Part 1 — Introduction

Part 2 — The Council of Nicaea (325)

Part 3 — The Council of Constantinople (381)

Part 4 — The Council of Ephesus (431)

Part 5 — The Council of Chalcedon (451)

Part 6 — Leo

Part 7 — Conclusion

What theological statement will get you in this position?

I recently saw this clickbait question. The answer, for me, is obvious: it is the theological question of Papal Roman Primacy in the early and late 4th century, a topic I have briefly written about in the past. For me, the most interesting theological question is, in fact, an historical question. I find this most interesting because of the absurdity of a religion dictating what history must have been, rather than what the historical evidence itself says actually occurred.

This is not merely a theoretical pursuit. In general, whenever I raise this question, it is met with hostility, condemnation, and either banishment or a loss of readership (i.e. reverse banishment; isolation). The metaphorical axes and knives really do come out. Some ideas just cannot be discussed in polite settings. But this is an ideas blog, where we don’t cater to personal feelings.

So today we are going to discuss Lawrence McCready’s article “Papal Primacy in the First Councils” from the Unam Sanctam Catholicam blog. I’ll be responding to the 2022 version (which was edited in content from the 2011 original) that I accessed in 2025. This represents a typical Roman Catholic apologetic. We’ll go over it point-by-point in a multi-part series.

The Charges

It is standard fare in the apologetical work of Protestants and Eastern Orthodox to assert that the doctrine of the primacy of the See of Rome was a medieval invention. A corollary of this assertion is the belief that, in the patristic era, the bishops patriarchal sees all interacted basically as equals with no concept of a Roman primacy until the early medieval era. How can a Catholic answer these charges?

The medieval period—known as the Middle Ages—extended from the 5th to the 15th centuries. Technically, Roman Catholicism arose in the later half of the 4th century, so it isn’t strictly speaking purely medieval, but the bulk of the development did occur in medieval times. So the widespread belief by Protestants and Eastern Orthodox that Papal Roman Primacy is medieval is largely correct, even though it originated in the late 4th century.

In any case, it’s worth noting that McCready is implicitly acknowledging that this is not some fringe belief held by a few weirdos on the internet. The belief that Papal Roman Primacy is a medieval development has been held by a great many over the centuries.

McCready has also fairly summarized the early church position: that the bishops were treated more-or-less as equals on theological matters.[1]

An Tentative Response to the Charges

Most Christians are totally unaware that the historical evidence for the Petrine primacy is quite rock-solid (pun intended). Many would assume there are good arguments that can be made either way, particularly among the Eastern Orthodox. Of course, neither Protestants nor Eastern Orthodox have an ‘”official” view as to how the papacy fits in with the historical testimony, but they all agree the papacy is a serious doctrinal error that crept in over the centuries. The goal of this article is to show that, contrary to popular belief, the earliest Ecumenical Councils strongly indicate the Bishop of Rome was recognized as Supreme Head of the Church (1). Given this fact, both Protestants and Eastern Orthodox are ultimately forced to admit the Church fell into apostasy, since the papal primacy is testified to by an agreed upon historical Christian witness. All quotes in this article are from virtually undisputed primary historical sources.

The historical evidence for Petrine primacy is not, in fact, “rock-solid.” The irony is that most Roman Catholics are totally unaware of the historical evidence against Petrine Primacy. Many simply stick their head in the sand and refuse to examine the issue. In reality, there are not actually good arguments on both sides. Other writers may be polite about it, but here you will be told the truth: the argument is lopsided.

As we go over McCready’s article in this series, we will quickly demonstrate this. We will contest that the Bishop of Rome was recognized with any special authority. In fact, we will show from undisputed primary sources that the Bishop of Rome was not even one of the main Bishops of the church in terms of geographical relevance.[1] We will show that McCready grossly misunderstands and/or misrepresents the “undisputed primary” historical record.

In short, we will show that the church fell to apostasy in the late 4th century as Roman Catholicism arose in its place, since Papal Roman Primacy is not testified by the early historical Christian witnesses.

But before we move along, pay close attention to one thing McCready said:

Of course, neither Protestants nor Eastern Orthodox have an ‘”official” view as to how the papacy fits in with the historical testimony, but they all agree the papacy is a serious doctrinal error that crept in over the centuries.

This reveals an important potential bias: the presumption that the objections to Papal Roman Primacy should, properly, agree and be unified in order for the objection to be valid. This is does not logically follow. In fact, a lack of specific agreement on why it is a doctrinal error is mostly irrelevant and shouldn’t even have been mentioned.

This reveals a possible bias towards the presumption that unified hierarchical authority is required to determine what is true. You can see the Roman Catholic bias in the implicit desire for an “official” proclamation and the implied discontent with it being absent. But, the historical record stands on its own regardless of whether authorities agree. In apologetics, appeals to expertise and authority—including Papal authority—are logically fallacious.

About That Footnote

(1) I am indebted to Fr James Loughlin’s masterful article he wrote in 1880 in the American Catholic Quarterly Review titled “The Sixth Nicene Canon and the Papacy.” This article is my attempt to summarize his major arguments.

The problem with relying on expertise is that your argument is only as good as the expert you are relying upon. If the expert makes an error, you will end up perpetuating that error even as you confidently assert your position. Ironically, Loughlin identified this very problem:

An error, be it ever so common, is an error still;

James Loughlin’s article is anything but masterful because he falls victim to very pitfall he warned about. Here is a brief summary of the problem:

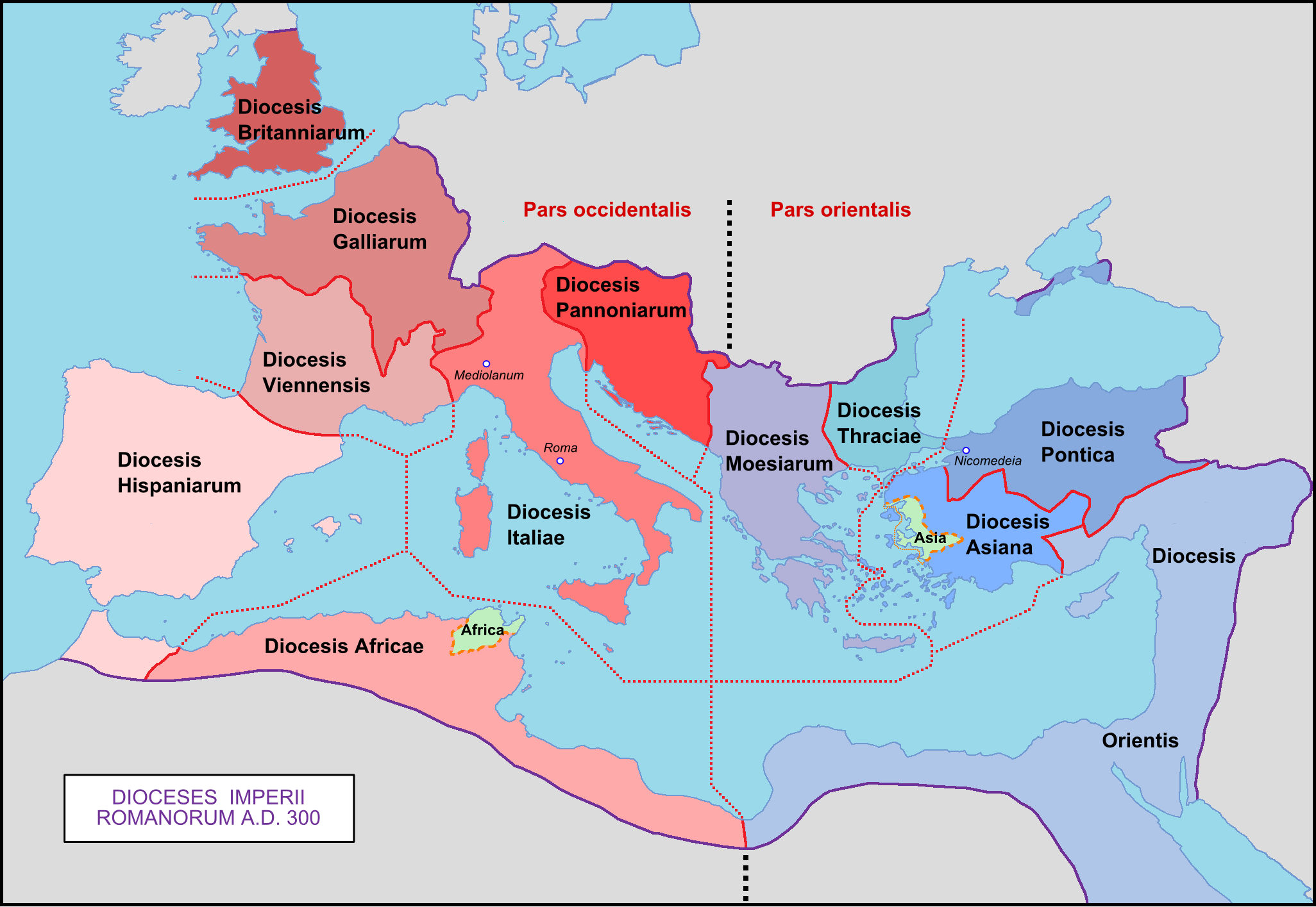

I have read Bellarmini, Justellus, Hefele, Schaff and Loughlin on Canon 6 of Nicæa, and to man, they relied on Jerome, Rufinus and Innocent I on the geographic order of the Roman Empire at the time of the council, and yet Jerome, Rufinus and Innocent I were catastrophically wrong, as they deferred to the late 4th century geographic order to understand a very different geographic order that existed in the early 4th century. It is not scholarly to defer to them in their errors.

Thus, I am happy to read the experts. They are often helpful. But they often err, and so often capitulate to Rome and defer to late 4th century novelties to understand the first three centuries of Christianity, that they simply cannot be considered the final say. Where they are helpful, I am happy to seek their aid. Where they are in error, I am also happy to point it out.

The Sixth Nicene Canon and the Papacy

Writing in 1880, Laughlin lays out the issue, as he sees it:

The Protestant historians and controversialists, with a few honorable exceptions, will reply that whereas the Bishop of Rome, from being a simple bishop, like any other, had succeeded, before the date of the Council, in imposing his authority upon the bishops in his vicinity, the Council thought it proper to permit him to retain his usurped dominion; a course which they are free to deplore, since it encouraged the “ambitious Pontiff” to persevere in his fixed design of enthralling the Christian world.

This is a factual error, an invalid inference.

In 1880, much of the historical evidence was not commonly known or available. It does not appear, for example, that Loughlin knew about or had studied the Laterculus Veronensis, the Notitia Dignitatum, or the Codex Theodosianus. If he had, he would have realized that the Diocese of Egypt didn’t exist at the start of the 4th century but did exist by its conclusion, having been established sometime between 370AD and 378AD[2], more than a generation after the Council of Nicaea in 325AD.

Loughlin, along with most Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestants, was—in 1880—unaware that Rome was not the chief Metropolitan of the Diocese of Italy. That honor went to Milan. Rome was, in fact, a lesser geographical entity within the both the political sphere of the Roman Empire and the ecumenical sphere of the church.

Loughlin gives this translation of Canon 6…

“Let the ancient usage throughout Egypt, Libya, and Pentapolis be strictly adhered to, so that the Bishop of Alexandria shall have jurisdiction over all these; since this is also the custom of the Bishop of Rome. In like manner, as regards Antioch and the other provinces, let each church retain its special privileges.” (Canon 6)

…ultimately concluding that these provincial references referred to the church deferring to the Pope’s decision:

In the Catholic system, then, “Alexandria, Antioch, and the other eparchies,” were exercising prerogatives which belonged, natively, to the chair of Peter, and we are forced to the conclusion that they and the Council were as sensible of this as we are ourselves. Therefore,the clause in question can bear no other interpretation than this: “Alexandria and the other great Sees must retain their ancient sway because the Roman Pontiff wishes it.” Understood in this sense the (epeide) places the archiepiscopal thrones on the firmest — and indeed the only firm-foundation. Why should we deem the Fathers of Nicaea either less “Roman” than ourselves, or less capable of comprehending their strongest argument in favor of Alexandria?

It may be objected that this argument would have no weight with Protestants. What of that? Are we to abandon our old standard of interpretation, our “Catholic analogy,” because, for-sooth, we cannot induce “those who are without” to view things from our standpoint? Let our adversaries prove that our interpretation is false; for the burden of proof is upon them.

The Council of Nicaea said nothing in Canon 6 about “the chair of Peter” or its supposed prerogatives. You can also read the above translation and compare it to this statement (already quoted above)…

…the Bishop of Rome, from being a simple bishop, like any other, had succeeded, before the date of the Council, in imposing his authority upon the bishops in his vicinity…

…to conclude that the Canon says no such thing.

These are unwarranted assumptions by Laughlin. But this is no matter. We can freely take up the burden of proof without complaint and show that his interpretation is, indeed, false.

Laughlin mentioned Egypt over twenty times in his article, but made only a single reference to Oriens. In doing so, he revealed his ignorance of history.

The Bishop of Alexandria had been, from time immemorial, every inch a patriarch throughout his vast domain. The Bishop of Antioch enjoyed a similar authority throughout the great diocese of Oriens. Their jurisdiction was immediate and ordinary, and there no difficulty in defining its nature and the limits within which it was exercised. If, therefore, the Council had”illustrated the sort of power,” which it accorded to the Bishop of Alexandria, “by referring to a similar power exercised by the “Bishop of Antioch, then the term of comparison would be clearly intelligible; because both were patriarchs, with pretty much the same sort of power and the same extent of territory. But who has ever defined satisfactorily the limits and nature of Rome’s patriarchal sway?

This is simply historically incorrect. It reveals, catastrophically, Laughlin’s ignorance of history.

After the Diocletian reorganization at the end of the 3rd century and prior to (at the earliest) 370AD, Alexandria and Antioch were both within the Diocese of Oriens. Only after (at the latest) 378AD, was Alexandria contained within the separate Diocese of Egypt.

Far from being from “time immemorial,” at the Council of Nicaea in 325AD, neither the Bishop of Alexandria nor the Bishop of Antioch held sway “throughout the great diocese of Oriens.” In fact, the Diocese of Oriens was shared through provincial division between no less than three Metropolitans: Antioch, Jersualem, and Alexandria.

Prior to the split of Oriens, Antioch was given the primacy, while Alexandria and Jerusalem were given lesser geographical cuts within the Diocese. Only after the split (between 370AD and 378AD[2]) could it be said of the Bishop of Alexandria that he was “every inch a patriarch throughout his vast domain.” But, of the Bishop of Antioch the same could not be said, for he had never “enjoyed a similar authority throughout the great diocese of Oriens” because he had to share it with the Bishop of Jerusalem. Jerusalem’s jurisdiction was smaller and limited, but it was nevertheless its own with Oriens and not subject to Antioch. In point of fact, at no point in the 4th century did the Bishop of Antioch ever hold sway over the whole of the region.

Prior to the split, there was nothing immediate and ordinary about the jurisdiction of Antioch and Alexandria. Even as the political division was now made up of dioceses, the church was still stuck using older provincial language because there were three Metropolitians within one Diocese. The council had to clarify Alexandria’s jurisdiction precisely because it was not immediate and ordinary, because there was a difficulty in defining its nature and limits. The reality was exactly the opposite of what Laughlin claimed.

However, by 381AD at the Council of Constantinople, it was now immediate and ordinary to define Alexandria’s jurisdiction in terms of the now existing Diocesian boundaries (i.e. the Diocese of Egypt now being separate from Oriens). But, in 325AD at the Council of Nicaea, it was an historical impossibility to define the jurisdiction in simple diocesian terms, because Antioch and Alexandria existed in the one Diocese of Oriens.

Laughlin falsely assumed that the boundaries that existed in 381AD also existed in 325AD. This was an historical impossibility.

But what of Rome? Why was Rome cited as legal precedent? Because, like Oriens, Italy contained a conflict between multiple Metropolitans in one Diocese: Milan and Rome. Just like Alexandria was given a restricted domain within Oriens, so too was Rome given a restricted domain within Italy.

Alexandria was not assigned its domain because the Roman Pontiff wished it, rather it was assigned its domain because the Bishop of Rome was also granted limited sway. Neither had primacy.

As an expert, James Loughlin failed miserably to accurately describe the historical record. As we continue this series throughout this week and the next, we’ll see more about how this error propagated and eventually turned into Papal Roman Primacy.

Footnotes

[1] The Bishops were equal in theological authority among themselves, but not in political power. They were similar in that they each had sole governing authority within their geographical domain. But, quite obviously, not all domains were geographically equivalent. Some were physically larger, while others contained a larger population. For example, the Bishop of Antioch’s domain was much larger than the Bishop of Jerusalem’s. The former’s domain pertained, by default, to the whole of the province (or diocese) while the latter’s domain pertained to a smaller restricted territory selected out from the whole. Notably, the prominence of one’s geographical domain did not correspond to theological prominence.

[2] Due to this being so far in the past and with much documentation lost, the dating is somewhat uncertain. Edward Gibbon suggested in “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” (Editor: George Davidson; Kindle Edition, location 3290) that Oriens split in c.360, “about” 30 years after the establishment of Constantinople in 330. A.H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire 284-602, Vol 3, p.390 gave a somewhat later estimate:

However, using the evicdence from primary sources gathered by Clyde Pharr (in The Theodosian Code and Novels, and the Sirmondian Constitutions, 1952, p.351,356), the change must have happened no earlier than 370 (or maybe 373) and no later than 383AD. See Timothy F. Kauffman’s podcast notes (see the PDF here):

But it must be earlier than 383, because the Council of Constantinople (381) was already using the new diocesan arrangement.

Wikipedia gives further support by citing a date of c.381 per Palme, Bernhard (2007). “The Imperial Presence: Government and Army” (in Bagnall, Roger S. (ed.). Egypt in the Byzantine World, 300–700. Cambridge University Press. pp. 244–270), while the “Oriens” entry in the Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Vol III. (Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991), Oxford University Press. pp. 1533–1534) says that the split occurred under Valens’ reign (364–378).

This suggests that the split occurred between 370 and 378.

Nobody who was at Nicea mentions any canons, only the creed. Ergo, rhe canons of Nicea were invented at a later council and retrojected. Probably at Ephesus or Chalcedon. I firmly believe the canons were invented at least a century later. So the line about it being “ancient custom” for Alexandria to rule in that way, and comparing it to Rome, does not prove it was done prior to Constantine but rather shows the forgers of the Nicene canons at Chalcedon or Ephesus spoke anachronistically. It was “ancient custom” of one century by their time, but at Nicea the Emperor had just begun the Patriarch system with the last 10 years.

Jeff,

Welcome and thanks for your comment.

The way that the 5th century Bishops of Rome Zosimus, Celestine, and Leo spoke of Nicaea, they clearly and unambiguously conflated Nicaea with the later 4th century council of Sardica (and, maybe, Constantinople). Does this conflation prove that Nicaea was invented in the 5th century? I don’t think so. After all, the other Bishops cited what we now know as the canons of Nicaea without any obvious conflict or error.

It is only Rome’s Nicean canons that were clearly fabricated (as we’ll discuss in part 6 on Monday morning). Your explanation can only apply to Rome’s version of events, not to the version told by Rome’s opposition. Read the section on the Apiarius controversy as written by Charles Gore in “Leo the Great” here (see, especially, pages 111 to 115). In particular:

However much, then, the canons of Sardica may at Rome have been regarded as an appendix to those of Nicaea, no pope after could, without deliberate misquotation, quote the appeal-canon as having Nicene authority. He could not plead ignorance after this clear demonstration. It must therefore be admitted that Leo in urging, as he constantly did, Nicene authority for receiving appeals from the universal Church, was distinctly and consciously guilty of a suppressio veri [lie by omission] at any rate, which is not distinguishable from fraud. Of this crime we cannot acquit him;

…

The “custom of the Roman Church” is a strange plea to urge on Leo’s behalf; [but] it is the only one that can be urged.

So, you are correct that Rome’s Nicean Canons were a fabrication (which contradicted the real Nicaean Canons), but we need much more than an Argument from Silence for your claim about the whole church to be convincing.

No, read what the canon says:

This can only make sense if it was written around 325AD.

The Pre-Diocletian civil arrangement was provinces that included the province of Egypt, the province of Libya, and the province of Pentapolis. After Diocletian, there was no ruling civil province of Egypt, Libya, or Pentapolis, there was now a ruling civil diocese of Oriens that incorporated all the previous provinces and more under a single civil Vicarius (and with Prefects under him).

But the church now had a problem with multiple ecclesiastical Bishoprics within one civil diocese that had been created by Diocletian and the Diocese of Oriens. The church couldn’t have three Vicar-equivalents in one Diocese, so to resolve this conflict, the church had no choice but to retain the pre-Diocletian provincial language. It made Bishop of Antioch the ecclesiastical equivalent of the civil Vicar, and Bishops of Jerusalem and Alexandria the ecclesiastical equivalent of the civil Prefect, bringing the ecclesiastical church organization in line with the civil organization.

As you note, it had only been 10 years since the Emperor had instituted the Patriarch system, so Nicaea was required to fix this pretty quickly after it became a problem. The timing makes sense. But, the wording makes no sense if the Canons of Nicaea were a future fabrication.

Now, pay attention to the two words used for “ancient customs” and “customary.” As just discussed, the former refers to the old, ancient Pre-Diocletian arrangement. But, the latter refers to a newer, not-ancient arrangement.

The Pre-Diocletian arrangement had granted separate ecclesiastical provinces to Rome and Milan that corresponded to the Pre-Diocletian civil arrangement. In the ancient past, there was no conflict. But after the civil reorganization in the 290s, Milan took the Diocese while Rome did not. So, while Alexandria and Antioch could not resolve their differences, the custom of Rome took place naturally. Rome simply accepted its limited jurisdiction without complaint. So a few decades later in 325, the Council of Nicaea was able to cite Rome in the dispute between Antioch and Alexandria.

The key is the ancient (pre-Diocletian) custom of Alexandria and the recent (post-Diocletian) custom of Rome.

Peace,

DR

Pingback: Who Writes the History Books? - Derek L. Ramsey