ramsey

Pingback: Constructive Criticism, Part 3 - Derek L. Ramsey

See also here