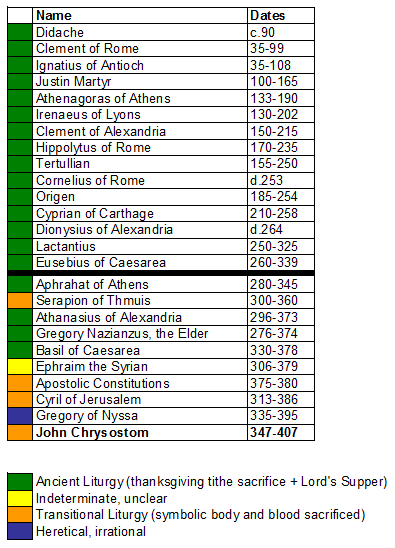

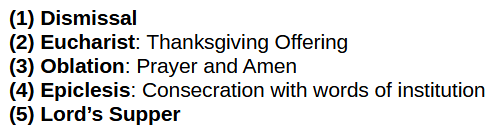

The original liturgy:

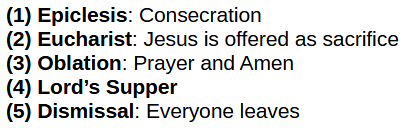

The Roman liturgy:

John Chrysostom (347-407)

John Chrysostom was an extremely prodigious writer, composing around 700 sermons, 250 letters, and a number of other works, including biblical commentaries. He wrote all of his works during the transitional period during the rise of Roman Catholicism. His writings reflect the changes in the development of doctrine, and he most assuredly contributed to that change. At times he seems to support the ancient liturgy and at other times is more suggestive of the Roman liturgy. Sometimes he tried to have it both ways.

Citation: John Chrysostom, “Epistle to Caesarius.” Biblicalcyclopedia

This epistle was discovered in the 16th century and it was declared a forgery by the Roman Catholic Church, for reasons that are pretty obvious: John Chrysostom is denying the doctrine of transubstantiation. But though this belief was not Roman, it was also not an anachronism. We have, of course, seen this view many times in the writers prior to Chrysostom, but it also exists in writers after Chrysostom (but still in the 5th century). Augustine (in “Exposition of Psalm 99” ¶8), Theodoret, and Pope Gelasius (“Against Eutyches and Nestorius.” See: Philip Schaff, “History of the Christian Church, Volume III” ; authenticity is also doubted by Roman Catholics) denied transubstantiation.

(Regarding forgeries, even if a document is a forgery, if it was forged prior to the Reformation, it still constitutes evidence of pre-existing belief in a non-Roman liturgy during that time period. It doesn’t become useless even if it is misattributed and non-canonical. For example, Apostolic Constitutions is a forgery, but still important.)

Citation: John Chrysostom, “Homily 24 on 1 Corinthians.” ¶7

As we’ve pointed out before, there exist a portion of Roman Catholics who believe that the bread must be received only on the tongue, due to the reverence owed Christ’s body. John Chrysostom begs to differ. Chrysostom’s florid prose has him kissing and biting the bread, like two lovers making out. This is reminiscent of Cyril providing instructions to touch the consecrated bread to all the sense organs.

Citation: John Chrysostom, “Treatise on the Priesthood, Book III.” ¶4

This is another colorful (literally, “empurpled”) description of the Lord’s Supper. What are we to make of these wild figures of speech?

Recall how in Part 28: Basil of Caesarea, he said that the bread was displayed and prayers was offered? We see this formula here. The body of Christ is on display and the priest is offering prayers. But in the statement “praying over the victim,” there is a very clear, visceral sense here that the priest is—in wildly colorful, figurative manner—by pure reason through the eyes of faith, offering Christ’s body as a propitiatory sacrifice for the remission of sin, as we saw in Part 29: Serapion, Cyril, Gregory Nazianzus (the Younger), and Apostolic Constitutions.

Citation: John Chrysostom, “Homilies on Betrayal of Judas.” EWTN

Although not FishEaters, Roman Catholic apologists like to cite this quotation as proof that Chrysostom believed in transubstantiation. But, this is unfounded. Chrysostom, as we’ve seen, uses colorful, figurative language to describe how the bread is a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice. But this transformation, just like each of us being “empurpled” during the Lord’s Supper, is a spiritual one visible only by pure reason through the eyes of faith.

Notice here that Chrysostom clearly separates the (2-3) sacrificial gifts from the (4) consecration by the words of institution. The order of the ancient liturgy is maintained. The unconsecrated sacrificed elements are transformed into consecrated unsacrificed elements. This is not a Roman liturgy.

“But,” you ask, “what happened to the priest offering the victim as propitiatory sacrifice for the remission of sin?” Chrysostom wrote during an age of transition when the innovations of the Roman Catholic Church were developed. In many ways he is trying to juggle together the ancient liturgy with what would become the Roman liturgy in the 6th or 7th century. He is, in many ways, describing both at the same time. This is a bit confusing logically, but his colorful, figurative, almost poetic language covers over the apparent discrepencies.

This fact is clearly demonstrated in our next quotation:

It is not another sacrifice, as the High Priest, but we offer always the same, or rather we perform a remembrance of a Sacrifice.

Citation: John Chrysostom, “Homilies on Hebrews, Homily 17.” §6

The Roman Catholic will read this and go “See! See! He is offering the body of Christ as a sacrifice!” and he’d be completely correct. Meanwhile, the ancient liturgist would say “See! See! He clarifies that what he means is that the sacrifice is a figure and a remembrance of a sacrifice!” and he’s be correct as well. There is no way around this. Chrysostom is clearly trying to have it both ways at the same time. Frankly, he can’t seem to make up his mind which he is, so he just vacillates between the two.

This confusion is what we’ve come to expect as the early writers wrestled with how to integrate the doctrinal development—which began around 350—into the next generation of the liturgy and common practice—as Chrysostom wrote around 400.

It is interesting to see how the doctrinal innovation was rationalized away. Clearly Chrysostom was bothered by the direct implications of what he was saying, for he didn’t want to just come out and say it explicitly. There was something inherently wrong about calling Christ’s body—in the form of the bread of the thanksgiving—a sacrifice. See how he struggled over the implications of whether it was one sacrifice or many (i.e. a “re-sacrifice” or “re-presentation”)?

Let’s examine another quotation popular with Roman Catholic apologists. In doing so, we will continue to see Chrysostom’s Jekyll and Hyde coming through:

For His word cannot deceive, but our senses are easily beguiled. That has never failed, but this in most things goes wrong. Since then the word says, This is my body, let us both be persuaded and believe, and look at it with the eyes of the mind.

For Christ has given nothing sensible, but though in things sensible yet all to be perceived by the mind. So also in baptism, the gift is bestowed by a sensible thing, that is, by water; but that which is done is perceived by the mind, the birth, I mean, and the renewal. For if you had been incorporeal, He would have delivered you the incorporeal gifts bare; but because the soul has been locked up in a body, He delivers you the things that the mind perceives, in things sensible.

How many now say, I would wish to see His form, the mark, His clothes, His shoes. Lo! You see Him, Thou touchest Him, you eat Him. And thou indeed desirest to see His clothes, but He gives Himself to you not to see only, but also to touch and eat and receive within you.

Citation: John Chrysostom, “Homily 82 on Matthew.” §4

In this we see the Chrysostom that we’ve seen elsewhere. It is plain that he views Christ’s body and blood as not being literally physically present, but spiritually or mentally present in the mind. He even says that the elements are there to remind you of his teachings, a reference of the Last Supper to John 6 and Isaiah. But he also talks about the physical mark, clothes, and shoes and says that when we eat the body and blood of Christ, it is as if you also touch those physical things.

But Chrysostom, in the same homily, also says this:

But the evening is a sure sign of the fullness of times, and that the things were now come to the very end.

And He gives thanks, to teach us how we ought to celebrate this sacrament, and to show that not unwillingly does He come to the passion, and to teach us whatever we may suffer to bear it thankfully, thence also suggesting good hopes. For if the type was a deliverance from such bondage, how much more will the truth set free the world, and will He be delivered up for the benefit of our race. Wherefore, I would add, neither did He appoint the sacrament before this, but when henceforth the rites of the law were to cease. And thus the very chief of the feasts He brings to an end, removing them to another most awful table, and He says, Take, eat, This is my body, Which is broken for many.

Citation: John Chrysostom, “Homily 82 on Matthew.” §1

Chrysostom calls the bread and wine types—figures. What is contained in the bread and wine? Not flesh and blood, but truth. When the early writers connect Malachi’s prophecy and Jesus’ Bread of Life narrative (in John 6) to the Samaritan Woman at the Well (in John 4), they note that our sacrificial worship is in Spirit and truth. It is unsurprising, then, that Chrysostom finds, in the bread and wine of the Lord’s Supper, Christ’s spiritual presence and Christ’s teachings and truth.

Now we turn to Chrysostom’s liturgy:

(This litany is offered only if there are remembrances for the deceased.)…

Priest: All ye catechumens, depart! Depart, ye catechumens! All ye that are catechumens, depart! Let no catechumens remain! But let us who are of the faithful, again and again, in peace pray to the Lord…

You have served as our High Priest, and as Lord of all, and have entrusted to us the celebration of this liturgical sacrifice without the shedding of blood.

…

Enable me by the power of Your Holy Spirit so that, vested with the grace of priesthood, I may stand before Your holy Table and celebrate the mystery of Your holy and pure Body and Your precious Blood. To You I come with bowed head and pray: do not turn Your face away from me or reject me from among Your children, but make me, Your sinful and unworthy servant, worthy to offer to You these gifts. For You, Christ our God, are the Offerer and the Offered, the One who receives and is distributed, and to You we give glory, together with Your eternal Father and Your holy, good and life giving Spirit, now and forever and to the ages of ages. Amen.

…

…

Citation: John Chrysostom, “Divine Liturgy.”

There is much to comment on here! Notice the similarities and differences between this liturgy and the ancient and Roman liturgies.

As we saw in Part 29: Serapion and Part 24: Cyril—both writing around 350AD—prayers for the dead were one of the earliest introductions into the liturgy, preceding even the offering Christ’s body as a sacrifice. With Cyril, we saw how his critics argued against their practice. But in Chrysostom’s liturgy—roughly five decades later—they were featured prominently.

After the prayers for the dead, we see the (1) Dismissal. But it is no longer the same dismissal found in the ancient liturgies. Here only the catechumens are dismissed, and there is another dismissal at the end of the liturgy! Recall earlier this entry from the Catholic Encyclopedia:

Citation: Adrian Fortescue, “The Origin of the Mass.” The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol 9. (1910)

The Catholic Encyclopedia saw the two dismissals: of the catechumens (“missa catechumenorum”) and the baptized believers (“missa fidelium”), and simply could not understand why the “Mass” took on the name that it did. But as we’ve seen throughout this series, there was once only one dismissal, and it involved the unbelievers, the catechumens, and any faithful who had unrepented sin. They were unable to explain the name “Mass” because the reason for the dismissal is that only the faithful, baptized, repentant believers could participate in the tithe offering, as Jesus himself taught. We saw how earlier writers clearly cited Christ’s words in Matthew regarding the Dismissal, but Chrysostom seems only concerned with whether the participants are baptized. Chrysostom’s—and his contemporary Augustine’s—liturgy was simply too far removed from the words of Christ and the Apostles.

In “the great entrance,” the sacrifice of the bread and wine—the body and blood of Christ—is completely unambiguous. Based on Chrysostom’s other writings, he almost certainly understood the bread and wine as figures of the body and blood of Christ (i.e. not transubstantiation), but he certainly viewed it as a sacrifice.

This is made abundantly clear because the (3) sacrificial thanksgiving prayer occurs after the (4) consecration of the elements. Chrysostom’s liturgy flips the order around. Thus, the consecrated bread and wine being offered as a sacrifice is made plain as day. This is a decidedly Roman liturgical change.

In Part 16: Apostolic Constitutions, we saw how, in 375-380, the tithe was altered so that no longer were all agricultural products offered. Rather, those that were not related to the production of bread and wine were sent straight to the house of the bishop! Only a couple decades later, Chrysostom was able to merge the thanksgiving and the consecration of the bread and wine because it no longer included other agricultural products: he wasn’t consecrating oil or cheese.

The same is true of the tithe no longer being about giving to the poor. Recall how Gregory Nazianzus the Elder and his wife Nonna were known—prior to 375—for their devout fervor and generosity in their thanksgiving? That sense is completely missing from Chrysostom. The vacuum produced by removing the tithe for the poor was filled with a sacrifice of Christ’s body, administered by clergy who took those gifts into their own houses.

There are many other quotations that we could examine from Chrysostom. He spoke of the body and blood of Christ on many occasions. But that seems unnecessary.

In my opinion, the liturgy of Chrysostom correctly sums up his beliefs: a more Roman liturgical order where Christ’s figurative body an blood are offered as a propitiatory thanksgiving sacrifice for the remission of sin.

I also conclude that Chrysostom left a lot of things vague, because he never could completely rationalize it. Like his contemporary Jerome, he conflated of the mysteries and the sacraments, and this certainly colored his viewpoint. A lot of his confusion must have been contained in his belief that the sacraments were mysteries (in the modern sense): unknowable secrets. Recall that we had discussed this in more detail in Part 34: Hilary of Poitiers.

One final note. Chrysostom is clearly sacrificing bread and wine. For the Roman Catholics who say…

…this defense cannot apply to Chrysostom. Chrysostom sacrificed the bread and wine as bread and wine. He may have agreed that the bread and wine was also the body and blood of Christ, but at the very least it was both at the same time—consubstantiation. By contrast, in the first 300 years of the church, no sacrifice of consecrated bread and wine ever took place. In the late 4th century—corresponding to the rise in Roman Catholicism—consecrated bread and wine, which symbolically represented Christ’s body and blood, were sacrificed in an idolatrous act.

Later, the Roman Catholic Church would try to avoid this idolatry in its conceptualization of the Real Presence and Transubstantiation…

…but there is no question that the doctrines developed out of idolatry. Indeed, it seems that the purpose of these other novel doctrines was to rationalize away the idolatry by burying it under complex technical jargon, as there was nothing apostolic about it.