Note: This is part of a series on the Trinity from a rational, non-mystical perspective. See the index here.

As most readers already know, I wrote a series on the Eucharist where I claimed that the Roman Catholic Eucharist was completely absent from the first three centuries of the church. I made this claim because I also assert that Roman Catholicism arose in the late 4th century.

If Roman Catholicism arose late in the 4th century, then all of its core doctrines must be checked to ensure that they are not historical anachronisms. While most are fairly straightforward, one fundamental question remains: was the doctrine of the Trinity also an invention of later years?

There is no historical doubt that the early church debated the doctrine of the Trinity in the 4th century (amidst Arianism) and later. In those centuries, the role of Jesus was first defined specifically while the role of the Holy Spirit would be explained later. But were these explanations merely refining and clarifying what was already explained in scripture (like, supposedly, the other Roman Catholic doctrines, as described in “The Trinity and the Protestants“) or was it a doctrinal innovation or invention?

The question is surprisingly difficult and complex.

For many years I’ve been working on an historical analysis of the Trinitarian doctrine by various early writers up through the 4th century (as I did with the Eucharist). Alas, it remains incomplete. So, instead, today I’ll be starting a lengthy multi-part series on what various writers have said about the Trinity and analyze their views against the canonical statements by major denominations.

Let’s start by examining and discussing the views of James Attebury in his recent article which represents a relatively traditional view.

As I proceed, keep the following references in mind:

Exhibit A: “Grammatical analysis of John 1:1c and John 1:14“

Exhibit B: “When Did the Word Become Flesh in John 1:14?“

These are the backdrop for my analysis.

To be clear, I’m not going to refute Trinitarianism, nor prove the “Oneness of God” Christology, nor prove Adoptionism, Partialism or Modalism, nor prove Arianism or Sebellianism, nor prove or disprove any other Christological belief. I’m only going to show that Attebury’s reasoning is deeply flawed and that his argument in favor of Trinitiarianism does not logically follow from his claims. This is what I mean by “difficult and complex.”

As I pointed out in Exhibit A, the traditional viewpoint is that the Trinity is a mystical, axiomatic truth to be accepted by blind faith, not a truth that is proved or even provable. This has been the nearly universal explanation by the church over many centuries. Attempts to prove it rationally have generally been unsatisfactory.

But first, a warning. As most Protestants and Catholics hold that the doctrine of the Trinity is equal in importance to the resurrection, a matter of one’s salvation, I suggest that anyone who cannot handle scholarly critical examinations of such beliefs sit this one out. But, feel free to disagree with me in the comments.

Introduction

Let’s begin.

Bernard’s interpretation of the Word of John 1:1 is almost identical to that of adoptionists who deny the pre-existence of Jesus Christ as well.

It is interesting that different Christological views can be derived from a single interpretation. This suggests that the passage is complex (and possibly unclear) and should be handled with care. But, more importantly, in Exhibit A’s argument, I noted something similar: the argument is hostile towards incarnational theologies, but it doesn’t rule out many of the alternative non-incarnational Christologies.

There is something about incarnational Trinitarianism that lives and dies on a tightly specific, inflexible, interpretation of scripture. If you pay close attention, you’ll notice that Attebury assumes one (and only one) possible explanation. He allows himself no wiggle room for personal or corporate error, nor any room for personal discernment. If any of one of his assumptions turns out to be false, the whole thing falls apart. There is no room for flexibility. As we will see below, for someone who seems to stress reason and argument, his viewpoint is heavily dogmatic.

Many of his assumptions are deeply flawed.

If Attebury were not responding to a specific Christology which holds these beliefs, his objection would beg-the-question (i.e. be circular reasoning). Attebury here presumes that the reason for belief is that a prior decision about what the passage must mean (“eisegesis”) rather than what the passage actually says (“exegesis”). As we’ll see below, this also appears to be projection, for Attebury’s reasoning involves much eisegesis.

Now, let’s talk about why his point is wrong. The basic definition and grammatical of the Greek “word” is not personal (e.g. it’s not a pronoun). Moreover, John 1:1 says nothing about the Son, just as Genesis 1 (“…and God said…”) says nothing about the Son when speaking of God speaking. Even if “Word” were personified—as in God’s Wisdom—such ‘personhood’ would merely be a figure-of-speech.

The point is, we are obligated by default that the “logos” (i.e. word) was literally impersonal unless it was made clear that John was speaking about neither literal words, nor any of the fourteen different standard meanings of ‘logos’,[1] nor merely an inanimate personification figure-of-speech. To do otherwise risks begging-the-question.

See also: Kermit Zarley, “Is ‘The Word’ in John 1:1-3 an ‘It’ or a ‘Him’?”

The Prologue to John’s Gospel

John 1:1

1. The Word is identified as God.

John tells us that “the Word was God.” If the Word was God, then the Word is personal because God is personal. As Michael Burgos puts it,

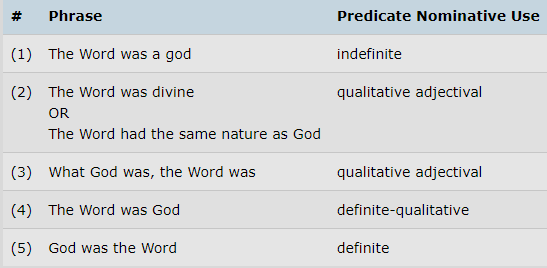

I don’t think that Attebury realizes the significance of the admission that Michael Burgos is making here. It is a massive concession to the non-Trinitarian argument. Here is the chart from Exhibit A:

Count how many translations in this list use each option. The vast majority use (4) and none use (3). To find a translation that uses (3) you have to go to the New English Bible, the Revised English Version, or the grammarian Daniel Wallace (someone that Attebury has cited on a number of occasions). To find a translation that uses (2) you have to go the Moffatt Bible.

Now notice that Burgos’ description…

…is almost identical to…

This is very strange indeed! We also pause to briefly note that Burgos’ version is much less literal than the original Greek, more of a paraphrase: he changes the tense[2] and adds the word “all.” This is strange for Attebury to cite approvingly, but we’ll discuss that more in a bit.

Traditional Trinitarians will almost universally select the fourth option from this list, not the third (unless, notably, they don’t want to use this verse as a Trinitarian proof-text). Selecting the third option actually reflects the modern scholarship on the issue (e.g. Daniel B. Wallace argues for it). In Exhibit A, I argued that the third option stands conclusively against Trinitarianism.

Pause and consider that for a moment. Burgos’ translation reflects an acceptance of the conclusion of modern scholarship. In doing so, it implicitly rejects most of the Trinitarian arguments that have been made over the centuries (which generally rely on the fourth or fifth option being the correct one).

A “qualitative adjectival” understanding doesn’t work the way that Burgos or Attebury are using it. To make a logical conclusion like…

…you’d have to choose the fourth option (“definite-qualitative”) or even the fifth option (definite). This level of definitiveness and deduction…

…is why traditional Trinitarians almost always choose the fourth or fifth option in the first place. It’s simply not possible to take a word with a qualitative adjectival force and wrench it so hard as to make such definitive claims.

Burgos’ qualitative adjectival translation is not really compatible with Burgos’ and Attebury’s definite conclusions.

You may find this confusing, so let’s briefly take the time to understand this. I’ll use two examples to illustrate the differences between a qualitative and definite explanation.

(1) What God was, the Word was

(2) God was great

(3) Therefore, the Word was great

(4) The Word became flesh in Jesus

(5) Therefore, in Jesus was greatness.

See how this silly, but clear, example conveys a quality rather than an identity? The problem is that you can never derive Trinitarianism from a purely qualitative approach. Compare this to the purely definite approach:

(1) God=Word

(2) Word=Jesus

(3) Therefore, Jesus=God

It is easy to understand how this works, how each equality conveys identity. And had Attebury and Burgos used a translation that promoted this view, we’d be having a different discussion (or all become Modalists). But they didn’t.

Now, look closely at the second option in the chart: “The word was divine” and “The word had the same nature as God.” These are qualitative explanations that function in a way similar to adjectives (thus “qualitative adjectival”). Attebury rejects these because this would have divinity or the nature of God—rather than God himself—”becoming” flesh. This is not Trinitarian. Now when you look at the third option—”What God was, the Word was”—it is equally qualitative, only it refrains from explicitly stating what those qualities are (i.e. it avoids translating the text in a way that presumes an interpretation).

Is it divinity, the nature of God, or (as in my silly example) greatness? The third option in the chart differs from the second option only in that it refrains from stating what the quality is explicitly, because John didn’t state it explicitly. But it is still qualitative, not definite. “God” describes the “Word” like an adjective: the Word is godlike, as it were.

So consider Attebury’s argument “if God is personal, the Word is personal” in terms of a qualitative, adjectival sense. If this were true, then in John 1:14, it would be the nature of personhood—the quality conveyed by “word”—that became flesh in Jesus Christ.

You can now see how Attebury’s argument falls to pieces. He’s using an argument based on a qualitative translation, but he’s not using a qualitative interpretation. He’s using a traditional definite interpretation. This is self-contradictory.

Similarly, Burgos’ use of “All” here is presumptive and contradicted by his choice of interpretation. Burgos’ use of “all” would be most appropriate if he had selected the fifth option from the chart: the purely definite. After all, we have no other indication from the text that John was referring to “All” that God was. Indeed, Burgos himself does not believe that “All” includes God Jesus being the Father! If Burgos truly mean that all—literally everything—that God was became flesh in Jesus, then Jesus must have been the Father in the flesh. So “all” doesn’t actually mean absolutely everything here.

Burgos has researched the Trinity and its scholarship well, so he knows that the scholarship on the fourth and fifth options (the “definite”) has essentially ruled them out. So he is trying to save his Trinitarian view by adopting the third option (the “qualitative”), but trying to retain the sense of the fourth or fifth (the “definite”). This is just not a intellectually or logically valid approach. Remember when I said “Burgos’ version is much less literal than the original Greek?” He’s been forced into a corner.

Since Attebury basis his entire response on this one basis, we could simply stop here and rule out his entire post as a logically invalid argument. But there are more errors.

John 1:14

5. The Word is identified as Jesus in John 1:14 who became flesh for us:

John claims to have seen the glory of this Word who became flesh. But ideas and plans do not become flesh or become incarnate, only a person could become incarnate.

I wrote about this at length in both Exhibit A and Exhibit B. Suffice it to say, I’m not impressed by this argument (which, incidentally, is still very much taking these verses in the definite, non-qualitative sense).

The Word is not identified as Jesus. As shown above, the explanation is somewhat technical, but here is a summary:

John 1:14 combines ‘the Word’ and the mass noun ‘flesh’ with the semi-copulative ‘became’. The word ‘flesh‘ has a qualitative force.

As with John 1:1, Attebury is taking a word with a qualitative force and interpreting it as if it had a definitive force. He’s interpreting John 1:14 as if it were conveying something other than a quality.

To further illustrate the absurdity of Attebury’s approach, we need only look at the previous two verses:

Right before talking about the word becoming flesh in the birth of Jesus, John talks about people becoming the children of God by birth. The Trinitarian has no problem interpreting the birth of the children of God qualitatively, so why the resistance to the word becoming flesh (in Jesus) qualitatively?

So both the grammar and the context demand an interpretation other than the one Attebury has supplied.

But that’s not everything.

Yes, v14 is sandwiched between Jesus as an adult, the children of God receiving Jesus (being “born”) as believing adults, and Jesus being baptized as an adult. The context of the passage suggests that the word became flesh when Jesus was baptized as an adult, not when he was born. In fact, were it not for external traditional, there would be little reason to logically conclude that the verse had anything to do with Jesus’ birth.

John’s Gospel never mentions Jesus being born. There are no mentions of genealogies, Mary and Joseph, shepherds, wise men, flights to Egypt, ruling monarchs, tax registrations, or even Jesus’ early years. Rather, John’s written narrative of Jesus’ earthly life begins with Jesus’ baptism.

The view that John 1:14 is about Jesus’ birth (and thus incarnation) is a matter of external attestation. In other words, it is the conclusion from external evidence and argument. It is plainly circular reasoning to take that conclusion—that John 1 refers to Jesus’ incarnation—and use it to prove that same conclusion: Jesus’ incarnation. But, that is precisely what Attebury and Burgos are doing here when they use the external tradition of John 1 (the premise containing the conclusion) to show that the John 1 proves the incarnation is true (the conclusion).

Jesus as the Word

But why does John choose to describe Jesus as the Word? The obvious answer to that question is because that is who he is.

No, that is not the obvious answer at all. In fact, it’s obviously wrong.

John never describes Jesus as the Word in a definitive, non-qualitative, non-adjectival sense. At most it says that the word is made flesh in the person of Jesus. These are not the same thing at all! Attebury himself implicitly attests to this through his specific citation of Michael Burgos and his subsequent rejection of Modalism (see below).

As I pointed out in Exhibit A, a purely definite force leads to a reversible (or convertible) proposition where “The Word was God” is equivalent to its converse “God was the Word.” This type of proposition (where A→B and B→A are both true) is known as a definition. This leads to Modalism or Sabellianism. So Trinitarians, including Attebury, reject this (and thus reject the purely definite force).

If you want to say “The Word was Jesus” (which is what v14 says, kind of) and “Jesus was the Word” (which v14 does not say) you must similarly have a definite convertible proposition. And yet, despite rejecting the purely definite force, he still argues for a conclusion based on a definite force: “Jesus as the Word.” Does that sound familiar? It should:

(1) God=Word

(2) Word=Jesus

(3) Therefore, Jesus=God

The purely definite force is in full display in “Jesus as the Word.” Without this, it is merely “Affirming the Consequent,” a logical fallacy.

When John describes Jesus “as” the Word, he is doing so in a fully qualitative sense. The phrases “the word was God” and “the word became flesh” are not definitions. They must be interpreted as conveying qualities in some sense, not identity (especially in an absolute sense).

Attebury’s handling of the languages is quite sloppy. He may cite a source which argues for the qualitative sense, but then he uses it in a definite sense in his argument, as if it were a definition or close to it. He’s simply not precise enough with his language to make a logically consistent theology.

As I wrote in Exhibit A, the words that John uses in John 1:1c and John 1:14 are both used in a qualitative sense. One cannot say that Jesus is the word without taking the first step and twice qualifying what is meant by that. It is simply not true as a general definition that Jesus is the Word.

John 1:3,10

4. The Word who created all things in John 1:3 is identified as Jesus in John 1:10:

John 1:3: “All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made.”

John 1:10: “He was in the world, and the world was made through him, yet the world did not know him.”

Since John 1:10 tells us that the very same person who walked among us and was rejected by the world was the same one “through” whom God the Father created the world, that must mean that the Word of John 1:1-3 is Jesus himself. And since Jesus is personal, the Word is personal.

The pronouns used in the passage can mean either “he” or “it.” For example, here is one alternative interpretation of John 1:3:

The explicit subject of John 1:1-5 is “the word.” Translating it with the pronoun “it” instead of “he” avoids begging-the-question. Translating it as “he” is possible, but presumptive. By contrast, the subjects of John 1:6-13 are John the Baptist and Jesus, not “the word,” and so the pronoun “he” is appropriate there. Different subjects, different pronouns.

Attebury uses his own external choice of translation to allow him to use the same pronouns in an argument that makes the word out to be Jesus. This is rather obviously both an equivocation fallacy and circular reasoning (i.e. using a translation to prove what the original must be).

No, it’s just not a very strong argument. Let’s try an unbiased atheist test. Find an atheist and let me read and explain the translation (that doesn’t make the doctrinal presumption)…

1 In the beginning was the word, and the word was with God, and what God was the word was. 2 This word was in the beginning with God. 3 Everything came to be through it, and apart from it nothing came to be that has come to be. 4 In it was life, and that life was the light of humankind. 5 And the light shines in the darkness, but the darkness did not overcome it.

6 There came a man sent from God, whose name was John. 7 This man came as a witness to testify about the light, so that through him all would believe. 8 That man was not the light, but he came to testify about the light.

9 The True Light, who gives light to every person, was coming into the world. 10 He was in the world, and the world came to be through him, and yet the world did not know him. 11 He came to his own and his own did not receive him. 12 But to as many as received him—to those who believe in his name—he gave the right to become children of God, 13 who were not born by blood, nor by the will of the flesh, nor by the will of a man, but by God.

…and we’d be forced to conclude that no reader would need to equate the word and it with the he in the later verses. I don’t have an atheist I want to bother with this, so I performed the atheist test on Grok AI instead. Here is what I found:

The translation of John 1:1-13 you’ve provided does not explicitly rule out Modalism or Adoptionism on its own, but it does contain elements that are traditionally interpreted in ways that challenge these theological positions.

Without leading the witness or otherwise prompting it, it agreed with me that John 1 only rules out Modalism and Adoptionism by incorporating external attestation. In its full response, it mentioned “broader scriptural context” and “theological tradition,” both external attestations. The best it could do was mention that there are nuances of interpretation, but we’ve already acknowledged this (e.g. ambiguity in pronouns). But Attebury uses John 1 as direct, explicit, and conclusive (internal) attestation of the incarnation.

What we have here is Attebury using translations as proof. But since translations are derived from the conclusion of the Trinitarian argument, using those translations (the conclusion) to prove the Trinity (the conclusion) is obviously—obviously—circular reasoning.

Attebury thinks he’s made a strong point, but only because he has failed to recognize the errors in his reasoning. There isn’t anything in John 1 for “modalists and adoptionists” to “overlook.”

Anyway, feel free to try out this test on an actual atheist.

3. The Word is described as being in personal relationship with God.

John tells us that “the Word was with God.” The preposition “with” implies a relationship between the Word and God. According to John 1:18 the Son was “at the Father’s side.” But if John had wanted to teach that the Word of John 1:1 was impersonal and not a distinct person from the Father, he could have said that the Word was “in God” rather than “with God.”

There is a logical flaw in this argument: a false dichotomy.

Attebury is contrasting two different positions: his own and that the Word was impersonal. But these are not the only options. As I noted above, personification is a figure-of-speech. It is an extremely common figure-of-speech in Hebrew and Ancient Near East thought, where essentially everything that exists is viewed as being “alive” in some real or figurative sense.

It is as Bruce Charlton asserts, that existence itself is essentially personal. Personal relationships reflect that fundamental realities of existence and truth.

Ed Hurst has also discussed this at length and I agree with him.

John wasn’t trying to teach that logos was impersonal. He had no need to teach that. It never would have occurred to him to teach that. Nor was he trying to teach that logos was a distinct person apart from the Father, as he had no concept of the Father being a distinct person from the Son. Such Trinitarian language is not found in John 1:1.

As I’ve pointed out before, unless one was already familiar with Trinitarianism, no one would come to the conclusion that Attebury has come to. Go ahead, find an atheist who is unfamiliar with the Trinity and ask them to read and explain John 1:1 in simple language. They won’t describe a Trinity, nor will they talk about distinct persons. It simply isn’t there.

If you don’t have an atheist, here is what Grok AI said. There is no mention of persons or divisions of God, but a clear indication that it is symbolic or a figure-of-speech.

The distinction between being “with God” and, say, being “in God” is not as meaningful as Attebury suggests. Consider how many different prepositions are used regarding Christ and the members of his body: of, in, with, through, and for. These prepositions are not rigidly distinct in their meanings. As in English, there is significant overlap between choices of prepositions.

Revelation 19:13

2. Jesus Christ is called the Word of God in Revelation 19:13:

Jesus is a person. And because he is personal, the Word of God is personal. Revelation 19:13 is telling us that he is the Word of John 1:1 and he has not ceased to be the Word of God. If Jesus is personal, then the Word is personal.

There are multiple ways to respond to this, any one of which refutes Attebury’s claim.

First, the name of a person does not embue that name—which is not a person—with personhood because it is attached to a person. The Word is not a person because Jesus had the name “the Word of God.”

Second, Jesus was given many names by which he was not identified: Mighty God, Extraordinary Advisor, Everlasting Father, and Ruler of Peace. No Trinitarian—which treats the Father and Son as separate persons—thinks that Jesus is actually the Everlasting Father. Obviously the purpose of these names is to identify Jesus with the God. The names of Jesus rather obviously describe God, not Jesus himself. The fact that Anti-Trinitarians use the exact same argument that Attebury is using (with “Everlasting Father” instead of “the Word of God”) to refute Trinitarianism makes this argument a stalemate, a dead end.

Third, the name of something is a Hebrew idiom for the the power or authority of something. It’s a description of agency, not identity. If a person says “in the name of God, I drive out this demon” they are making a claim to another’s authority as their agent, not claiming to be God. Revelation 19:13 is assigning to Jesus the authority of the Word of God. When Jesus speaks, he speaks on behalf of God, as if it were God himself speaking. That is full agency and authority, not identity.

Fourth, this is the “anachronistic fallacy.” Revelation 19:13 takes place after the resurrection, after Jesus has ascended to the right hand of God. To be “at the right hand” is another Hebrew idiom that refers to the delegation of power and authority. This sense is captured in the English “right hand man.” John 1:1 refers to events that occurred prior to the ascension, and so can’t be applied directly as Jesus had not yet fully taken the name (or power) of God until he sat down in power. Or, put another way, it begs-the-question to say that the descriptions of Jesus and his power and authority after the ascension are equivalent to Jesus at his birth.

If Jesus already had all his power, authority, and identity when he sat down at the right hand of the Father in heaven, then Attebury’s argument—which presumes that Jesus never possessed less than his full divinity—takes away all the significance of the ascension.

Lastly, Attebury’s use of Revelation 19:13 is somewhat novel and rare. I can’t say that I have seen anyone ever make this argument before. Even ignoring the four reasons that doing so is logically unsound, this would nonetheless makes me inherently suspicious of its validity. None of the Anti-Trinitarians that I have read have identified this as a Trinitarian proof-text.

Philippians 2:6-7

As the parallel passage in Philippians 2:6-7 tells us, the one who was in the form of God took upon himself our human form:

First, it makes no sense to speak of the image (or form) of God as God himself. Man was made in the image of God, but was not God himself. God is not his own image. Images, forms, and likenesses are not literally the thing they represent: the symbol is not the thing symbolized. In Hebrew, the root of the Hebrew word for ‘image’ means “shadow” (see Psalm 39:6). The clear implication is that Adam—man—was in the form of God, and Jesus was born in the form of Adam.

Second, I’ve bolded the word “was” in the verse quotation, because it is not found in the original Greek. Here is an accurate translation using only the participle:

Grammatically, the tense of participles need not correspond to the tense of the main verb to which it relates. The use of the simple past tense “was” presumes a specific theology. It leads one to conclude that Jesus was of a certain mindset at one time, but he changed his mind and had a different mindset at some later time. But when the word used is “being,” the implication of this sense disappears. This highlights, again, how taking the translation (the conclusion) to show Trinitarianism (the conclusion) is circular reasoning.

Third, the meaning of this passage among Trinitarians is not universal. Here is Attebury’s explanation:

But to say that Jesus “emptied himself” is not to say that he emptied himself of something he had, but that he himself is the one who is emptied. The verb “emptied” communicates the idea of being humbled or making oneself nothing. That is why the ESV correctly translates the verb as “made himself nothing.” It is a description of the humiliation of Christ through taking upon himself human nature. It is humiliation through addition, not subtraction.

Attebury understands that “emptied himself” means “becoming human” in addition to his divinity. But this creates a logical contradiction. If Jesus retained his full divinity, then he must have been the ontological equal of God, regardless of his humanity. If Jesus’ human form was created in the image of God and was without sin, and he retained his full divinity when he became a man, then it could not have been a humiliation. This is not, in any way, “nothing.”

The problem is that there is no logically consistent way to balance the “dual nature of Christ.” Theologians can identify places when Jesus acted out of his divine nature (e.g. miracles) and when he acted out of his human nature (e.g. in the Garden). But there is no systematic way to explain how to balance these together. It is why most theologians throughout history have called it an incomprehensible mystery. As we’ll see when we discuss James White, attempts by theologians to define it logically always fail.

The problems, which Attebury completely avoids in “What is Kenotic Theology,” are the following:

First, it seemed to turn Christ into an unexplainable aberration: fully God and fully man at the same time.

Second, if Jesus were both omniscient God and limited man, then he had two centers, and thus was fundamentally not one of us.

Kenotic Theology was developed to address the flaws in traditional Trinitarian theology. While Attebury contends, correctly, that Kenotic Theology is incorrect, he simply falls back on his own Trinitarian views without considering the problems that Kenotic Theology is trying to solve in the first place. Since Attebury could have rejected both views, this is unhelpful because it begs-the-question on Trinitarianism.

Third, when this passage is viewed as a chiastic structure, it’s meaning changes:

A: who in the form of God being

B: he did not regard a plunder to be equal to God

C: rather, he emptied himself taking the form of a servant

C: and being found in the configuration of a human

B: he humbled himself becoming obedient until death, even death on a cross

A: wherefore, God highly exalted him

When viewed this way, we find three conclusions:

(A) Jesus was in the form of God after God exalted him at his ascension, after his death and resurrection.

(B) To be humbled and obedient unto death requires a lack of equality with God. Since God cannot die, Jesus could not claim equality with God because he had to die. A lack of divinity was required to die, so Jesus could not have been exalted (i.e. in the form of God; equal to God) when he was crucified.

(C) To be “emptied” simply refers to being a human and a servant (as opposed to being God).

Brother Kel writes:

And further yet, the Trinitarian assumes the words “and being found as a human” somehow imply that Jesus found himself to be a human having added a human body to himself. One only has to meditate upon this notion momentarily to realize its absurdity. Why would Paul say such a thing about someone who had intentionally become a human being? Is it not clear that Paul’s point is that finding himself to be a human being rather than a divine being, Jesus humbled himself? And this expression only further describes what Paul had just said – that Jesus came into his existence in the likeness of humans.

Paul seems to be saying that because Jesus was in the form of a human and not of God, he humbled himself by his death on the cross. Then, having died, he was exalted into the form of God by God himself. This is basic Christianity, but it’s not Trinitarianism.

1 John 1:1-2

6. John tells us that the Word was heard, seen, and touched by him in 1 John 1:1-2:

This Word of life is Jesus whom the Apostle John was with. But ideas and plans in God’s mind are not heard, seen, or touched. Persons are heard, seen, and touched. John did not touch an idea or a plan, but he did touch the Son of God who is a person.

First, plans can, in fact, be seen, heard, and touched. In English we have an idiom that conveys precisely this point: “The plan has come to fruition.”

Second, John says that the [word of] life was testified and proclaimed (i.e. “spoken” and “heard”). These are actual words. Let’s increase the context by including the next two verses:

What was declared—the actual words—have been “seen” and “heard” and “written.” Yes, when you hear the word of God spoken, you are “seeing” and “touching” it.

Third, a simple reading shows that John neither literally nor figuratively ever says that Jesus is the word. He mentions the word in the context of Christ one time (“concerning the word of life”) and later, arguably, by implication (“the [word of] life was made known” and “declaring to you the [word of] life in the age to come“) without ever identifying Jesus as the word. The word is something associated with Jesus. Jesus was concerned with the word of God, he made that word of God known, and he declared that word of God to be life eternal. He was not the Word of God.

The fact is, Attenbury sees in John something that rather plainly isn’t actually there. Read it for yourself. It’s not there! John failed to describe the Trinity in “1 John.” This strongly militates against the same interpretation for his Gospel, given the similarities between the first chapter of both.

Hebrews 1:1-2

7. The parallel passage in Hebrews 1:1-2 tells us that the Word is the Son:

Both the Word and the Son are described as being the one “through whom” God created the world.

Now hold up there, not so fast!

Scripture says that in many times and in many ways in the past, God did not speak through his Son. Trinitarians teach that Jesus was there at the creation of the world (as described in Genesis), that he literally spoke it into being. But the writer of Hebrews notes that the Son did not speak to us at any point in the Old Testament. This flatly contradicts many different Trinitarian claims that the Son is being spoken about in various Old Testament passages, not just the Genesis account.

Hebrews states that Jesus was appointed as heir of all things in these last days. If Jesus spoke the words of creation at the beginning of time, then this would be a nonsensical thing to say. Attebury has chosen a confusing self-contradictory translation. Here is a more literal translation:

So, no Hebrews does not say that Jesus created the world (it’s plural in the original anyway!), it says that he gave form to the ages. In Jesus, God gave form to all that he had promised. More to the point, it does not actually say which ages he gave form to, but given that it is “in these last days” it presumably refers to a kind of creation that occurred in the ages referred by “in these last days” such as the New Covenant of Christ (which Hebrews is primarily concerned with).

We don’t actually have to guess what it means, because there is a parallel passage that does this for us:

This makes it pretty clear that Jesus was the fulfillment of God’s purpose over the ages (or eras of life).

Attebury’s translation uses the word world. And it is true that the Greek word for ‘age’ can be translated world in English, but it can only be done in one sense only. And it isn’t the one you thought it was:

Indeed, the etymology of the English word world is this:

Middle English, from Old English woruld human existence, this world, age (akin to Old High German weralt age, world); akin to Old English wer man, eald old

Roughly speaking, it is a “old man age” or an era of time (e.g. an age of mankind). However, in the Greek it goes beyond merely a time period to encompass the realities or essence of life in an era, as in an “age of life.” In doing so, it captures the sense of eras as life transitioning from one kind to another over time. So we can speak of the age of prophets or the age of Noah, but we can also speak of an age of childhood or an age of evil, or even the spirit of the age because “age” does not pertain to specific time periods, but more so to the qualities of each era.

So corrupt is this verse in the Bible, that the NIV translated ages not as world but as universe! Consequently, given these ridiculously misleading translations, it is difficult for many Christians to understand that when the Bible speaks of the ages past…

He has made known to us the sacred secret of His will according to His good pleasure that He planned beforehand in connection with him, with a view toward the administration that occurs at the fullness of the times, to unite under one head all things in connection with Christ–the things in the heavens and the things on the earth in connection with him.

…that he worked in Christ when he raised him from among the dead and seated him at his right hand in the heavenly places, far above every ruler and authority and power and dominion and every name that is named, not only in this age but also in the one to come…

…and so that I could bring to light for everyone what is the administration of the sacred secret, which has been hidden for ages in God who created all things. He did this so that through the church the multifaceted wisdom of God would now be made known to the rulers and the authorities in the heavenly places. This was consistent with his purpose throughout the ages that he accomplished in Christ Jesus our Lord.

…it is not talking about the creation of the physical world (or universe), but of all the many worlds—spheres of life and action—that saw their fulfillment in Jesus.

The REV Bible Commentary explains the “making of the ages” in this way:

Paul speaks of the ages in the context of the mysteries—the sacred secrets—of God that were previously hidden but only now revealed in Christ. Prior to Christ, the ages were hidden. Only in Christ were they made, that is, given form.

God’s hidden purpose throughout all the prior ages was to bring salvation through Christ. And, ultimately, through Christ the ages were made, that is, revealed and brought to completion. And Christ—of the New Covenant—is also now the focus of the ages that are here now and to come.

Let’s expand the context by including two more verses that Attebury left out:

God, having spoken from old time to the fathers through the prophets in many parts and in many ways, has at the end of these days spoken to us by His Son, whom He appointed heir of all things, through whom also He has given form to the ages, who is the reflection of His glory, and the exact representation of His nature, and is upholding all things by his powerful word. After he had accomplished the cleansing for sins, he sat down at the right hand of the Majesty on high, having become as much better than the angels as the name he has inherited is more excellent than theirs.

It is the firstborn who inherits. When does scripture describe Jesus as being firstborn? Upon his resurrection. When does scripture describe Jesus as receiving his inheritance? After he had died, resurrected, and ascended into heaven to sit at the right hand of God the Father. It makes absolutely no sense that an always fully divine Jesus inherited anything from God and became greater than the angels. He already had all of that. Furthermore, it makes no sense that whatever he exaltation he received from God happened at his birth (as opposed to before or after).

It is just as we saw in Philippians 2:6-7.

Attebury’s claim…

…that God created all of creation (“the world”) through the Son is absurd and makes absolutely no sense in the context of Hebrews.

Summary

I would summarize our findings like this: infusing John 1:1 with a Trinitarian understanding forces it to say more than it actually says. Doing so leads to many different problems. The solution, then, is to not use John 1:1 as a Trinitarian proof-text, to derive it—if possible—from other clearer passages.

Footnotes

[1] The Revised English Version Bible Commentary gives the following non-exhaustive list of fourteen definitions for logos.

- Speaking

- Statement

- Question

- Preaching

- Command

- Proverb

- Message

- Assertion

- Subject Matter

- Divine Revelation (by God)

- Divine Revelation (by a messenger)

- A reckoning or account

- A financial accounting

- A reason or motive

[2] I did something similar with the semi-copula “became” in John 1:14, treating it as the full copula “is.” But I did not re-translate the passage. Rather, I provided a justification for why the passage should be understood in that sense.

How is the RCC & Orthodox and the vast majority of ”Redpillers”(as our friend LEXET once wrote at SF-who thirst for authority, Tradition and power) and who claim such is going to say the following is in line with past Church tradition, councils, and the Magisterium?:

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-01-11/gay-men-can-train-as-priests-says-italian-church/104807264

”The new guidelines still bar those with ‘deep-seated homosexual tendencies’ from being considered. (Reuters: Tony Gentile)

In short:

The new guidelines approved in Italy make clear that homosexuality in itself need not preclude a man from being ordained a priest.

All priests are required to maintain celibacy.

What’s next?

Some observers have welcomed the new guidelines, calling it a “big step forward”.

Link copied

Share article

Homosexual men can train to become Catholic priests in Italy but not if they “support the so-called gay culture”, according to new guidelines approved by the Vatican.

While stressing the need for celibacy, the Italian Bishops’ Conference guidelines — posted online on Thursday — open the door for gay men to attend seminaries, or divinity schools that train priests.

But they came with a caveat — that those who flaunt their homosexuality should be barred.

Pope apologises for using homophobic term

Photo shows A man wears a small white gourd shaped hat on his head with one hand up.A man wears a small white gourd shaped hat on his head with one hand up.

The pope used the term during a closed-door meeting.

A section of the 68-page guidelines was specifically directed at “persons with homosexual tendencies who approach seminaries, or who discover such a situation during their training”.

“The Church, while profoundly respecting the persons in question, cannot admit to the seminary and to Holy Orders those who practise homosexuality, present deeply rooted homosexual tendencies or support the so-called gay culture,” read the document.

However, the guidelines say that, when considering “homosexual tendencies” of would-be priests, the church should “grasp its significance in the global picture of the young person’s personality” in order to arrive at “an overall harmony.”

The goal of training priests is “the ability to accept as a gift, to freely choose and live chastity in celibacy”.

The new guidelines have been approved by the Vatican, the bishops’ conference said in a statement.

Pope Francis, 88, has throughout his papacy encouraged a more inclusive Roman Catholic Church, including for LGBTQ Catholics, even though official doctrine still states that same-sex acts are “intrinsically disordered”.

In 2013, just after taking office, Francis famously said that “if someone is gay and is searching for the Lord and has good will, then who am I to judge him?”

In June, however, the pope used a vulgar gay slur in a closed-door meeting with Italian bishops, according to two Italian newspapers, setting off a minor firestorm.

The pope had expressed his opposition to gay men entering seminaries, saying there was already too much “frociaggine” in the schools — using an offensive Roman term that translated as “faggotry”.

Some observers welcomed the new guidelines, with the head of New Ways Ministry, a US-based Catholic outreach for LGBTQ individuals, calling it a “big step forward”.

“It clarifies previous ambiguous statements about gay seminary candidates, which viewed them with suspicion. This ambiguity caused lots of fear and discrimination in the church,” said the ministry’s Francis DeBernardo.

Another advocate for LGBTQ Catholics, US Jesuit priest James Martin, told AFP it was the first time a Vatican-approved document included the notion that judging who was eligible to join a seminary “cannot simply come down to whether or not he is gay”.

Martin said he interpreted the new rule to mean that “if a gay man is able to lead a healthy, chaste and celibate life he may be considered.”

That of course will be ”mainstream”, traditional, and ”common sense” among Republicans, Democrats, Catholics, Orthodox, and Protestants in 20-25 years and you’ll be ”canceled” if you don’t agree.

Of course they do. I wrote about this in “Too Slow To React In Time.” This is exactly how gay politics took over most of the American denominations: slowly and steadily, without a single identifiable point in which the line was crossed, but crossed it was.

With this destigmatization, the Overton Window continues to shift.

A bunch of Orthodox Priests in Texas signed a letter to the Governor or some authority a year or two ago “demanding that a woman’s right to her body / her choice” was indeed in line with teachings of the church.

Mind you, most Orthodox priests in the USA today are former protestants, former hippies, former tune-on / tune in and drop out types……doesnt really surprise me.

Gay marriage and the like will be in both these churches very soon. In ten years, the Catholic and Orthodox churches will look like the the Church of England.

Tradition, ritual and nothing about Jesus. This has already happened in most (if not all) mainline protestant denoms. I overheard a Presbyterian minister talking a year or two ago at a Starbucks. he was telling a teen “Our mission is education, its the most important thing in the world, that’s who we are, that what the Presbyterian church is all about”

Some other denoms would say inclusion, being “good” or “upholding the traditions of the church fathers”

Sin? Repentenace? Rebirth? No one believes THAT anymore .

Agreed. I’ve talked a lot about the mystical experiences in the church over the last year, and these are almost all centered around greater enlightenment or spiritual knowledge. There is little to no emphasis on sin.

The way is narrow and few find it. I wish it were otherwise.

Pingback: James White on the Trinity - Derek L. Ramsey

Pingback: Bart Ehrman on the Trinity - Derek L. Ramsey

Pingback: Attebury vs Charlton on the Trinity - Derek L. Ramsey

Pingback: Bruce Charlton on the Trinity - Derek L. Ramsey

Pingback: Circular Reasoning on the Trinity - Derek L. Ramsey