In “Review: Do we “Resist the devil” or “Resist not evil”?” I opened the series with a discussion on this take on Jesus’ teaching on violence in the Sermon on the Mount:

— Exod. 21:24; Lev. 24:20; Deut. 19:21

But I say to you, do not resist an evil person, but whoever slaps you on your right cheek, turn the other cheek to him also. And let the one who wants to sue you and take away your tunic have your outer garment also. And whoever forces you to carry his things for one mile, go with him two. Give to the one who asks you, and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you. “You have heard that it was said,

— Lev. 19:18

But I say to you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you can be children of your Father who is in heaven. For he causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. For if you love those who love you, what reward will you have? Even the tax collectors do that, don’t they? And if you greet only your brothers and sisters, what more are you doing than the ordinary? Even the Gentiles do that, don’t they? Therefore, you are to be mature, as your heavenly Father is mature.

The post is based in large part on the 21-page paper “A Methodology For Detecting and Mitigating Hyperbole in Matthew 5:38–42” by Charles Cruise which is the subject of this post.

Literal and Figurative

Cruise begins by comparing and contrasting literal and figurative approaches to the interpretation, quickly dismissing the literal approaches. But in doing so, he commits a major category error that threatens to invalidate his entire work.

In Romans 12:17-21, the parallel to Jesus’ teaching on the Sermon on the Mount, Paul quotes Proverbs 25:21-22, which states:

Is this literal or is it figurative? Please pick one.

Are you having trouble answering? That’s because this is a malformed, loaded question.

When the Proverb says “heap burning coals,” this is obviously figurative. If you do what the Proverb suggests, you won’t actually try to set your enemy on fire. So this passage is figurative, right?

When the Proverb says “give [your enemy] food to eat” and “give [your enemy] water to drink” it is obviously literal. These are both things that you can actually do for your enemy. So this passage is literal, right?

When the Proverb says “give [your enemy] food to eat” and “give [your enemy] water to drink” it obviously applies not just to literally feeding him and giving him drink, but this is a figure-of-speech that includes other literal things you can do for your enemy (e.g. clothing him). So it is figuratively speaking of something literal, right?

It is all of these things and more.

The point of this little exercise is to show that a passage can have both literal and figurative elements, including at the same time and in complex combinations. One cannot assume that because Christ used figures-of-speech that he was not also speaking in some literal sense, nor must the whole passage be interpreted in just one way or another, nor can one assume that he was not using figures-of-speech to illustrate literal actions (just as the writer of the Proverb did).

Methodology

…and…

…and…

We’re only on the third page of this paper and already any literal interpretation has been dismissed in only a couple paragraphs. He continues:

Why, I ask, can’t Jesus be speaking figuratively about something that he intends for you to literally do?

The problem, Cruise notes is that one must understand the figurative language—the hyperbole—in order to understand what the figurative language represents:

Cruise’s answer to his own question is straightforward:

Ultimately our critique of Cruise is that his viewpoint resembles the informal (that is, material) Motte-and-Bailey fallacy. He sets out to prove that Jesus used hyperbole—“motte,” the easily defended claim—but uses a reductionist process of mitigation—“bailey,” the hard to defend claim—to arrive at his conclusion.

This is evident in the structure of the paper. Cruise spends three pages on his introduction, six pages on Chapter I: Defining Hyperbole,” and nine pages on “Chapter II: Detecting Hyperbole,” but only two paragraphs on “Chapter III: Mitigating Hyperbole” and just four paragraphs on “Chapter IV: Conclusion.”

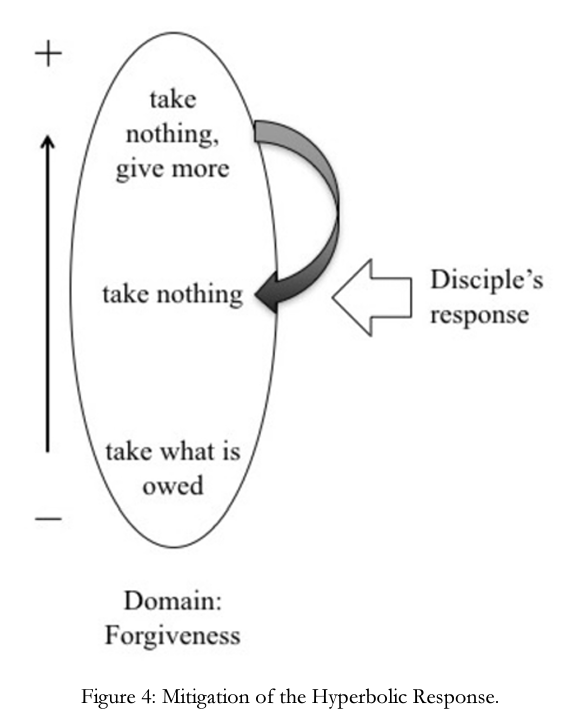

Mitigating Hyperbole

Here is the entirety of Cruise’s third chapter:

That still leaves verse 42 for consideration. By conceptualizing the preceding verses in terms of an economy of giving and taking and by vertically scaling them, the logical connection between verse 42 and the rest of the passage is now exposed. Verses 39b–41 describe giving over and above what is reasonable, and so does verse 42. Though not linguistically connected with the three prescriptions before it, one is able to see why it was placed where it was.

That’s it.

Cruise valiantly proves that Jesus spoke in hyperbole, dedicating most of his paper to that task. That’s the “motte.” Then he simply slips in his “bailey.” Even if we all agree that Jesus used hyperbole…

…we are not obligated to accept this premise.

It all boils down to that one key problem: Why did Jesus use hyperbole? While Cruise’s explanation is logically plausible—a good thing indeed—his stance doesn’t adequately answer that question.

Jesus and Hyperbole

I can freely acknowledge that Jesus spoke in hyperbole, but still come to a very different conclusion that Cruise did. That’s because the use of hyperbole—a rather common figure of speech—does not obligate one to conform to the structure that Cruise describes, nor to discount literal explanations. The example of Proverbs that we opened with is a good example that doesn’t fit with Cruise’s structure, and yet still addresses the same topic.

Jesus’ hyperbole was not stated in a contextual vacuum.

When Proverbs says to feed your enemies, the figure-of-speech doesn’t mean that you should merely refuse to take their food as punishment, nor does it mean that you should not feed your enemies at all. Similarly, when Jesus tells the disciples to give the tunic or an extra mile, he isn’t telling them that they should do nothing. Such a claim makes mincemeat of Jesus’ teaching.

It is rather plain that Jesus wants you to do something positive even if it isn’t strictly literally as he described. So, did Jesus follow up his teaching from the Sermon on the Mount? Yes he did:

“But when the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on his glorious throne. And all the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate them one from another, as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. And he will put the sheep on his right, but the goats on the left.

Then the King will say to the ones on his right, ‘Come, you who have been blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom that has been prepared for you from the foundation of the world, for I was hungry and you gave me something to eat; I was thirsty and you gave me a drink; I was a stranger and you invited me in; naked, and you clothed me; I was sick, and you visited me; I was in prison, and you came to me.’

Then the righteous will answer him, saying, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry and fed you? Or thirsty, and gave you a drink? And when did we see you a stranger, and took you in? Or naked, and clothed you? And when did we see you sick, or in prison, and came to you?’

And the King, answering, will say to them, ‘Truly I say to you, in as much as you did it to one of these my brothers, even the least, you did it to me.’ Then he will also say to the ones on the left hand, ‘Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the fire in the age to come, which has been prepared for the Devil and his angels. For I was hungry, and you did not give me anything to eat; I was thirsty, and you gave me no drink; I was a stranger, and you did not invite me in; naked, and you did not clothe me; sick, and in prison, and you did not visit me.’

Then they will also answer, saying, ‘Lord, when did we see you hungry, or thirsty, or a stranger, or naked, or sick, or in prison, and did not serve you?’ Then he will answer them, saying, ‘Truly I say to you, in so far as you did not do it to one of these least, you did not do it to me.’ And these will go away into the punishment in the age to come, but the righteous into life in the age to come.”

You know what this reminds me of?

Do not repay anyone evil for evil. Think ahead of time how to do what is honorable in the sight of everyone. If it is possible, as far as it depends on you, live at peace with all people. Do not avenge yourselves, beloved, but leave it to the wrath of God, for it is written,

says the Lord.

If the one who hates you is hungry, give him food to eat, and if he is thirsty, give him water to drink, for you will heap burning coals upon his head, and Yahweh will reward you.

In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus said “do not resist an evil person” and then proceeded to explain that we are to return evil with good. Paul, writing in Romans, said the same thing “Do not repay anyone evil for evil.” Did Paul use hyperbole to tell the Christians to simply withhold the right to lex talionis judgment? No, he told us to find a way to live in peace, doing whatever we can do to accomplish this goal. That means feeding your enemy and doing explicit good to him, if that is what it will take.

Jesus used hyperbole to show that you should do whatever it takes to accomplish the goal.

And, perhaps most critically, Paul ties Jesus’ teaching on the Sermon on the Mount with violence:

The absolute minimum level of obedience is to give up your tex talionis right for vengeance.

The idea that the Sermon on the Mount permits violence stands against the rather plain notion that vengeance belongs to God. Not only are you not permitted from exercising your lex talionis rights, but you must personally act. It’s not enough to simply do nothing with your right to judgment, you must go beyond that. That’s the whole point of the Sheep and Goats: God is having his vengeance and rewarding those who did more than merely gave up their rights to retribution.

The idea that the Sermon on the Mount permits violence stands against the rather plain notion that vengeance belongs to God. Not only are you not permitted from exercising your lex talionis rights, but you must personally act. It’s not enough to simply do nothing with your right to judgment, you must go beyond that. That’s the whole point of the Sheep and Goats: God is having his vengeance and rewarding those who did more than merely gave up their rights to retribution.

Yes

But the civil religion of most people that the MGTOW has called tradcons before the red pill term was ever used in the Men’s sphere believes it is one’s moral duty to society to know God wants society’s success at all costs even though this contradicts the story of Sodom and ancient Israel being given over to Egypt, Babylon & being destroyed by Rome in 70A.D. it matters not as God is seen as a cosmic butler that only wants whatever country you live in to prosper no matter what his plans are. Even as JESUS said in their inverted bibles:

”the GREAT nation of our ancestors and it’s people said, “Oh Divine Butler & Cosmic Therapist that WE call God, if it’s our will, take this cup of suffering away from us. However, not your will but our will must be done as so WE sayeth(Luke 22:42)

Or as one highly moral but God rejecting tradcon hipster said some 20 years ago here:

Morals play a large part in religion. Morals are good if they’re healthy for a society like that will be preached by Aaron Renn & Jordan Peterson one day. Like Christianity bro, which is all I know and groove to, the values you get from, like, the Ten Commandments and that JESUS dude sitting on the mount sending good vibes out to that totally righteous crowd. I think every religion is important in its own respect for strict civic servitude. You know, if you’re Muslim, then peaceful Islam is the way for you as W. says homie. If you’re Jewish, well, that’s great too-even dare I say rad and bodacious in my humble opinion. Suppose you’re Christian, well good for you brah. It’s just whatever makes you feel good about yourself while doing the civic religion of the ”GREATER GOOD” like our ancestors did dude.

Pingback: Jesus and Hyperbole, Part 2

Pingback: Constructive Criticism, Part 1 - Derek L. Ramsey