This is part of a series on patriarchy, headship, and submission. See this index.

Throughout this series, we had focused on Wayne Grudem’s position on mutual submission. We’ve largely focused on his understanding of the Koine Greek word hypotassø often translated as “to submit” or “to subject” with the sense of being in submission to a leader in authority.

The backdrop to this is the discussion that began on Sigma Frame over a year ago in the comment section under “The Tennant Authority Structure.” At the time I was trying to avoid commenting on Sigma Frame and sticking to my own blog, so I wrote two articles in response: “An Analysis of Genesis 3:16” and “The Context of Genesis 3:16.”

Jack followed that up with its own post “Wayne Grudem’s Study of the Greek Word kephalē, “Head”,” which essentially ridiculed the position that I had been promoting. The timing was such that not a single one of the counterpoints I raised was actually addressed. I suppose everyone assumed that the burden of proof was on me to refute Grudem (something I have not been able to do until I started this series). I’m not sure that I even disagree with that burden-of-proof, but it was disappointing that no one could refute even a single point I raised. As I was unable to quickly respond to such a massive topic—Grudem is a prolific and detailed writer—the whole discussion in the comment section was dead in less than 48 hours.

And that’s been the state of affairs more-or-less ever since.

In Part 7, I concluded by saying:

If this statement is true, it will become evident upon an examination of Jack’s article praising Grudem. So just as we did with Full Metal Patriarch’s review of Grudem’s take on hypotassø, we will need to do the same for Jack’s review of Grudem’s take on kephale. This won’t be the complete review that I’d like to do, but at least it is a start.

Introduction

Let’s start by talking about Deep Strength’s point. Why haven’t I talked about Grudem’s exhaustive study of 2,336 examples? Because calling it exhaustive is misleading almost to the point of deception.

Did you know that of the 2,336 examples, 98% of them refer non-figuratively to a literal head (i.e. the thing on the neck)? That means 98% of his exhaustive study was about something that was completely irrelevant to the discussion. The year before I had already done an “exhaustive” study of the New Testament references in “Kephalē in the New Testament: A Review.” I knew that most were non-figurative:

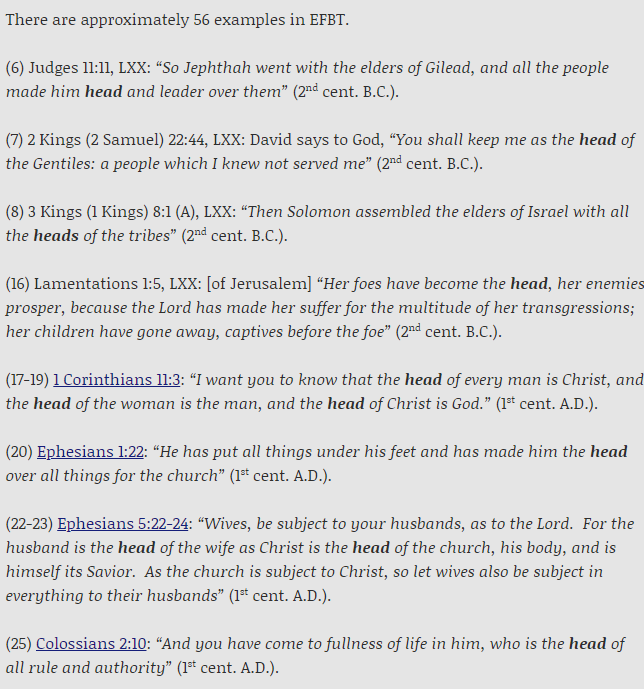

After removing the irrelevant entries, Grudem’s list is left with 49 figurative instances of the word in ancient literature. Over thirty years, Grudem would add 7 more, raising the total to 56. Exhaustive or not, that’s not a huge number.

But even that number is artificially inflated, because merely counting the total number of references is still misleading. One writer here lays out the issues:

Then there is the problem that Grudem’s list involves circular reasoning:

The New Testament references cannot be used, as Grudem does, as proof of what he is setting out to prove about them. We must exclude the passages under debate for the purposes of this discussion.

Once we factor in all of these concerns, we are left with about 20 valid references to consider. By any measure, the figurative usage is relatively rare.

This rarity will make any conclusions—based on an exhaustive study—inherently unreliable. Even if you take hours required to research this topic in depth—including examining all the various perspectives—at minimum you’ll be forced to admit that the evidence is somewhat inconclusive. This will be true even if you eventually come to a particular favored conclusion.

But all of that presumes that Grudem’s methodology and research has no other problems and defects. This is far from the case. Grudem’s argument has deep flaws, which we’ve already shown and will continue reveal and discuss.

The Lexicons

Before we consider the examples Grudem gives, let’s discuss the lexicons. Lexicons are descriptive, informative, and useful, but they are not prescriptive, nor conclusive, nor truly exhaustive (e.g. living vs dead metaphors).

The main problem with lexicons is that they are not independent of the source material nor its translations. A lexicon is a formal inventory of lexemes. A lexicon can easily enumerate the references to a particular word, but how does it know what the meanings of those words are? By looking at—or asserting directly—the translations. But if the translation is under debate, citing a lexicon can prove quite circular.

Here is what Grudem claims:

1 of 7 now give “source” as a meaning of kephalē. (0 of 7 if the correction from the LS editor is counted.)

0 of 7 have ever given “prominent, preeminent” as a meaning of kephalē.

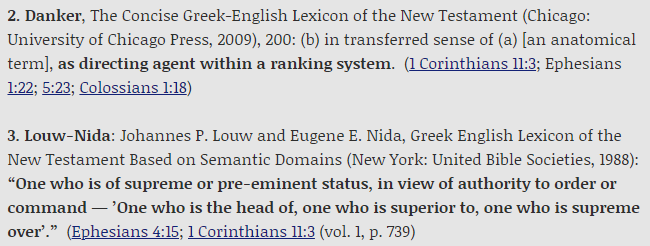

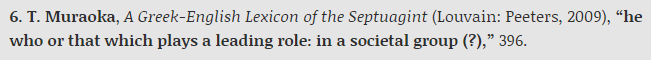

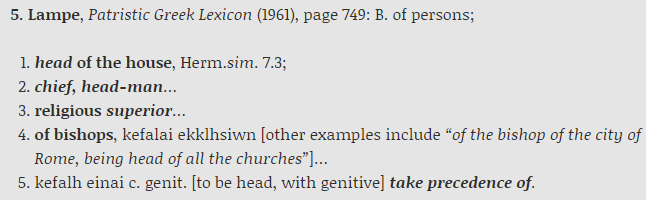

He cites seven lexicons: Danker (2009), T. Muraoka (2009), BDAG (2000), Lust (1996), Louw-Nida (1988), LSJ (1968), and Lampe (1961).

Reading Grudem’s claim, you might conclude that this is an exhaustive list of lexicons, but it is not.

(1) The list only includes modern lexicons. Many of the older lexicons do not agree with Grudem’s claim. This discrepancy cannot be explained solely on the basis of new documents being revealed over time. One must consider whether or not there was a fundamental change in the assumptions of the lexicographers themselves. Lauri Fasullo asserts this (emphasis added):

This is an interesting claim. This is the same type of circular reasoning that Grudem used above and the same type of circular reasoning that he used with the discussion of hypotassø and mutual submission. We will highlight more examples of this below.

(2) Per Lauri Fasullo, it excludes the following lexicons: Moulton and Milligan, Friedrich Preisigke, Pierre Chantraine, E. A. Sophocles, and S.C. Woodhouse. Richard S. Cervin noted, in 1989, that none of the secular Greek lexicons from the 1800s and 1900s contain the meaning of authority or leader, with the exception of one by D. Dhimitrakou in Athens who explicitly states that the meaning of ‘leader’ was medieval.

(3) The lexicon’s use of the Septuagint militates against Grudem’s claim. So rare is the translation of ‘leader’ or ‘authority’ from Hebrew into Greek as kephale (at most, arguably, 4-6%) that it indicates that this understanding of kephale must have been mostly (or even completely) unknown in the Greek-speaking world.

Now let’s look at Grudem’s claim:

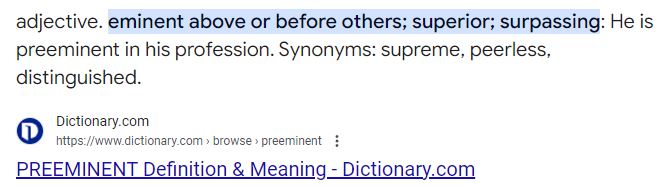

For quick reference, here is the definition of preeminent:

Note that the definition of preeminent is ‘superior’ and that it is synonymous with ‘supreme.’

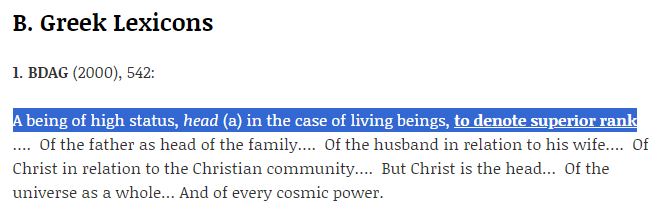

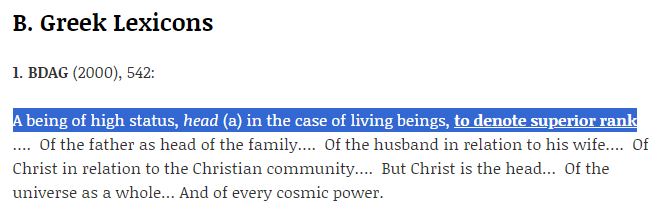

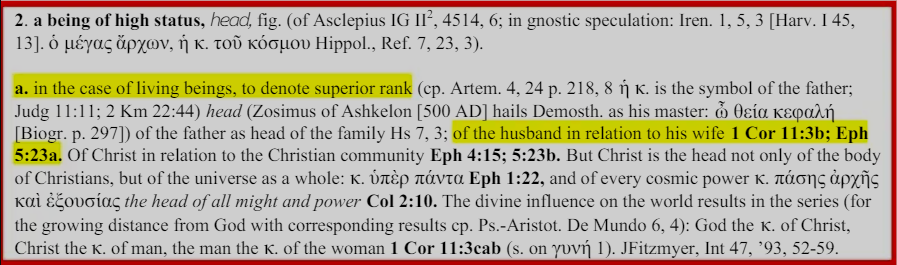

Now let’s look at Grudem’s citations, starting with one of the most important and commonly used, the BDAG lexicon:

In his very first example he gives an example of a head denoting being superior, of higher status!

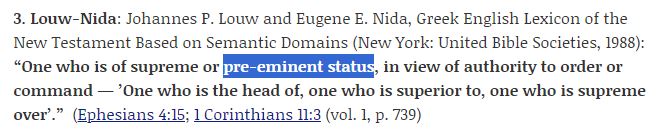

In only his third example he gives a definition that explicitly gives a meaning of “pre-eminent status”, “supreme,” and “superior.” It’s all right there: “Pre-eminent.” “Supreme.” “Superior.”

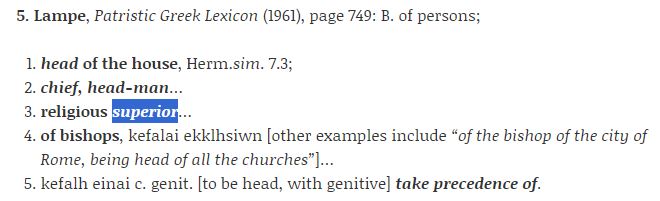

Again, in the fifth example we see the meaning of superior. It is in a restricted context of religious superiors, but that’s just fine. It nonetheless still matches the definition of preeminent.

Three of his six examples where the lexicons say that kephale means authority—half of them—refute his own claim outright! We didn’t even have to do any research on the subject. We just had to read what he wrote and see him contradict himself. When I read this, I instantly saw the contradiction. Grudem’s claim is obviously false.

After seeing this most basic of errors, I’m astonished that people take Grudem seriously. Having seen this, if not for his massive popularity, I doubt that anyone would even bother to refute his work.

But it doesn’t end there. Did you notice all the ellipses (“…”) that Grudem added to that BDAG reference?

Here is that same reference in its complete context:

First, there are only two secular references. Almost all of the references are from the Bible. As Fasullo noted, this is a case of already assuming the meaning of a word in order to use a passage to prove its meaning. There is nothing wrong with BDAG, a lexicon, doing this. The problem is that Grudem’s citation of BDAG as proof of the Biblical interpretation is plainly circular. Grudem’s use of ellipses hides this misuse.

Second, one of the two secular references is from Zosimus in 500AD. This is a medieval reference. As I’ve stated throughout this series, the common meaning of kephale as ‘leader’ or ‘authority’ is medieval (although it began to arise in the late 4th century). This is far to late to be used as proof for what Paul meant. This citation is irresponsible of DBAG to use. Grudem’s use of ellipses hides this. Moreover, the reference itself is not even clearly about authority:

It is virtually certain that this passage does not imply a position of authority over anyone. Stanford classicist Mark Edwards stated that ho theia kephale in the Zosimus document is a salutation implying dignity, not authority. Presumably, the Demosthenes referred to is the great Athenian orator (384-22 B.C.), who could not have had a position of authority over Zosimus since Demosthenes had died over 800 years earlier.

Third, the second of the two secular references is not obviously about authority either.

He also said:

Bauer’s reference may be an example of a lexicographer reading his own cultural understanding (i.e., fathers have “superior rank”) into the text.” (Mickelsen & Mickelsen, “What Does Kephale Mean in the New Testament?,” in Women, Authority and the Bible, ed. Alvera Micklesen, p.100)

As this may actually be an example where kephale means source, rather than authority, it is understandable why Grudem might want to leave this inconvenient part out of his quotation.

Continuing on, we further note that two of his references are explicit in their descriptive definitions of kephale as authority by citing Bible references only:

Grudem’s citation of these is inherently circular. New Testament lexicons cannot be used to prove that what is contained in the New Testament is the correct interpretation.

These observations illustrate the idea that any idea can be convincing if you only hear one side. It is only those ideas that can sustain scrutiny from multiple sides that truly matter, but Grudem’s claims regarding the lexicons fail this utterly. But we have two more examples that requires their own section: The Septuagint.

The Septuagint

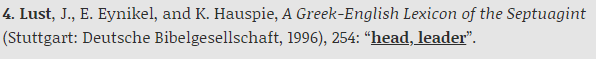

Two of Grudem’s seven cited lexicons are lexicons of the Septuagint:

In Hebrew the word for “head” (‘rosh’) meant the literal head, top or physical extremity, leader or ruler, and origin, first, or possibly even source (per here and here). While the word is mostly used in the Old Testament to refer to literal heads, it has 180 separate figurative uses.

The Septuagint translators were not shy in using the Greek work kephale—they did so ~373 times. However, the Septuagint translators chose a different Greek word—not kephale—to represent the Hebrew original in almost all of the 180 instances where rosh had a metaphorical meaning. The exact count is debated because some of the translations have variant readings and others exclude the head-tail metaphor. There are roughly 9 (give or take) instances where rosh meant ‘leader’ or ‘ruler’ and was actually translated into kephale. The large majority of the time a different word was chosen.

Of these ~9 references, a total of four are reasonably considered to be about rule and authority and also translated into kephale:

2) Ps 17:44 (18:43): “Deliver me from the contradictions of the people; you will establish me as the head (eis kephalēn)) of the Gentiles; a people I never knew served me….”

3) Jer 38:7 (31:7): “For thus says the Lord to Jacob: Rejoice and exult in the Head (epi kephalēn) of the nations. Make a proclamation and praise Him. Say, ‘The Lord saved His people, the remnant of Israel.’”

4) Lam 1:5: “Her oppressors have become the master (eis kephalēn), and her enemies prosper; For the Lord humbled her because of the greatness of her ungodliness.”

Thus, the value of the LXX has been overrated as evidence for kephalē connoting “leader” or “authority.” The relatively few uses of kephalē as a metaphor for leader can best be explained as due to Hebrew influence.

The Septuagint translators did not view the Greek kephale as an equivalent to the Hebrew rosh.

A number of the examples of translating rosh into kephale can be explained as Hebrew translators being hyper-literal in their translation: translating the literal head in Hebrew into the literal head in Greek, even though the meaning was figurative. This would, of course, only result in confusion as Greek-speakers wouldn’t understand the metaphor when translated literally. In other words, they were bad translations that slipped through.

On the other hand, if we assume that kephalē were a common and prevalent Greek metaphor for leader, then that same well-established Hebrew metaphor (ro’sh = “leader”) should be perfectly transferable into Greek and we should expect a nearly 100% translation rate: ro’sh = kephalē (leader). However, this has simply not occurred. It strikes me as very odd that the translators of the LXX would choose to disregard a metaphor which is allegedly perfectly translatable from Hebrew to Greek, especially in light of the many literalist, and sometimes un-Greek, translations which were foisted on the Greek text of the LXX elsewhere. Those who argue for “authority” have not adequately explained this problem.

Men like Grudem like to cite the few examples in the Septuagint as supporting the notion that kephale always means authority, but they have to do so while ignoring the wide majority of cases where translators didn’t conform to that belief. This is, to put it gently, questionable at best. At the very least this is a primary difficulty that has to be addressed before one accepts Grudem’s claims.

The best inference from the large majority of cases in the Septuagint is that kephale did not imply rule, leadership, or authority.

So what else does the lexicon of the Septuagint tell us about kephale? Not much at all. Whether a particular of kephale in the Septuagint implied authority is essentially determined by context or the original Hebrew, not the word kephale chosen in the Septuagint. After all, each time a translator failed to choose kephale, he indicated that kephale was not the best translation for rosh. Moreover, there are a number of cases where the translation went from rosh (as ‘leader’ or ‘ruler’) to some other Greek work in the Septuagint before finally being translated into the English as ‘head’.

In any case, since the Septuagint is a Hebrew-to-Greek translation and not a native-Greek work, it can only be treated as a secondary source when evaluating the evidence.

When one removes the New Testament (for reasons of circularity) and Septuagint (for reasons of weak evidence) lexicons from Grudem’s list of seven lexicons, his weak conclusions are further revealed.

The Examples

Given how weak and invalid Grudem’s claims above are, I am not inclined to spend much time individually refuting the specific examples he cites. Just as his claim that all of the Bible references to hypotasso were always about authority was obviously false, so too is his claims that all of the metaphorical references of kephale referring to authority also obviously false. For the latter, we only needed to find one counterexample, but we found many instead. Here too we’d only need to find one counterexample, but there are many. We need not disprove all of his examples to disprove his claim.

Grudem’s cherry-picking is best revealed by his failure to include 170 instances where the Hebrew rosh (as ‘leader’ or ruler’) was not translated into the Greek kephale. At least one of these must count as an example of kephale not carrying the sense of authority or rule. Grudem may have excluded evidence that didn’t support his claim, but we are not required to do so.

And a reminder for those who have read this far: Grudem’s 56 examples that kephale means authority includes biblical references. For example:

It is very challenging to take seriously someone who wantonly engages in circular reasoning. We’ll invoke the Principle of Charity and merely ignore these as irrelevant to his argument.

For instance, example 17 cites the seven spirits that are head of the “works of youth” (which seems to mean “foolhardy actions”). But how does one hold authority over actions? Perhaps one can, and perhaps cities can rule, too (examples 11-14, Isaiah 7:8-9) but these don’t seem all that clear-cut.

Other examples that don’t seem to help much are 21-22 which propose that a good person is like a head and that the head animates the body. However, this is not the same as rule. Indeed, this seems to suggest another alternative for “head” entirely (the animating principle).

Examples 44, 47, and 49 (Ephesians 1:22, Colossians 1:18, and Colossians 2:18–19) suffer from a similar body problem: Christ is head over the church which is a body but this is not an entirely clear metaphor despite our attempts to make it so.

…and…

Examples 1-2, for instance, refer to the full citizens of Argos as “head”. Argos is a monarchy (the same document, 7.148.17) and so if kephale means “authority over” it seems to me that the king should be head and the full citizens something less.

In 15-16 (Isaiah 9:14–16) one group of leaders is the head but another is the tail. Since these are opposites elsewhere, I would require a lot of convincing that we should simply ignore this “tail” business.

In example 19 Grudem would have us believe that Ptolemy Philadelphus ruled over the Ptolemies. He clearly didn’t, in large part because he wasn’t alive when most of the other Ptolemies (his ancestors and descendents) reigned. Instead, he excelled in kingship beyond them.

Given this, “authority over” just doesn’t seem to be a great fit.

Here are a few secular examples where you can see how much Grudem is stretching to make his concept fit. Grudem wants you to believe that in each of the 56 examples, authority is the best explanation. But this just isn’t the case when you actually look at them.

Regarding Ptolemy Philadelphus, I had written about this one a couple years ago in “The Head-Body Metaphor.”

Here he does not use the head-body metaphor, but we can see from his use how he understood the Greek word for ‘head’, which did not mean ‘leader’ or ‘authority’. Ptolemy Philadelphus was not literally the leader of all kings, he was superior to them. He was the preeminent king among all kings. It was his actions—glorious and praiseworthy—that made him superior.

In that same article I talked about the use of ‘head’ in Philo’s “On Rewards and Punishment,” Plutarch’s “The Life of Pelopidas,” Ignatius’ “Epistle of Ignatius to the Trallians,” and Clement’s “First Epistle of Clement.”

Examples 34 and 48 (Ezekiel 38:2, Colossians 2:10) both include other ruling words (“ruling head” and “head of all rule and authority”) and so its not clear why “head” is the word that indicates rule. None of these should have been counted as positive evidence for “authority over” and are difficult to fit into that model.

A number of writers have gone through Grudem’s list of citations and explained why “authority” is not the best explanation. While the above explanations should be more than sufficient, check out the works by Richard S. Cervin, linked below, if you want a more complete counterpoint.

A Note on John Chrysostom

(56) Chrysostom, Homily 15 on Ephesians (NPNF series 1, vol. 13, p. 12; TLG Work 159, 62.110.21 to 62.110.25): [To a woman, on how to treat a servant girl] “Consider that thou art her mistress, and that she ministers unto thee. If she be intemperate, cut off the occasions of drunkenness; call thy husband, and admonish her…. Yea, be she drunkard, or railer, or gossip, or evil-eyed, or extravagant, and a squanderer of thy substance, thou hast her for the partner of thy life. Train and restrain her. Necessity is upon thee. It is for this thou art the head. Regulate her therefore, do thy own part.” [In this example, a woman is called the head of her maidservant.] (4th cent. A.D.).

We’ve mentioned John Chrysostom on numerous occasions with respect to his understanding of hypotassø. Grudem is quick to cite Chrysostom as an expert on kephale, even though Grudem doesn’t agree with his expertise on hypotassø. The problem is that if you are going to cite Chrysostom as an expert on Greek, you have to do so consistently.

Many do not think Chrysostom actually taught that kephale implied authority (i.e. they believe that Grudem is taking Chrysostom out of context). But let’s assume otherwise for sake of argument. Wouldn’t that make me just as inconsistent as Grudem, only citing Chrysostom when it suits me? Recall what I said at the end of Part 4:

I’m well aware that Chrysostom had a personal belief in patriarchy. His alleged understanding of kephale reflects one of the earliest references to the word that gives it the connotation of authority. But, as we showed above in the secular lexicons, this usage was not yet found in a secular context, for the Roman Catholic church was only newly arisen. It would take another century or so before the novel medieval usage would become more prominent. As far as I can tell, hypotassø never underwent the kind of major language shift that kephale did.

Do you see the difference? My citation of Chrysostom as a native-Greek speaker acknowledges that he was more-or-less accurate on those words and others. But Grudem cannot make that claim, because he doesn’t think the language changed. His argument requires him to conclude that the meaning of these words was constant and universal from the 3rd century BC into the medieval period. So on one hand Chrysostom understood his language correctly, but on the other he just didn’t understand his own language at all. Does that sound plausible?

Summary

Now let’s review. Grudem cited seven lexicons and claimed that:

However, upon examination we find that most of them do not constitute evidence supporting his claim.

- Two (three if you count BDAG) cite the New Testament, which Grudem is raising as proof of his New Testament interpretation—plainly circular.

- Two cite the Septuagint, which strongly militates against Grudem’s position

- One, the LSJ, does not support his claim at all, the letter from the editor notwithstanding.

- One, the BDAG, uses references that do not constitute proper evidence to support the claim being made.

That leaves just one reference—not six or seven—that could possibly support his claim:

Here is the official description of the lexicon:

This is a lexicon of Patristic Greek, not of 1st-century Greek. While this is still useful, as we’ve seen in our citation of Chrysostom, it of course cannot constitute direct contemporary evidence of Paul’s Greek language. It is thus, at best, of secondary value only.

And, notably, because it is restricted to “unusual or unique senses for the patristic authors” it potentially suffers from bias by the lexicographer who is forced to make speculative leaps to account for unusual uses. It is not clear how a lexicon of unusual uses applies generally to Paul. To make such a connection would require a direct citation where the patristic writer cited Paul directly, as in our example of Chrysostom. For example, it would benefit little if a 3rd or 5th century patristic writer wrote in an obscure and rare way of a completely separate topic unrelated to Paul.

Lastly, Lampe, at best, shows that kephale can mean chief or head-man, not that it must mean that. It certainly does not always imply authority in each of the definitions.

In any case, Grudem’s citation of these seven lexicons leaves much to be desired. He has vastly oversold their support of his claim. Next, when we then look at some of the examples that Grudem cites, it only becomes more clear that Grudem’s proof is speculative and overblown.

Further Reading

- Wayne Grudem, “Does κεφαλή (“Head”) Mean “Source” Or “Authority Over” in Greek Literature? A Survey of 2,336 Examples” (1985)

- Wayne Grudem, “Meaning of Kephale After 30 Years” (2015)

- Richard S. Cervin, “Does kephale (‘head’) Mean ‘Source’ or ‘Authority Over’ in Greek Literature?’: A Rebuttal.” (1989)

- Richard S. Cervin, “On the Significance of Kephalē (“Head”): A Study of the Abuse of One Greek Word.” (2016) (html version)

- Marg Mowczko, “LSJ Definitions of Kephalē.”

- Marg Mowczko, “Kephale and “Male Headship” in Paul’s Letters.”

- “κεφαλή,” Wiktionary

- “A Meta-Study of the Debate over the Meaning of “Head” (Kephale) in Paul’s Writings” CBE International.

- Stephen Bedale (1954)

- Morna D. Hooker (1963-64)

- Robin Scroggs (1972)

- Fred D. Layman (1980)

- James B. Hurley (1981)

- Gilbert Bilezikian (1985, 1986)

- Berkeley and Alvera Mickelson (1979, 1981, 1986)

- Wayne Grudem (1985, 1990, 2001)

- Walter L. Liefeld (1986)

- Catherine C. Kroeger (1987)

- Richard S. Cervin (1989)

- Joseph A. Figzmyer, S.J. (1989,1993)

- Andrew C. Perriman (1994)

- Judith Gundry-Volf (1997)

- Gregory W. Dawes (1998)

- Anthony C. Thiselton (2000)

- Eric, “A Bad Answer is Worse than No Answer: Kephale and Authority 1” (and part 2)

- Wade Burleson, “Source, not Authority: The Meaning of the Greek Word Kephale in the Bible.”

- Ian Paul, “‘Head’ does not mean ‘leader’ in 1 Cor 11.3.”

- See the updated post: Marg Mowczko, “4 reasons ‘head’ does not mean ‘leader’ in 1 Cor. 11:3.”

Hello Derek. Thank you for this comprehensive article. There’s lots of useful information here.

I have a more recent version of “’Head’ does not mean ‘leader’ in 1 Cor 11.3” than the one posted on Ian Paul’s website:

https://margmowczko.com/head-kephale-does-not-mean-leader-1-corinthians-11_3/

Thank you. I’ve added a link to the article in the list.

Pingback: Habitually Being Wrong

Pingback: Mutual Submission, Part 10

Pingback: Headship Is Still Not Authority

Pingback: On Head Coverings, Part 1 - Derek L. Ramsey