This is part of a series on patriarchy, headship, and submission. See this index.

Agency in the Greek Language

In my post, “On Divorce,” I briefly discussed how the biblical Greek language handles men and women differently when it came to certain moral actions. The cultural notions of agency are built right into the linguistic structure of the language. For example, in biblical Greek you would say…

a man marries while a woman gets married[1]

a man divorces while a woman gets divorced[2]

a man fornicates while a woman gets fornicated

a man commits adultery while a woman gets adulterated[2]

a man submits while a woman gets submitted[3]

…regardless of who—man or woman—was the causal actor, the moral agent, or the person responsible for the action. In general, linguistically,

a man acts, while a woman is acted upon.

If a Hebrew woman marched down to the synagogue and got a divorce certificate, her Greek-speaking neighbors could say of her husband “he divorced his wife” and of her “she got divorced” and be correct on both counts. In Greek, the language carries the presumption of the man being the casual actor, regardless of who had actual agency, authority, or responsibility. From the Greek language alone, we don’t know initiated the divorce. It could have been the man, the woman, or both of them in mutual agreement. The response of the neighbors would be correct in all three possibilities.

The English language does not work this way, so when we hear “he divorced his wife”, we know that he filed the papers or was responsible—at fault—for the divorce taking place (e.g. having an affair). If it wasn’t his responsibility or we wanted to blame the wife, we would simply say “she divorced her husband.”

It is a mistake of language to read the English-from-Greek translation of gendered language as if it confers sole authority, responsibility, and agency upon men and men alone. That’s not how the language works. These linguistic structures reflect the culture in which they are derived, but they do not prescribe upon it.

A clear example of this is found in the Book of Sirach 23:22-23, where a woman is unfaithful to her husband. She was a whore who committed adultery against her husband and had a child with another man. The context is completely unambiguous that she was the responsible agent. Even so, the Greek linguistics do not say that she committed adultery (i.e. the active voice), rather, the gendered language of indirect agency (i.e. the middle voice) matches her sex.

Who can Submit?

The Greek linguistic convention is found in Paul’s use of submission. Consider this paraphrasing of Ephesians 5:

Husbands and Wives, be filled with the Spirit by…

…submitting yourselves to each another out of respect for Christ;

Wives to your husbands as to Christ,

because the husband is the head of the wife just as Christ our head, having died for us (his body).

But as we submit to Christ, so wives to their husbands in everything

The wife is to respect her husband

Husbands love your wives, as Christ demonstrated God’s love by dying for us While we were still sinners

Husbands love your wives, as you love yourself and your body, nourishing and tenderly caring for it, as Christ cares for for us.

Because husbands and wives are one body.

Because the church is one body with Christ.

Paul does not use any active imperatives—commands—when speaking only to wives. When speaking to both husbands and wives, he uses the same oblique, non-imperative manner[4]. But when he addresses husbands individually, he does so directly, actively, and imperatively: to love sacrificially. This reflects the linguistic convention that only men can be the perpetrator or acting agent, even when women have agency (e.g. divorce). Even the English translations make this reasonably clear if one looks for it.

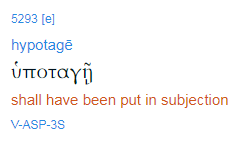

Only men can be told to submit, so women cannot be given the imperative to submit, as the language conventions do not allow it. Thus, when Paul tells wives to “[be] submitting” (middle voice) and husbands to “love” (active voice) after telling both husbands and wives to “[be] submitting” (middle voice) to each other, this active/middle distinction doesn’t—on its own—imply anything about the agency or authority of the husbands and wives involved. Whether or not women or men submit has nothing to do with this simple language convention.

Paul Instructs Men

So how do we know if Paul wants husbands to submit to their wives, wives submit to their husbands, or wives and husbands to submit to each other? Who has agency here? The answer is simple. It isn’t found in the language construct, but in the context:

Paul wasn’t telling husbands to simply act in accordance with the Household Codes, as rulers of their families. Rather, he told men to (in this sequence):

Ironically, Paul successfully conveys his instruction that men submit to their wives—by their culturally debasing sacrificial love—using the Greek language convention of the men being the active agents. After all, only men have the agency to actively submit! This makes perfect sense to a Greek-speaker, but to the English-speaker this is nearly gibberish.

Submission isn’t Active

In biblical Greek, since only men are told to submit, women cannot be given the imperative to submit, as the conventions do not allow it. Paul never uses submission—nor authority or rule—in an active imperative. Neither Paul—here or in Colossians 3:18 and Titus 2:5—nor Peter—in 1 Peter 3:1—ever use an active imperative to instruct wives—or husbands—to submit, including when discussing mutual submission.

Most importantly, Paul does not use the active voice to describe any submission: whether of wives submitting to their husbands, husbands to their wives, or husbands and wives to each other. The consistent use of the middle voice shows that ‘submission’ of husbands and wives—which is mutual and bidirectional—implies respect or deference[5], not rule and obedience.

Now we delve into the biggest problem with understanding what Paul is saying. While Greek-language conventions do not allow women to be given the imperative to submit, English-language conventions require it. In English, you can’t easily avoid the active imperative. The implied meaning of the English verb ‘submit’ is effectively always active and imperative.

The active voice is defined as…

the subject is the doer of the action

…while the middle voice is defined as:

the subject is the doer of the action, but they receive the action at the same time.

Consider the three forms:

active voice (intransitive): The wife submits to her husband

active voice (transitive): The wife submits her husband

passive voice: The wife is submitted to her husband

middle voice: The wife submits herself to her husband

In English, it is easy for the word submit to lose its intended meaning if it isn’t worded properly: “The wife submits her husband” and “The wife is submitted to her husband” have a completely different meaning than “The wife submits to her husband”. A different English word or phrase has to be used in these forms.

Similarly, it is difficult to construct a valid middle voice example, a hybrid of the active and passive, because of this meaning changes in the passive. How can the wife, in “the wife submits herself”, passively receive the action she is actively doing? To eliminate any hint of the wife handing herself over like a piece of mail, as in the above examples, the phrase “the wife submits herself to her husband” is functionally reduced to the active “the wife submits to her husband” without changing its meaning at all! But this is precisely what most English readers do when they read Ephesians 5.

A true middle voice statement….

I killed myself for my wife

…cannot be reduced to the active form…

I killed for my wife

…and retain the same meaning. Here the middle and active forms have very different meanings, as they should.

The English ‘submit’—when referring to subjection or yielding to authority—is effectively an intransitive verb, but verbs in English must be transitive to be in the middle voice. The closer you get to submit being a transitive verb, the more it sounds like “The wife submitted her husband to the mailbox.” Submission—as subjection in the English middle voice form—is simply a verbose alternative way of using the active form. The typical English reader will always interpret the English word “submit” in the active voice.

See, unlike English, in Greek an intransitive verb can be used in the middle voice. Consequently, the only translation choice available in English is to translate a Greek word—that in English is intransitive—into English using the active voice. Thus, the translation from Greek middle voice into English is going to be error-prone, especially if the word is intransitive in English, because it loses the middle force.

Submission in English is more-or-less always an active imperative. Submission—by Paul—is not. That is why what Paul is saying sounds like gibberish to the English speaker, but it is anything but that.

At the end of the day, the English speaker cannot rely on his common understanding of the archaic word ‘submit’ to guide him in understanding of what Paul is saying. Paul’s idea of submission is one of love and respect, not subordination:

Cultural Context

The cultural context of the book of Ephesians is critical to understand its meaning. Gordon Fee notes:

What truly set everyone’s teeth on edge is that Paul was altering the basis of the relationship between husband and wife from one of power to one of love and respect, without altering the cultural framework or abolishing the Roman Law upon which the family was based. Both the loving service of the husband to his wife and the submission and respect of the wife to her husband became a matter of serving the Lord, not obedience to the Roman law.

Footnotes

[1] “The distinction [..] is an important example of Greek active versus mediopassive voice [..] This is also a good example of how gendered difference in agency and personhood is structured into basic linguistic distinctions. As I teach my students, the middle voice is often about indirect agency (when the agent of an action is not the same as the grammatical subject of the sentence).” — Sententiaeantiquae, “A Man Married, a Woman Gets Married.” (2018-11-30)

[2] “[E]ven when the woman is construed as an explicit agent in the event, the one who is responsible for her actions, the pattern holds. Consider, for instance, verbs of divorce & adultery [..] Men who divorce are: ὁ ἀπολύων, but women who divorce are ἡ ἀπολυθεῖσα. [..] To begin, the law assumes a male perpetrator: a person who commits adultery with the wife of a man, or the wife of a neighbor. But the event structure [of Leviticus 20:10] assumes a reciprocity of the action between the two adulterers. Both occurrences of μοιχεύσηται may be considered reciprocal uses of the middle; adultery is an act committed with someone. Notice, however, a shift in voice in the latter portion of the verse that occurs alongside a shift in the gender of the referents. The male perpetrator is expressed as active (ὁ μοιχεύων). The female perpetrator is expressed as middle (ἡ μοιχευομένη).” — Rachel Aubrey, “Gender & voice: marriage, divorce, adultery.” (2018-12-03)

[3] In English we do not say someone “gets submitted by” or “is submitted to.” If we want to say it passively, we might say “is subjected to”, but then we are no longer using the word “submit” and “subjected” is a more explicitly subordinate form of submission. In English, the word “submit” nearly always carries an active sense, so it is very difficult to translate the Greek middle voice into English. It is very difficult to translate submission at all from Greek to English:

[4] The only active imperative applied to both husbands and wives is “be filled.” Mike Aubrey notes that in the case of an elided verb, the ellipsis does not function to transfer the imperative sense (emphasis added):

He further notes:

[5] Mike Aubrey also notes that the English term ‘submission’ is archaic and should not be used.

Pingback: "It's a Military Term"

Pingback: Mutual Submission

Pingback: Mutual Submission, Part 6