This is part of a series on patriarchy, headship, and submission. See this index.

Note: this version of the essay was updated based on feedback received.

A Question

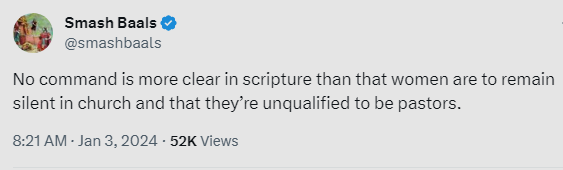

A while back, while was I was debating “Headship: Authority or Preeminence?” at the Sigma Frame blog, a couple readers were discussing it over a Deep Strength’s blog. One commenter asked an excellent question:

— comment @ Deep Strength, “Torturous logic on divorce and complementarian trashology“

To the first question, it doesn’t really matter if people think women should be silent in churches. There is some evidence to think that, indeed, there was a tradition of women and children sitting quietly and separately from the men in some early congregations. But tradition isn’t doctrine. We need to know that our doctrines are rooted in dogmatic truth of the Word of God, and not merely based on non-binding traditions that are subject to personal conviction. If women are kept silent as a matter of false doctrine, then that is a grave sin we should all be concerned about. This is why I would subject the passage to a critical examination, to know for sure one way or the other.

Recall the list of patriarchal passages in the New Testament given in “Headship: An Evidence Summary“:

- 1 Corinthians 11:1-15

- 1 Corinthians 14:34-35

- Ephesians 5:22-33

- 1 Peter 3:1

- Colossians 3:18-19

- 1 Tim 2:11-15

- Titus 2:3-5

In the evidence summary, I argued that the support for Headship from the New Testament is not particularly strong. It relies mostly on extra-biblical context to justify the particular interpretation, that is, eisegesis. Headship needs every bit of biblical evidence it can get, so each and every one of the patriarchal proof-texts is important. Therein lies the problem: it is good biblical hermeneutics not to base essential doctrines on a small selection of contested proof-texts.

Forgeries

According to many scholars—a mix of atheists, agnostics, and even some Christians—who study the origins of the books of the Bible, both 1 Timothy and Titus are considered forgeries. The term for works where the author claimed is not the one writing is pseudoepigrapha, and includes dozens of works not considered canonical by Christianity. Few textual critics—as distinct from theologians[1]—believe Timothy and Titus were written by their stated authors, that is, the authors lied, passing themselves off as someone else.[2]

Worst case, if 1 Corinthians 14:34-35 is a forgery—and there is strong reason to think it, like the Pericope Adulterae, is not original but a selective insertion into the original—then along with 1 Timothy and Titus being forgeries, 43% or 3 of the 7 patriarchal passages not only wouldn’t count as evidence of Headship, but would be evidence of doctrinal development, evidence against headship.[3]

Regardless of what you will ultimately conclude about their authenticity (or the people making the claims), it is important to examine the issue in order to get it right.

The scope of this article is not to lay out the complexities of arguments that any of these patriarchal passages are in fact forgeries, but to answer the preliminary question, “What’s the point of questioning it?” The answer is simple. If, and I mean *if*, one or more passages of significance are forgeries, then it greatly matters to whether Headship is a valid doctrine. One must be very careful before pushing a contested doctrine based in large part on possible forgeries.[4]

The Problem

It concerns me how heavily Headship doctrine appears to rely on (1) what may possibly have been an attempt by dishonest forgers to create a false doctrine where none previously existed[5] and (2) based on traditionally difficult to understand passages[6] that few theologians can agree on, even when they agree on doctrine. Without the support of the potentially contested patriarchal passages, you are left with the uncontested passages[7] Ephesians 5:21-33, 1 Peter 3:1, and Colossians 3:18-19, which together describe mutual submission, not headship.[8][9]

I’ve never argued that Timothy or Titus are actual forgeries because I don’t find the evidence of Christianity’s enemies to be convincing. I’ve only argued, here, that 1 Corinthians 14:34-35 is questionable. The primary reason to be concerned about 1 Corinthians 14:33-34 is because it creates an apparent contradiction[10] with 1 Timothy 2:11-15 and in doing so calls into question the authenticity of all of the Pastoral Epistles.

1 Corinthians was written first and much earlier, when Timothy was the traveling companion of Paul. If Paul had taught in every church he visited the universal principle that women could not speak in churches for any reason at all, then why would Paul have needed to tell Timothy in Ephesus a decade later that a woman could not teach? If she isn’t allowed to speak at all, how could she be teaching, let alone teaching a man? It makes no sense at all.[11] This opens the door for non-Christians—such as Bart Ehrman—to come in and say that the Pastoral Epistles are forgeries, because it couldn’t possibly be Paul writing the letters.

By insisting that 1 Corinthians 14:33-34 is authentic[12], when the evidence weighs against it, it potentially harms the perceived authenticity of the rest of the Bible to seekers and the enemies of Christ alike. Since all scholars agree that 1 Corinthians was written by Paul, treating 1 Corinthians 14:33-34 as if it was equally attested to the rest of the letter only adds credence to the claim that Timothy and the rest of the Pastoral Epistles are forgeries.

Were it not for the Headship doctrine, scholars and theologians would be far more likely to treat 1 Corinthians 14:33-34 as a non-scriptural scribal gloss that got (accidentally?) inserted and argue that it should be removed. Presuppositional adherence to a particular doctrine is not a good reason to declare that something isn’t a forgery. Indeed, such eisegesis begs-the-question.

Were any of the contested passages[5] contested because they represent some core truth that the enemies of Christ wish to obfuscate? Were they added in by enemies of Christ in order to obfuscate and change the roles that Christ intended for husbands and wives in the church? These are important questions. Examining the passage is only uninteresting and irrelevant to those who hold an axiom that makes such questions invalid.

Side Note

Consider the implied question…

Footnotes

[1] The axiom of sola scriptura states that scripture alone is the Word of God revealed to men. Implicit in this is some sort of axiomatic claim to the authenticity of scripture as contained in the categories of inspiration, preservation, and accessibility. How these interact differs among Christians and denominations. The distinction from between scholars (e.g. textual critics) and theologians is that the question of inspiration, preservation, and accessibility is mostly in the realm of theology: if one axiomatically holds that 1 Timothy and Titus are the inspired and inerrant Word of God, then it doesn’t matter what scholarship says.

[2] This was not, as some would claim, a commonly accepted practice. Paul himself complained about another writing letters in his name.

[3] Theologians who axiomatically accept 1 Timothy and Titus won’t care, but if a seeker doesn’t believe in the particular form of sola scriptura (which also includes the Orthodox and Roman Catholics), then they will need to be convinced of that long before the topic of Headship becomes relevant.

[4] Unless your axiom is that “the Bible canon is defined by X” and that accepting this axiom is a prerequisite for belief in Jesus Christ and for salvation.

[5] 1 Corinthians 14:34-35, 1 Tim 2:11-15, Titus 2:3-5

[6] 1 Corinthians 11:1-15, 1 Tim 2:11-15

[7] Both by historical scholars and textual critics (as to their authenticity) and theologians (general agreement as to their exegesis). Ephesians and Colossians are not truly “uncontested”, as they are included in the “possibly authentic” works of Paul. I’ve not see enough conclusive evidence one way or the other, so I do not find it relevant enough to be more than a footnote.

[8] In case anyone thinks I’m bringing up the academics calling those letters forgeries because I want them removed from the Bible, the reality is that I don’t think the inclusion or exclusion of the “forged” letters has any impact on mutual submission as a biblical doctrine, but those who argue for Headship seem to rely on them.

[9] Since 1 Corinthians is an undisputed work of Paul, any doctrines that come out of it should be supported by all Christians, but if 1 Corinthians 14:34-35 itself is forged, and exegetes can’t agree on the meaning of 1 Corinthians 11:1-15 because the language and phrasing is so obscure, then the accepted authenticity of the work as a whole doesn’t matter.

[10] It also creates an apparent contradiction with 1 Corinthians 7:8.

[11] Nor do all the various references to women taking leadership roles in the church.

[12] Because of the apparent contradiction with 1 Timothy and the rest of 1 Corinthians, some have suggested the the contested is an authentic quotation that Paul is arguing against.

Pingback: Lying to Combat Lying

Pingback: 1 Corinthians 14:34-35