The New Sacrifice

In the midst of my series on the Eucharist, I discussed the prophecy of Malachi and concluded that what God wanted most was followers who love him:

This is why the greatest commandment is “Love the Lord your God.” The fulfillment of Malachi meant that no longer were sacrifices required for sin, for Christ was the final sacrifice. Now the only sacrifice was the circumcision of the heart: to love God freely and fully, to offer him one’s joyful praise and thanksgiving.

Citation: Derek L. Ramsey, “The Eucharist, Part 24: Cyril of Jerusalem.”

Cyril had identified the incense and pure sacrifice spoken of by Malachi as the blessings, praise, and glory that the church—congregation—offers to God. The new followers of God would be motivated, not by the commandments found in the law, but by their love for God through his Son Jesus. The new model would be one of relationship governed by love.

The essence, then, of the new sacrifice of thanksgiving—the eucharist—was one of love: showing gratitude, praise, thanks, service, and gifts through a pure heart and mind, that is, out of love for God. But this sacred secret underlying the prophecy of Malachi would be veiled from mankind until Jesus himself revealed it.

The same day that I wrote the above, Bruce Charlton explained how Jesus revealed the purpose of love in the fourth gospel:

…

Love is mentioned many, many times; and seems like the core term – a new and all-transcending principle of life – the new reality that Jesus made-happen. Reading this, one is immediately compelled to ponder this astonishing reality that Jesus has placed at the heart of creation. The Holy Ghost, the Comforter, is described Jesus himself (not a separate person) after he will have ascended to Heaven – and who will be present to all who love and follow Jesus. The Holy Ghost is stated to provide – in a personal way – all that is required of guidance and knowledge. This is emphasized: everything the disciples need to know after Jesus has ascended to Heaven, will be provided by the Holy Ghost.

Citation: Bruce Charlton, “What Does Jesus Teach in the Fourth Gospel.” (2024)

Given that I’ve entitled this series “Justification by Faith,” what does this discussion on love have to do with it? Well, it turns out that love has everything to do with it.

Let’s go back to 2020, when I had a series of discussions on Timothy F. Kauffman’s blog Out of His Mouth (which I will now adapt into a series here). There I had a few months of conversations with a few Roman Catholics in the comment sections here and here. We discussed justification by faith. How did I begin it? With a discussion of love.

The Primacy of Love

Why is love the Greatest Commandment? If we are saved by faith, why isn’t faith the Greatest Commandment? If love is just another work as some have claimed, shouldn’t faith—which comes before all works—be greater than love?

Yet, time and again, scripture says that love, not faith, is the greater. Love is greater than faith for the simple reason that love is prior to faith. One cannot have faith without love, just as faith is prior to works (i.e. obedience).

This is surprisingly trivial to demonstrate! God is love, but God is not faith. God sent Jesus because he is love, and therefore faith is the consequence of—dependent on—that love. So if faith is the prerequisite for salvation, and love a prerequisite for faith, then love is a prerequisite for salvation. But of course it is:

Works (i.e. obedience) accompany faith, but salvation is only dependent on faith. Similarly, love accompanies faith and obedience, but as shown above, this does not imply equivalence. Love is greatest, because God is love (1 John 4:8), faith follows from love (John 3:16), and obedience from faith (James 2:18).

Yet, having read John 3:16, one might reasonably ask:

…and…

To this I ask:

Can a believer have belief[1] without love?

Can a believer have works[2] without belief?

The answer to both is “No.”

Faith—and salvation—does not come from obedience, nor does love come from faith. (Already existing) faith is demonstrated by obedience (James 2:18) and one’s belief—one’s faith (as we’ll see in Part 2, faith is belief)—is demonstrated through one’s love. It is love—not faith and not works—that identifies who Christ’s disciples are.

How can you tell if a person puts their trust—faith; belief—in Christ as his disciple? How can you tell if a person’s deeds—their fruit—come from God? By their love.

How are Christ’s followers identified? Is it by their works? No! Is it by their faith, what they say the believe? No! It is by their love.

Notice that this a new commandment, not a commandment of the Law of Moses (e.g. Leviticus 19:18)! There is something qualitatively different about the love that Christ commanded:

Of course a believer can merely have faith, but if he does not have love, that faith is meaningless. Such faith cannot save, for it is without love. It is the nature of that faith that matters, in the context of both love and works. The demons believe (James 2:19), but the nature of their belief does not save them. Faith alone saves, but not all faith saves.

So, yes, it is possible to speak of faith without salvation and without the believer’s love, but there is no reason to do so. It simply isn’t relevant.

The Bible only once mentions “faith alone,” and it is not where you’d expect it to be:

Don’t worry, we will discuss the meaning of this verse later in the series.[3] Suffice it to say, for now, that when the Bible was given the opportunity to say “you are saved by faith alone,” it never did so. Why not?

The reason is plain: you cannot be saved by faith without love.

So what do we mean when we say “a man is saved by faith alone?” We merely mean that “a man is saved by faith alone without works.”

Throughout the rest of this series, we will take for granted that saving faith requires love, because it does. One’s faith must be rooted in love, or else it is meaningless. But, we are not going to say “a man is saved by faith alone plus love” (as Jeremy Akin did). The Bible never felt the need to say such a thing, and neither do we. Faith in Christ necessarily requires and implies love, but that is not, of itself, a description of justification or salvation.

People will stumble over things like “the demons have faith” (James 2:19) without considering what they have faith in. The demons do not love God. Their faith is in their steadfast knowledge, trust, and confidence that there is a one God who will faithfully do precisely what he said he will do. Their faith is without any blindness or doubt: what God has promised them will come to pass. It is completely assured. But their faith is not informed by love: it will not save them. You, who are saved, must have a faith that is informed by your love of God (and your neighbor).

When it comes to faith, it is the nature of the heart that matters. God wants followers who love him, not ones who merely do the law by rote. The state of your heart is what determines whether or not your faith (and works!) are real. Love is a qualitatively different ‘commandment’ from faith and works, which is why to love is the greatest commandment. You cannot turn to God in faith in Christ without God having first turned your heart towards him in love.

The greatest commandment is described within the Law itself:

Which Jesus quoted as:

You must love God with your entire being. This is what is meant by the mind, the Hebrew idiom ‘heart’, and by the word ‘soul’:

Citation: Robert Alter, “The Hebrew Bible: The Five Books of Moses.”, p. 641.

Without this love you cannot have faith in Christ. Faith cannot be parceled out in chunks or stages. It isn’t partial nor a development over time. Thus, love must encompass the entirety of your being at the time of your conversion.

Love is personal. It requires a being. A relationship—as with God, a personal being—is not a work. It is a commandment within the Law, the foundation under which the Law is given, but it is not a work of the Law. Love is the very reason for the Law. Love is prior to the Law, for the same reason that God himself is prior to the Law. Love is the nature of God, and it is expressed in the covenantal personal relationship between God and man through Christ Jesus, sealed with his blood.

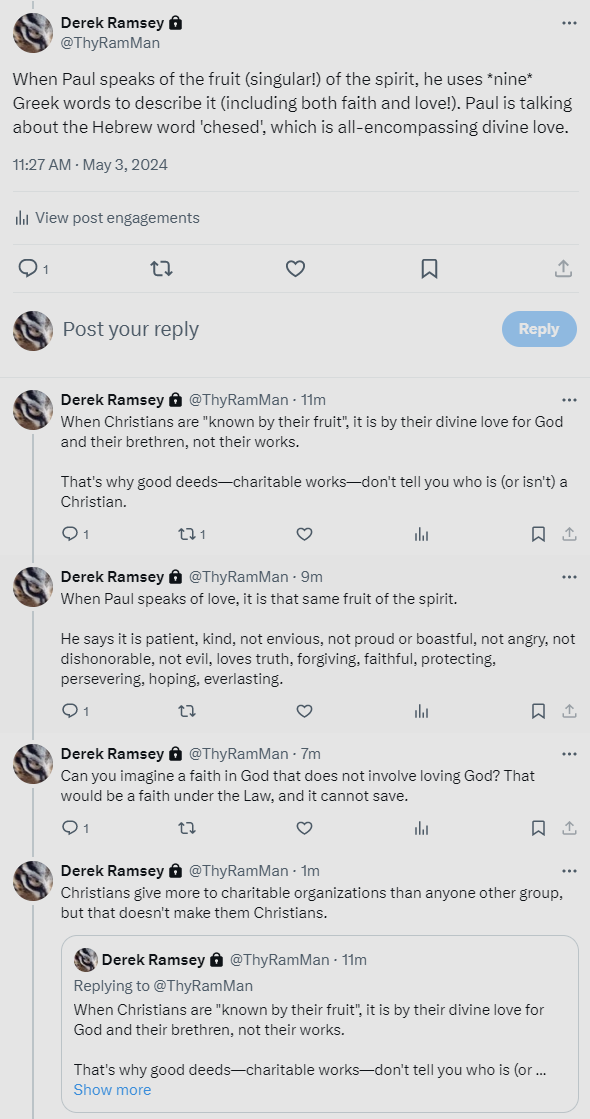

The word ‘mercy’ is the Hebrew chesed (see this commentary), which is same as the fruit (singular!) of the spirit. Paul needs to use nine Greek words to describe the Hebrew concept: love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control! Notice that the fruit of the spirit includes both faith and love. Notice also that what is desired—faith (i.e. knowledge of God) and love (i.e. mercy)—is contrasted specifically against what is not desired—doing (i.e. sacrifice).

Hosea 6:6 could be paraphrased as “I want faith in God and steadfast love with the entirety of your being.”

See also: Isaiah 55:1-4, Acts 13:34-37, and Romans 12:1.

Paul said that if I have a faith (that is, belief) that does—even to moving mountains—but have no love, I am nothing. A faith without love, even one full of good works, is nothing.

Where does faith come from? It comes from God, who is love. God is love. Without love, you cannot know God, for God is love. To have faith in God—to know him as a being—requires a covenant relationship of love (chesed). You cannot have faith without it. This is why God, in Hosea, speaks both of faith and love. It is why Isaiah speaks of the covenant within the context of both belief—faith—and chesed love:

Eternal life in a personal covenant relationship with God is inextricably linked with both love and belief. By contrast, eternal life is explicitly not based on works of the law.

Do you truly love God? Do you actually want what God has to offer you? Why do you believe?

People whose faith—and their conception of salvation—is primarily rooted in following rules, rituals, sacraments, covenants, and doing good works are like the Jews spoken of in Malachi’s prophecy. Their defiled sacrifices do not please God. God wants new followers whose hearts are pure: those who love him for who he is with their whole being. If your faith is rooted in obedience to regulations and authority, and not rooted in love, then you’ve missed the mark. Whether or not you think that “salvation is by faith alone” or “salvation is by faith and works” isn’t a relevant distinction for you.

Without love, faith does not matter.

Faith does not precede love.

Works do not precede justification.[4]

Love is prior to faith. Love is prior to works. You must have love. It is the greatest commandment.

You have a choice to put your faith in the Law of Moses or to put your faith in the love of God through Christ. Only one can save, and it always involves love.

If you do not or can not understand any of this, read the fourth gospel. Jesus explains it there.

For another approachable explanation of “justification of faith” using very different words, see Timothy Kauffman’s “The Blonde Kids Are On Our Ticket.” It is perhaps the best explanation of “Justification by Faith” that I have ever read. You might well agree. If that kind of explanation works for you, you don’t need to continue reading my series.

NOTE: Kauffman thinks love is another kind of work. I cordially disagree.[5]

Footnotes

[1] Belief—faith and trust—that leads to salvation. This might be termed ‘true belief’ or ‘living faith’ to distinguish it from ‘dead faith.’

[2] Works: obedience to God.

[3] Hint: James is speaking of justification before men, not justification by God.

[4] For Augustine, “being justified” means being made righteous by God:

Now he could not mean to contradict himself in saying, “The doers of the law shall be justified,” as if their justification came through their works, and not through grace; since he declares that a man is justified freely by His grace without the works of the law, intending by the term “freely” nothing else than that works do not precede justification. For in another passage he expressly says, “If by grace, then is it no more of works; otherwise grace is no longer grace.” But the statement that “the doers of the law shall be justified” must be so understood, as that we may know that they are not otherwise doers of the law, unless they be justified, so that justification does not subsequently accrue to them as doers of the law, but justification precedes them as doers of the law. For what else does the phrase “being justified” signify than being made righteous,—by Him, of course, who justifies the ungodly man, that he may become a godly one instead?

Citation: Augustine of Hippo, “Treatise on the Spirit and the Letter.” Chapter 45. Edited by Philip Schaff.

[5] During the debate between James White and Jimmy Akin (just after 1:11:00 in the second debate), during the Akin’s interrogation of White, White acknowledges that saving faith includes love. He also acknowledges that faith alone is true if it is formed faith working through love as long as the Roman Catholic sacramental and priestly assumptions are not included.

The crux of the issue is this:

The Roman Catholic takes this to mean:

But Kauffman’s objection is just an argument from consequences. The Roman Catholic uses this understanding in order to conclude something about the sacramental system, which as we’ve noted in “The Eucharist, Part 40: Conclusion,” is based on a late-4th-century historical anachronism. One does not have to reject the role of love in faith in order to also reject the Roman Catholic innovation. The two concepts are not mutually exclusive.

Consider what John Chrysostom wrote:

Citation: John Chrysostom, “Homily 5 on Galatians.”

Chrysostom is speaking of the Jews who sought to be justified by their own works under the Law (i.e. circumcision). Chrysostom is clearly stating that, had they loved Christ as they should have, they would not have done this. Paul compares faith with love and faith without love by contrasting those who sought the circumcision with those who did not. Those who seek justification without works of the Law are those who have faith with love. Those who seek justification by works of the Law—circumcision—are those who have ‘faith’ without love.

There is nothing objectionable about this. It is completely logical.

Galatians 5:6 isn’t saying that the love makes faith “work.” That makes mincemeat of what Paul was saying. Rather, he’s saying that a lack of love cannot produce faith. Christ told us that if we love him, we will keep his commandments. What are his commands? That we love him and believe in him. Those who seek to be justified under the Law do not believe or love him. How could they, when he told them that what it means to believe and love him is that you are not justified under the Law?

It is just as we’ve seen in numerous scriptures above. God wants followers who love him and have faith in him. He consistently contrasts this with those who perform deeds under the law. Those who seek justification under the law do not love God and do not have faith. Chrysostom is echoing the exact same thing.

Pingback: Justification By Faith

Pingback: Mutual Submission, Part 10