I’ve been following along with Ed Hurst’s review of “Hebrew Thought Compared with Greek” by Thorleif Boman (HTCG). I’ve been enjoying the analysis immensely.

My last post was on “HTCG, Chapter 1, Section C: Non-Being.” Now, regarding Chapter 2, “Section C: The Impression of Things,” Ed Hurst says this:

The whole point is the purpose of the thing made, not some abstract idea regarding its form. Boman takes us back to the disagreement between Greek and Hebrew thinking on this issue. To the Greeks, a cooking pot is the basic idea, the material is a separate matter. To the Hebrew, the material defines how the cooking pot can be used, so that each pot of different materials is a different idea. There is no abstract concept of cooking pot; they need to know what the material was or it has no useful meaning.

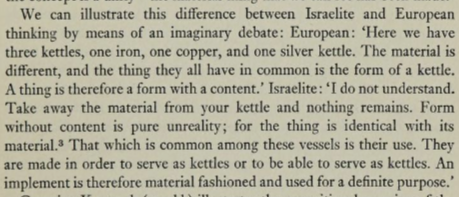

Here is a portion of the passage in Boman’s HTCG to which Hurst is referring:

We can illustrate this difference between Israelite and European thinking by means of an imaginary debate:

European:

Israelite:

Conviction

To the outside observer, it may appear as if my long screeds are attempts to attack someone else’s superior position (out of hate, jealousy, arrogance, or whatever) or to rationalize my own inferior position. It may appear as if I rely on long arguments to draw conclusions and determine my belief. In short, I appear to be a stereotypical Western thinker. It’s just a façade.

When I first read this I immediately intuited that it was wrong. My conviction was immediate and strong. I knew in my heart that what had been written was false. This was not objective, it was intuitive. I didn’t require any logic, evidence, or propositions to understand the spiritual reality.

This is very common. Most of the times when I write someone long and boring on this blog, it was initiated by a strong conviction, a conviction that defies the mind’s description or comprehension.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to convincingly communicate personal conviction to another person who does not share that conviction. For that, you need logic and reason to confirm what is already known. This is often tedious and difficult. All that follows is merely confirmation of the conviction, not the source of my belief.

But make no mistake, spiritual conviction predetermined the outcome.

It’s worth noting that I try never to publish anything that doesn’t have a conviction and a rationally (and biblically) justified conclusion. Being a solid spiritual conviction is not enough to merit publication. I’ve also sat on posts for years waiting to receive a conviction to publish or delete.

What do you think about this non-objective, heart-led mode of understanding. Let me know in the comments.

Introduction

The quotes I presented are an example describing the supposed inherent differences between Hebrew and Greek thought. Let’s look into the claim and see if it has merit.

While we do this mundane experiment, keep in mind that this is not some weird sidetrack. Radix Fidem teaches that these are inherent metaphysical differences between the masses of people in the West and the East that have a direct and consequential bearing on one’s Covenantal relationship with Christ. It has a significant real world impact. It’s entirely possible that men have chosen to embrace (or reject) mysticism based on such a metaphysical premise, a premise which we can actually subject to verification.

Form and Function

Let’s start by considering how English has many different words for cooking equipment: pot, pan, kettle, cauldron, crock, (dutch) oven, skillet, stewpot, stockpot, pyrex (both kinds), earthenware, stoneware, glassware, etc. These vary in form and function. They incorporate both the abstract and the concrete.

In English, sometimes only the material is important, sometimes only the abstract idea is, and sometimes it is both. The binary distinction simply does not apply in English: we understand the basic idea of the pot and we understand how the material of a pot defines how it is used, especially if we prefix the noun with an adjective or two.

For example, the term “cauldron” refers to form (the size, shape, and cast iron material), function (it is used for cooking over an open fire; it has a lid and handles), and moral reality (it is preferred by witches). In involves both the abstract notion of what a pot is alongside the concrete specifics of a pot necessary to give it a useful meaning. The single word carries the (supposed) Hebrew and (supposed) Greek senses.

For example, if we talk of a cast iron dutch oven, we know it is usable over a high temperature fire. But if we talk about an enameled dutch oven, we know it can only be used in a modern temperature controlled oven or stove. As with the (supposed) Hebrew mode-of-understanding, the material alone determines its useful function. You can verify this by going to Amazon and searching for “dutch oven.” Even though this is a Western society, every single listing includes the pot’s material (cast iron, aluminum, or steel) and whether or not it is enameled: the material determines its function.

The English speaker has no difficulty understanding either mode of understanding, whether together or in isolation. But maybe Greek and Hebrew thinkers really were more restricted in thought by their language than we are in English. Maybe the Greek’s and Hebrew’s minds were inflexible as Boman implies. Let’s see.

Hebrew Pots and Pans

Let’s start with a few interesting passages.

Now the rule of the priests with the people was that when anyone sacrificed a sacrifice, while the flesh was boiling, the priest’s servant came with a fork of three teeth in his hand, and he would thrust it into the basin [kiyyor], or kettle [dud], or caldron [qallachath], or pot [parur]. All that the fork brought up the priest would take for himself. This is what they did at Shiloh to all the Israelites who came there. Also, before they burned the fat into smoke, the priest’s servant came and said to the man who sacrificed, “Give meat to roast for the priest, for he will not accept boiled meat from you, but only raw.”

As with English, Hebrew has a lot of words for cookware. I selected these passages because they contain the greatest number of words for pots in the fewest verses, which makes it easier to analyze them together. But other terms include griddle [machabath], pan [masreth], pan [kaph], saucepan [marchesheth], pot [merqachah]. There are also words for non-cooking containers—jars and jugs, melting pot (or furnace) and refining pot (or crucible), and the ink pot—but we will not concern ourselves with those.

Notice how these passages lump a variety of different kinds of cookware together. If Boman and Hurst are correct that you can’t converge the Greek and Hebrew, then the reason the writers did this is because each of these different words for pots represents a different material that determines its use. Similarly, if they are correct, then if, for example, we were to look at the Greek Septuagint, we should see that the Greek words used as translations for the Hebrew use words that describe the abstract concept of the pot, not its form (e.g. material).

What do you think we will find? Will we find that the Hebrew words discuss the material and the Greek works discuss the form and abstract concept? Let’s find out.

What we notice first is that even though a variety of words for pots and pans are used, the context is merely of boiling the meat of the sacrifices. Given the proposed thesis, it seems rather odd that pots made of different materials would all have the same use: boiling sacrificial meat. But it gets even stranger: the material of each piece of cookware is not even mentioned in either verse. If the material was what was important to the Hebrews…

…and not the abstract concept (or category) of a pot…

…then the material must either be implied by context (e.g. what is being cooked) or else incorporated into the word itself.

Regarding context, let’s suppose that the six different cookware mentioned were made of six different materials. Let’s also suppose that the reader would have immediately understood what these six different pots were without it needing to be stated in any way, simply because of his intimate familiarity with how sacrifices were performed. In other words, the reason six different words were used was because six pots made of different materials were used in these sacrifices.

Do you see the problem? The context is not dependent on the material of the pots. Let’s take out references to the materials and restate:

Regarding context, let’s suppose that six different abstract concepts of cookware are mentioned. Let’s also suppose that the reader would have immediately understood what these six types of cookware were without it needing to be stated in any way, simply because of his intimate familiarity with how sacrifices were performed. In other words, the reason six different words were used was because six types of cookware were used in these sacrifices.

You could also rephrase this by saying six different instances of one concept (rather than six) and the point would be the same.

The notion that the pots differ in material is not sustainable on this context. If there is a specific pot for boiling one kind of sacrifice and a different pot for boiling a different kind of sacrifice, then there must be different abstract concepts (or categories) of pots that are independent of their material: different pots for different purposes defined not by their material, but by their function.

Alternatively, consider, hypothetically, that they had six materially identical pots, but each pot was reserved for a different kind of sacrifice.

All of this is truly like trying to strain out gnats. It seems clear from the context that the material of the pots is completely irrelevant. Seemingly, the only reason for the list of pots and pans is that they are all in the category—or abstract concept—of items used for boiling meat.

The most straightforward explanation of the text is that the pots are interchangeable: the sacrifice could be—and probably was—cooked using any of the pots regardless of their material. The material was not useful to consider!

In other words, the Hebrews used the abstract concept of a cooking pot as a cooking pot.

Robert Alter, Hebrew scholar from Berkeley, essentially confirms everything we have said above:

14. the cauldron or the pot or the vat or the kettle. This catalogue of implements is quite untypical of biblical narrative (in fact the precise identification of the sundry cooking receptacles is unsure). The unusual specification serves a satiric purpose: Eli’s sons are represented in a kind of frenzy of gluttony poking their three-pronged forks into every imaginable sort of pot and pan. This sense is then heightened in the aggressiveness of the dialogue that follows, in which Eli’s sons insist on snatching the meat uncooked from the worshippers, not allow them, as was customary, first to burn way the fat.

First, recall how we said “the material must [be]…incorporated into the word itself.” Alter lets us know that “the precise identification of these cooking receptacles is unsure.” This means no one knows if the material of the pots is identifiable based merely on the type of pot. Such an assurance has been lost to history. Even if this was known to the ancient Hebrew, we have no way to know for sure that the differences pertained to material. That claim is, at best, speculation, and at worst completely wrong.

Second, above we concluded that the context does not support the idea that Hebrews understood the usefulness of pots and pans by their material. Alter confirms this when he notes that the context is that Eli and his sons did not care what the pots and pans were, only what the pots and pans were for: containers for boiling meat. The specific identification of the pots and pans—including the material—was not important.

Third, the very purpose of this passage is that the cookware is merely cookware. Neither the meanings of the word nor the context imply any reference to the material of the cookware. The whole point of the context is to reference cookware without respect to its use. That’s an abstract conceptual usage!

To speak of “every imaginable sort of pot and pan,” one must have the general, abstract concept of a pot and pan. Considering that this verse does not contain every Hebrew word for cookware, this must be a multiple-parts-for-the-whole-concept figure of speech.

Fourth, this is an unusual, atypical usage.

Why does this matter? Because “Greek vs Hebrew” thesis is full of selection bias. Most of the time the scriptures are written a certain way, but as this passage shows, traditions do not constitute rules. Just because Greek philosophers and Hebrew prophets wrote a certain way does not mean that the average plow-on-the-ground Hebrew didn’t think using abstract concepts. Literary styles are not a good indication of common speech and common thought.

What people write, even in this day and age on the internet, rarely corresponds to how they speak and live in meatspace (e.g. when Jason met Scott in meatspace after years of contentious internet interactions). Moreover, the people who write often tend to communicate much differently than the people who don’t. We can’t infer from (especially non-fiction) writers how most people speak or otherwise use language.

The thesis is essentially based on a view of how the Hebrews and Greeks understood common oral speech by looking at a selection of written speech. This risks turning the thesis into pure foolishness. Considering the high rates of illiteracy, written speech reflects a nearly insignificant proportion of total Hebrew speech.

What these two passages do prove is the Hebrew ability to use and understand abstract concepts. They prove that there was an abstract concept of a cooking pot and the literary way to show that was by using a flood of related words for pots and pans without providing any context. In other words, the lack of context of normally context-sensitive words is how the abstract concept is expressed grammatically in written form.

If one is looking for an abstract usage of pots and pans, then the meaning of these passages is plain and obvious. If one needs “to know what the material was” in order to find a “useful meaning” in the passage, they are not going to succeed. They won’t understand it.

The use of the abstract concept of cookware serves to change the focus off of the concrete mundane cooking implements onto the intended satire, which itself is an abstract literary device, one of many abstractions used in the Hebrew texts.

In the next section, we will discuss how the Hebrew words used for pots and pans generally refer to their static (or abstract) shape or form, thus revealing that the Hebrews understood their pots and pans by abstract category of their form, rather than their material (or even function).

Greek Pots and Pans

Note: If you are interested in exploring the following topic yourself in more detail, see the Hebrew and Greek interlinear of 2 Chronicles 35:13 and 1 Samuel 2:14.

Recall what we said above:

In my short study of this topic, I did not find what we expected to see. The Greek terms used in the Septuagint sometimes carry the sense of material, sometimes carry the sense of form, and sometimes do both.

Let’s consider 1 Samuel 2:14. The Septuagint seems to use words associated with copper kettles (Greek: lebēta; Hebrew: dud) , brass cauldrons (Greek: chalkíon; Hebrew: qallachath), and earthenware pots or skillets (Greek: chrós; Hebrew: parur). But why do we think that?

In the Hebrew there is an idea that these pots differ in their shape or form. For example, the Hebrew term dud refers both to pot and basket, not because they are made from the same material—they are not—but because they have the same shape. The Hebrew term kiyyor works the same way. It means basin or pot and refers both to the cooking pot and to a basin for washing hands, not because they are made from the same material, but because they have the same shape and because they are generally placed on stands. In like manner, the Hebrew parur carries the sense of being flat (or, possibly, deep): the concern is the visual form, its shape. Similarly, the related words qallachath and tsallachath both carry the sense of deepness: being bowls or bowl-shaped. There is no sense of the material being relevant in any of these Hebrew words. Each Hebrew word is focused on the form of the pot, not its function.

However, once we move to the Greek, the idea that the pots are materially different suddenly emerges.

While the Ancient Greek lebēta does not clearly imply a material, it may be related to the similar sounding word leptos in Koine Greek. That word refers to copper coins. By inference, the Septuagint may be referring to copper kettles. The word chalkíon is less ambiguous and is understood to refer to brass cauldrons. But when we get to chrós, we find that it merely matches the Hebrew’s emphasis on form: both words refer to being flat, as in a skillet. But the story doesn’t end there. In Sirach 13:2, that Greek word is used of earthenware pots. As best as we can tell given the ambiguity that comes from the large number of intervening centuries, in all three cases the material of the pot seems to be relevant in these Greek words. Each Greek word is seems not to be focused on the form of the pot, only its material (and, as with chrós, its function).

Curiously, the materials only show up explicitly in the Greek, not the Hebrew. To wit:

Did you notice that I switched the terms ‘Hebrew’ and ‘Greek’ around (from to the original)? Here is a thought-experiment that highlights the absurdity of the claim:

In the Greek, the idea of a cooking pot as an idea is missing. The material is not a separate matter, but was actually implied by the word itself. For the Greek, the material defined how the cooking pot could be used. There is no abstract concept of a cooking pot in Greek. They needed to know what the material was to understand this verse in the Septuagint.

Based on the evidence presented above, this a sensible explanation of that evidence. Fundamentally, the Greek in the Septuagint shows exactly the opposite of the claim. The Hebrew text describes what Boman and Hurst assign to the Greeks, and the Greek text describes what they assign to the Hebrews. This isn’t just wrong, it’s inverted!

And, just to be clear that this isn’t confirmation bias, I wrote each section of this article as I was researching it. I had written almost the whole section on the Hebrew before I even started looking closely at the Greek equivalents. I didn’t know, going into it, that the evidence would be inverted from the thesis:

I did not know before I started if the Hebrew writers would use non-abstract materials for pots and pans. I did not know before I started if the Greek writers would use abstract concepts. There was always a chance that I would end up confirming part of the thesis. But I didn’t. It was inverted instead!

The takeaway point here is that the thesis relies on the Greek rendering to interpret the Hebrew words with respect to their material, because the Hebrew itself testifies otherwise. In order to support the thesis of the Hebrew and Greek division, one must read the Hebrew scriptures from the Greek perspective. Considering the overall teachings of Radix Fidem, this is, to put it mildly, self-refuting.

Now, I have my doubts as to how confident we can be about any of these translations. We’re talking about words in languages from more than 2,000 years in the past. But the point stands firm: that viewpoint cannot be sustained by the evidence we do have, and the evidence at least appears to directly oppose the view.

Thought Experiment

In light of what we’ve learned, let’s revisit Boman’s thought experiment:

European:

Israelite:

If you are a “race realist” or a “hereditarian,” then you’ll find this example rather quaint, clearly racist, and (because of the irony) a bit funny. What Boman (and, presumably, Hurst) imagine is that the differences between the two parties is one of philosophy, culture, and language, rather than intelligence. The reality is that Boman’s illustration is just an older version of the Breakfast Question Meme.

The whole point of Boman using this illustration is that it is possible for us to understand both perspectives simultaneously. You, Dear Reader, can understand the European philosopher’s and the Israelite philsopher’s “perspectives” equally, and it isn’t because you are steeped in Greek, or Hebrew, or Western, or Eastern thought. You are not confused by either. Indeed, it is rather trivial to understand both perspectives.

But in the illustration, only one of them has a race of people that says:

This illustration does not portray Israelites as some sort of superior spiritual mystic, but as intellectual idiots who are not intelligent enough to think in basic abstractions. Just because the Israelites had a preferred way of thinking and writing didn’t mean they were buffoons who couldn’t understand abstract categorization. Because that’s what Boman is literally saying: that the Israelites did not understand Greek categorization.

What the pots and pans of the Old Testament show is that they very clearly did understand such categorization, even if they preferred to speak of things in other terms. But, a preference is not an ability.

This illustration is an example of the logical fallacy known as a “false dichotomy.”

The Hebrews—like Eve in the Garden—were quite capable of abstract counterfactual reasoning, just like anyone else with a sufficient level of intelligence. Abstract thinking wasn’t invented, let alone invented by the Greeks. The fact of the matter is that Israelites had no problem understanding the concept of the form of a kettle separately from its material makeup.

This is demonstrated at least twice in scripture with respect to pots and pans. I didn’t even bother to find more examples, but I’d guess there are others, perhaps even a majority. The fact that I didn’t even have to do a complete word study to find key counterexamples should tell you something about the supposed unanimity of the binary Hebrew vs Greek experience. If you recall, I did something similar regarding one commenter’s claim that the early church fathers are unanimous regarding women not being made in the image of God. Hardly trying, I found two counterexamples. Then, over a few months, I found more counterexamples without trying, until his view turned out to be, at best, a minority attestation.

In summary…

…we find that both of these are demonstrated to be incorrect, even inverted. Moreover, we find that it applies more closely to the Greek way of thinking than the Hebrew.

The fact that I didn’t even have to do a complete word study to find key counterexamples should tell you something about the supposed unanimity of the binary Hebrew vs Greek experience.

That reminds me of Charton’s latest post(about how the left and right have the same ”values”).

Tuesday 17 September 2024

Values Consumerism is evil

Tools of Satan?

The point at which I recognized “the beginning of the end” for genuine and nature-rooted “environmentalism” was when “Green Consumerism” emerged in the later 1980s – a concept that now dominates the Green Movement almost to the point of monopoly.

The idea was that Green values would be promoted by properly-directed expenditure of Green consumers, by their buying choices.

This replaced the earlier idea that those who aimed to preserve the natural world should reduce their consumption…

Half a century ago an archetypal environmentalist tried to be self sufficient by living as a modern peasant on “three acres and a cow”; nowadays he works as a sustainability bureaucrat – and inhabits a solar-panelled mansion with a hybrid and a electric car for each member of the family.

Since the late 80s there has been a vast proliferation of “consumer guides”, further shaped by totalitarian regulations; that advise and direct people on how to spend their money such as to support sustainability, diversity, feminism, or whatever totalitarian Leftist agenda item most takes your fancy…

And these are mirrored – in a much smaller way- among those who purport to oppose Leftism (on the “Right”), and even among those who purport to support Christian values.

The current world (including the blogosphere!) is therefore replete with advice and instructions about which companies and products we “ought” to choose, and which we ought to avoid.

This is very popular because, apparently, nearly everybody seems to enjoy moralistically advising other people what they should and shouldn’t do with respect to their own particular hobby horse.

…Especially while pretending that this is all morally highly-significant, and that the adviser’s own lifestyle preferences are objective evidence of moral superiority.

So public discourse is full of stuff about the need either to-buy, or to-boycott, this – or that.

In the UK, we have seen the ultimate reductio ad absurdum of training young children in schools to regard the issue of plastic drinking straw usage as a major issue of values; and to celebrate the “banning” of such instruments-of-the-devil as a triumph of environmental protection.

This consumerist moral perspective is grossly inadequate as a life-goal; because it necessarily supports the existing system in a deep and qualitative way; while pretending to influence it by living in accordance with superficial, quantitative differences: supposed distinctions that are often too small, too temporary, and too uncertain to have even the potential to make a significant positive difference.

Indeed; this perspective is worse than inadequate, worse than useless: it is a profoundly harmful way of living – because it is strategically stupid and deliberately dishonest.

And not by accident.

The fact that Values Consumerism emerged when it did, and that it is supported by the globalist totalitarians (Western and International politics, Big Media, Big Finance, Big Corporations etc.); demonstrates that it is Values Consumerism which is literally and without exaggeration a tool of Satan, an instrument of the Devil…

Bruce is right!-I remember all the ”buy partially recycled Comic books to save Mother Earth” marketing from Archie Comics (mainly through their version of the TMNT between ’88 &’92 )Then republicans jumped on board by buying Elushbo’s books(then ties) in the 1990s to save America! (which obviously failed as WE must save it still today!)

The difference between the left and right is largely one of magnitude, not philosophy.

Pingback: Reviewing "Hellenism Is From Hell" (Part 2)

Pingback: Christian Mysticism and Reason - Derek L. Ramsey

Pingback: Hebrew Abstraction - Derek L. Ramsey