“It depends on what the meaning of the word ‘is’ is.”

— Bill Clinton

I was not a fan of Bill Clinton, nor of his sexual indiscretion. But of all the things to criticize him for, this quote is not one of them.

Bill Clinton is among the most intelligent presidents of all time, with common estimates of his IQ ranging from the high 140s to the high 150s, often just a few points shy of “genius.”[1] That’s quite impressive for a politician. It would not surprise me if he was the most intelligent of all the U.S. Presidents in my lifetime.

The quote above is commonly used to mock Clinton and to portray him as an idiot. But, the joke was always on the critics. The quote actually does a good job revealing his strong language ability, as if his verbal ability to appeal to both the left and the right wasn’t proof enough.

Now, let’s look at what happens when people are not as careful as Bill Clinton:

Why knowledge in the original Greek is helpful!

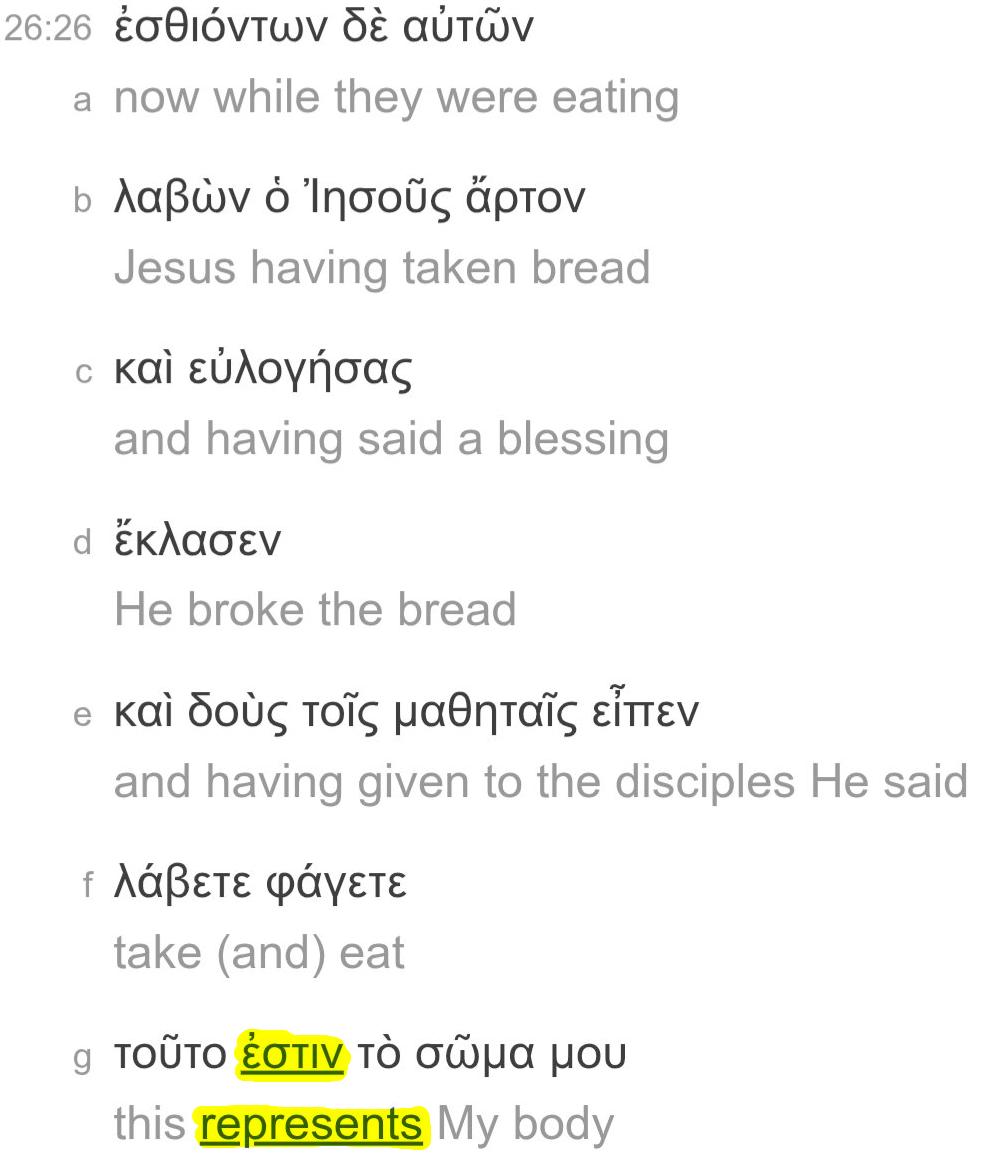

Otherwise, people try to pull this crap, even in interlinear Bibles 😆

έστιν = is.

It is a “to be” verb, a verb of existence!

“Is” means “Is”

In English, the word “is” (or, more properly, “to be”) is commonly part of the class of verbs known by linguists as the copula. Most languages have a copula. In some languages, like biblical Greek and modern English, the copula plays a broadly significant role in the language. The copular verb “to be” has a very wide semantic range, involving many different literal and figurative denotations and connotations, including a variety of non-copular uses. The idea that…

“Is” means “Is”

…is, frankly, a laughably simplistic tautology.

Let’s look at the American dictionary-of-record.

intransitive verb

1 a : to equal in meaning : have the same connotation as : symbolize

“January is the first month.”

b : to have identity with : to constitute the same idea or object as

“The first person I will meet is my brother.”

c : to constitute the same class as

“This book is the authoritative work on the president’s life.”

d : to have a specified qualification or characterization

“The leaf is green.”

e : to belong to the class of

“The fish is a trout.”

“Keeping this room clean is your responsibility.”

These are all the definitions where the word functions as a copula (a linking verb). These are, definitionally, slightly different from the use of the word to indicate existence:[2]

For that we have to look at another category of definitions beyond the (strictly) copular use as a linking verb:[3]

intransitive verb

2 a : to have an objective existence : have reality or actuality : live

“I think, therefore I am.”

b : to have, maintain, or occupy a place, situation, or position

“The book is on the table.”

c : to remain unmolested, undisturbed, or uninterrupted —used only in the infinitive form

“Let him be.”

d : to take place : occur

“The concert is today.”

e : to come or go

has already been and gone

has never been to the circus

f : (archaic) belong, befall

… to thine and Albany’s issue be this perpetual.

— William Shakespeare

Existence is just one of a number of possible (strictly non-copular) meanings.

But we don’t have to stop there. The word also has other linguistic uses:

auxiliary verb

1 : used as an auxiliary (see auxiliary entry 2 sense 3) with the past participle of transitive verbs to form the passive voice

“The money was found.”

“The house is being built.”

2 : used as the auxiliary of the present participle in progressive tenses expressing continuous action

“He is reading.”

“I have been sleeping.”

3 : used with the past participle of some intransitive verbs as an auxiliary forming archaic perfect tenses

“… Christ is risen from the dead …”

— 1 Corinthians 15:20 (Douay Version)

4 : used with to + infinitive to express futurity, arrangement in advance, or obligation

“I am to interview him today.”

“She is to become famous.”

5 : used in the uninflected form be in African American English and to varying degrees in some other varieties of English to indicate that an action or state is habitual or frequent.

“I be singing in the shower.“

If you are a native English speaker, you can probably trivially understand and distinguish between fifteen of the sixteen different uses of the verb “to be” without even a conscious awareness that you are doing so. A great many English speakers are completely unaware that “is” (in its various forms) can be used in so many different ways, and they’d be hard pressed to identify all of the different ways they use the word without even trying.

Now, the Bible is even more interesting. The Greek verb eimi is used 2,479 times in the New Testament. It is the most common verb in the New Testament, making up almost 1.4% of the total words. Moreover, four of the top five verbs in the NT have copular or semi-copular uses or otherwise correspond to the English word “to be.”

In the KJV version of Matthew alone, eimi is translated in the following ways:

- are, am, is, was, were, (will, might) be

- being

- came about, comes

- had

- remain, remained

The NASB translates it in these ways in the New Testament:

And if you thought the English definition was long and complex, Thayer’s Greek Lexicon gives six different major categories, twenty-six different definitional uses, and a whopping seventy-six different specific definitional forms. And, as if that were not enough, there are twelve related Greek words that function linguistically in a similar fashion.

What might really eat you up is that the verb “to be” can be explicitly elided (missing) from a sentence, yet be implied by the grammatical and linguistic context! For example, in English:

[Are] you hungry?

Yes [I am].

This pattern of verb elision is found in many languages, not just English.

The English dictionary contains only the denotations of the word “to be.” It does not include all of the numerous different connotations, nor does it exhaust all the semantic nuance achievable through the use of different tenses or figures of speech. To wit:

Your problem is one of linguistics.

Metaphor, analogy, synecdoche, metonymy, etc. are all features of predication.

Literal identity is by no means the only option.

Thayer’s Lexicon’s 76 unique uses of just one of Greek’s copular verbs gives us a small taste of the linguistic depth encapsulated in the deceptively simple verb “to be.”

Now, imagine trying to translate a hundred different uses of a dozen ancient Greek words (which may only be implied by the text!) accurately with the correct denotations and connotations into modern English. That’s quite the challenge. And it’s far, far from:

“Is” means “Is”

Bill Clinton was asked a fairly mundane loaded question, and he responded as an intelligent man should respond:

If the—if he—if ‘is’ means “is and never has been,” that is not—that is one thing. If it means “there is none,” that was a completely true statement.

— Bill Clinton

Like ancient Greek, the verb “to be” is highly ambiguous[4] and contextual in English. Thus, when one is accused of (or, in the case of Clinton, guilty of) wrongdoing, language precision is very important. The same is true in matters of theology.

Footnotes

[1] It is common to say that a “genius IQ” is 160 or greater. However, true genius ability is not best defined by a specific IQ score but concurrently or retroactively according to the exceptional creativity and performance of the geniuses themselves. There are, after all, geniuses with IQs less than 160 and many people with IQs greater than 160 are not geniuses. An IQ of 160 remains, by definition, rare.

[2] While only some meanings of the Greek and English verb “to be” are strictly copular—linking verbs— in linguistic terms, all of them are ontological, pertaining to the metaphysics of being. The various definitions of “to be” (whether copula, semi-copula, or non-copula) refer collectively to aspects of being, existence, and reality. Thus, while linguists differentiate between the copula and existence, this is a somewhat arbitrary categorization based on external philosophy and other conventions.

For example, we can say…

“He is blue.”

…and…

“He is [in existence].”

…while intuitively viewing the copula (the first sentence) and existence (the second sentence) as merely slightly different variations on the same ontological theme. Both are answers to the question “What is he?”

Different languages may (Hebrew, Greek, Latin, German, English, Russian, Arabic, Chinese) or may not (French, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, Irish, Japanese) combine the idea of existence and the linguistic function of the copula in a common word. Doing so is optional, but nevertheless quite natural for those that choose to do so.

Similarly, some languages, like Spanish, divide the copula itself into more than one word, each with its own distinct sense (e.g. ‘ser’ and ‘estar’), such as dividing between (permanent) essence and (temporary) state. Just as grouping or splitting existence and copular function is arbitrary, so too is grouping or splitting linking verbs arbitrary.

Regardless of which different approach a language ultimately chooses, this does not change the inherent ontological compatibility of the copula and verb of existence. Linguistic convention and philosophy are, essentially, orthogonal concerns.

[3] The quote is technically incorrect. Strictly speaking, the verb ‘to be’ in the phrase “this is my body” acts grammatically as a copula—a linking verb—not a verb of existence.

[4] Despite its inherent ambiguity, people not only freely choose to use the verb, but it is the most common verb in many languages. It is often selected by speakers and writers even when a more precise verb exists!

A quibble – “estimates of his IQ ranging from the high 140s to the high 150s, often just a few points shy of “genius.””

You did put “genius” in scare quotes – and justifiably, because the vast majority of people with the highest IQs (and with the highest general intelligence) are Not geniuses. Probably the best demonstration of this is Lewis Terman’s California cohort study of the highest IQ kids in California ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Terman ) did not include any recognized geniuses – although, on average, the cohort was very successful across a wide range of life outcome measures.

(Their main failure was in fertility, which was much below average, but especially in women – the highest IQ women averaged approx 0.5 children at a time when the average was about 3 or more. And this was a century ago, before the sexual revolution had bitten.)

There were a couple of geniuses tested by Terman that were missed, did not reach the threshold high IQ – probably the kids had an off day, or under-performed for a wide range of other possible reasons – the most egregious of these missed, was the genius-for-sure Claude Shannon – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claude_Shannon .

On the other side, I personally have never been convinced that super high IQ measurement is a requisite of genius – or even usual (except in certain abstract subjects like mathematics and physics).

Since IQ is a relative measure (referenced to a specific population) and an ordinal scale, the necessary IQ for a genius can only be expressed relatively.

Fair. I should probably just adopt your definition of genius and use other descriptors other than ‘genius’. After all, the scare quotes are there in the first place because I’ve read your work on the subject.

The colloquial way that I am using it is quite common among average men. It has the advantage of speaking in a way that anyone will more-or-less understand. But it’s also inaccurate, as you note. I could be using more precise language.

Footnote added.

I am very unsure about the IQ of public figures – not least because they often get attributed with achievements that are not their own, and I suspect corruption to be at work in some the the apparently illustrious CVs.

But I was struck by several people who have said that Richard Nixon was exceptionally intelligent – notably Milton Freidman said Nixon was by far the most intellectually capable of the high level politicians and presidents he had interacted with – extremely quick on the uptake.

Another unpopular politician who was exceptionally intelligent (and able) was Herman Goering. Of the Nazi officials IQ tested in the Nuremberg show-trials – he was the top scorer; and this was despite debilitated health and decades of drug usage. I think the score was 137 – but I’ve no idea how they calibrated or standardized that number.

I am very dubious about the meaning of ultra-high IQ numbers – so much depends on the way a test is structured, and the weight given to the verbal, mathematical and visuo-spatial subcomponents – because the correlations between these break- down with increasing IQ.

(Also, genius is characteristically lop-sided in its abilities – and this may be part of what makes a genius. Ed Dutton found surprisingly far above average rates of serious prematurity and light-for-dates smallness among geniuses – it may be that the creative aspect of genius actually derives from some degree of brain stress or pathology.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/Sent-Before-Their-Time-Prematurely/dp/0645212636?crid=15DLCVIKDM9R3&dib=eyJ2IjoiMSJ9.Cs9XRB8Dq08OBSp8DvLqsJWcSGUeovbU51-6mWlzLpO0x3ikIf5i5uYB4bzH34ezBV71KqSrUKYBsBLkenzDcw.iEacs28atdgdcaoXpg8hiw3dE-zsPRIdXuFiVxocOmc&dib_tag=se&keywords=edward+dutton&qid=1767877981&s=books&sprefix=edward+dutton%2Cstripbooks%2C102&sr=1-17&xpid=Bkpi18hdyCxxb)

Also, it is literally impossible to generate a valid standard distribution curve for the highest levels of IQ, due to the inability to get random population samples, and the extreme percentage rarity (by definition) of the people at the highest level. Lacking a truly valid standard distribution curve, all cited IQ measures – between studies, between nations, as well as across time – are much more approximate than mostly realized.

IQ just became a way for many people to feel good about themsrlves, and lord it over the rest of us. Even in the ‘sphere. We equated “high / higher IQ ” as “good” and anyone who didnt have one as “bad” or “shutup and listen to the smsrt men!”

Notice most men in the sphere claim how smart or intelligent they are? When everyone is a genius. None are.

High IQ dirsnt mean “he makes good decisions”. High IQ doesnt mean “wisdom” nor does it give you a “free express pass” to sit at the right hand of God

IQ was once a framework. Today we doom people to digging ditches if it isnt above 100, and excuse geniuses for being “lazy” because “low IQ proles ruined everything”

You are so smart? So talented? So gifted? So articulate??? Why dont you lead????

A community doesnt need 50 nuclear scientists, 100 lawyers who scored perfect on the bar. It doesnt even need 10 surgeons. It needs people with common horse sense….regardless of the IQ to put the tools away, clran up, maintain.

Never seen so many “brilliant” and “high IQ men” and yet cant control their sex drive, cant do work that is beneath their supposed intellect and seem to lord it over the rest of us about how brilliant they are

Lastmod,

Small differences (of a point or two) in IQ between populations is incredibly meaningful. But those same small differences between individuals hardly matters at all. Siblings will differ by many points, but often stay mostly within a standard deviation (i.e. 15 points). Individual differences become a bit more noticeable once the difference is at least 1 SD, or 15 points.

The error is thinking that relatively small differences in IQ matter all that much to individuals. Individuals places too much weight on precise numbers.

Peace,

DR