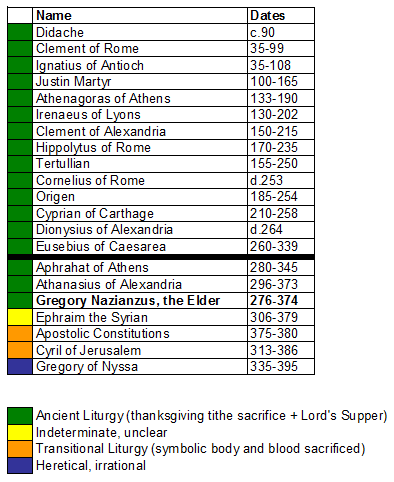

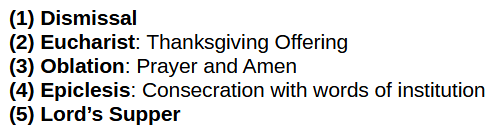

The original liturgy:

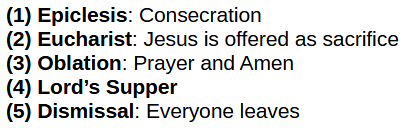

The Roman liturgy:

Gregory Nazianzus

There are two Gregory Nazianzus, the younger (329-390) and his father the elder (276-374). The following oration was delivered by the son when his father died. It is a funeral oration and eulogy.

…The only safe and inviolable form of wealth is, [Gregory the Elder’s wife Nonna] considered, to strip oneself of wealth for God and the poor, and especially for those of our own kin who are unfortunate; and such help only as is necessary, she held to be rather a reminder, than a relief of their distress, while a more liberal beneficence brings stable honour and most perfect consolation…

…and what is still more wonderful, [Nonna] never so far yielded to the external signs of grief, although greatly moved even by the misfortunes of strangers, as to allow a sound of woe to burst forth before the Eucharist, or a tear to fall from the eye mystically sealed, or any trace of mourning to be left on the occasion of a festival, however frequent her own sorrows might be; inasmuch as the God-loving soul should subject every human experience to the things of God…

Citation: Gregory Nazianzus, “Oration 18.” §8,10 (378)

We begin with Gregory the Elder’s wife Nonna, who had a great and sincere concern for the poor. Her son tells how during the Eucharist, which is the thanksgiving, she nobly kept the solemn silence and held back her tears, rather than let her grief over the poor overwhelm her. Why would she become emotionally overwhelmed over the state of the poor during the Eucharist? Because (2) the eucharist was the tithe offering for the poor.

But if you thought Nonna’s eucharist was especially pious, Gregory the Elder’s eucharist was even greater.

Who was more anxious than he for the common good? Who more wise in domestic affairs, since God, who orders all things in due variation, assigned to him a house and suitable fortune? Who was more sympathetic in mind, more bounteous in hand, towards the poor, that most dishonoured portion of the nature to which equal honour is due? For he actually treated his own property as if it were another’s, of which he was but the steward, relieving poverty as far as he could, and expending not only his superfluities but his necessities — a manifest proof of love for the poor, giving a portion, not only to seven, according to the injunction of Solomon, Ecclesiastes 11:2 but if an eighth came forward, not even in his case being niggardly, but more pleased to dispose of his wealth than we know others are to acquire it; taking away the yoke and election (which means, as I think, all meanness in testing as to whether the recipient is worthy or not) and word of murmuring Isaiah 58:9 in benevolence. This is what most men do: they give indeed, but without that readiness, which is a greater and more perfect thing than the mere offering. For he thought it much better to be generous even to the undeserving for the sake of the deserving, than from fear of the undeserving to deprive those who were deserving. And this seems to be the duty of casting our bread upon the waters, Ecclesiastes 11:1 since it will not be swept away or perish in the eyes of the just Investigator, but will arrive yonder where all that is ours is laid up, and will meet with us in due time, even though we think it not.

Citation: Gregory Nazianzus, “Oration 18.” §20 (378)

Gregory’s readiness to give was greater and more perfect than the mere offering itself. More perfect. The mere offering.

If the Roman liturgy was found in the ancient liturgy, then Gregory’s piousness would have been greater and more perfect than the mere offering of the literal body and blood of Christ. This would be absurd.

Of course the Eucharist was not an offering of the body and blood of Jesus. It was offering of tithes, yet for all the many gifts that Gregory gave to the poor, those were mere sacrifices. What mattered was the heart: his willingness and eagerness to give freely.

Yet, only a few years later, after the death of Basil the Great in 379, the Younger Nazianzus would depart from the teachings of the Elder:

Scarcely yet delivered from the pains of my illness, I hasten to you, the guardian of my cure. For the tongue of a priest meditating of the Lord raises the sick. Do then the greater thing in your priestly ministration, and loose the great mass of my sins when you lay hold of the Sacrifice of Resurrection. For your affairs are a care to me waking or sleeping, and you are to me a good plectrum, and have made a well-tuned lyre to dwell within my soul, because by your numerous letters you have trained my soul to science. But, most reverend friend, cease not both to pray and to plead for me when you draw down the Word by your word, when with a bloodless cutting you sever the Body and Blood of the Lord, using your voice for the glaive.

Citation: Gregory Nazianzus (the Younger), “Epistle 171.” (c.383)

And so Gregory described the body and blood of Christ as a sacrifice for the propitiation of sin. Sure, he referred to it as a bloodless sacrifice, and so like his father saw it as symbolic. But, in making Christ’s body and blood a sacrifice, he—along with Amphilochius of Iconium—followed the course originally set in Part 24: Cyril of Jerusalem, who, in 350, also saw this as a symbolic, bloodless sacrificial offering of Christ’s body and blood for the propitiation of sin.