Sometimes I feel as if I’m living in a parallel universe from others. I wrote this article months ago, but had not yet scheduled it for publication. Then, just yesterday, I read Bruce Charlton’s “Necessity does not obviate the requirement for repentance” and I once again got that weird feeling. He wrote:

As we will see below, what is especially disorienting about this is that Charlton’s theology is deeply based on the 4th Gospel, the Gospel of John. You’ll see why it is so disorienting shortly.

In our 13-part series “On Forgiveness” earlier this year, we discussed how faith—not repentance—led to forgiveness. But I wanted to discuss repentance in more detail, but many Christians are simply unaware how the Bible treats the topic compared to what they have learned about in their churches and from other Christians. Even non-traditional Christians—like Charlton—are still writing about repentance!

The New Testament uses two words to refer to repentance in the New Testament, the verb metanoeó (μετανοέω) and the noun metanoia (μετάνοια). Here I will introduce the idea of repentance in the New Testament.

I had originally wanted make a series out of this topic by examining the each use of the words in their contexts, but I no longer want to hold up this post. I may, in the future, revisit this topic. Let me know in the comments if a follow-up series would interest you.

Review

It’s been a while, so before we begin, let’s have a quick review of the last time we discussed repentance in “On Forgiveness, Part 12.”

As noted throughout this series (especially Part 5) and in the comments, repentance and sacrifice were closely linked in the Old Covenant. As I noted in Part 11, John the Baptist taught repentance and baptism for the forgiveness of sins. But once Jesus came, what mattered most was faith. Paul explained:

Under the Old Covenant, repentance was the only option available for the forgiveness of sins. But, in the New Covenant, Jesus offered something different.

Consider rereading Part 5, which adds substantial context to what follows.

Usage

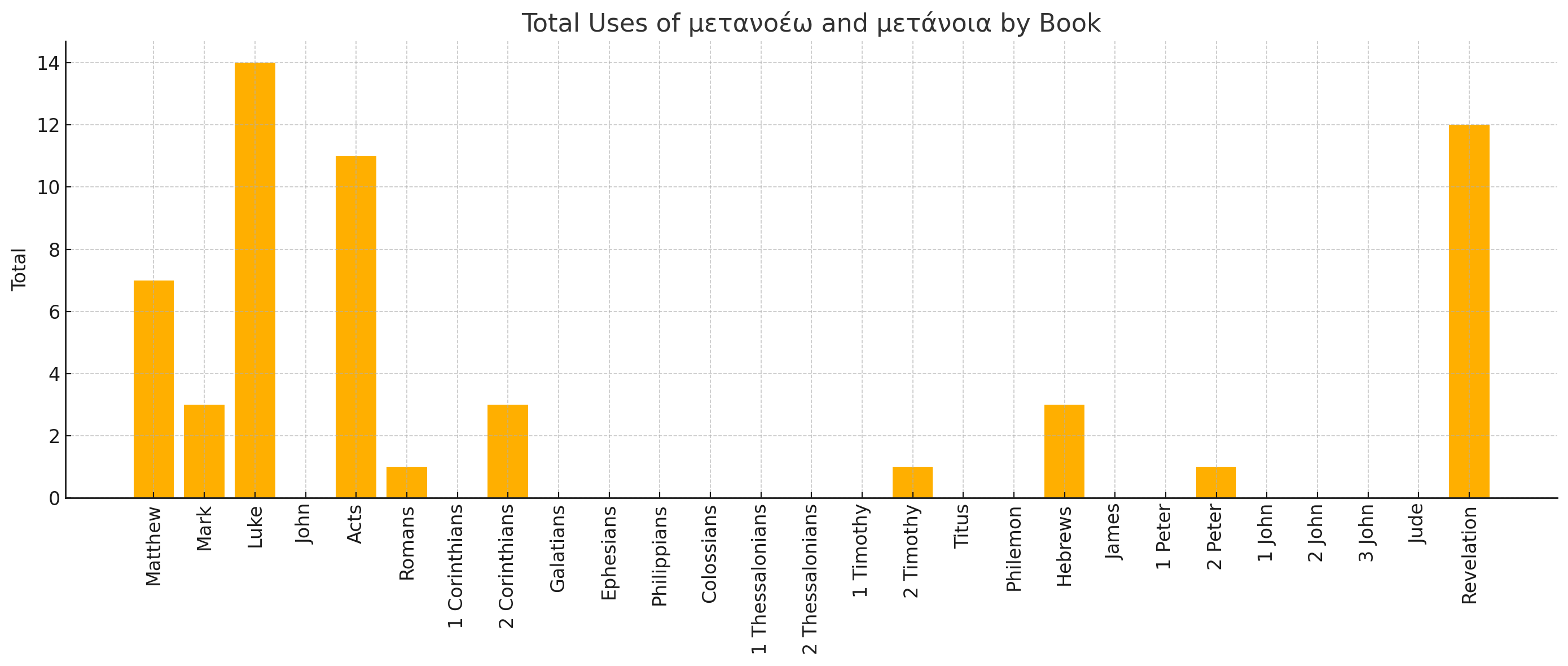

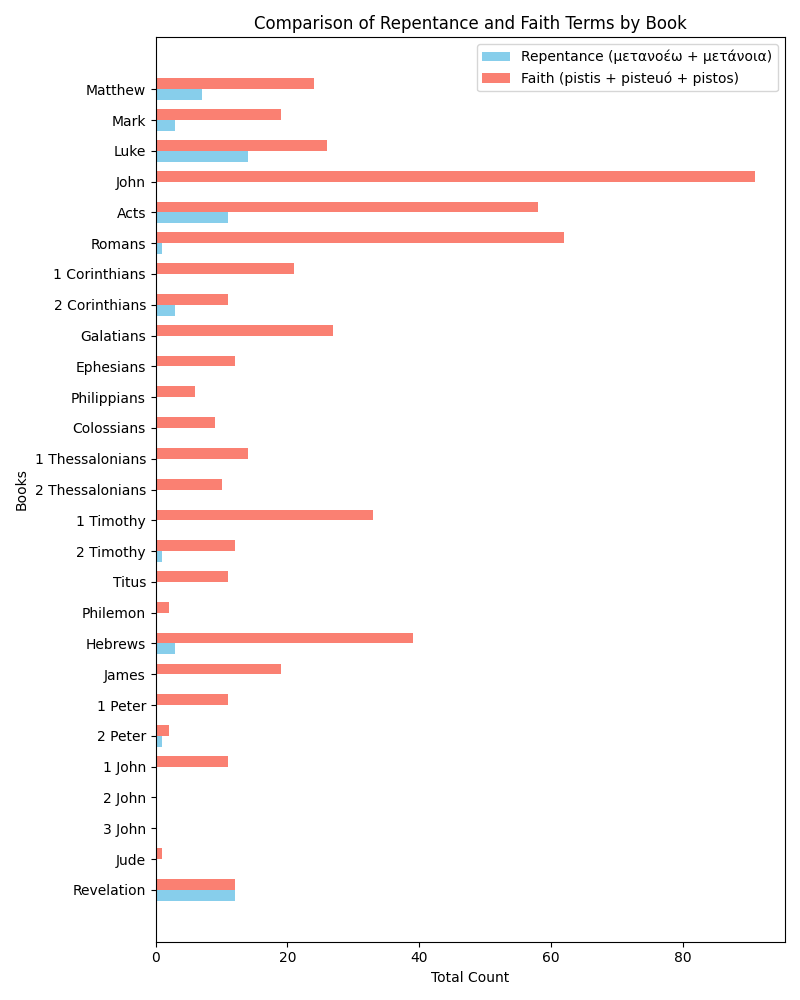

In the New Testament, the verb form of repentance is used 34 times and the noun form is used 22 times, for a total of 56 total references to repentance. This may seem like a lot, but it really isn’t. We will illustrate this in five different ways.

First, let’s look at the distribution for how repentance is used.

| Book | μετανοέω (metanoeó) | μετάνοια (metanoia) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matthew | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| Mark | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Luke | 9 | 5 | 14 |

| John | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Acts | 5 | 6 | 11 |

| Romans | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 Corinthians | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 Corinthians | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Galatians | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ephesians | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Philippians | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Colossians | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 Thessalonians | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 Thessalonians | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 Timothy | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 Timothy | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Titus | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Philemon | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hebrews | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| James | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 Peter | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 Peter | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 John | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 John | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 John | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Jude | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Revelation | 12 | 0 | 12 |

Here is a histogram of that same data:

Were you aware that 17 books of the New Testament don’t even mention repentance at all, including one of the Gospels (the 4th one)? In his letters, Paul only mentions repentance once in Romans, three times in 2 Corinthians, and once in 2 Timothy. The only authors who seem to be highly concerned with repentance are Luke (in Luke and Acts) and John the Revelator (in Revelation).

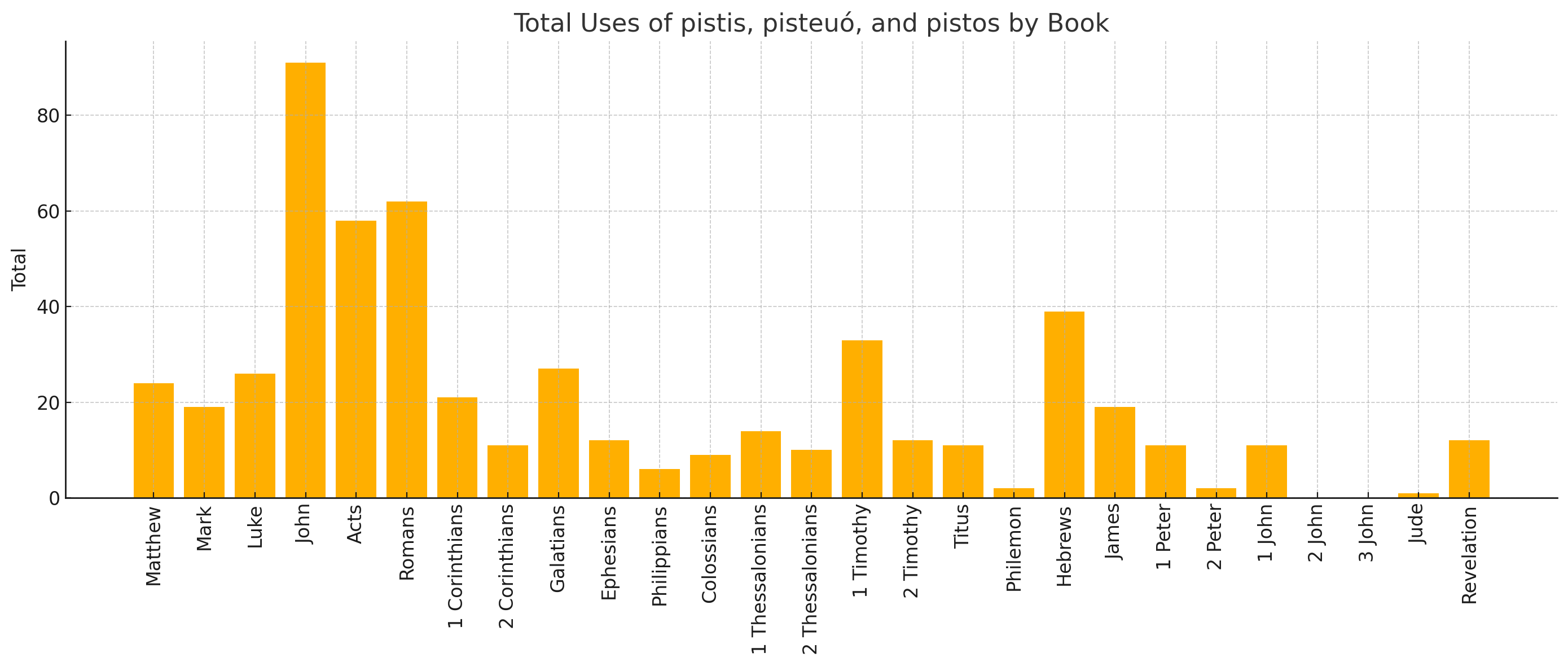

Second, let’s compare this to the three main words for faith (that is, belief and trust):

- faith, noun — pistis — 243 times

- believe, verb — pisteuó — 244 times

- faithful, adjective — pistos — 67 times

That’s a total of 554 references to faith, an astounding ten times greater number of references compared with repentance. And, unlike repentance, faith is mentioned in nearly every book of the New Testament. It is a core theme of many of them, especially the 4th gospel, the Gospel of John:

The difference in emphasis between faith and repentance is stark:

Third, in the Old Testament the word for repentance is shuwb (שׁוּב). It is mentioned a total of 1,056 times. But the primary words for faith in Hebrew (emuwnah and aman) occur less than 200 times.

Fourth, the Greek words for repentance in the New Testament were used only once in the Greek Septuagint. When the New Testament writers wanted to talk about repentance, they did so in a way that differed from the Greek Old Testament. The Septuagint used the Greek word epistrephó instead, a word used only 36 times in the New Testament, and often to describe physically turning around or returning. Of these…

| Book | ἐπιστρέφω (epistrephó) | Possibly meaning “repent” |

|---|---|---|

| Matthew | 4 | |

| Mark | 4 | 1 |

| Luke | 7 | 4 |

| John | 1 | |

| Acts | 11 | 8 |

| 2 Corinthians | 1 | 1 |

| Galatians | 1 | |

| 1 Thessalonians | 1 | 1 |

| James | 2 | 2 |

| 1 Peter | 1 | 1 |

| 2 Peter | 1 | |

| Revelation | 2 |

…only a few could possibly be translated as repent, although this rarely occurs in English translations. The bulk of these are, again, restricted to Luke (in Luke and Acts). For example, here is what happens if you translate it as repent alongside the other word for repent:

This makes the irony even more intense.

Fifth, none of the New Testament letters known for sure to be written after 70AD and the fall of Jerusalem (marking the end of the Old Covenant) mention repentance. The only oddity in the New Testament is Matthew, which discusses repentance yet was written after 70AD. But, of course, everything recounted there is a retelling of what took place before 70AD.

If the date of publication is a valid indication, the apostles were no longer talking about repentance after the fall of Jerusalem (not that they were discussing it all that much prior).

A Point of Emphasis

In the Old Testament, repentance is very important, much more important than faith. The opposite is true of the New Testament. An examination of all 56 references to repentance in the New Testament will show that with Jesus, something very important had changed. As we saw in “On Forgiveness, Part 12,” repentance was the central feature of the Old Covenant, while faith is the central feature of the New Covenant.

The point of all of this is not to say that repentance is unimportant or irrelevant. It is not the claim that repentance is optional either. Rather, it is observation that repentance was the only thing available for temporary and conditional forgiveness under the Old Covenant, but that Jesus brought something greater that provided permanent and unconditional forgiveness under a New Covenant.

The writers of the New Testament didn’t have to spend time talking about repentance, because they knew that true faith in Christ produced the fruit of repentance. The proof of faith in Christ is displayed by the changes and outputs of the way one live’s their life. Repentance is the result of faith, not its cause.

Thus did almost all of the New Testament writers focus primarily on faith. In some cases, they did so to the complete exclusion of repentance. Indeed, I would suggest that the New Testament concept of sanctification has subsumed—and thus replaced—repentance. Repentance didn’t go away, exactly, it just became something else, something greater and more effective.

@:Derek – Faith comes first, and my understanding of repentance is by inference and intuition – not from explicit New Testament teaching (Old Testament is irrelevant IMO, since there was no salvation available).

I am addressing the fact that many/ most self-identified Christians, and in increasing numbers – are working 8 plus hours a day, five days a week in service to the strategically and purposively evil globalist totalitarian bureaucracy – in one of its protean manifestations.

This situation is not going to stop, and there are essentially no “good” niches in The West within which Christians can earn a living – – so what is a real Christian supposed to do?

That’s what I am addressing. How does repentance work (how is desired salvation attained) when someone has zero intention of ceasing from regular sinning?

The fact that we have a problem is something that became very evident in 2020 among my doctor friends.

Their enthusiastic participation in the agenda of evil, their failure to notice and inwardly reject calculated untruthfulness on a colossal scale, and their dishonest denial of evil intent – brought them to act upon an implicit assumption that the globalist totalitarian establishment are the legitimate moral arbiters of this world.

What is urgently needed is a conceptualization of how to stay Christian, become more strongly Christian – despite daily/ hourly (in intended future) participation in strategic evil of an extreme kind.

Trad Christianity does not provide this, because it assumes either that faith is everything and behaviour is irrelevant (when in fact behaviour is often corrupting of faith); or else that people ought to stop sinning – i.e ought immediately to find a way of living in which they are not complicit in evil… which is impossible, and something that I’m sure Jesus never required of his followers.

I saw this meme and thought, with bemused irony, about your comment here (and your post) immediately.

Ha! That meme tells me a lot about its author! And not good!

But of course there is Jesus’s Example to consider. ( But also different Gospels differ on this, there is inconsistency on this.) In broad terms, Jesus spent the three years of his ministry with a bunch of sinners ( ie human beings, but also some types who were particularly offensive to the mainstream priests) and didn’t seem to spend much of his time demanding that they ceased from sinning or else.

I suppose all protestants would have to admit that we all sin and cannot stop, and salvation is by grace and faith, and while Im sure this is not the whole story, it is a basic and vital truth.

So if Jesus was compelled to answer yes or no, he would indeed have said follow me, and feel free to continue leading a sinful life – because that is exactly what everybody who has ever lived (except Jesus) always has done and will continue to do.

But don’t pretend you aren’t a sinner – don’t presume that you are already fit for Heaven and wholly aligned with God’s will this side of resurrection.

That’s the big no no.

I’d say! He only directly commanded it twice (John 5:32; John 8:11), and he called for general repentance three times (Matthew 9:13/Mark 2:17/Luke 5:32; Matthew 4:17; Luke 13:3-5). Notably, the triple reference is quoted inconsistently: only Luke 5:32 mentions repentance!

It’s so rare that you have to ask what Jesus really meant by the term.

I don’t agree that they are inconsistent. I know you discount the Old Testament, but the difference between the Old and New is quite insightful on this point.

The Hebrew word for repentance is deed-based turning away. It most like English Definition #1. But the two Greek words for repentance are more like the English Definition #2.

The most shocking part of my examination of this topic is that there is almost no overlap between the Old and New Testaments. They simply do not use the same language. The Old Testament—including the Greek Septuagint—concept of repentance is almost completely absent from the New Testament.

Jesus taught a renewal of the mind, or, as Jesus said, the heart. This was in line with Definition #2. He rarely pushed for Definition #1, neither in his words or deeds. The exception appears to be John 5:14 and the spurious John 8:11, but even those are of the type “stop doing this specific thing.”

When I read the Gospels on repentance, I see John the Baptist (implicitly!) teaching old-school repentance (#1) while promising that it would soon be replaced with belief (#2). Per here, if you ever read the Synoptic gospels and Acts together, look for this theme specifically and it will stand out. I think you’ll find strong coherence with the fourth gospel.

Well, in the OT and for John the Baptist; all Men who died went to Sheol – so their religion was all about what happened during mortal life (which was why their Messiah was conceptualized as an earthly saviour – an ideal King).

So repentance had to be about amending behaviour, ceasing from particular (listed) sins, during this mortal life – because there was nothing else for repentance to be.

Not least from my theoretical Mormon background; I don’t regard the Bible as either complete, or solely definitive; so the lack of clear Bible teaching on the nature and demands of repentance is not fatal to me.

There is enough clarity and repetition wrt Jesus’s teaching and the statements of the author in and of the Fourth Gospel to do this – I think.

I see repentance as a concept we must derive by implication from the core assumptions of (for instance) the nature of God the creator, what Jesus did and offers us, what it is to be a follower of Jesus Christ.

One aspect is that in this mortal life we can only make a temporary commitment of any kind. This is so obvious a fact of things, that it must be taken into account by the scheme of salvation.

We need to realize that God will make it possible for everybody able to desire Heaven to be able to do what is necessary to attain salvation. This includes stupid people, weak and easily influenced people, people living in terrible circumstances, people who have experienced only non-Christian and anti-Christian religions etc.

To me, this all points to repentance (in the third sense, more or less) as part of the needful.

…

One aspect is that in this mortal life we can only make a temporary commitment of any kind. This is so obvious a fact of things, that it must be taken into account by the scheme of salvation.

When I was younger I spent more time studying the Old Testament than the New Testament. I bring this up because calling repentance a “temporary commitment” corresponds to the Old Testament concept of repentance and atonement. Man’s repentance and God’s atonement were temporary. Sin could only be covered over temporarily. It was obviously true to the Hebrews—or, according to Jesus, it should have been—that no man could receive permanent forgiveness under the law. This is what we find in the books of Romans and Hebrews with respect to the Old Covenant.

Under the New Covenant, sins are taken care of by Jesus. There is no need or role for atonement. There is not, strictly speaking, even a need—requirement—for repentance (from the limited perspective of salvation, that is). Forgiveness is permanent and (mostly) unconditional.

I think what you are describing is your recognition that the Old Covenant cannot work due it is temporary nature. There is simply no way for a person to become truly pure in this mortal life. They must first die in order to be pure. And that is the purpose of the New Covenant: to ensure that upon death new life takes place.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but you seem to be arguing that this logically demands that God will make it possible for everybody to desire heaven and be able to do what is necessary, even without being an explicit follower of Christ. Without espousing universalism, I’m not sure how this could work. I’m not suggesting it is wrong, but I have no insight into it.

When people said “we need a revival”

Well, sure I would agree…but what we are going to do with one if it indeed came?

Also the reason why a real “send the fire” type of Revival has not happened is frankly, the bride is filthy.

Now, our RP friends will blame women, Biden, liberal churches, churches not putting the letter “A” or “F” on women who had sex out of wedlock (adulterer / fornicator).

The reason why I’ll never attend a church again or join one is for the fact that I really dont want to be around gossiping hypocrites. Theire sins are “forgiven” and yours……well, you need to suffer the consequences of said sins. God knows their heart, but your heart just isnt as mature and loving as theirs……..

We are told to not “forsake the gathering”

Jesus never said that. Jesus said “when two or more are gathered in my name I AM there”

Jesus knew even then many would not be welcome in the House that men built because of sin. He gave warnings to the Pharisees, but who are the Pharisees of today? The whitewashed tombs leading most of worldwide Protestantism today if truth be told.

Sin is sin……well, except RP christian men evidently, they dont sin. God knows their heart!

What Bruce is saying above is similar to what you are saying.

The scarlet letter “A” (or “F”) is supposed to prove repentance. Consider Gunner Q’s comment from six years ago:

It’s not enough to have a change of the heart, you have to prove it outwardly. Whatever happens inwardly is just never enough for the RP.

But, as you note, there is very little inward revival happening, and even if we had inward revival, it wouldn’t be enough to satisfy what people want: full outward revival.

General question.

Do you agree with the trad-orthodox idea that that – because all Men must await the Second Coming and Judgment before they can attain resurrection to eternal life – when we die our spirits go into a kind of coma to await these events?

I find this idea so utterly bizarre, and at variance with everything Jesus (seemingly) implies during his teachings, that I could scarcely believe it when I heard it preached to me.

But I suppose that if one takes seriously the Second Coming, as most Christians apparently do, then there must be something important for Jesus to do – and this fits the bill.

This strikes me as one of those doctrines (like the separate creation of angels) held by priests and theologians, but absent among the simple masses who have made up the vast majority of Christians through history.

I mean that the simple masses (among whom I include myself) have always expected (and believe they have been promised) that resurrection and Heaven follow almost immediately after death.

(And they/I also believe that humans can become angels, and probably vice versa.)

Yes. Despite your various writings on the subject, I don’t truly understand your objection to this. I genuinely don’t see the problem.

Why? What did Jesus teach that might be at odds with this? Aside from the 66 references to Sheol in the Old Testament and the lack of ambiguity in Paul’s New Testament letters about what happens to dead people (including the “great cloud of witnesses”), I’ve also thoroughly examined all 29 references to “hell” in the NT and found deathless sleep to be the only possible explanation.

If your objection has to do with the philosophical theories of time, I’ve discussed that as well.

I can’t answer why I find it bizarre! If you don’t – then there is no more to be said.

Continued from above – wrt to your quote:

The answer is that the final commitment to choose salvation happens after death. At which time everyone is confronted by the possibility of salvation , and can choose it – regardless of mortal experience.

The importance of repentance is that resurrection requires that we be re-made wholly-good. This means we must give up everything that is not aligned with loving creation – (negatively put) we must agree to all our sinful nature being eliminated.

This is the repentance that enables salvation.

During mortal life, the main need for repentance is that repentance is the recognition of good and evil – the acknowledgement that evil is evil; and the commitment to the side of good.

Knowing and endorsing good, knowing and repudiating sin, are instances of learning, of spiritual growth – this is part of what we are supposed to be doing with our lives, why we are sustained alive, how we become better.

I think that some people are kept alive a very long time because God recognizes that they have some sin that (post-mortally) they will refuse to recognize as a sin – that they will refuse to repent.

For instance, resentment seems common nowadays, and is actively encouraged officially and in several races and nations. i.e. People nurse lifelong resentments against something that happened to them, or some person or group – strong even many decades after the event, or after the offender has died – and they will not let go of this resentment, will not acknowledge it is an evil attitude – but will repeatedly try to justify its continuance (and convert others to the same resentment).

(I think) God hopes that by keeping people alive longer, giving them more experiences, enabling the opportunity to experience the adverse consequences of their own (and other people’s) resentment – this will be repented – after which that person can die with a good expectation he will then agree to salvation.

Pingback: On Error and Sin - Derek L. Ramsey