This is the third in a five-part series on head coverings. See the index here.

There are so many ways to discuss 1 Corinthians 11:2-16, it is hard to know where to begin. Paul wrote it in a chiastic structure…

A. v. 2–3

B. v. 4–7

C. v. 8a

D. v. 8b

E. v. 9a

F. v. 9b

G. v. 10

F’. v. 11a

E’. v. 11b

D’. v. 12a

C’. v. 12b

B’. v. 13–15

A’. v. 16

…so we could discuss each part of the chiasm from the inside out or from the outside in. Or we could discuss each chiastic pair together…

A. v. 2–3 + A’. v. 16

B. v. 4–7 + B’. v. 13–15

C. v. 8a + C’. v. 12b

D. v. 8b + D’. v. 12a

E. v. 9a + E’. v. 11b

F. v. 9b + F’. v. 11a

G. v. 10

…comparing and contrasting each. Or we could just read it linearly and imagine that Paul intended it to be understood that way.

I really don’t know what is the best way to inform readers.

I think I’ll try something different: starting with the clearest parts and trying to reason from the clear parts to the unclear parts. So, I’ll start by exegeting only the most clear and obvious verses: 10, 12, 15(b), and 16. Then in Part 4, I’ll discuss the whole thing. This reflects the hermeneutic method of exegeting the unclear by using the clear, rather than the other way around.

We’ll start here, in verse 10. It is the middle of the chiastic structure. It forms the central thrust of the argument Paul is making. Regardless of what else you might say, the meaning of this verse in particular sets the tone and focus for everything that comes before and after it. It is the anchor or frame of the entire passage.

Therefore, the woman has an obligation to have a symbol of authority on her head, because of the angels.

You might wonder why I’m starting the discussion on clear and obvious verses with this verse, because this isn’t particularly clear or obvious. Well that’s actually true: it isn’t particularly clear in English. But it is is much clearer in Greek.

First, in English, the phrase “a symbol of” does not exist in the original Greek text. It is, at best, an implication (which may beg the question), and, at worst, a later textual corruption. For example, in his homilies on 1 Corinthians, John Chrysostom explicitly misquoted the verse by adding the gloss “symbol of” (or “sign of”). This usage does not exist in the manuscripts of 1 Corinthians.

Second, In English, the phrase “ought to have authority” is passive, but in Greek it is active (it is actually a combination of two active verbs). The passive sense means that the authority acts upon the woman, while the active sense—the one Paul used—means that the authority belongs to the woman.

Fee also comments in n. 112 that

Nowhere is this particular grammatically active phrase ever used in a passive sense, not in the Greek New Testament, not in the writings of Paul, not in the Greek Septuagint, nor in any other extant contemporary (or older) Greek literature.

The tastefully named W. M. Ramsay concurred:

Citation: W. M. Ramsay, The Cities of St Paul (New York, 1908), 203

This is a scathing, but accurate, criticism.

Third, Paul used a similar grammatical construction a few chapters earlier:

But he who stands steadfast in his heart (being under no obligation, but has control over his own will) and has decided in his heart to keep his own virgin daughter will do well.

Here is a brief summary:

| Feature | 1 Cor 7:37 | 1 Cor 11:10 |

|---|---|---|

| Verb form | ἔχει (indicative) | ἔχειν (infinitive after ὀφείλει) |

| Object | ἐξουσίαν (authority) | ἐξουσίαν (authority) |

| Prepositional phrase | περὶ τοῦ ἰδίου θελήματος (“over his own will”) | ἐπὶ τῆς κεφαλῆς (“on her head”) |

In both cases, the grammar describes someone exercising personal authority over something that is theirs (i.e. his will and her head).

The verb form does not change the subject of the verb. The indicative of the first means “[he] has [authority],” while the infinitive form of the second means “[she] ought to have [authority].” The latter is describing what should be, rather than the former’s what is. In both cases the authority rests with the subject, not a third party.

The difference in preposition is not massive either. Both are in the genitive case, indicating relationship, association, or possession. The preposition in 7:37 can mean “over” or “concerning” while the preposition in 11:10 can mean “upon,” “over,” or even “concerning.” In context the former says that the man has authority concerning something that belongs to him, while in the latter it refers to the realm or domain over which she has authority.

There is no grammatical basis for assigning the authority to someone other than the subject of the active verbs, such as to the husband instead of the wife. The only reason this has become unclear is because the Greek is often mistranslated or misquoted—as though Paul had used a passive construction—by commentators presupposing a particular theology.

Neither Paul nor any other extant contemporary Greek writer ever used this novel interpretation of a common grammatical structure to imply subjection to another. As we discussed in Part 2, the earliest example of ‘authority’ being misquoted as ‘veil’ was the Valentinians—a Gnostic sect—nearly a century later. Similarly, the earliest example of ‘authority’ being misquoted as ‘a symbol of authority’ occurred around 400 AD in the writings of John Chrysostom.

NOTE: The popular misquotation “a symbol of authority” is a clear and obvious—and arguably the only—attempt to overtly bypass the inherent grammatical contradiction with the pro-head covering view. The argument goes: “A woman does not actually possess authority, she has a symbol of authority. Her domain is her cloth head covering, the symbol itself, not the authority that the symbol represents.” By misquoting it—inserting words that Paul does not use—the active statement of personal authority becomes a passive symbol of subjection. If the text is allowed to speak for itself, the completely opposite meaning is plain and obvious. This is why Chrysostom, a native-Greek speaker, didn’t see a problem with the grammar: he was working with—or responding to—a strawman instead of the original wording.

Ultimately, the entire argument in favor of mandatory head covering rests on an unprecedented grammatically novel interpretation, a couple of ancient misquotations, and a doctrinal tradition not found in scripture.

In summary, a proper translation should read something like this:

This brings us to the final question: why is Paul talking about angels? What could he possibly mean by such a seemingly obscure reference. To answer that question, we should first see if there are any contextual clues. So, had Paul previously said anything about angels? It turns out he did only a few chapters earlier:

Do you not know that we will judge and administer angels? How much more, then, things that pertain to this life?

The reasoning is quite simple. If women will be judging angels, then of course they can judge over the far more simpler things that pertain to this life, such as what she puts—or does not put—on her head. Because she’ll be judging angels—who currently answer to no one but God himself—she can obviously judge for herself whether to wear a cloth on her head or simply leave her head bare. Here is an appropriate paraphrase:

For as the woman is from the man, so is the man also by the woman, but all things are from God.

First, the relationship between male and female is reciprocal. Neither the woman (or wife) or the man (or husband) has any advantage on account of their birth. Whether you are a man or woman, you come from both a man (your father; Adam) and a woman (your mother; Eve). It’s basic biology, quite obvious from nature.

Second, regardless of one’s birth, everything comes from God. Neither man nor woman is closer to God.

When it comes to covering or uncovering, what is the advantage to being male? To being female? There is none.

…for her hair is given her for a covering

Paul explicitly states that a woman’s hair qualifies as “a covering.” In Greek, this is the word for a mantle. A mantle sometimes looks like this:

As noted, common synonyms include a cloak, cape, shawl, wrap, or stole.

In “Hair Is A Covering,” I discussed at length the key words Paul uses in these passages. Earlier in the passage, Paul uses katakaluptó which means “to cover” and the closely related akatakaluptos which means “to uncover.” But here he uses a different word peribolaion which means “mantle.”

Paul was a Pharisee with intimate knowledge of the Hebrew scriptures in the Greek translation. The Old Testament has many words for covering, so let’s look for a contextual explanation there. The Greek Septuagint does include the word peribolaion that is used in this verse. As a verb it refers to getting fully dressed and as a noun refers to a mantle or the collective articles of clothing being worn. Here are some examples (in bold):

You are to take the garments and clothe Aaron with the tunic, the robe of the ephod, the ephod, and the breastplate. Then you are to fasten the ephod on him by its skillfully woven waistband and set the turban on his head and put the holy crown on the turban. Then you are to take the anointing oil and pour it on his head and anoint him.

He put the tunic on Aaron, tied the sash around him, clothed him with the robe and put the ephod on him. He also fastened the ephod with a decorative waistband, which he tied around him.

On the third day Esther put on her royal robes and stood in the inner court of the palace, in front of the king’s hall. The king was sitting on his royal throne in the hall, facing the entrance.

The Lord reigns, he is robed in majesty; the Lord is robed in majesty and armed with strength; indeed, the world is established, firm and secure.

When Elijah heard it, he pulled his cloak over his face and went out and stood at the mouth of the cave. Then a voice said to him, “What are you doing here, Elijah?”

18 In that day the Lord will snatch away their finery: the bangles and headbands and crescent necklaces, 19 the earrings and bracelets and veils, 20 the headdresses and anklets and sashes, the perfume bottles and charms, 21 the signet rings and nose rings, 22 the fine robes and the capes and cloaks, the purses 23 and mirrors, and the linen garments and tiaras and shawls.

When used as a verb (most uses) these refer to wrapping one’s self up (e.g. getting dressed). The final example is a noun use, and it isn’t translated as “a covering.” This is especially notable because here when the LXX uses this word, it doesn’t correspond to a veil in the Hebrew. It refers more accurately to a mantle, cloak, robe, or cape, something worn over the whole body.

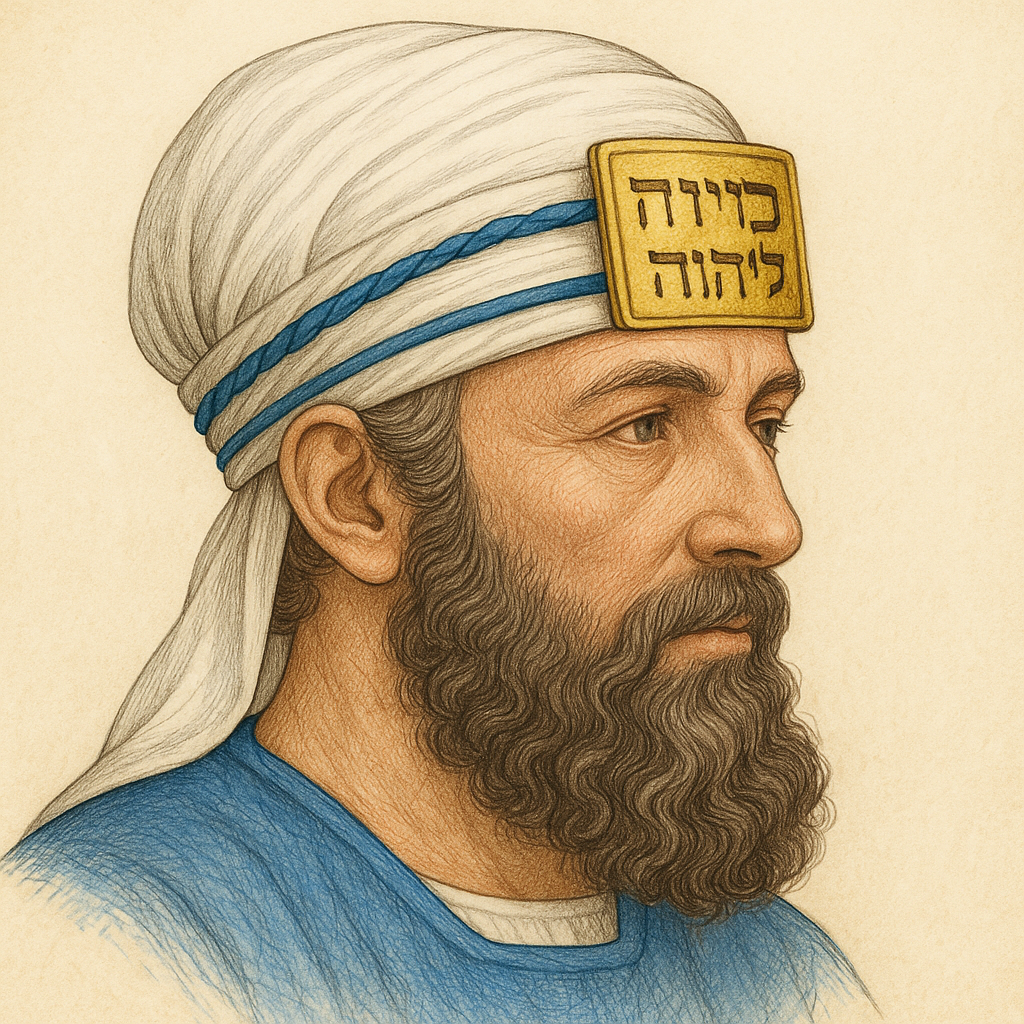

The reference to Aaron above (in Exodus 29:5-7) is especially notable because of what is said just a few verses earlier:

These are the garments they are to make: a breastpiece, an ephod, a robe, a woven tunic, a turban and a sash. They are to make these sacred garments for your brother Aaron and his sons, so they may serve me as priests.

Make a plate of pure gold and engrave on it as on a seal: holy to the Lord. Fasten a blue cord to it to attach it to the turban; it is to be on the front of the turban. It will be on Aaron’s forehead, and he will bear the guilt involved in the sacred gifts the Israelites consecrate, whatever their gifts may be. It will be on Aaron’s forehead continually so that they will be acceptable to the Lord.

The word used here for the head covering is not the same as the word used of the mantle in either the Masoretic Hebrew, the Septuagint Greek, or Paul’s use of the word. Aaron’s head covering by itself was not associated with the word for mantle. In fact, the hat or turban was placed on his head after he was “mantled.” The mantle and the hat (or turban) are distinct garments.

While a hat always covers the head when worn, the mantle was a body cover which may or may not have covered the head when worn. If a woman in Corinth wanted to completely cover, she could wrap her mantle—called a palla—around herself like this:

But the point is simple: her cloth mantle was not a hat. Unlike a hat, a woman could choose not to drape her mantle over her head, but to leave it at her shoulder. It could be drawn over the head, but it was optional, rather than being an inherent and necessary function of her garments.

Despite the English translations to the contrary, the word Paul used in this verse was not the typical word for ‘veil’ (kalumma) or even the word to cover (katakalyptō) that Paul used earlier, rather it was ‘mantle,’ and the word ‘mantle’ did not imply headgear.

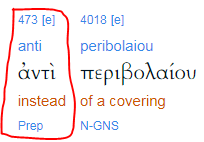

Now, the exact phrase Paul used was “hē komē anti peribolaiou dedotai.” That preposition anti strongly implies substitution, rather than a comparison or addition.

Taking these two points together yields this more literal translation:

…for her hair is given her instead of a mantle

In other words, her long hair is—a mantle—for her head. It substitutes for an actual cloth mantle. (And, notably, each women does not need more than one mantle at a time.)

There is very little ambiguity here. Paul is saying that a woman’s long hair is a mantle. A mantle—such as the palla—fully functioned as a head covering, but a woman had a choice as to whether or not to use it that way. If she chose not to, her hair still functioned as a mantle for her head instead of a cloth head covering. Rather than mandating a separate veil, Paul is emphasizing the symbolic function of hair as a sufficient substitution for a literal cloth covering.

But if any man seems to be contentious, we have no such custom, nor do the churches of God.

If anyone—be they man or woman—disagrees with Paul on this, they should stop being contentious. Paul didn’t just tell the women to stop being contentious, he told the men too.

Nowhere in Paul’s writing did he ever tell men (or husbands) to control women (or their wives). When Paul wanted to correct behavior or give advice, he addressed it directly. If he wanted to instruct women specifically, he explicitly addressed women (e.g. Ephesians 5; 1 Corinthians 14; 1 Timothy 2; Titus 2). Even the pro-head covering position on 1 Corinthians 11:10 states that women were responsible for the “symbol of” authority on their head (i.e. a cloth head covering), because Paul consistently told women to take agency for their own actions. Thus, it makes no sense for Paul to tell the men not to be contentious if the women were the contentious ones who needed to fix the problem.

Note the inherent contradiction in the pro-head covering position. If a woman really had “a symbol of” authority on her head and her control was over this symbol, then the contentiousness would be entirely the result of females choosing wrong. But Paul addresses this to both men and women. There was something the men were doing that needed correction too.[1] This implies that the contentiousness surrounded the debate over covering, not the covering itself. This verse suggests, by implication, that Paul was actually disagreeing with the men in Corinth, not merely instructing contentious women on what they must do.

There exists no evidence of any apostolic custom of head coverings in any of the other churches of God—it is completely absent from any other New Testament writings. Female head covering—excluding, separately, veils that fully cover the face—is also almost completely missing from the Old Testament. Even in Genesis 38:14-15, one of the few references to female veiling, the unmarried, now widowed Tamar had been unveiled. We know that in the early church widows did not veil.

Throughout history female slaves have been forbidden to veil, either by law or other social or cultural conventions. This included the ancient Assyrians, the Romans, and parts of Islamic society. Veiling was often considered a privilege of the social elite. Paul is not trying to create contentious social and cultural upheaval by instituting a standardized policy on veiling, bypassed established conventions. Thus, Paul says that there was no custom regarding being contentious about cloth head coverings in the churches of God.

Paul is putting a stop to the debate, and he does so immediately after he says that hair is given instead of a mantle. The Corinthians are forbidden from trying to create a new doctrine of covering. Ironically, those who promote head coverings are using Paul’s words to keep the Corinthian debate going, long after Paul used those words to settle it.

Footnotes

[1] One might be tempted to think that Paul was addressing men with long hair, but Paul himself grew his hair out while he was in Corinth for 18 months, due to a Nazarite vow he took.

Wasting your intellect and time Derek.

The people you are trying to convince also believe there is a difference between sex and fornication (okay when they do it, not when women or other men do it). The Word also says that a women in her time of the month needs to be separated outside the household. None of these men with their wives or when they were married or “living in sin” made their wife move outside to the in-law house or to a tent in the backyard. Nor their daughters.

This incessant hairsplitting down the line forgets Jesus and why He was sent.

To fulfill the promise

His expectations are yes….indeed high…….He is the most high and we should strive to please Him like a child does to a parent

However, not once did he address a woman and say “Ummm, cover your head before you speak to me” and in fact, a wicked woman washed His feet with her tears and hair.

Relationships, a heart change….and a different mindset He came to promise. Radical indeed.

As for Paul. If he showed up at ANY modern church in the USA today…..even the “devout” ones in Banson, MS or East Bumbledon, ID he would be run out quickly for his unorthodox style of worship, escorted out for “disrupting” the service and laughed at, made fun of.

Modern Manosphere Christians like to talk “provision” and “rules” and “red pill lense” and “maxims” and “Laws of Masculinity” and forget about the hiumble carpenter Himself. Who came to save the world. Not condemn it.

These men still wonder why “the men” dont want to come. They shut out 90% of them

It’s a part of my heritage, including my ethnicity, so it is relevant to me on a more personal level compared to the topics I normally write about. I speak of what I know. While others often speak from a level of pure theory, my views are more practical and hands-on. Few men in the Manosphere have lived in both worlds.

I don’t actually expect to convince anyone, nor am I really trying. I merely hope to be informative. I’m more interested in informing those who might be observing it from the outside who desire an insider’s perspective.

Think about it from the Manosphere’s perspective. They could only dream of acquiring a wife who veils, but have no real chance of this ever happening. Then there is me. I, presumably, could have chosen to find someone like that, but I explicitly chose to reject the “fairy tale marriage” by choosing something else. I doubt they can even comprehend why someone would not want such a “dream scenario.”

There is one other purpose, which will be made clear on Friday. Many head covering proponents believe that their view is so obvious and unambiguous (lol!) that men and women like me are being dishonest, rebellious, stupid, and other such uncharitable descriptions. I am showing that this is disingenuous and that they should…cover their head in shame. But, more importantly, I’m showing that people who do not practice veiling are not doing anything wrong. They should feel no guilt. The doctrine of head covering is largely based on fabrications.

I sincerely appreciate both of your comments on this subject that make this exact point. You cut to the heart of the matter. I will make this point, in my own way, in part 5 on Friday.