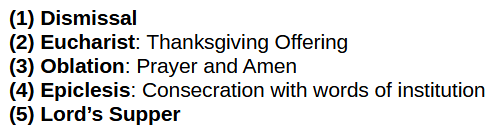

The original liturgy:

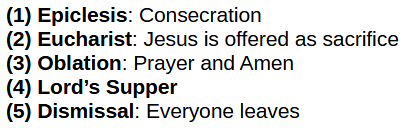

The Roman liturgy:

Cyril of Jerusalem

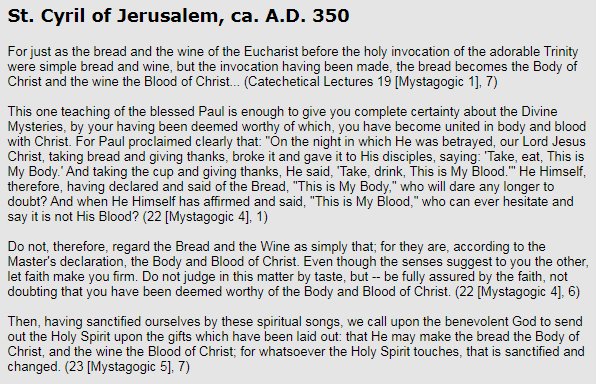

Let’s start with FishEaters’ first quotation. As we’ve done on a number of occasions throughout this series, let’s just complete the sentence:

Citation: Cyril of Jerusalem. “Catechetical Lecture 19.” ¶7 (350)

FishEaters gave this citation to make it appear as if Cyril is arguing for transubstantiation. In reality, he was comparing the holy and profane invocations. The elements of bread and wine offered to Christ were no more Christ’s literal flesh and blood than the meats offered to Satan were Satan’s literal flesh and blood. As we will see below, Cyril viewed the bread and wine as symbols of Christ’s body and blood, just as we’ve seen in the other ancient writings.

In contrasting the holy with the profane, Cyril is not saying that the “simple” bread and wine become the “literal” flesh and blood, he was saying that the “simple” bread and wine—which he calls the thanksgiving—is holy (i.e. not profane) after the consecration.

Let’s go slowly and say that again: the bread and wine (2-3) of the thanksgiving (eucharist) is found before the (4) consecration by the invocation of the words of institution, after which is is holy—consecrated. It is an unconsecrated eucharist before the invocation, it is a consecrated eucharist after the invocation. The consecrated eucharist is no longer common.

But I have made an important error in my analysis, which is revealed by Cyril two lectures later. The invocation is not the epiclesis, it is the oblation.

Citation: Cyril of Jerusalem. “Catechetical Lecture 21.” ¶3 (350)

Cyril references the invocation of the Holy Spirit upon the bread in the same breath as the invocation on the ointment. The thanksgiving offering—eucharist—includes more than the bread and wine: it includes ointment. And the invocation he speaks? It isn’t the words of institution, for he makes no mention of them. It is the (3) oblation of the eucharist. The Holy Spirit is invoked over the entire tithe offering.

Sit and ponder this for a while. Consider the implications of what he is saying. Cyril considered the elements to be consecrated by the Holy Spirit as the body and blood of Christ during the thanskgiving—eucharist—before the words of institution were spoken, for all the elements of the tithe were consecrated together (including the ointment). When Cyril says “invocation”, he is referring to the oblation: the offertory prayer of thanksgiving to God for the tithe.

What Cyril has done is moved the consecration of the bread and wine forward into the oblation without altering the order of the ancient liturgy itself. The invocation over the tithe—the oblation—is now considered to be a consecration. To the best of my knowledge, Cyril, writing in 350, is the first writer to move the consecration from the (4) epiclesis into the (2-3) eucharist and oblation.

Does this sound familiar? In Part 2: The Didache, we noted that Roman Catholics cannot find a consecration in the thanksgiving—eucharist—in the liturgy of The Didache, so they assume that the entire thanksgiving prayer must qualify as a consecration? This idea originates from Cyril, who appears to be the first ancient writer to do this.

We will discuss more about why Cyril made these changes when we discuss Lecture 23 below.

Now, let’s look at the middle two quotes that FishEaters has provided. They are from the same short lecture, so we will quote them together:

Even of itself the teaching of the Blessed Paul is sufficient to give you a full assurance concerning those Divine Mysteries, of which having been deemed worthy, you have become of the same body and blood with Christ. For you have just heard him say distinctly, That our Lord Jesus Christ in the night in which He was betrayed, took bread, and when He had given thanks He broke it, and gave to His disciples, saying, Take, eat, this is My Body: and having taken the cup and given thanks, He said, Take, drink, this is My Blood. Since then He Himself declared and said of the Bread, This is My Body, who shall dare to doubt any longer? And since He has Himself affirmed and said, This is My Blood, who shall ever hesitate, saying, that it is not His blood?

Consider therefore the Bread and the Wine not as bare elements, for they are, according to the Lord’s declaration, the Body and Blood of Christ; for even though sense suggests this to you, yet let faith establish you. Judge not the matter from the taste, but from faith be fully assured without misgiving, that the Body and Blood of Christ have been vouchsafed to you.

Citation: Cyril of Jerusalem. “Catechetical Lecture 22.” ¶1,6 (350)

Wow, the words from Cyril are strongly worded! Who are you to say that the blood of Christ is not his actual literal blood? These are the words of Jesus himself! Cyril had no doubts and neither must you, right?!

Cyril’s words remind me one of the quotes by the Roman Catholic who inspired this series:

Do you find it strange that FishEaters only cited paragraphs 1 and 6? Do you wonder, “What is contained in the context that she left out?” Let’s find out:

He once in Cana of Galilee, turned the water into wine, akin to blood , and is it incredible that He should have turned wine into blood? When called to a bodily marriage, He miraculously wrought that wonderful work; and on the children of the bride-chamber Matthew 9:15, shall He not much rather be acknowledged to have bestowed the fruition of His Body and Blood ?

Wherefore with full assurance let us partake as of the Body and Blood of Christ: for in the figure of Bread is given to you His Body, and in the figure of Wine His Blood; that you by partaking of the Body and Blood of Christ, may be made of the same body and the same blood with Him. For thus we come to bear Christ in us, because His Body and Blood are distributed through our members; thus it is that, according to the blessed Peter,

Christ on a certain occasion discoursing with the Jews said,

They not having heard His saying in a spiritual sense were offended, and went back, supposing that He was inviting them to eat flesh.

In the Old Testament also there was show-bread; but this, as it belonged to the Old Testament, has come to an end; but in the New Testament there is Bread of heaven, and a Cup of salvation, sanctifying soul and body; for as the Bread corresponds to our body, so is the Word appropriate to our soul.

Citation: Cyril of Jerusalem. “Catechetical Lecture 22.” ¶3-4 (350)

Here we again see the ancient liturgy, of the elements figuratively representing the body and blood of Christ as the Word of God. In isolation, FishEaters’ selected quote makes it seem as if Cyril is speaking literally, even as he explicitly states the figurative relationship between the body and the bread. This is not the only time Cyril does this:

…Come, and let us place a beam upon His bread — (and if the Lord reckon you worthy, you shall hereafter learn, that His body according to the Gospel bore the figure of bread;)— Come then, and let us place a beam upon His bread, and cut Him off out of the land of the living;…

Citation: Cyril of Jerusalem. “Catechetical Lecture 12.” ¶19 (350)

When Cyril talks of consuming the bread and wine, he does so in a physical sense. When Cyril talks of the body and blood, he does so in a spiritual sense (soul; divine nature; the Word), clearly noting that the former is the symbol for the later. When one partakes in the physical, they also partake in the spiritual. Cyril keeps his categories distinctly separate: the bread is for the body, the Word is for the soul.

Now, let’s do this again, but this time something different will take place. In FishEaters’ final quotation, she cites this paragraph:

Citation: Cyril of Jerusalem. “Catechetical Lecture 23.” ¶7 (350)

Let’s look at what she left out:

Then, after the spiritual sacrifice, the bloodless service, is completed, over that sacrifice of propitiation we entreat God for the common peace of the Churches, for the welfare of the world ; for kings; for soldiers and allies; for the sick; for the afflicted; and, in a word, for all who stand in need of succour we all pray and offer this sacrifice.

Then we commemorate also those who have fallen asleep before us, first Patriarchs, Prophets, Apostles, Martyrs, that at their prayers and intercessions God would receive our petition. Then on behalf also of the Holy Fathers and Bishops who have fallen asleep before us, and in a word of all who in past years have fallen asleep among us, believing that it will be a very great benefit to the souls , for whom the supplication is put up, while that holy and most awful sacrifice is set forth.

And I wish to persuade you by an illustration. For I know that many say, what is a soul profited, which departs from this world either with sins, or without sins, if it be commemorated in the prayer? For if a king were to banish certain who had given him offense, and then those who belong to them should weave a crown and offer it to him on behalf of those under punishment, would he not grant a remission of their penalties? In the same way we, when we offer to Him our supplications for those who have fallen asleep, though they be sinners, weave no crown, but offer up Christ sacrificed for our sins , propitiating our merciful God for them as well as for ourselves.

After this ye hear the chanter inviting you with a sacred melody to the communion of the Holy Mysteries, and saying, O taste and see that the Lord is good. Trust not the judgment to your bodily palate no, but to faith unfaltering; for they who taste are bidden to taste, not bread and wine, but the anti-typical Body and Blood of Christ.

Citation: Cyril of Jerusalem. “Catechetical Lecture 23.” ¶8,9,10,20 (350)

In paragraphs 8 and 10, we find the answer to the riddle that we found in Lectures 19 and 21: why did Cyril make the oblation of the thanskgiving tithe—the eucharist—a consecration? Because in doing so, he became the first writer to offer the body and blood of Christ as a propitiatory sacrifice.

Instead of offering their thanksgiving to God and giving their tithes to the poor, the Church was now going to offer propitiation for sin.

Sure, Cyril still viewed the body and blood of Christ as figurative (thus, bloodless) symbols (not transubstantiation). Here he explicitly calls them “anti-typical” (or symbolic). He didn’t alter the order of the ancient liturgy and the thanksgiving still included tithes other than bread and wine. But, Cyril now considered the oblation—rather than the epiclesis—to consecrate the bread and wine being offered as a sacrifice. In changing the meaning of the liturgy without changing its structure, Cyril turned the bread and wine into body and blood of Christ for a sacrificial propitiation for sin during the thanksgiving prayer.

This was a monumental pole shift in the history of the liturgy. The impact of this cannot be overstated. It truly set the foundation for the rise of Roman Catholicism and its Mass sacrifice.

It is especially notable that Cyril’s novelty of offering the body and blood as propitiation for sin is associated with another heresy. In paragraph 9 and 10, he advocates prayers for the dead. Notice how he anticipates objections to his novelty. But these are not the only novelties that Cyril attempted to add to the practices of the church.

In approaching therefore, come not with your wrists extended, or your fingers spread; but make your left hand a throne for the right, as for that which is to receive a King. And having hollowed your palm, receive the Body of Christ, saying over it, Amen. So then after having carefully hallowed your eyes by the touch of the Holy Body, partake of it; giving heed lest you lose any portion thereof ; for whatever you lose, is evidently a loss to you as it were from one of your own members. For tell me, if any one gave you grains of gold, would you not hold them with all carefulness, being on your guard against losing any of them, and suffering loss? Will you not then much more carefully keep watch, that not a crumb fall from you of what is more precious than gold and precious stones?

Then after you have partaken of the Body of Christ, draw near also to the Cup of His Blood; not stretching forth your hands, but bending , and saying with an air of worship and reverence, Amen , hallow yourself by partaking also of the Blood of Christ. And while the moisture is still upon your lips, touch it with your hands, and hallow your eyes and brow and the other organs of sense. Then wait for the prayer, and give thanks unto God, who has accounted you worthy of so great mysteries.

Citation: Cyril of Jerusalem. “Catechetical Lecture 23.” ¶21-22 (350)

In paragraphs 21 and 22, Cyril is telling those who will receive communion for the first time how to show a properly reverent mode of conduct. He instructs them in how to receive the bread—by cupping their hands so they don’t drop it—and how to drink from the cup—by leaning down and forward to the cup rather than trying to draw the cup up to their lips (this “bending” is sometimes misinterpreted as an instruction to bow before the wine….and only the wine). But then Cyril tells them what to do with the wine:

…while the moisture is still upon your lips, touch it with your hands, and hallow your eyes and brow and the other organs of sense.

That’s right, take that bread and wine—which is the body and blood of Christ—place a little bit of the wine from your lips onto your fingers or the bread from you hands and then touch them to your face: eyes, brows, ears, mouth, lips, nose, and skin.

Such actions would utterly horrify the Roman Catholic. And it does! So absurd are Cyril’s novelties in Lecture 23, that some Roman Catholics conclude that it must not have been written by Cyril (thanks to Tim Kauffman for these references):

Citation: Receiving Communion on the Hand is Contrary to Tradition, The Catholic Voice, 2001

Citation: Jude Huntz, Rethinking Communion in the Hand, parentheses in original

Citation: The great Catholic horror story: the pseudo-historical deception of Communion in the hand

I too wish that Cyril’s words were not actually Cyril’s own words, as they represent a significant deviation from the ancient liturgy. I wish I could cry out “Fake! Fake! Fake!” But as we showed in Lectures 19 and 21, Cyril’s views of the sacrifice of propitiation are explained by Lecture 23. The ancient liturgists would not have liked Cyril’s corruption of the ancient liturgy either. Nor did his own congregants appreciate the changes he was trying to persuade them to accept. But, personally disliking his viewpoints is not a valid reason to declare his writings unauthentic, especially when those writings are consistent with each other.

Roman Catholics like that Cyril advocated prayers for the dead. They like that Cyril moved the consecration of the bread and wine into the Eucharist. But they have problems with a lot of other things Cyril wrote, like how congregants should handle the communion bread. But, intellectual honesty means you don’t just cherry-pick what you agree with and ignore the rest. Cyril was no Roman Catholic who subscribed to the Roman liturgy. He didn’t believe in transubstantiation, for example.

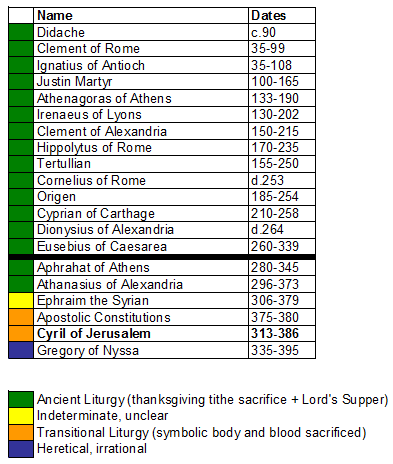

But, while Cyril—writing just a bit more than 300 years after the ascension of Christ—affirmed much of what we’ve seen throughout this series as part of the ancient liturgy, you can also see how his views began a developmental shift to what would one day be established as the Roman liturgy in the 6th or 7th century.

Many times throughout this series—The Didache, Justin Martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Origen, Cyprian, Aphrahat, Athanasius, Eusebius, Lactantius—we have noted that the ancient church viewed the thanksgiving—eucharist—as the sacrificial fulfillment of Malachi 1:11. All of these described the ancient liturgy. But what about Cyril?

Of old the Psalmist sang,

But after the Jews for the plots which they made against the Saviour were cast away from His grace, the Saviour built out of the Gentiles a second Holy Church, the Church of us Christians, concerning which he said to Peter,

And David prophesying of both these, said plainly of the first which was rejected,

but of the second which is built up he says in the same Psalm,

and immediately afterwards,

For now that the one Church in Judæa is cast off, the Churches of Christ are increased over all the world; and of them it is said in the Psalms,

Agreeably to which the prophet also said to the Jews,

and immediately afterwards,

Concerning this Holy Catholic Church Paul writes to Timothy,

Citation: Cyril of Jerusalem. “Catechetical Lecture 18.” ¶25 (350)

What does Cyril identify as the incense and sacrifice that the Church offers to God? It is blessings, praise, and glorifying God.

This is remarkable. Even though Cyril has begun to sacrifice Christ’s body and blood, albeit symbolically, he still views the prophesy of Malachi as being fulfilled in the blessings, praises, and glory that the church brings to God. Given the clear chance to confirm the Roman liturgy by saying…

…he chooses not to! Thus, even in the midst of his doctrinal innovation, he still maintains the ancient meaning of Malachi’s prophesy.

The prophecy of Malachi is that God would replace the Jews and their corporeal sacrifices with a Church made up of Gentiles and their incorporeal sacrifices. God was bragging to—and threatening—the Jews about his replacement upgraded followers and their replacement upgraded sacrifices. God’s new followers would be superior to the old because they would love him with their hearts.

This is why the greatest commandment is “Love the Lord your God.” The fulfillment of Malachi meant that no longer were sacrifices required for sin, for Christ was the final sacrifice. Now the only sacrifice was the circumcision of the heart: to love God freely and fully, to offer him one’s joyful praise and thanksgiving.

This reads remarkably like Malachi’s prophecy. The Jews are defiling and defaming God with their evil deeds (again!). God wants to be great among the nations. To do this, he needs followers with pure hearts and the sacrifices of praise.

It makes no sense for Cyril to insert Christ’s sacrifice into Malachi, and so he doesn’t. It probably never even occurred to him.

Pingback: Justification by Faith, Part 1

Pingback: Too Slow To React In Time - Derek L. Ramsey

I wrote this:

Well it turns out that I identified this same starting point as did scholar J.N.D. Kelly. He, notably, cites the same sources that I cited above.

(5) Cat. 22, 9; 23, 20.

(6) lb. 22, 3.”

— J.N.D. Kelly, “Early Christian Doctrines.” Fourth Edition (1968). page 441.

Here is what Philip Schaff wrote of the distinctly pre-Roman liturgy.

The communion was a regular and the most solemn part of the Sunday worship; or it was the worship of God in the stricter sense, in which none but full members of the church could engage. In many places and by many Christians it was celebrated even daily, after apostolic precedent, and according to the very common mystical interpretation of the fourth petition of the Lord’s prayer. The service began, after the dismission of the catechumens, with the kiss of peace, given by the men to men, and by the women to women, in token of mutual recognition as members of one redeemed family in the midst of a heartless and loveless world. It was based upon apostolic precedent, and is characteristic of the childlike simplicity, and love and joy of the early Christians. The service proper consisted of two principal acts : the oblation or presenting of the offerings of the congregation by the deacons for the ordinance itself, and for the benefit of the clergy and the poor; and the communion, or partaking of the consecrated elements. In the oblation the congregation at the same time presented itself as a living thank-offering ; as in the communion it appropriated anew in faith the sacrifice of Christ, and united itself anew with its Head. Both acts were accompanied and consecrated by prayer and songs of praise.

— Philip Schaff, “History of the Christian Church.” Volume 2 (1922). Pages 236-237.